Some people here in the 21st century still think of solar power as a futuristic, unproven technology. But solar-powered machines have been around for well over a century.

In a short article called “Electricity From the Sun,” the October 1923 issue of Science and Invention magazine told the story of a German dream to build a gigantic lens that would be able to harness the sun and convert its energy into electricity for an entire town.

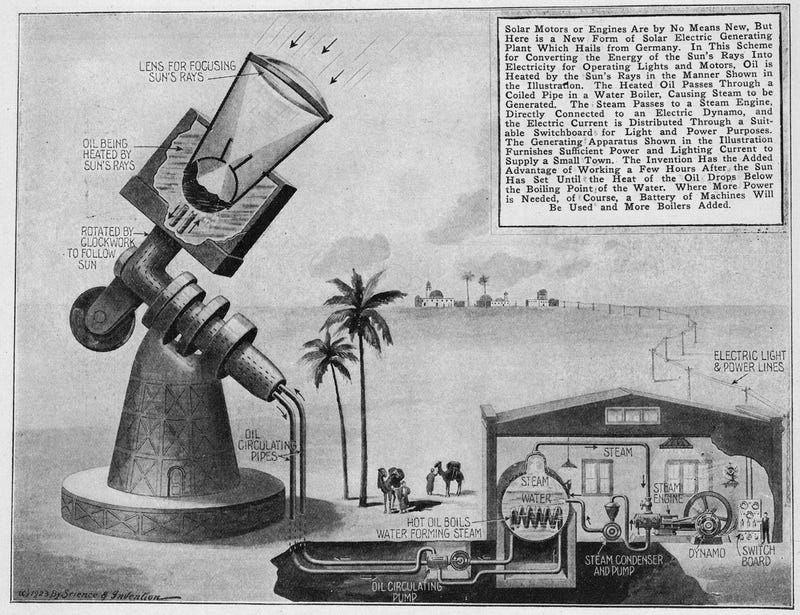

The lens would be mounted on an enormous swiveling hinge that would be timed to follow the sun, much like the rotating “follow the sun” houses imagined in the 1950s. The lens would concentrate the sun’s energy and heat up oil, creating steam. That steam would then power a generator, and from there, electric power could be brought to homes in the area.

As far as we know, this solar power plant was never actually built in any way. But it was a fantastic dream at a time when most people around the world still didn’t have electricity in their homes. In fact, just 35 percent of Americans had electricity at home in 1920. And for rural residences it was even lower than that. Just 3 percent of American farms had electricity at the start of the 1920s.

But this invention was supposed to change all that, especially in rural desert areas, as you can see from the illustration. This radical design was supposed to turn the sun into a reliable source of electricity for people around the world.

From the 1923 issue of Science and Invention:

Solar motors or engines are by no means new, but here is a new form of solar electric generating plant which hails from Germany. In this scheme for converting the energy of the sun’s rays into electricity for operating lights and motors, oil is heated by the sun’s rays in the manner shown in the illustrationThe heated oil passes through a coiled pipe in a water boiler, causing steam to be generated. The steam passes to a steam engine, directly connected to an electric dynamo, and the electric current is distributed through a suitable switchboard for light and power purposes.The generating apparatus shown in the illustration furnishes sufficient power and lighting current to supply a small town. The invention has the added advantage of working a few hours after the sun has set until the heat of the oil drops below the boiling point of the water. Where more power is needed, of course, a battery of machines will be used and more boilers added.

Based on this description, it’s fair to say that this is an example of steam power as much as it is solar power. But that’s how the “solar power” of the 19th century often worked. For example, this solar-powered printing press from 1882 used the sun’s rays to print a newspaper.

French inventor Abel Pifre showed off his invention on August 6, 1882 at the Gardens of the Tuilleries in Paris. Pifre’s machine brought 50 liters of water to a boil in just under an hour, driving a 2/5ths horsepower engine that was attached to his printing press. The inventor was reportedly able to print up to 500 copies an hour of his Soleil-Journal, or “Sun Journal.”

This method of solar energy creating steam was exactly how things like this 1937 solar-powered fridge worked as well. But steam hasn’t always been so environmentally friendly. The first steam-powered cars were often powered by burning wood. Amazingly, roughly 40 percent of American-made cars in the year 1900 were powered by steam. And then there were, of course, America’s steam-powered iron horses that ran on coal.

Whether it’s steam-powered cars or solar-powered printing presses, it’s easy for those of us here in the 2010s to forget that a lot of this eco-friendly technology has been around for over 100 years. But there’s nothing new.... under the sun.

end quote from:

No comments:

Post a Comment