begin quote from:

Cane sugar in the medieval era in the Muslim World and Europe

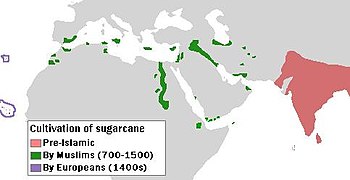

The westward diffusion of sugarcane in pre-Islamic times (shown in red), in the medieval Muslim world (green) and by Europeans in the 15th century (islands circled by violet lines)[14]

During the medieval era, Arab entrepreneurs adopted sugar production techniques from India and expanded the industry. Medieval Arabs in some cases set up large plantations equipped with on-site sugar mills or refineries. The cane sugar plant, which is native to a tropical climate, requires both a lot of water and a lot of heat to thrive. The cultivation of the plant spread throughout the medieval Arab world using artificial irrigation. The Latin-speaking countries imported refined cane sugar from the Arabs beginning in the 12th century. The cane sugar plant was generally not grown in medieval Latin Europe, with small exceptions in southern Italy and southern Spain after the Arabs were ousted from there. The volume of imports increased in the later medieval centuries as indicated by the increasing references to sugar consumption in late medieval Western writings. But cane sugar remained an expensive import. Its price per pound in 14th and 15th century England was about equally as high as imported spices from tropical Asia such as mace (nutmeg), ginger, cloves, and pepper, which had to be transported across the Indian Ocean in that era.[1]

Ponting traces the spread of the cultivation of sugarcane from its introduction into Mesopotamia, then the Levant and the islands of the eastern Mediterranean, especially Cyprus, by the 10th century.[17] He also notes that it spread along the coast of East Africa to reach Zanzibar.[17]

Crusaders brought sugar home with them to Europe after their campaigns in the Holy Land, where they encountered caravans carrying "sweet salt". Early in the 12th century, Venice acquired some villages near Tyre and set up estates to produce sugar for export to Europe, where it supplemented honey as the only other available sweetener.[18] Crusade chronicler William of Tyre, writing in the late 12th century, described sugar as "a most precious product, very necessary for the use and health of mankind".[19] The first record of sugar in English is in the late 13th century.[20]

Ponting recounts the trials of the early European sugar entrepreneurs:

The crucial problem with sugar production was that it was highly labour-intensive in both growing and processing. Because of the huge weight and bulk of the raw cane it was very costly to transport, especially by land, and therefore each estate had to have its own factory. There the cane had to be crushed to extract the juices, which were boiled to concentrate them, in a series of backbreaking and intensive operations lasting many hours. However, once it had been processed and concentrated, the sugar had a very high value for its bulk and could be traded over long distances by ship at a considerable profit. The [European sugar] industry only began on a major scale after the loss of the Levant to a resurgent Islam and the shift of production to Cyprus under a mixture of Crusader aristocrats and Venetian merchants. The local population on Cyprus spent most of their time growing their own food and few would work on the sugar estates. The owners therefore brought in slaves from the Black Sea area (and a few from Africa) to do most of the work. The level of demand and production was low and therefore so was the trade in slaves — no more than about a thousand people a year. It was not much larger when sugar production began in Sicily.During the 1390s, a better press was developed, which doubled the amount of juice that was obtained from the sugarcane and helped to cause the economic expansion of sugar plantations to Andalusia and to the Algarve. It started in Madeira in 1455, using advisers from Sicily and (largely) Genoese capital for the mills. The accessibility of Madeira attracted Genoese and Flemish traders keen to bypass Venetian monopolies. "By 1480 Antwerp had some seventy ships engaged in the Madeira sugar trade, with the refining and distribution concentrated in Antwerp. The 1480's saw sugar production extended to the Canary Islands. By the 1490's Madeira had overtaken Cyprus as a producer of sugar."[21] African slaves also worked in the sugar plantations of the Kingdom of Castile around Valencia.[21]

In the Atlantic ocean [the Canaries, Madeira, and the Cape Verde Islands], once the initial exploitation of the timber and raw materials was over, it rapidly became clear that sugar production would be the most profitable way of getting money from the new territories. The problem was the heavy labour involved because the Europeans refused to work except as supervisors. The solution was to bring in slaves from Africa. The crucial developments in this trade began in the 1440's...[18]

In the 16th century Rabbi Yosef Karo, the author of the Shulchan Aruch, the code of Jewish law, mentions the use of sugar mixed with the juice of lemons and water by Jews in Cairo, Egypt to make lemonade on Sabbath. (Orech Chayim, Hilchot Shabbat)

Sugar cultivation in the New World

The Triangular trade - slaves were imported into the Caribbean Islands to plant and harvest sugar cane.

The approximately 3,000 small sugar mills that were built before 1550 in the New World created an unprecedented demand for cast iron gears, levers, axles and other implements. Specialist trades in mold-making and iron casting developed in Europe due to the expansion of sugar production. Sugar mill construction developed technological skills needed for a nascent industrial revolution in the early 17th century.[22]

After 1625, the Dutch carried sugarcane from South America to the Caribbean islands, where it was grown from Barbados to the Virgin Islands. Contemporaries often compared the worth of sugar with valuable commodities including musk, pearls, and spices. Sugar prices declined slowly as its production became multi-sourced, especially through British colonial policy. Formerly an indulgence of only the rich, the consumption of sugar also became increasingly common among the poor too. Sugar production increased in mainland North American colonies, in Cuba, and in Brazil. The labour force at first included European indentured servants and local Native American slaves. However, European diseases such as smallpox and African ones such as malaria and yellow fever soon reduced the numbers of local Native Americans).[22] Europeans were also very susceptible to malaria and yellow fever, and the supply of indentured servants was limited. African slaves became the dominant source of plantation workers because they were more resistant to malaria and yellow fever, and because the supply of slaves was abundant on the African coast.[23][24]

During the 18th century, sugar became enormously popular. Britain, for example, consumed five times as much sugar in 1770 as in 1710.[25] By 1750 sugar surpassed grain as "the most valuable commodity in European trade — it made up a fifth of all European imports and in the last decades of the century four-fifths of the sugar came from the British and French colonies in the West Indies."[25] The sugar market went through a series of booms. The heightened demand and production of sugar came about to a large extent due to a great change in the eating habits of many Europeans. For example, they began consuming jams, candy, tea, coffee, cocoa, processed foods, and other sweet victuals in much greater numbers. Reacting to this increasing craze, the islands took advantage of the situation and set about producing still more sugar. In fact, they produced up to ninety percent of the sugar that the western Europeans consumed. Some islands proved more successful than others when it came to producing the product. In Barbados and the British Leeward Islands sugar provided 93% and 97% respectively of exports.

Planters later began developing ways to boost production even more. For example, they began using more manure when growing their crops. They also developed more advanced mills and began using better types of sugarcane. In the eighteenth century "the French colonies were the most successful, especially Saint-Domingue, where better irrigation, water-power and machinery, together with concentration on newer types of sugar, increased profits."[25] Despite these and other improvements, the price of sugar reached soaring heights, especially during events such as the revolt against the Dutch[26] and the Napoleonic Wars. Sugar remained in high demand, and the islands' planters knew exactly how to take advantage of the situation.

A 19th-century lithograph by Theodore Bray showing a sugarcane

plantation. On right is "white officer", the European overseer. Slave

workers toil during the harvest. To the left is a flat-bottomed vessel

for cane transportation.

Sugarcane quickly exhausts the soil in which it grows, and planters pressed larger islands with fresher soil into production in the nineteenth century as demand for sugar in Europe continued to increase: "average consumption in Britain rose from four pounds per head in 1700 to eighteen pounds in 1800, thirty-six pounds by 1850 and over one hundred pounds by the twentieth century."[28] In the 19th century Cuba rose to become the richest land in the Caribbean (with sugar as its dominant crop) because it formed the only major island landmass free of mountainous terrain. Instead, nearly three-quarters of its land formed a rolling plain — ideal for planting crops. Cuba also prospered above other islands because Cubans used better methods when harvesting the sugar crops: they adopted modern milling methods such as watermills, enclosed furnaces, steam engines, and vacuum pans. All these technologies increased productivity. Cuba also retained slavery longer than the most of the rest of the Caribbean islands.[29]

After the Haitian Revolution established the independent state of Haiti, sugar production in that country declined and Cuba replaced Saint-Domingue as the world's largest producer.

Long established in Brazil, sugar production spread to other parts of South America, as well as to newer European colonies in Africa and in the Pacific, where it became especially important in Fiji. Mauritius, Natal and Queensland in Australia started growing sugar. The older and newer sugar production areas now tended to use indentured labour rather than slaves, with workers "shipped across the world ... [and] ... held in conditions of near slavery for up to ten years... In the second half of the nineteenth century over 450,000 indentured labourers went from India to the British West Indies, others went to Natal, Mauritius and Fiji (where they became a majority of the population). In Queensland workers from the Pacific islands were moved in. On Hawaii, they came from China and Japan. The Dutch transferred large numbers of people from Java to Surinam."[30] It is said that the sugar plantations would not have thrived without the aid of the African slaves. In Colombia, the planting of sugar started very early on, and entrepreneurs imported many African slaves to cultivate the fields. The industrialization of the Colombian industry started in 1901 with the establishment of Manuelita, the first steam-powered sugar mill in South America, by Latvian Jewish immigrant James Martin Eder.

While no longer grown and processed by slaves, sugar from developing countries has an ongoing association with workers earning minimal wages and living in extreme poverty.[30]

The rise of beet sugar

Sugar refinery in Šurany (Slovakia) founded in 1854 (a picture is from 1900).

- More information in the History section at Sugar beet

Napoleon, cut off from Caribbean imports by a British blockade, and at any rate not wanting to fund British merchants, banned imports of sugar in 1813. The beet sugar industry that emerged in consequence grew, and sugar beet provides approximately 30% of world sugar production.

In the developed countries, the sugar industry relies on machinery, with a low requirement for manpower. A large beet refinery producing around 1,500 tonnes of sugar a day needs a permanent workforce of about 150 for 24-hour production.

No comments:

Post a Comment