begin quote from:

Origin of ice age theory

Origin of ice age theory

-4500 —

–

-4000 —

–

-3500 —

–

-3000 —

–

-2500 —

–

-2000 —

–

-1500 —

–

-1000 —

–

-500 —

–

0 —

Axis scale: millions of years.

Orange labels: known ice ages.

Also see: Human timeline and Nature timeline

Orange labels: known ice ages.

Also see: Human timeline and Nature timeline

Meanwhile, European scholars had begun to wonder what had caused the dispersal of erratic material. From the middle of the 18th century, some discussed ice as a means of transport. The Swedish mining expert Daniel Tilas (1712–1772) was, in 1742, the first person to suggest drifting sea ice in order to explain the presence of erratic boulders in the Scandinavian and Baltic regions.[12] In 1795, the Scottish philosopher and gentleman naturalist, James Hutton (1726–1797), explained erratic boulders in the Alps by the action of glaciers.[13] Two decades later, in 1818, the Swedish botanist Göran Wahlenberg (1780–1851) published his theory of a glaciation of the Scandinavian peninsula. He regarded glaciation as a regional phenomenon.[14]

The Antarctic ice sheet. Ice sheets expand during an ice age.

Variations in temperature, CO2, and dust from the Vostok ice core over the last 400,000 years

In 1829, independently of these debates, the Swiss civil engineer Ignaz Venetz (1788–1859) explained the dispersal of erratic boulders in the Alps, the nearby Jura Mountains, and the North German Plain as being due to huge glaciers. When he read his paper before the Schweizerische Naturforschende Gesellschaft, most scientists remained sceptical.[19] Finally, Venetz convinced his friend Jean de Charpentier. De Charpentier transformed Venetz's idea into a theory with a glaciation limited to the Alps. His thoughts resembled Wahlenberg's theory. In fact, both men shared the same volcanistic, or in de Charpentier's case rather plutonistic assumptions, about the Earth's history. In 1834, de Charpentier presented his paper before the Schweizerische Naturforschende Gesellschaft.[20] In the meantime, the German botanist Karl Friedrich Schimper (1803–1867) was studying mosses which were growing on erratic boulders in the alpine upland of Bavaria. He began to wonder where such masses of stone had come from. During the summer of 1835 he made some excursions to the Bavarian Alps. Schimper came to the conclusion that ice must have been the means of transport for the boulders in the alpine upland. In the winter of 1835 to 1836 he held some lectures in Munich. Schimper then assumed that there must have been global times of obliteration ("Verödungszeiten") with a cold climate and frozen water.[21] Schimper spent the summer months of 1836 at Devens, near Bex, in the Swiss Alps with his former university friend Louis Agassiz (1801–1873) and Jean de Charpentier. Schimper, de Charpentier and possibly Venetz convinced Agassiz that there had been a time of glaciation. During the winter of 1836/37, Agassiz and Schimper developed the theory of a sequence of glaciations. They mainly drew upon the preceding works of Venetz, de Charpentier and on their own fieldwork. Agassiz appears to have been already familiar with Bernhardi's paper at that time.[22] At the beginning of 1837, Schimper coined the term "ice age" ("Eiszeit") for the period of the glaciers.[23] In July 1837 Agassiz presented their synthesis before the annual meeting of the Schweizerische Naturforschende Gesellschaft at Neuchâtel. The audience was very critical and some opposed to the new theory because it contradicted the established opinions on climatic history. Most contemporary scientists thought that the Earth had been gradually cooling down since its birth as a molten globe.[24]

In order to overcome this rejection, Agassiz embarked on geological fieldwork. He published his book Study on Glaciers ("Études sur les glaciers") in 1840.[25] De Charpentier was put out by this, as he had also been preparing a book about the glaciation of the Alps. De Charpentier felt that Agassiz should have given him precedence as it was he who had introduced Agassiz to in-depth glacial research.[26] Besides that, Agassiz had, as a result of personal quarrels, omitted any mention of Schimper in his book.[27]

All together, it took several decades until the ice age theory was fully accepted by scientists. This happened on an international scale in the second half of the 1870s following the work of James Croll, including the publication of Climate and Time, in Their Geological Relations in 1875, which provided a credible explanation for the causes of ice ages.[28]

Evidence for ice ages

There are three main types of evidence for ice ages: geological, chemical, and paleontological.Geological evidence for ice ages comes in various forms, including rock scouring and scratching, glacial moraines, drumlins, valley cutting, and the deposition of till or tillites and glacial erratics. Successive glaciations tend to distort and erase the geological evidence, making it difficult to interpret. Furthermore, this evidence was difficult to date exactly; early theories assumed that the glacials were short compared to the long interglacials. The advent of sediment and ice cores revealed the true situation: glacials are long, interglacials short. It took some time for the current theory to be worked out.

The chemical evidence mainly consists of variations in the ratios of isotopes in fossils present in sediments and sedimentary rocks and ocean sediment cores. For the most recent glacial periods ice cores provide climate proxies from their ice, and atmospheric samples from included bubbles of air. Because water containing heavier isotopes has a higher heat of evaporation, its proportion decreases with colder conditions.[29] This allows a temperature record to be constructed. However, this evidence can be confounded by other factors recorded by isotope ratios.

The paleontological evidence consists of changes in the geographical distribution of fossils. During a glacial period cold-adapted organisms spread into lower latitudes, and organisms that prefer warmer conditions become extinct or are squeezed into lower latitudes. This evidence is also difficult to interpret because it requires (1) sequences of sediments covering a long period of time, over a wide range of latitudes and which are easily correlated; (2) ancient organisms which survive for several million years without change and whose temperature preferences are easily diagnosed; and (3) the finding of the relevant fossils.

Despite the difficulties, analysis of ice core and ocean sediment cores[30] has shown periods of glacials and interglacials over the past few million years. These also confirm the linkage between ice ages and continental crust phenomena such as glacial moraines, drumlins, and glacial erratics. Hence the continental crust phenomena are accepted as good evidence of earlier ice ages when they are found in layers created much earlier than the time range for which ice cores and ocean sediment cores are available.

Major ice ages

Ice age map of northern Germany and its northern neighbours. Red: maximum limit of Weichselian glacial; yellow: Saale glacial at maximum (Drenthe stage); blue: Elster glacial maximum glaciation.

Rocks from the earliest well established ice age, called the Huronian, formed around 2.4 to 2.1 Ga (billion years) ago during the early Proterozoic Eon. Several hundreds of km of the Huronian Supergroup are exposed 10–100 km north of the north shore of Lake Huron extending from near Sault Ste. Marie to Sudbury, northeast of Lake Huron, with giant layers of now-lithified till beds, dropstones, varves, outwash, and scoured basement rocks. Correlative Huronian deposits have been found near Marquette, Michigan, and correlation has been made with Paleoproterozoic glacial deposits from Western Australia.

The next well-documented ice age, and probably the most severe of the last billion years, occurred from 850 to 630 million years ago (the Cryogenian period) and may have produced a Snowball Earth in which glacial ice sheets reached the equator,[33] possibly being ended by the accumulation of greenhouse gases such as CO2 produced by volcanoes. "The presence of ice on the continents and pack ice on the oceans would inhibit both silicate weathering and photosynthesis, which are the two major sinks for CO2 at present."[34] It has been suggested that the end of this ice age was responsible for the subsequent Ediacaran and Cambrian explosion, though this model is recent and controversial.

The Andean-Saharan occurred from 460 to 420 million years ago, during the Late Ordovician and the Silurian period.

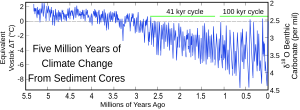

Sediment records showing the fluctuating sequences of glacials and interglacials during the last several million years.

The current ice age, the Pliocene-Quaternary glaciation, started about 2.58 million years ago during the late Pliocene, when the spread of ice sheets in the Northern Hemisphere began. Since then, the world has seen cycles of glaciation with ice sheets advancing and retreating on 40,000- and 100,000-year time scales called glacial periods, glacials or glacial advances, and interglacial periods, interglacials or glacial retreats. The earth is currently in an interglacial, and the last glacial period ended about 10,000 years ago. All that remains of the continental ice sheets are the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets and smaller glaciers such as on Baffin Island.

Ice ages can be further divided by location and time; for example, the names Riss (180,000–130,000 years bp) and Würm (70,000–10,000 years bp) refer specifically to glaciation in the Alpine region. The maximum extent of the ice is not maintained for the full interval. The scouring action of each glaciation tends to remove most of the evidence of prior ice sheets almost completely, except in regions where the later sheet does not achieve full coverage.

Evidence of a recent, extreme ice age on Mars was published by the journal Science in 2016. Just 370,000 years ago, the planet would have appeared more white than red.[35]

No comments:

Post a Comment