For those of you who have not studied Brahmanism, Hinduism or Buddhism (Buddhism in some ways is similar to what the Catholic church(Hinduism) is to Protestantism(Buddhism). This is because a Brahman Prince of Lumbini started a religion that by some is considered an evolution of Hinduism. IN places like Japan, China, India, sex is not considered a taboo or bad thing to them but the essence of life itself. They don't believe in original sin (at least not like Christians do) in regard to Adam and Eve.

They have their own constraints for example, it is not proper for a man to touch a woman in any way in public including holding her hand or hands. This would be very offensive in Chinese, Indian and Japanese culture. However, men can walk around hanging all over each other and this is acceptable. The apparent reason is anything that doesn't result in a baby out of wedlock is not necessarily bad.

However, not being from Asia this might be steering you wrong in some ways as an American viewpoint.

However, having been in India, Nepal, Thailand and Japan and South Korea I have seen this on the streets and the dirty looks I was given if I held my wife's hand or put my arm around her any time we were in public in any of these countries.

begin quote from:

Lingam

Lingam

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Shivling" redirects here. For the mountain, see Shivling (Garhwal Himalaya). For the 2016 film, see Shivalinga (2016 film). For the 2017 film, see Shivalinga (2017 film). For other uses, see Linga (disambiguation).

| Part of a series on |

| Shaivism |

|---|

|

Traditional flower offering to a lingam in Varanasi

The lingam is often represented alongside the yoni (Sanskrit word, literally "origin" or "source" or "womb"), a symbol of the goddess or of Shakti, female creative energy.[5] The union of linga and yoni represents the "indivisible two-in-oneness of male and female, the passive space and active time from which all life originates".[6]

Contents

Definition

A 10th-century four-headed stone lingam (Mukhalinga) from Nepal

Origin

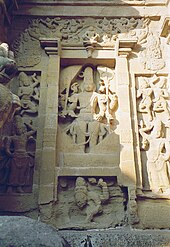

Lingodbhava Shiva: God Shiva appears as in an infinite Linga fire-pillar, as Vishnu as Varaha

tries to find the bottom of the Linga while Brahma tries to find its

top. This infinite pillar conveys the infinite nature of Shiva.[8]

There is a hymn in the Atharvaveda that praises a pillar (Sanskrit: stambha), and this is one possible origin of linga worship.[10] Some associate Shiva-Linga with this Yupa-Stambha, the sacrificial post. In the hymn, a description is found of the beginning-less and endless Stambha or Skambha, and it is shown that the said Skambha is put in place of the eternal Brahman. The sacrificial fire of the Yajna, its smoke, ashes and flames, the soma plant, and the ox that used to carry the wood for the Vedic sacrifice, gave rise to the conceptions of the brightness of Shiva's body, his tawny matted hair, his blue throat, and the riding on the bull of the Shiva. The Yupa-Skambha gave place in time to the Shiva-Linga.[11][12] In the Linga Purana the same hymn is expanded in the shape of stories meant to establish the glory of the great Stambha and the supreme nature of Mahâdeva (the Great God, Shiva).[12]

The Hindu scripture Shiva Purana describes the origin of the lingam, known as Shiva-linga, as the beginning-less and endless cosmic pillar (Stambha) of fire, the cause of all causes.[13] Lord Shiva is pictured as emerging from the Lingam – the cosmic pillar of fire – proving his superiority over the gods Brahma and Vishnu.[8] This is known as Lingodbhava. The Linga Purana also supports this interpretation of lingam as a cosmic pillar, symbolizing the infinite nature of Shiva.[8][11][12][14] According to the Linga Purana, the lingam is a complete symbolic representation of the formless Universe Bearer – the oval-shaped stone is the symbol of the Universe, and the bottom base represents the Supreme Power that holds the entire Universe in it.[15] A similar interpretation is also found in the Skanda Purana: "The endless sky (that great void which contains the entire universe) is the Linga, the Earth is its base. At the end of time the entire universe and all the Gods finally merge in the Linga itself." [16] In yogic lore, the linga is considered the first form to arise when creation occurs, and also the last form before the dissolution of creation. It is therefore seen as an access to Shiva or that which lies beyond physical creation.[17] In the Mahabharata, at the end of Dwaraka Yuga, Lord Shiva says to his desciples that in the coming Kali Yuga, He shall be not appear in any particular form, but shall be formless and yet omnipresent. Seek him within the self and you will soon find him, meditate on His omnipresence and gain His boons.

Historical period

A Shiva lingam worshipped at Jambukesvara temple in Thiruvanaikaval (Thiruaanaikaa)

1008 Lingas carved on a rock surface at the shore of the Tungabhadra River, Hampi, India

Types

| This section does not cite any sources. (December 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The Rasa linga or Parad Shiva linga is made of mercury. It is of great importance for Hindu devotees and is worshipped with complete process, belief, and devotion. It is worshipped to be strong physically, mentally, spiritually, and psychologically as well as to obtain protection from the natural calamities, evil power, disaster, and other bad effects. It is worshipped to get prosperity and positive strength as well as occurrence of Lakshmi.

The white marble Shiva linga is beneficial for people with a suicidal tendency. Worshipping this lingam changes the mind positively and prevents a suicidal attempt by removing negative thoughts. It is of great importance for devotees and is used for meditation purposes, avoiding suicidal thoughts, removing negative thoughts, and improving concentration levels.

Debates around Lingam as phallic symbol

In 1825 Horace Hayman Wilson's work on the lingayat sect of South India attempted to refute British notions[specify] that the lingam graphically represented a human organ and that it aroused erotic emotions in its devotees.[21]Monier-Williams wrote in Brahmanism and Hinduism that the symbol of linga is "never in the mind of a Shaiva (or Shiva-worshipper) connected with indecent ideas, nor with sexual love".[22] In contrast, Jeaneane Fowler believes the linga is "a phallic symbol which represents the potent energy which is manifest in the cosmos".[2] Some scholars, including David James Smith, believe that throughout its history the lingam has represented the phallus; others, including N. Ramachandra Bhatt, believe the phallic interpretation to be a later addition.[23] M.K.V. Narayan distinguishes the Siva-linga from anthropomorphic representations of Shiva, and notes its absence from Vedic literature, and its interpretation as a phallus in Tantric sources.[24]

At the Paris Congress of the History of Religions in 1900, Ramakrishna's follower Swami Vivekananda argued that the Shiva-Linga had its origin in the idea of the Yupa-Stambha or Skambha, the sacrificial post, idealized in Vedic ritual as the symbol of the Eternal Brahman.[11][12][25] This interpretation was in response to a paper read by Gustav Oppert, a German Orientalist, who traced the origin of the Shalagrama-Shila and the Shiva-Linga to phallicism.[26] According to Vivekananda, the explanation of the Shalagrama-Shila as a phallic emblem was an imaginary invention. Vivekananda argued that this explanation of the Shiva-Linga as a phallic emblem was brought forward by the most thoughtless, and was forthcoming in India in her most degraded times, those of the downfall of Buddhism.[12]

According to Swami Sivananda, the view that the Shiva lingam represents the phallus is a mistake.[15] The same sentiments were also expressed by H. H. Wilson in 1840.[27] Diana Eck believes that translators of Shiva Purana erroneously translated linga as "phallic emblem". She compares the mistranslation "as inadequate as it would be an interpretation of the Christian Eucharist that saw the rite first and foremost as ritual cannibalism, eating the body and drinking its blood".[28]

According to Hélène Brunner,[29] the lines traced on the front side of the linga, which are prescribed in medieval manuals about temple foundation and are a feature even of modern sculptures, appear to be intended to suggest a stylised glans, and some features of the installation process seem intended to echo sexual congress. Scholars such as S. N. Balagangadhara have disputed the sexual meaning of lingam.[30]

Naturally occurring lingams

Lingam in the cave at Amarnath

Shivling, 6,543 metres (21,467 ft), is a mountain in Uttarakhand (the Garhwal region of Himalayas). It arises as a sheer pyramid above the snout of the Gangotri Glacier. The mountain resembles a Shiva linga when viewed from certain angles, especially when travelling or trekking from Gangotri to Gomukh as part of a traditional Hindu pilgrimage.

A lingam is also the basis for the formation legend (and name) of the Borra Caves in Andhra Pradesh.

See also

- Banalinga

- Spatika Lingam

- Axis mundi

- Hindu iconography

- Lingayatism

- Jyotirlinga

- Mukhalinga

- Pancharamas

- Shaligram

References

- Balagangadhara, S. N. (2007). Antonio De Nicholas, Krishnan Ramaswamy, Aditi Banerjee, eds. Invading the Sacred. Rupa & Co. pp. 431–433. ISBN 978-81-291-1182-1.

Sources

- Basham, A. L. The Wonder That Was India: A survey of the culture of the Indian Sub-Continent before the coming of the Muslims, Grove Press, Inc., New York (1954; Evergreen Edition 1959).

- Schumacher, Stephan and Woerner, Gert. The Encyclopedia of Eastern Philosophy and Religion, Buddhism, Taoism, Zen, Hinduism, Shambhala, Boston, (1994) ISBN 0-87773-980-3.

- Chakravarti, Mahadev. The Concept of Rudra-Śiva Through the Ages, Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass (1986), ISBN 8120800532.

- Davis, Richard H. (1992). Ritual in an Oscillating Universe: Worshipping Śiva in Medieval India. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691073866.

- Drabu, V.N. Śaivāgamas: A Study in the Socio-economic Ideas and Institutions of Kashmir (200 B.C. to A.D. 700), New Delhi: Indus Publishing (1990), ISBN 8185182388.

- Ram Karan Sharma. Śivasahasranāmāṣṭakam: Eight Collections of Hymns Containing One Thousand and Eight Names of Śiva. With Introduction and Śivasahasranāmākoṣa (A Dictionary of Names). (Nag Publishers: Delhi, 1996). ISBN 81-7081-350-6. This work compares eight versions of the Śivasahasranāmāstotra. The preface and introduction (English) by Ram Karan Sharma provide an analysis of how the eight versions compare with one another. The text of the eight versions is given in Sanskrit.

- Kramrisch, Stella (1988). The Presence of Siva. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120804913.

Further reading

- Daniélou, Alain (1991). The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism. Inner Traditions / Bear & Company. pp. 222–231. ISBN 0-89281-354-7

- Versluis, Arthur (2008), The Secret History of Western Sexual Mysticism: Sacred Practices and Spiritual Marriage, Destiny Books, ISBN 978-1-59477-212-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lingam. |

But the basic and most common object of worship in Shiva shrines is the lingam.

. It was almost as if the linga had emerged to settle Brahma and Vishnu’s dispute. The linga rose way up into the sky and it seemed to have no beginning or end.

During September–October 1900, he [Vivekananda] was a delegate to the Religious Congress at Paris, though oddly, the organizers disallowed discussions on any particular religious tradition. It was rumoured that his had come about largely through the pressure of the Catholic Church, which worried over the 'damaging' effects of Oriental religion on the Christian mind. Ironically, this did not stop Western scholars from making surreptitious attacks on traditional Hinduism. Here, Vivekananda strongly contested the suggestion made by the German Indologist Gustav Oppert that the Shiva Linga and the Salagram Shila, stone icons representing the gods Shiva and Vishnu respectively, were actually crude remnants of phallic worship.

No comments:

Post a Comment