"The labor market has continued to strengthen and the economic activity has been rising at a strong rate," the Federal Open Market Committee said in its policy statement. "Jobs have been strong."

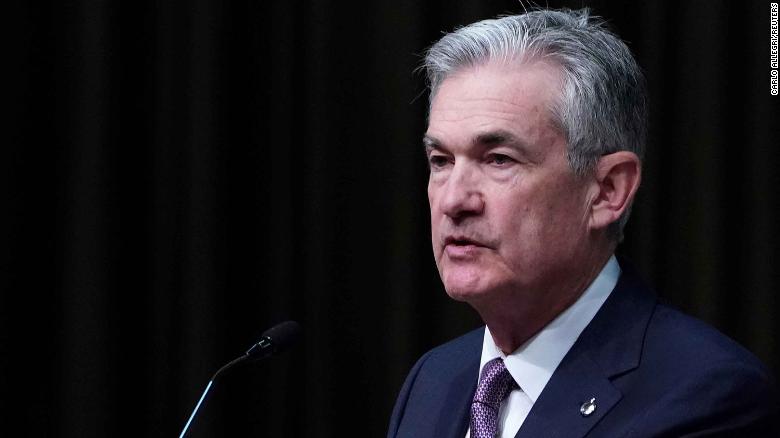

Central bankers unanimously agreed under Chairman Jerome Powell to lift the federal funds rate, which controls the cost of mortgages, credit cards and other borrowing to a range of 2.25% and 2.5%.

At their final two-day policy-setting meeting in Washington, policymakers also signaled they would be willing to throttle back on its planned rate increases in 2019 amid growing concerns about a softening economy and rising market volatility.

In their statement, policymakers made clear they are attuned to global and financial headwinds facing the US economy, and said they would continue to monitor developments and the impact on their outlook going forward.

The decision by the Fed comes after an

unprecedented public pressure campaign by Trump.

On Tuesday, as officials gathered in Washington for the start of their two-day meeting, the President urged the Fed to move cautiously "before they make another mistake."

Interest rates have gone up seven times since Trump took office. Four of those increases have been under Powell.

The president's repeated remarks have

put his Fed chairman in an awkward position amid signs of economic softening and weeks of market volatility that have shaken the broad consensus that rates must go up.

Any deviation from that plan going forward could be read as a sign of Powell caving to Trump and spark a wild selloff by stocking concerns that even the Fed thinks the economy is turning south.

"The December FOMC meeting will be about one thing and one thing alone for investors: How many rate hikes does the Fed think will be appropriate in 2019?" Ellen Zentner, chief US economist at Morgan Stanley, wrote in a note to clients ahead of the meeting.

Central bankers are now wrestling with tighter financial conditions -- mainly reflecting a stock selloff -- which has increased the odds of growth slowing next year. Fed officials slightly marked down their growth forecast for this year and 2019, dropping to 3% and 2.3%, respectively. They had previously predicted economic growth to be 3.1% and 2.5% for 2018 and 2019.

As a result, the Fed sent a dovish signal to investors, lowering their projections of how many rates they expect next year in their so-called "dot plot." The central bank now appears to be eyeing at least two more rate hikes in 2019. Only six FOMC participants expect there could be as many as three.

In September, nine of the 16 policy makers forecast the Fed should raise rates three or more times next year, while seven officials estimated the economy would benefit from two hikes or less.

Powell has repeatedly tried to advise investors not to read too deeply into the Fed's economic forecasts, saying policymakers often don't have the ability to see that far into the future and

decisions are formed based on data from markets, the economy and business contacts.

The US central bank has been trying to strike a balance between not moving too fast and risking shortening the economy's longest running expansion versus not moving too slowly and risking the economy overheating.

Instead, it has signaled a shift toward "data dependence," meaning going forward it will only become less clear just how fast the Fed plans to raise rates to keep the US economy from wobbling.

Even so, policy makers didn't go as far as expected in removing a commitment to gradually continue to raise rates next year -- a move the market anticipated could have come as early as December.

At their last meeting in November, Fed officials suggested potentially changing their post-meeting statement to remove mention of "further gradual increases" and reflecting their plans to rely more greatly on fresh economic data.

The potential pivot by the Fed prompted one Wall Street analyst, Goldman Sachs' chief US economist Jan Hatzius, to declare ahead of the meeting in a note to clients: "The end of gradual."

No comments:

Post a Comment