(if you haven't seen this movie likely you don't want to read this). We had been discussing manifesting a physical body (and not just soul traveling). So, watching Luke Skywalker manifesting a body to face Ky-loren is an important display of how an actual adept can manifest a body (beyond just soul traveling) for example, like SAI Baba and other masters commonly do. So, the spiritual message of the movie is like the other movies on Star Wars which are based upon the ACTUAL experience of the energy that binds the whole universe together as Luke Teaches Ray about during the movie. Until you understand this Energy that is everywhere that each of us are one with, you cannot really soul travel properly or understand that time and space is temporal and not permanently real. It took me 10 years of soul traveling to realize that I was already everywhere in time and space and that the material universe is ONLY inside of God's mind and doesn't really exist physically except in our perceptions of it.

So, basically the physical universe ONLY exists because we believe it does (and of course God facilitates this as well) to make earth a living experience of higher education for our souls.

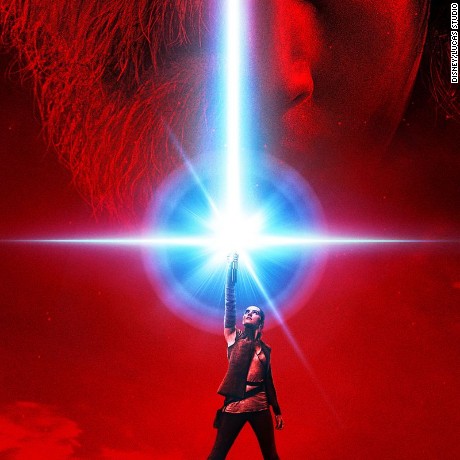

To see video about why George Lucas added spirituality into Star Wars originally click on word button below:

The spiritual message hidden in 'Star Wars'

The spiritual message hidden in 'Star Wars'

(CNN)"Star Wars" has always kept its fingers close to America's spiritual pulse.

In

the '70s and '80s, the interstellar saga explored Eastern traditions,

mainly Buddhism and Taoism, just as many "spiritual, but not religious"

dabblers were doing the same.

At

the turn of the millennium, "Star Wars" caught the McMindfulness craze.

"The Phantom Menace" opens with two Jedis talking about the benefits of

meditation. Riveting, it was not.

But

the latest film in the saga, "Star Wars: The Last Jedi," touches on

trends in American religious life in some surprising ways, especially

for a franchise that's so nakedly commercial. ("The Last Jedi" was the highest-grossing movie in the United States last year and raked in nearly $1.3 billion worldwide.)

"It

is very much a movie of this time," said the Rev. angel Kyodo williams,

a Buddhist teacher, social justice activist and "Star Wars" aficionado

who lives Berkeley, California. "It draws on ancient teachings, as well

as what is happening in this country right now."

But

there's some debate about what "The Last Jedi" intends to say about

modern religious life: Is it warning about the end of organized

religion, or a parable about spiritual renewal?

'Do, or do not. There is no try.'

"Star Wars" is, at heart, a story about the rise and fall of an ancient religion.

When

we meet the Jedis, in Episode I, they're mindfulness-meditating,

axiom-spouting space monks who keep order in the galaxy and swing a

swift lightsaber.

By Episode VIII

-- "The Last Jedi" -- the once-great order is reduced to a lone soul,

Luke Skywalker, serving a self-imposed penance on a remote island.

When Rey, the young heroine, shows up seeking spiritual training, Luke refuses.

The

Jedi religion is over, he says, a victim of its own hypocrisy and

hubris. Luke even prepares to burn the ancient Jedi texts.

(In a bit of historical irony, the island on which the scene is filmed, Skellig Michael, was home to medieval Irish monks who "saved civilization" by rescuing ancient Christian books.)

But

the film hints that Luke might not be the "last Jedi," after all. Even

without his help, Rey is remarkably skilled at connecting with the

Force, the mysterious energy that pervades the galaxy.

This

is where some cultural commentators see an argument against organized

religion. In previous "Star Wars" films, using the Force required

joining the Jedis and spending years learning the "old ways" from

established masters.

Luke seems to say that none of that matters anymore.

"He is making a very modern case for spirituality over organized religion," argues Hannah Long

in The Weekly Standard, a conservative magazine. "If all roads lead to

the Force, then the dusty tradition and doctrine doesn't really matter."

In The Atlantic, Chaim Saiman makes a similar argument.

"The Last Jedi" seems to reflect many millennials' ideas about

religion, namely their waning interest in "structured religion" in favor

of "unbounded spirituality," he writes.

But is that the whole story?

'Always two there are: A master and apprentice'

George

Lucas, the creator of "Star Wars," says he wanted to do more than

entertain the masses. He wanted to introduce young Americans to

spiritual teachings though "new myths" for our globalized, pluralistic

millennium.

"I see 'Star Wars' as

taking all the issues that religion represents and trying to distill

them down into a more modern and accessible construct," Lucas has said.

"I wanted to make it so that young people would begin to ask questions

about the mystery."

In

this, Lucas sounds a lot like his mentor, Joseph Campbell, a scholar

who studied world myths. Campbell argued that all cultures impart their

values to the next generation through archetypal stories. He believed

the same about organized religion, but said it must "catch up" to the

"moral necessities of the here and now."

Lucas

himself has been called a "Buddhist/Methodist," though it's not clear

that he identifies with either religious tradition. "Let's say I'm

spiritual," he told Time magazine in 1999.

Irvin

Kirshner, the director of the "The Empire Strikes Back," says Yoda --

the small but spiritually powerful Jedi master -- was created in part to

evangelize for Buddhism.

"I want

to introduce some Zen here," he said, "because I don't want the kids to

walk away just thinking that everything is a shoot-'em-up."

Mushim

Patricia Ikeda, a Buddhist teacher and social justice activist, said

Yoda reminds her of the monks she studied with in Korea: wise, cryptic

and a little impish.

"I watched those movies and I thought, check, check, double-check," said Ikeda, the community coordinator at the East Bay Meditation Center in Oakland, California.

There's been a lot written about Buddhism in "Star Wars," from scholarly papers to popular books,

so I won't go into too much detail here. Suffice it to say, "Star Wars"

borrows quite a bit from Buddhist symbols, teachings and practices.

One writer calls it "Zen with lightsabers."

The

name of the Jedi Order itself could be borrowed from Asian culture,

said religion scholar Christian Feichtinger. The "jidaigeki," a genre of

popular movies in Japan, depict samurai learning to combine

swordsmanship with spiritual training, and slowly discovering that the

mind is mightier than the sword. (Sound familiar?)

Throughout

"Star Wars," the Jedi talk often about mindfulness and concentration,

attachment and interdependence, all key Buddhist ideas. Two --

mindfulness and concentration -- are steps on the Eightfold Path, the Buddha's guide to spiritual liberation.

You

could argue that "The Last Jedi," telegraphs its spiritual debts to

Buddhism. When Rey is meditating, she touches the ground, mirroring an

iconic image of the "earth-touching" Buddha.

And, as an astute colleague noticed, a mosaic pool a Jedi temple shows an icon that looks a lot like Kannon Boddhisattva, a large-eared Buddhist being who hears the cries of the world.

But

there's more to spirituality in "Star Wars" than Buddhism. Like Zen

itself, the saga blends aspects of Taoism and other religious

traditions. "The Force," for example, sounds a lot like the Taoist idea

of "chi," the subtle stream of energy that animates the world.

And

there's plenty about "Star Wars" that doesn't jibe with Buddhism, not

least the fact that Darth Vader -- the supreme personification of evil

-- is an avid meditator.

Even the storylines that borrow from other religions teach Buddhist lessons.

Take

Darth Vader's narrative. He was born of a virgin, and was supposed to

save the galaxy before he succumbed to temptation, all ideas with clear

Christian resonances.

But the reason for Vader's fall from grace -- the lessons viewers are supposed to take away -- seems distinctly Buddhish.

Anakin Skywalker, the Jedi who will become Darth Vader, had been "attached" to the idea of saving his family, Yoda says.

"Mourn them, do not. Miss them, do not. Attachment leads to jealousy. The shadow of greed, that is."

'Clear, your mind must be'

Earlier

this month, the East Bay Meditation Center in Oakland, California,

hosted a workshop called "Jedi Insights: A Force For Justice." About 40

people turned out, including several teenagers and new meditators.

Ikeda,

who co-led the workshop, said many teens are like Rey, the

inexperienced but enthusiastic Jedi: looking for mentors to help

unravel the mystery of self-knowledge.

"They're like, please, please, please, give me that spiritual training," Ikeda said.

During

the workshop, Ikeda and her co-teacher, John Ellis, discussed "Star

Wars" scenes and led guided meditations. Inevitably, a few lively lightsaber battles broke out. Almost as inevitably, because this is America in 2018, the discussion got political.

"There's

so much going on, from the environment to taxes to education, that it's

easy to be overwhelmed," Ellis said. "'Star Wars' help us think about

how meditation teaches us to focus on the task at hand, and bring our

best self to it."

'A pile of old books'

So what is the spiritual message in "The Last Jedi," and what -- if anything -- can it tell us about religion in real life?

It's true that millennials may be eager for spiritual training, but they are are increasingly unlikely to identify with a specific religion. Nearly one in three says they have no religious affiliation.

But let's take a closer look at why millennials are leaving, or forsaking, the fold.

A new study of young former Catholics,

conducted by St. Mary's Press Catholic Research Group and Georgetown

University's Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate, found that

more blamed their family for the decision to leave the church than the

church institution itself. Only 11% said they quit Catholicism because

they oppose the church or religious institutions in general.

The

study also found that nearly half had joined other religious

communities, including other Christian ones. So is organized religion

really the issue here?

It's no

secret that we're living during a time of seismic shifts, from

technology to politics to spirituality. It's not so much an "era of

changes," Pope Francis has said, as a "change of eras."

So what's the leader of a 2,000-year-old church to do?

The

answer is not resurrecting "obsolete practices and forms," Francis

says. Some Catholic customs, while beautiful, "no longer serve as means

of communicating the Gospel."

But

the Pope is no iconoclast, eager to discard sacred traditions. In fact,

he wants Catholics to go back to the roots of their religion, the

Gospel.

Francis has repeatedly

implored Christians, particularly priests, to put Jesus' words into

action by caring for the sick, the lame and the poor. He wants shepherds

who smell like their sheep, not bookkeepers who smell like sheepskin.

Which brings us back to the spiritual message encoded in "The Last Jedi."

As

Luke prepares to torch the tree containing the sacred Jedi texts, Yoda

appears out of nowhere and does the deed himself, cackling all the

while.

"Time it is," Yoda says, "for you to look past a pile of old books."

Some fans were aghast that Yoda would feign sacrilege against the Jedi tradition.

But when you look at the scene from a Buddhist lens, the meaning shifts.

Zen

is full of stories about ancient masters trying to jolt their

apprentices from mental ruts. In one ancient monastery, the students

paid too much attention to Buddhist images, so the head monk torched

them. ("If you see the Buddha, kill the Buddha," says a famous koan.)

These

lessons and koans are not meant to be permanent prescriptions for all

Buddhists for all time. They're highly particular, transmitted from

master to apprentice, one mind to another.

In

that light, maybe Yoda's apparent willingness to burn the "old pile of

books" isn't really about texts, which he already knows are safely in

Rey's possession. Maybe it isn't even about religion. It's just about

Luke.

Yoda is trying to shock him

out of his guilt and shame about the past, and make him focus on "the

need in front of (his) nose," the Resistance that could sorely use a

little saving.

So perhaps the

real spiritual message of "Star Wars" isn't about the end or beginning

of organized religion. Maybe, like a good Zen teacher, it's a mirror

showing us our own minds. Are we preoccupied with the past, concerned

about the future, or paying attention to the needs in front of our

noses?

No comments:

Post a Comment