What occurs to me the deeper I study climate change is that there is much much more that people don't know about climate Change than they now think they know.

So, I'm not going to be surprised (if I am still alive 100 years from now still) to see that what people think climate change is being caused by is really really different than what people think now.

When people talk about climate change that are scientists it is like they know only about 10% to 20% of what they actually need to know about what is going on. So, what I'm saying here is: "We are not being told everything that is actually going on."

And this is not necessarily a conspiracy theory or anything like that. It's more like "People just don't know what the "F---" is actually going on in enough detail to really even begin to discuss it properly.

For example, are we in a Geomagnetic Excursion or Reversal?

No one knows for sure. And if they do they are not telling anyone about it (or they have been silenced permanently by governments) one of the two.

Because literally everything like the magnetosphere going down to zero to 10 percent of normal in the polar circles from what it was in the 20th Century would be explained by a reversal or an excursion without Greenhouse gases at all.

So, I guess what I'm saying here is people don't really know enough about "What is really going on?"

Yes. Greenhouse gases and methane melting in the permafrost and from under the sea are permanently changing our upper atmosphere into something else completely different than humans have ever seen before in the last 10,000 years.

But, what is causing all this? IS it JUST humans? Or is it really many things governments really don't want to talk about at all for a variety of reasons?

So, are these things slowly driving the human race extinct here on earth or what?

This is the question I would like better answered.

And what are ALL these things?

To the best of my ability I write about my experience of the Universe Past, Present and Future

Top 10 Posts This Month

- Rosamund Pike: Star of New Amazon Prime Series "Wheel of Time"

- Belize Barrier Reef coral reef system

- SNAP rulings ease shutdown pressure as Thune rebuffs Trump call to end filibuster

- Flame (the Giant Pacific Octopus) whose species began here on earth before they were taken to another planet by humans in our near future

- Learning to live with Furosemide in relation to Edema

- Earthquake Scientists Say It's Time to Start Paying Attention to Antarctica

- I put "Blue Sphere" into the search engine for my site and this is what came up.

- Siege of Yorktown 1781

- Nine dead, dozens injured in crowd surge at Hindu temple in southern India

- John Travolta Finally Breaks His Silence

Monday, November 30, 2015

Why do so many people worldwide not believe the climate is changing?

I think it's mostly about belief and what people around you tend to believe. For example, in the heartland of the U.S. where they are REALLY isolated from any other cultures by so much land, people tend to believe in Christianity over science.

I can understand this because though I also believed in Science I had been raised as a creationist(I had been taught that God Created everything instead of evolution).

So, when I went to college and took a Social Science Class and realized more people believed in evolution in this class than believed what I believed I was pretty upset and dropped out of college for a semester. In fact, it took me until I was 21 to resolve all this in my mind properly.

The way I resolved it was to realize the Creation theory was only a Theory and Darwin's Theory of evolution was only a theory and I didn't have to totally believe either one. This was just fine with me.

However, people in the heartland may not have been raised in Los Angeles like I was during the 1950s and 1960s and so wouldn't be as progressive as I was then or now.

So, why should they believe the climate is changing if their friends where they live don't either?

They really have no evidence because they likely don't believe in Science either, only Christianity.

So, if you believe in Christianity but not Science you aren't going to accept climate change.

In fact, you aren't going to accept Science as meaning anything at all because you don't believe in it.

I believe in Science and Christianity but I also believe in Buddhism and compassion which is where I believe Jesus got the idea of forgiveness from in the first place. (Buddha was 500 years before Christ).

But, unless you respect science and can think in scientific ways and know how to prove things to yourself climate change is going to sound like mumbo jumbo and might as well be another religion that people where you live just don't believe in at all.

So, what I'm saying here is "You're not going to make people believe in things they don't already believe in."

This is just logical.

I can understand this because though I also believed in Science I had been raised as a creationist(I had been taught that God Created everything instead of evolution).

So, when I went to college and took a Social Science Class and realized more people believed in evolution in this class than believed what I believed I was pretty upset and dropped out of college for a semester. In fact, it took me until I was 21 to resolve all this in my mind properly.

The way I resolved it was to realize the Creation theory was only a Theory and Darwin's Theory of evolution was only a theory and I didn't have to totally believe either one. This was just fine with me.

However, people in the heartland may not have been raised in Los Angeles like I was during the 1950s and 1960s and so wouldn't be as progressive as I was then or now.

So, why should they believe the climate is changing if their friends where they live don't either?

They really have no evidence because they likely don't believe in Science either, only Christianity.

So, if you believe in Christianity but not Science you aren't going to accept climate change.

In fact, you aren't going to accept Science as meaning anything at all because you don't believe in it.

I believe in Science and Christianity but I also believe in Buddhism and compassion which is where I believe Jesus got the idea of forgiveness from in the first place. (Buddha was 500 years before Christ).

But, unless you respect science and can think in scientific ways and know how to prove things to yourself climate change is going to sound like mumbo jumbo and might as well be another religion that people where you live just don't believe in at all.

So, what I'm saying here is "You're not going to make people believe in things they don't already believe in."

This is just logical.

Woodward County, Oklahoma: Why do so many here doubt climate change?

Source: CNN

Opinion: Common ground with climate skeptics 03:23

Story highlights

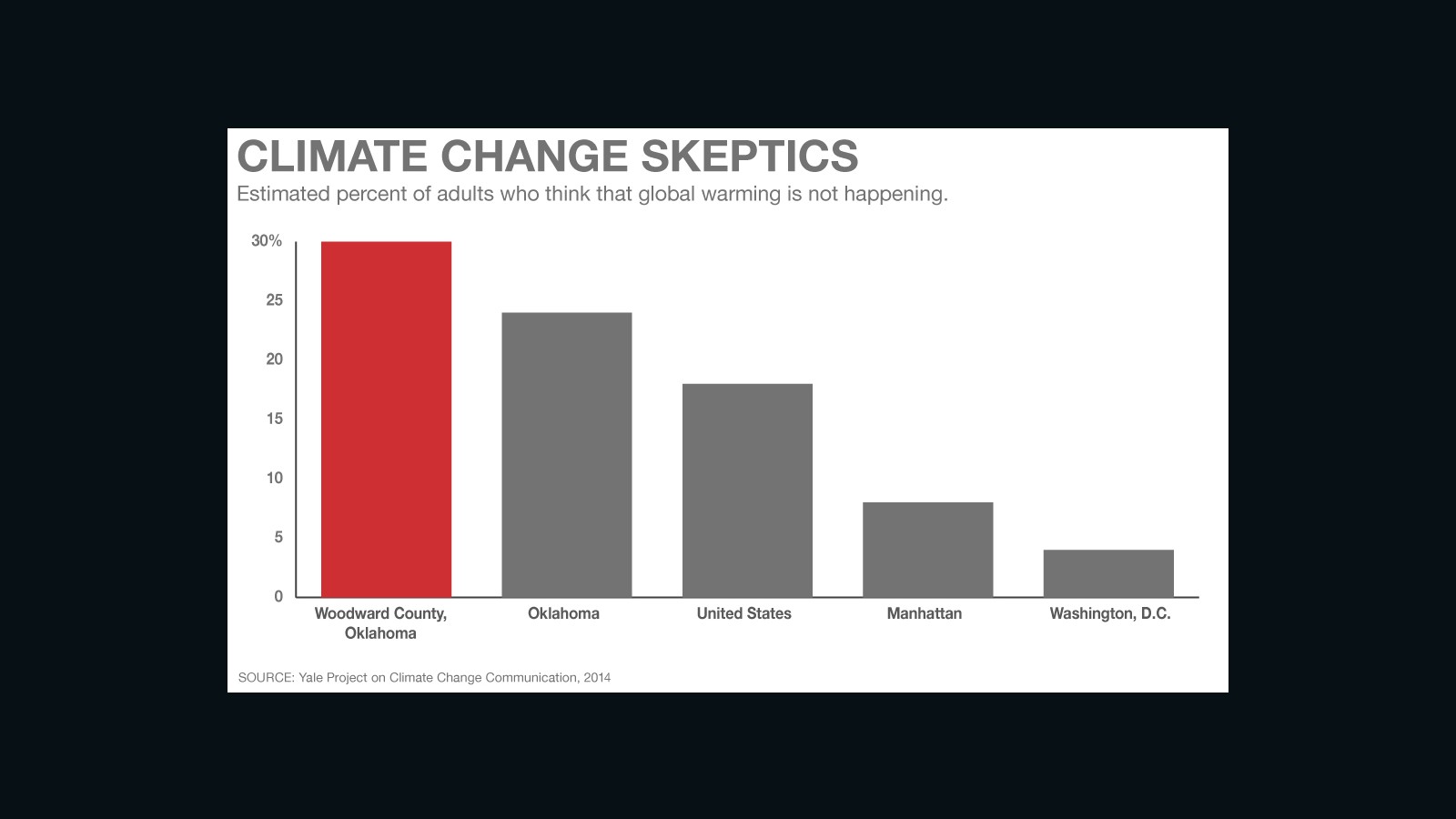

- John D. Sutter visits Woodward County, Oklahoma, where an estimated 30% of residents say climate change isn't real

- 97% of climate scientists say climate change is real and we're to blame

- Sutter: Skeptics and believers need to look for common ground

CNN columnist John D. Sutter is reporting on a tiny number -- 2 degrees -- that may have a huge effect on the future. He'd like your help. Subscribe to the "2 degrees" newsletter or follow him on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. He's jdsutter on Snapchat. You can shape this coverage.

Woodward, Oklahoma (CNN)I was wandering around the rolling plains of northwest Oklahoma looking for one person -- one person -- who believes in climate change science when I met the woman dressed all in yellow.

A

wide-brimmed, lemon-colored hat orbited her head. Her loafers were the

color of butter. Everything in between was a jubilee of sunshine.

Could she be the one?

Please, Lord, let her be the one.

I ask.

She laughs.

It's

a sweet laugh. A knowing laugh. A

yes-I-understand-everyone-out-here-thinks-climate-science-is-total-BS-but-I'm-the-one-who-gets-it

laugh.

Then Yellow Hat speaks.

"I think it's a big fat lie."

I

could recount several interactions like that from my week in Woodward

County, Oklahoma, one of the most climate-skeptical counties in the

United States. Thirty percent of the 21,000 people in Woodward County

are estimated (using a statistical model based in national surveys) to

believe that climate change isn't happening at all, according to the

Yale Project on Climate Change Communication. The county ties with six

others for the highest rate of climate skepticism in the country.

A

larger chunk of people in Woodward County, 42%, are estimated to say

maybe climate change is happening but we aren't causing it.

Those

views, of course, aren't supported by science. Climate change is real,

and we're contributing to it by burning gas for our cars and coal and

other fossil fuels to generate electricity. Saying otherwise flies in

the face of reality.

But out here,

where July temperatures hit 104 degrees Fahrenheit (40 Celsius) and the

often-gusting wind feels like a hair dryer aimed squarely at your face,

climate change is seen by some as nonexistent -- a farce, a conspiracy,

something that just plain doesn't make sense. Others who might be more

inclined to acknowledge climate change aren't eager to talk about it.

The subject is controversial to the point of being taboo. Several people

told me they'd never had a conversation about climate change until I

came around asking.

Others, like Yellow Hat, had anti-climate-science arguments locked and loaded.

"It's propaganda," she told me.

Like ... whose propaganda?

"The

presstitutes," among others, she said, probably not forgetting she was

speaking to a member of the international press, red CNN hat on head.

"They're bought and paid for."

I'll keep an eye out for the check.

In

Woodward, I'd learn about the art of "rollin' coal," which means

altering and then revving up a diesel engine so it emits thicker puffs

of smoke, mostly for the visual effect; I'd go mountain biking with a

guy who believes elements of "The Flintstones" are historically

accurate; I'd hear incorrect theories, like that hair spray, and other

aerosols, cause climate change, or that wind farms pollute more than

oil. And, clearly most important, a cowboy would ask me why I was

wearing stretch pants to a cattle auction. (They were Levi's 511s.)

Part

of me wants to write off the skeptics in Woodward County -- to think

that these views, especially the pants critique, are so out of sync with

the modern world, and so detrimental to efforts to cut carbon emissions

enough to stop the world from warming 2 degrees Celsius, which is regarded as the threshold for dangerous climate change,

that we should ignore them. That would be the easier thing to do, and

it's the approach some academics recommended to me, fearing reporting on

climate skeptics would pump oxygen onto the fire of misinformation.

"It

is a hopeless task to try to talk to them and change their minds," said

Stephan Lewandowsky, a psychology professor at the University of

Bristol.

But I don't want to ignore this place -- and don't think you should, either.

Partly that's because so many readers of CNN's Two° series on climate change

asked me to look into climate skepticism in the United States. You

wanted to know why such skepticism persists here, what's really behind

the sentiment -- and how skeptics, hopefully, can become part of

solutions to climate change.

Partly it's because I really came to love Woodward.

A sign in front of this statue reads, "A dinosaur like this roamed the Earth 5,000 years ago."

This

is a place that, like the rest of America, is far more messed up and

wonderful and complicated than we give it credit for. The real Woodward,

I found, is a place of confusion and silence -- where climate change is

often misunderstood, and where everyone but the most emboldened

skeptics appear nonexistent. This conversation is crucial, especially

after President Barack Obama's recent announcement that the United States will cut emissions

from coal-fired power plants and encourage renewable energy. And it's

important ahead of a presidential election where several frontrunners

are skeptical of climate science.

This

is a topic that is needlessly politicized. A narrow majority of people

in Woodward County say climate change is happening. Yet, they rarely

speak of it.

Plus, there's one other issue.

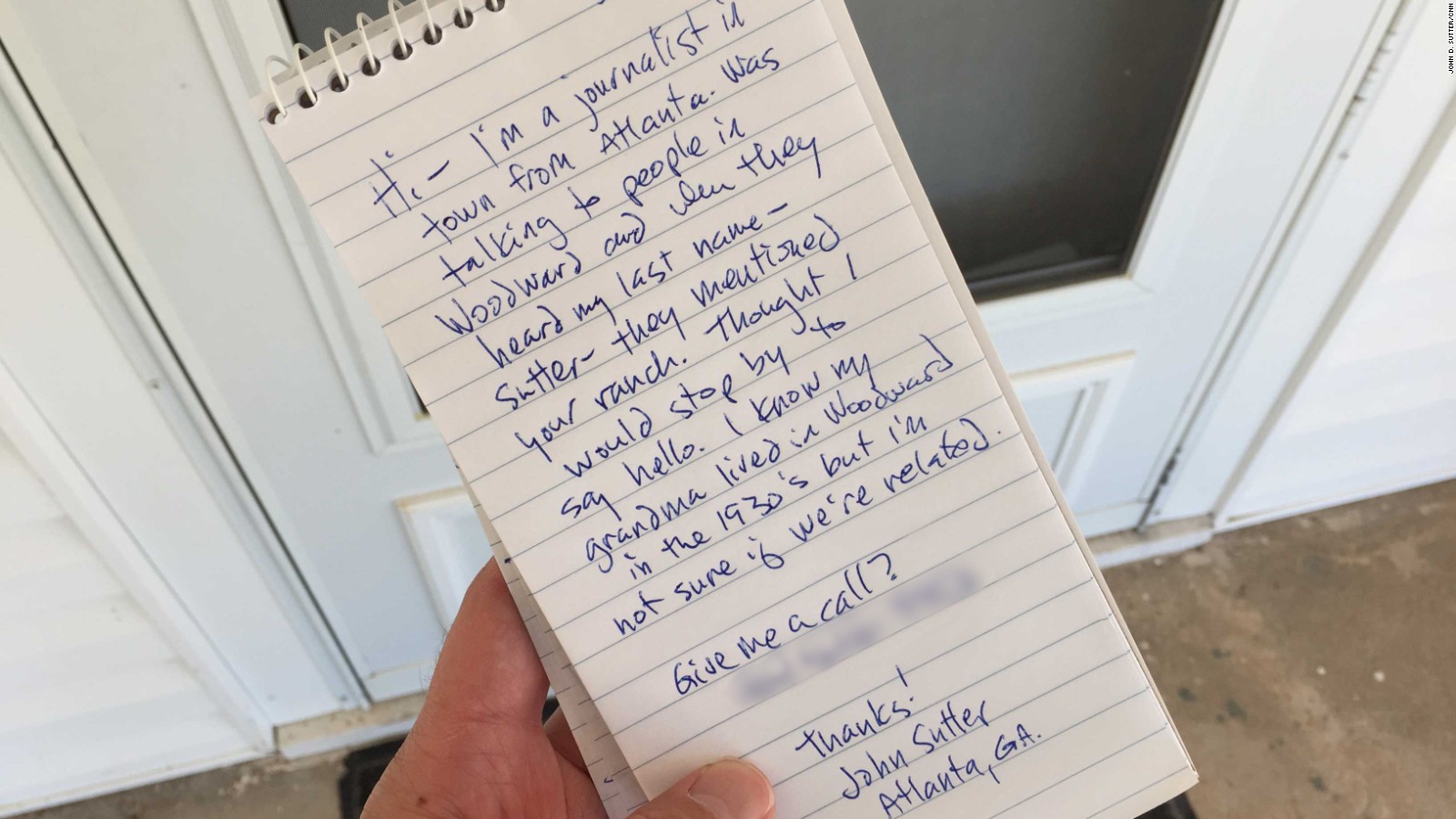

It's my name: John Sutter.

To

my surprise, it became the subject of much conversation in northwest

Oklahoma. Turns out, I have far more in common with this place than I

could have thought.

'I look for the truth'

I was frustrated with Woodward County before I arrived -- and for two reasons.

First,

I grew up in Oklahoma, near Oklahoma City, about 140 miles southeast of

Woodward. I thought I'd heard all of the worst-best arguments the

skeptics would have to make: that we need oil and gas jobs; that weather

patterns always are changing; that scientists are manipulating data to

trick us. I also knew that I'd meet fans of Jim Inhofe, the U.S. senator

from Oklahoma who is famous for calling climate change a "hoax." He

brought a snowball onto the Senate floor this year as if to say, OMG!

Snow! Where's your climate change now?

All

of that gives me a headache. I consider climate change one of the most

urgent human rights issues of our time. Earlier this year, I visited the Marshall Islands, a tiny country in the Pacific that might not exist for long if emissions aren't cut fast.

Homes already are flooding, and locals are worried about tides getting

higher, as sea levels rise because of warming temperatures. None of this

is their fault; it's ours, since we keep negligently burning fossil

fuels.

Second, there's the stegosaurus.

When

I Googled Woodward County, the weirdest thing came up: a Jurassic-era

dinosaur, about as tall as a one-story building, with a little girl

riding on its back.

Right in the heart of town.

A sign says, "A dinosaur like this roamed the Earth 5,000 years ago."

I

found that image to be so ridiculous. Five thousand years ago was the

Bronze Age, roughly the time the Egyptians were building pyramids. I'm

not a paleontologist, but I trust them, and their research suggests the

stegosaurus wasn't roaming the Earth with a little girl on its back.

That dinosaur lived about 150 million years ago, said Brian Huber,

chairman of the Paleobiology Department at the Smithsonian Institution.

"We have just a really high degree of confidence of this," he told me.

Modern humans, meanwhile, didn't evolve until 100,000 to 200,000 years

ago.

But that's not how everyone in Woodward sees it.

"I

think humans once lived with dinosaurs," said Randall Gabrel, a

53-year-old oil company owner and interim headmaster of Woodward

Christian Academy, who personally paid to install the statue in the

heart of town. (He declined to tell me exactly what that cost but did

offer that it was "more than a brand-new pickup truck.")

"I

don't know (that) a kid ever rode on a dinosaur," he told me, "but I

want to make this statement: that they lived at the same time."

His

sources? There are two. The Bible, which he interprets as saying God

created dinosaurs and humans on the same day. And a supposed dinosaur

bone sample, which he claimed to have sent to a university lab for

analysis. The problem: The bone was submitted for carbon-14 dating,

which, according to Jeff Speakman -- director of the Center for Applied

Isotope Studies at the University of Georgia, where documents indicate a

sample was sent -- can be used to date only material that is, at most,

about 55,000 years old. "It's absolutely impossible to radiocarbon-date

something that's 66 million years old," Speakman told me, citing the

date when scientists say the dinosaurs went extinct. That a dinosaur

bone would get any results at all indicates the bone was contaminated

with a more modern source of carbon, Speakman said.

Woodward County, Oklahoma, is estimated to have one of the nation's highest rates of climate skepticism.

Gabrel knows about those critiques but is undeterred.

"That's

what I believe," he told me. "I put (the stegosaurus statue) up there

because I think it draws attention, and I think the best evidence

supports that position. I'm willing to put my money where my mouth is.

I'm willing to stand by my beliefs."

"I look for the truth," he said. "That's what I'm after."

I'll let you guess what he thinks of climate change.

'Hard-ass place to live'

In

a state known for its weather -- tornadoes, ice storms, hail, heat

waves, floods, droughts all are normal in Oklahoma; and meteorologists

are among the state's biggest celebrities -- Woodward County is a case

study in extremes.

The day I drove to

Woodward, the sky was spitting rain and the car thermometer showed

temperatures in the upper 60s Fahrenheit (20 Celsius). A few days later,

the high was 104 degrees (40 Celsius), with a heat index of 108 (42

Celsius).

"This is a hard-ass place to

live. You been here?" said Rachael Van Horn, a senior reporter at the

local newspaper, The Woodward News, teasing me. "This is hard country."

This

"tough little piece of land" is in far northwestern Oklahoma, where

rolling prairies give way, to the west, to the board-flat infinity that

is the High Plains and, eventually, the Rocky Mountains. Trees are

relatively few out here, especially outside of town, so the sky in

Woodward County is big -- and mean.

The old-timers are best at explaining it.

Harold

Wanger, a cowboy hat-wearing 81-year-old, with a faint tuft of

monkey-grass hair sprouting from the tip of his nose, remembers dust

storms so thick they blotted out the sun. Wanger (pronounced like

"wrong-er") was born in 1934, near the start of an epic drought now

known as the Dust Bowl, when farmers overplowed the prairie, sending

walls of dirt racing across the plains, choking children with "dust

pneumonia," spoiling crops and sending thousands of "Okies" west to

California, a migration that John Steinbeck fictionalized in "The Grapes

of Wrath."

"The chickens went to bed

in the middle of the afternoon, it was so dark" when dust storms rolled

into Woodward County, Wanger told me.

He

was just a kid then, but Wanger recalls sleeping under wet sheets to

keep dirt out of his lungs. He'd wake up to see dust had piled up on the

floor overnight.

In the 1950s, just as

Wanger was finishing high school and getting married, extremely dry

conditions returned. He was just starting out as a wheat farmer and

cattle rancher, and Mother Nature wouldn't allow for much of either. "I

planted 1,800 acres of wheat in the fall of 1954 -- and didn't cut a

bushel."

Intense drought hit Oklahoma

again in the 2010s, this time breaking records. In 2011, the state

experienced "the hottest summer of any state since records began in

1895," according to the Oklahoma Climatological Survey, and Woodward saw

61 days at or above 100 degrees Fahrenheit). The drought dried up

streams, turned the short-grass prairie into straw and then helped it to

light ablaze.

It's impossible to say

climate change caused these or any other particular weather events, but

it is making these sorts of extremes more likely.

Climate

scientists expect droughts, heat waves and extreme rain events only to

get worse out here. The Southern Plains averages seven days per year

above 100 degrees Fahrenheit -- but that number is expected to quadruple

by 2050, according to the latest U.S. National Climate Assessment.

Water availability is expected to go down. Some crops probably will

shift northward. Winter wheat, for example, which is grown in Woodward

County, could see its yields decline by 15% if temperatures rise 2

degrees Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit). The amount of land burned by wildfires

in the Western United States is expected to spike sharply -- by 400% to

800% at 2 degrees Celsius of warming, according to a 2011 report from

the National Research Council.

Woodward, Oklahoma, is traditionally an oil and gas kind of place, but wind farms and solar pumps are becoming common, too.

Locals just shrug at those sorts of predictions, though.

"We're

used to it," said Sheila Gay, publisher of The Woodward News, which,

for the record, she said, has not written a local story focused on

climate change in the 18-some years that she's been working there.

"Welcome to Oklahoma."

'Most ludicrous myth'

I

came to Woodward to talk with skeptics. They, of course, were easy to

find. What was more difficult was finding someone who actually believed

in climate change.

So I made that a personal mission.

I wandered all over the county on a scavenger hunt for believers.

At

the Woodward Livestock Auction, I figured I'd meet ranchers affected by

the recent drought who wouldn't want to see that kind of thing

intensify and become more frequent. I met Jerry Nine, the rail-thin

auction owner, who told me ranchers have called him in tears during

drought years because they've had to sell nearly all of their cattle.

There isn't enough water for the cows to drink.

But

do these cattlemen buy climate science? "I think all this global

warming crap is overblown," said Wes Sander, one of the ranchers.

At

a church dinner, I met Genevieve Duncan, a soft-spoken 80-year-old who

walks with a cane. She told me climate change is "the most ludicrous

myth that has been forced upon the Earth since the world began."

Well, then.

I'm

paid to be persistent, so my quest for an eco-activist continued. At a

French cafe downtown, I met Rita Barney, who has bleached hair, cat-eye

glasses and tattoos everywhere. She looks like punk-climate-activist

material. But even she doesn't think we need to switch off of oil. "I

think that, as we take the oil out of the ground," she said, "God

provided a way for that to replenish itself." (Oil actually takes

hundreds of thousands of years under pressure to form.)

I

visited the High Plains Technology Center, which is one of the best

schools in the country for training people who work on wind farms. The

students I encountered were from California, New York, Missouri and

elsewhere. In the last five years or so, dozens of wind turbines have

popped up in and around Woodward, capitalizing on the wind that, true to

the song from the musical "Oklahoma!" does go sweeping down the plains.

Jack Day, 44, is one of the wind tech instructors there.

Does he think humans are causing climate change?

"My instinct is no."

Others declined to comment.

They

included Alan Riffel, the city manager, and Robert Roberson, a local

Prius driver and executive director of the Plains Indians & Pioneers

Museum.

I get the sense that many

people in Woodward are scared of what the "industry" might think of

their views on climate change -- and by "industry" they mean oil and

natural gas.

Despite the recent boom

in wind farms, which the city of Woodward features prominently on its

website, fossil fuels still drive the local economy.

Most

surprising, to me, however, was the sentiment of some relatives of

Norman Vanderslice, who died last year from injuries sustained in a

massive wildfire.

Steve and Julie

Milton told me Vanderslice, who was Steve's cousin but was more like a

brother to him, died trying to help another man escape the blaze. The

May 2014 fire, fueled by 50 mph winds, jumped a highway, Steve Milton

said, and burned Vanderslice so badly that he died after more than two

months in the hospital.

I told Steve

and Julie Milton about the predictions -- that wildfires in the western

United States are expected to increase in size by 400% to 800%.

"They can do all the research they want, and Mother Nature's gonna show

'em that she can do whatever she wants," Steve Milton said.

"If you look at history, it kinda repeats itself."

How (not) to argue with a skeptic

I'm

nonconfrontational by nature, but I found myself wanting to argue with a

few of the climate skeptics in Oklahoma -- or, in a couple of

instances, wanting to convince them they were wrong. I heard dozens of

people tell me, incorrectly, that climate change is "just a cycle," and

that it's natural, not man-made. But this theory, which also is parroted

by many Republican presidential candidates, is everywhere in Woodward.

Hearing it started to feel like an ice pick on my temples.

Steve and Julie Milton lost a relative in a 2014 wildfire. Such fires are expected to become more widespread.

I tried a number of methods.

The most tempting is this: Just the facts.

I've

honed my climate-change-is-real-and-we're-causing it argument down to

essentially three steps. This method is based on reading reports like

those by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the U.S. Global

Change Research Program and NASA, (including a brilliant Bloomberg illustration of NASA data),

as well as conversations with people like Katharine Hayhoe, a climate

scientist at Texas Tech. I turned to Hayhoe for help with this in part

because she's married to an evangelical minister and former skeptic. And

she convinced him this is real.

I

tried an abbreviated version of this approach on Mead Ferguson, 84, a

former worker for an international oil company and current rancher in

Woodward County.

Step one: We can see the climate is changing.

Most obviously, we see this in global average surface temperatures. But

glaciers also are melting, the ocean is getting warmer, plants are

blooming earlier, insects are moving north, rainfall and snowfall are

becoming more extreme, oceans are rising as they warm up and their

molecules expand, the oceans are becoming more acidic, etc., etc. It is

becoming impossible to dispute these facts, which is why you hear

skeptical politicians now arguing that it's happening, sure, but that we

have nothing to do with it.

Step two: We know it's not a natural cycle -- or related to sunspots. You

can make plenty of guesses about why the climate is warming, and all of

them are worth investigating. Thankfully, scientists have done that.

Sunspots, volcanoes, the Earth's orbit, natural variability, ozone

pollution. None of these -- even combined -- can explain the rapid rise

in temperature the Earth is already experiencing.

Step three: More than 97% of working climate scientists agree that we are causing climate change by burning fossil fuels and chopping down forests.

One factor clearly does explain why temperatures are getting warmer so

quickly: When we humans drive cars and burn fossil fuels to generate

electricity, we're releasing heat-trapping gases, mostly carbon dioxide,

into the atmosphere. These gases act like a blanket, gradually trapping

heat and causing warming.

This

doesn't mean that every summer will be sweltering, and that there won't

be any snow or ice. Far from it. Climate change is a gamble. We're

stacking the dice to make certain weather events more or less likely

over time. And while there may be some benefits from average warming,

the overall picture looks bleak, especially in the long term. If the

climate warms 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels (in June,

we'd already hit 0.88 degrees of warming), many low-lying island nations

probably will vanish, some crop yields probably will go down, water

probably will become much more scarce and 20% to 30% of plants and

animals will be put at risk for extinction.

Ferguson,

the rancher, was giving me a half-smiling death stare throughout my

mini-rant. We batted ideas back and forth several times, with him

pulling preclipped charts from an agricultural magazine off of his desk.

"We don't see an honest debate going on," he said.

One

of the charts, which used data from upper troposphere, appeared to show

that the climate isn't warming as much as scientists would expect. I

checked that out with Hayhoe, who told me this is a common data

manipulation: The upper troposphere is above the area of the atmosphere

where most carbon dioxide accumulates, meaning it's not a representative

way to measure climate change. Surface temperatures, from the lower

troposphere, are what we experience. (After this article was first

published, Hayhoe wrote me that, more importantly, there were errors in troposphere data, which are commonly misused by climate skeptics.)

Ferguson

also pointed me to a commentary, published in The Wall Street Journal,

that appeared to discount the peer-reviewed studies showing that 97% of

climate scientists agree that we're causing climate change by emitting

heat-trapping gases.

The reality,

Hayhoe told me, is that The Wall Street Journal's opinion section is not

peer-reviewed in the same way science is. And multiple peer-reviewed

studies have shown that publishing climate scientists are in

near-unanimous agreement about human-caused warming. Look at the actual

peer-reviewed research and the consensus is even greater. Of 25,182

climate change studies reviewed by James Powell, director of the

National Physical Science Consortium, only 26 studies, or 0.01% were found to reject the idea of human-caused climate change.

That's 99.9% agreement.

"We

as human beings have a tendency to put off what we really need to do if

it has the capacity to make us uncomfortable," said Rachael Van Horn, a

reporter at the Woodward News.

But Ferguson didn't buy it. He doesn't trust the Obama administration and says NASA and other federal agencies cook the books to toe the party line.

"I'm

in firm agreement you can't really argue this with charts," he said. "I

think people are arguing it with their hearts. Either you believe it or

you don't. ..."

I left the conversation feeling frustrated and confused.

Without agreement over these facts, how do we move forward?

'Survivors will be shot again'

My

increasingly foolhardy search for a climate change believer in Woodward

County got kicked into overdrive when I heard about a ranch with my

name on it.

You related to the Sutter Ranch folks? a local asked me.

I stared back blankly.

West of Woodward, the person said, near Fargo.

I'd had no idea there was a Sutter Ranch near Woodward County.

But I knew I had to find it.

My

motives were selfish. Secretly, I hoped these Ranching Edition Sutters

might be the climate change believers I'd been trying so hard to find. I

imagined them owning a wind farm. Woodward's hidden prairie hippies --

and with my last name!

How convenient.

I couldn't wait to find them.

First step on the search: My grandma.

She's

96. Still bright. And I remember her saying she lived somewhere in

western Oklahoma during the 1930s, around the time of the Dust Bowl. She

has stories about trying to outrun dust storms so she could pull

laundry in off the line.

I called her up from my hotel room in Woodward.

Did she know anything about a Sutter Ranch?

"I don't really know, John. If there is, I don't know anything about it."

OK, then. Step two: Hit the road.

Fargo

(population: 370) is all curled metal and splintered wood. The Saturday

I visited, the sun was hot enough to crinkle the horizon and the place

felt like a ghost town. I scanned for any signs of a person and spotted a

truck parked in front of what looked like an abandoned A-frame shed.

Against my better judgment, I pulled over.

Hello! ...?

Out walked a youngish guy with a gun.

"It's

just a pellet rife," he said, smiling as he read what must have been a

city boy expression on my face. "We work here. There's a pigeon problem

in the roof."

"You heard of Sutter Ranch?"

They

hadn't, so I drove around town until I saw a house that looked

welcoming enough to approach. A tall man with bird-talon toenails

answered the door and told me that the ranch was down the highway,

across the railroad tracks.

"I'm not sure what kind of reception you will get," he said.

How come?

They're pretty rich -- own lots of land, he said.

Great.

Now I was picturing the Sutters more like cartoonish, moneybags

Monopoly Men than climate change believers. I bet they didn't even have a

wind farm.

En route, I made a wrong

turn and pulled into a driveway with a sign that read, "Trespassers will

be shot. Survivors will be shot again."

I sped away.

'You contribute to the imbalance'

Once

I got it in my head that I might be related to people in Woodward

County, I started looking at the place a little differently.

What would my life be like if I had grown up on Sutter Ranch?

Would I still feel the same way about climate change, gay rights, gun control?

Would I still hate horses? (I really hate horses).

Just

the idea of being from here -- being of this place rather than an

outsider sent here to judge it -- made me realize that I was approaching

my time in Woodward all wrong. I intended to come to Woodward County to

listen to people. But I actually was tallying them up, putting them

into categories: believer vs. skeptic; rational human vs.

little-girl-on-the-back-of-a-stegosaurus statue owner. I was trying to

convince them I was right, not listening to where they were coming from.

Cattle

ranching and wheat farming are common in Woodward County. Winter wheat

yields could drop 15% if the climate warms 2 degrees Celsius.

"The

public in the United States doesn't speak with a single voice. They

have very different perspectives," said Anthony Leiserowitz, director of

the Yale Project on Climate Change Communication. "If you want to

engage the public effectively, you've got to start where they are, not

where you are."

I hadn't been taking that advice.

And

in doing so I'd gotten a warped view of this place. It turns out people

generally have a tendency to think that everyone either does -- or

should -- believe as they do. Academics sometimes call that sentiment

"pluralistic ignorance," which is a term I learned from George Marshall,

author of "Don't Even Think About It: Why Our Brains Are Wired to

Ignore Climate Change" and co-founder of the Oxford-based Climate

Outreach and Information Network.

"Pluralistic

ignorance" refers to the idea that, when no one talks about an issue --

or really listens -- it's easy to get a skewed view of reality. So,

let's say people in Woodward County express some degree of climate

skepticism because they assume that's how everyone else in the area

feels. In reality, no one's talking about the topic, so people tend to

overestimate how prevalent climate skepticism might be.

"If

you're a Republican in Oklahoma who accepts the science (of climate

change), you're likely to think everybody else out there disagrees with

it," Marshall told me. "And so you keep quiet. And when you keep quiet,

you contribute to the imbalance."

At

Marshall's urging, I started asking Woodward County residents what

percentage of their neighbors would say climate change is bunk.

Often, they'd guess 70% to 90%.

Based on my initial conversations, I would have said so, too.

The skeptics are the loudest. They stick in your head. Get the attention.

The

reality in Woodward County, however, according to the Yale research,

which used a national survey to estimate county-level data, with an 8%

margin of error, is that only 30% of people here think climate change is

fake.

Which isn't really that high when you think about it.

That's something I didn't realize at first.

All I heard were the highly skeptical arguments.

That's what I was primed to hear.

But

nationally, according to the Yale data, only 18% of people think

climate change isn't real. And only 9% of the national population feels

either "extremely" or "very" sure that climate change is not happening.

What that tells me is that the vocal, angry, conspiracy-theory-type

skeptics are a very small minority in this country.

Nine

percent of people are sure global warming is fake. The same percentage

of Americans also believe vaccines are more dangerous than disease.

In other words: It's a fringe view.

Many

more people, a more levelheaded read of the data reveals, are confused

by climate science, and with good reason. We in the news media do a poor

job of explaining it. And many of us who believe in climate change get

defensive and angry when we talk about it with skeptics. Meanwhile, only

one in 10 Americans know that nearly all climate scientists agree that

climate change is real and we're causing it by burning fossil fuels.

(One in 10!) And others aren't talking about this stuff at all. Three-quarters of Americans say they "rarely" or "never" discuss climate change with their family and friends

-- and those are the people who, statistically, are most likely to gain

their trust when it comes to this topic, after climate scientists.

In

Woodward, I found that for every person who vehemently denies climate

change is real -- the woman at the church dinner, for instance, who

called it a "ludicrous myth" -- there were several who felt genuinely

confused about the topic, or who had very rational and honest reasons to

avoid climate science.

Take Rita

Barney, the tattooed 58-year-old with the French restaurant downtown.

She thought hair spray caused climate change -- probably because she

used to be a hairdresser and heard, in the 1990s, that aerosol spray was

carving a hole in the ozone layer. Hair spray doesn't cause climate

change, but I understand her confusion. Both are issues dealing with the

atmosphere, and neither is talked about much here. (The ozone hole is

almost gone, by the way, thanks to international efforts to curb the use

of aerosols and certain refrigerants that were creating it.)

I

told her that burning fossil fuels and deforestation are the main

drivers of climate change -- and that's what scientists are concerned

about now.

"I'm not sure exactly what I

believe," she told me in response. "But I can tell you that just being a

part of this (interview) has made me more curious to study more and

find out. You know, if there's something that I can do personally (to

help)."

Jack Day, the wind farm technician trainer, had a similar reaction.

Two years ago, he would have said climate change is "malarkey," he told me.

But now he's in a gradual process of reconsidering.

"I think it's foolish to dismiss it completely," he said.

"It

comes down to trust, and I haven't found a good resource for myself.

... I'm pretty much a see-it-believe-it kind of guy. And I'm sure by

that time, it's too late."

'We aren't home at all'

The sign was just beyond the railroad tracks: "Sutter Ranch."

White letters on black paint.

Locusts

buzzed and grasshoppers shot from the ground like fireworks as the

belly of my tiny rental car dragged along the weed hump in the center of

the ranch's dirt road. I wasn't sure where I was going, but figured

this road had to lead somewhere. I crested a tiny hill and saw it: a

white ranch house and stable.

Two horses, one black, one brown, were in the pen.

Someone has to live here, I thought.

I

rang the doorbell and took note of my surroundings. The white house was

fairly nondescript except for one strange feature: the fence. Or,

rather, the lack of a fence. There was a tall metal gate, with a

swinging door, in front of the walkway that leads to the house. But no

fence on either side of it. Like the place is trying to give off the air

of being sectioned off from the rest of the world, but couldn't commit.

I rang the doorbell again. No answer.

I didn't see a soul, so I put a note on the door.

That

afternoon, I left quickly, worried someone would see me lurking around

the house and think I was some sort of city-hipster robber baron.

But

when I returned a second time, I got a little gutsier. I decided to

walk a loop around the house and spotted a second white building labeled

"Office." I knocked. Nothing. So I peeked into the window.

The

interior was hunting-lodge-meets-doublewide. I saw a horseshoe on the

wall. A cowboy hat. Plush furniture. And, most interestingly for my

purposes, a sign.

"Open most days about 9 or 10," the sign read.

Then where the hell are you?

"Occasionally

as early as 7," the sign continued. "But sometimes as late as 11 or 12.

Some days or afternoons we aren't home at all, and lately I've been

here just about all the time, except when I'm someplace else, but I

should be here then, too."

Perfect.

A Sutter Ranch riddle.

I

called the ranch number I'd found online and heard the office phone

ring -- the bleating rattle of a receiver that sounded like it was from

the 1970s or '80s.

My hopes were fading fast.

'I'm not Mr. Green'

The more time I spent in Woodward the more the place surprised me.

Take Randall Gabrel, the guy who paid for the dinosaur statue.

Despite

the fact that he owns an oil company and doesn't think humans are

causing climate change, he's spending more than $30,000, he told me, to

install 38 solar panels at his house, just west of Woodward (I almost

didn't believe this, but he showed me the panels and the frame, which

was under construction).

"If everyone

goes to solar, and that works, and that shuts down the oil and gas

industry, I'm good with it," he said. "If that works, then fine."

He

and other Woodward residents, in a strange way, are almost too humble

to believe man can contribute to climate change. Either they see the

weather as so big, so unpredictable, that they have to cow to Mother

Nature's whims. Or they believe that God is in control -- and that to

say we can shape the weather is almost like bragging, like making humans

seem far more significant than we actually are.

"That's

man saying, 'We're God, now.' That we're controlling the sun and the

Earth's environment," he said. "I don't know what the weather is going

to be like."

But he does care about pollution -- as well as saving money.

He wishes liberal politicians took this stuff seriously, too.

"I

don't think people are serious when they say stuff and they're not

willing to do it themselves," he said, referencing the fact that Barack

Obama and Al Gore continue to fly frequently and drive despite being

advocates for action on climate change.

Out here, this is just common sense.

If you say you believe something, you stand by it.

Eventually,

as I started listening harder, I also encountered a number of people

who believe climate change is a major issue for Woodward County and the

rest of the world.

One was a

12-year-old girl who I found spinning with her sister on a

merry-go-round on a sweltering afternoon. The girl, who I'm not

identifying because she's a minor, told me that climate change was a

no-duh sort of thing for her. She learned about it in science class, and

immediately told a bunch of her friends.

"They said, 'We don't have anything to do with that.' "

"They didn't make fun of me," she said. "They just didn't talk to me for a while."

"Nobody talks about it here," said the girl's sister, age 14.

Another

was Harold Wanger, the rancher who was born at the start of that

drought and who married his high school sweetheart during the next

drought cycle. He realizes that people can devastate the natural

environment -- he saw that happen when his family contributed to

overplowing the Great Plains during the Dust Bowl.

He doesn't want to see that happen again.

That's part of the reason he's leasing land to wind farms.

They're clean. No pollution.

"These

turbines are better than an oil well," he told me, standing beneath one

of the mammoth machines, which are nearly 300 feet tall and have blades

as long as blue whales. "An oil well will pump dry up on ya. And these

turbines will keep runnin'."

The other reason?

They pay him.

'W of City'

I decided to visit Sutter Ranch a third and final time.

On

the way, I stopped in Fargo, thinking maybe I'd find someone with a

clue about whether anyone actually lived on the Sutter land, or where

they might be. It seemed to me that they weren't living at the ranch

anymore.

I saw a few cars parked in

front of a community building in Fargo so I went in. That's where I ran

into Yellow Hat, the climate skeptic who insinuated I'm a "presstitute,"

pimping out my opinions on climate change for a few bucks from Al Gore,

George Soros, or whomever. She wasn't so helpful, but some of her

retired, card-playing buddies were. They dug through a pile of local

phonebooks with me to find one of the Sutter relatives whose name had

changed because of marriage.

Their address, off the ranch, was listed. It said, "W of City Fargo."

As in "West of Fargo."

Woodward

always has been a place of extremes. After being scorched in a drought,

the county now is seeing an unusually wet period.

Specific, huh.

But the card players knew the house.

Down the road, they said. Can't miss it.

I

wouldn't have the chance to. As I was driving out of town, I saw a

black truck pulling into Sutter Ranch. The black truck stopped in front

of a stable and next to a white truck with its hood popped up. I

followed at some distance and then parked my non-truck,

roller-skate-shaped rental car around the curve, facing the ranch exit.

Remembering the "survivors will be shot again" sign down the road, I

recalled the first rule of conflict-zone reporting: Know your exit

strategy.

I saw the man and watched him

go into the horse barn. I stood back some distance, hoping not to

startle him, and waited for him to come back outside.

I waved.

"Well, hi! Come in!" he said, smiling.

All the anxiety washed away.

My people, I thought.

Or hoped.

"Sit down if you don't mind getting dirty!"

I hopped on the gate of his pick-up and scanned for similarities.

Did this guy look like me?

Could we be related?

He

was wearing an Oklahoma State hat, which is the school both of my

parents attended. His mustache was kind of the same shape as mine, minus

my beard.

Both of those are pro-Sutter points, I guess.

"We've

been blessed with rain this year," the man at Sutter Ranch said. "Makes

a world of difference." The ranch was starting to look like Oz to me --

emerald fields of short grass prairie, sunflowers sprouting along the

roads.

I told the man why I was here

-- that my name was John Sutter, that my grandma lived nearby,

somewhere, during the 1930s, and that I was out here doing a story for

CNN on extreme weather and climate change, weirdly enough.

I

didn't tell him I was pinning all my hopes on this ranch's story --

that I somehow needed him to make sense of this science-skeptical place

for me.

Because that would have sounded bonkers.

He smiled and agreed to tell me the ranch's story.

His

name was Ken Merrill, married to Karen Merrill, formerly Sutter. So

forget what I said about our mustaches looking the same. Ken is married

into the Sutter clan.

The Sutter

family has been out here, just beyond the border of Woodward County,

since the early 1920s, he told me. The original Sutter -- O.E. Sutter

-- took a train ride across the prairie here, fell in love with the

land, and with the quail hunting opportunities, and bought the ranch.

The family was living in Wichita, Kansas, before that, where they worked

in the oil business. I remember my grandma talking about another branch

of our family that settled in that city while our Sutters stayed behind

and largely farmed.

I'm not certain, but it's likely we're distantly related.

Both families trace their roots to Pennsylvania.

I

was nervous to ask Ken -- and later Karen, his wife, who answered the

door wearing a golf visor, a wave of hair cresting over the brim --

about climate change. I started to think about my family -- many of whom

are deeply conservative and probably don't believe in climate change

either. They're good people. I love them dearly, but I'm sure we don't

see eye to eye on this or many other politicized issues.

Earlier,

I'd asked my 96-year-old grandma what she thought of climate change.

"Oh, I'm not smart enough to have an opinion on that," she'd told me.

That Oklahoma modesty.

I finally got up the courage to ask.

I felt like there was so much riding on the answer.

But once I heard it, I realized I'd been asking the wrong question.

"I think it's baloney," Karen Merrill told me.

It

didn't matter to me anymore that Karen Merrill -- or 30% of Woodward

and 18% of the United States -- didn't believe in climate change.

I believe it. I know why. And I can explain my views.

That's

important. Being willing to honestly, calmly explain the science to

skeptics, too, is crucial as well, since so much silence surrounds

climate change.

I wish people in

Woodward felt more able to speak up. And that politicians -- including

most Republicans who are parroting the line that they are "not

scientists," and global warming isn't our fault -- would realize the

damage they're causing.

This is an urgent crisis, and this country must be well-informed.

"Doomsday

predictions can no longer be met with irony or disdain," Pope Francis

wrote in his landmark encyclical on climate change, released earlier

this summer.

We already have a mandate

to move forward. The United States, long a laggard in international

climate negotiations, is pushing for action. President Obama, for

example, announced on Monday a plan to reduce emissions from power

plants 32% below 2005 levels by 2030. That's not going to fix

everything. But it's a big start. And it will give the United States

some moral ground to stand on when the world meets in Paris in December

to try to hammer out an international treaty.

Harold Wanger, 81, leases part of his ranch to wind farm developers.

Obama's

plan is described as controversial, but there's actually pretty broad

agreement that we need to be doing something -- even here in skeptical

Woodward. Seventy percent of people in Woodward (and 79% of Americans,

according to a 2015 poll by the Yale group) are estimated to support

funding for renewable energy research; 65% (75% of Americans) are

estimated to say we should regulate carbon as a pollutant; and a narrow

majority, 51%, (66% nationally) are estimated to say utilities should be

required to produce 20% of electricity from renewable sources.

If Woodward is the most skeptical place in America, we're doing well.

These

points of agreement should be our focus, not "belief" in climate

science. The United States needs to do a far better job about educating

the public about how and why climate change is happening, as well as the

very real dangers associated with it.

But solutions are what really matter.

Those

of us who think climate change is a problem should be open about our

beliefs and motives -- but we also must search for common ground with

unlikely allies.

"Oklahoma, and this

region of the country in particular, are pretty skeptical of things like

that," Ken Merrill told me. "I guess, mostly, it shows we've been

through it so many times, and it's just a cycle. You have your hot, you

have your cold.

"You have your wet times and your dry times."

That's

a skeptical view, sure. One that doesn't make clear humans are causing

climate change. But a moderate one, a reasonable one -- one based on his

personal experience of the uber-extreme weather people here always have

had to live with. It's especially reasonable given all of the

incentives for a person in Woodward County not to believe. Those

incentives are political, because conservative thought leaders insist on

denying climate change; economic, because oil and gas are still king in

Woodward, despite the wind boom; and religious, because not many

conservative Christian pastors are saying climate change is a moral

issue -- that the world's poor will be most affected, and that we have

an obligation to help.

But I have much more in common with Ken Merrill than our disagreement over whether humans are causing climate change.

It took far too long for me to realize that.

"I'm

a steward of the land out here," he told me. "It's my responsibility to

see that even in drought times, the land is taken care of and the land

is respected. We learned a lot from the Dust Bowl days, in terms of

farming practices. Nobody wants to go through that again. ... When you

grow up out here, that's just the mindset you learn. It becomes a way of

life. You take care of (the land) and it takes care of you.

"Generations

of our family survived out here just on what they had and what they

grew. If you didn't ever give back, the well is going to run dry

someday, so to speak."

I couldn't put it better myself.

This

story has been updated to reflect more-detailed information about

carbon 14 dating and contamination of supposed dinosaur bone samples.

end quote from:

| CNN International | - Nov 24, 2015 |

In a state known for its weather -- tornadoes,

ice storms, hail, heat waves, floods, droughts all are normal in

Oklahoma; and meteorologists are among the state's biggest celebrities

-- Woodward County is a case study in extremes.

ISIS caused this rift between Turkey and Russia

Without ISIS lusting after all of Syria and Iraq, Russia would not have felt he had to put Russian troops in Syria. Without putting Russian Jets in Syria nothing like just happened between Turkey and Russia would have occurred.

However, Russia is also mainly killing Sunnis who are not ISIS who want to overthrow Assad and many Turkmen and women take this very personally because they are the same religion and sometimes are relatives and friends of the ones Russia is Cluster bombing and hitting with missiles, and often they are civilians mostly women and children being killed. The reason for this is soldiers and their families often live together. So, in order to kill Anti-Assad Soldiers Russia has to kill everyone in those Sunni areas. So, 75% of the people in those areas are going to be women and children who are being cluster bombed and having missiles fall on their heads.

And the Turkish people know this and support the people and are friends and relatives of the men, women and children mostly being killed by Russia, Iran and the Syria Army now.

So, Russia is basically saying to Turkey, don't help your friends in Syria or we will go to war formally with you.

If you were Turkey what would you do?

However, Russia is also mainly killing Sunnis who are not ISIS who want to overthrow Assad and many Turkmen and women take this very personally because they are the same religion and sometimes are relatives and friends of the ones Russia is Cluster bombing and hitting with missiles, and often they are civilians mostly women and children being killed. The reason for this is soldiers and their families often live together. So, in order to kill Anti-Assad Soldiers Russia has to kill everyone in those Sunni areas. So, 75% of the people in those areas are going to be women and children who are being cluster bombed and having missiles fall on their heads.

And the Turkish people know this and support the people and are friends and relatives of the men, women and children mostly being killed by Russia, Iran and the Syria Army now.

So, Russia is basically saying to Turkey, don't help your friends in Syria or we will go to war formally with you.

If you were Turkey what would you do?

Russia and Turkey will both lose from Moscow's sanctions

| CNN | - 2 hours ago |

London

(CNN Money) - Russia has imposed economic sanctions on Turkey, even

though it might hurt itself in the process. Moscow has banned the import

of some Turkish goods, imposed restrictions on travel, and plans to

stop some Turkish companies ...

Designing something to wear so you don't die in 150 degrees Fahrenheit

The first thing I was thinking would be something like mylar or white that would reflect both sun and heat. The Second thing would be something to refrigerate the air so it wasn't so hot when you breathed it in. One way might be to breathe through ice to cool the air. However, ice likely wouldn't last very long but might last if it was one big piece with a hole through the center where you breathed in through to cool the air so it didn't burn your lungs at 150 degrees Fahrenheit. You wouldn't want to breathe out through it though because it might cause the ice to melt faster.

Why am I preparing for 150 degrees Fahrenheit? Temperatures with a heat index of 165 to 170 degrees already occurred in Pakistan and India last summer and are likely to do this or even increase in coming years in these locations or others as time goes on. A heat index this high was reached when extreme humidity hit high temperatures so people were dying who couldn't get into air conditioning or put some ice on their foreheads, the backs of their necks or wrist arteries on the inside of their forearms.

By the way 150 degrees Fahrenheit is 65.5 degrees Celsius approximately.

Why am I preparing for 150 degrees Fahrenheit? Temperatures with a heat index of 165 to 170 degrees already occurred in Pakistan and India last summer and are likely to do this or even increase in coming years in these locations or others as time goes on. A heat index this high was reached when extreme humidity hit high temperatures so people were dying who couldn't get into air conditioning or put some ice on their foreheads, the backs of their necks or wrist arteries on the inside of their forearms.

By the way 150 degrees Fahrenheit is 65.5 degrees Celsius approximately.

Latin American mercenaries, bankrolled by United Arab Emirates, join Yemen ...

| Fox News | - Nov 27, 2015 |

The exact mission of the mercenaries in Yemen

is still unclear, and it could be weeks before they see actual combat,

but the troops have joined with Sudanese soldiers recruited by Saudi

Arabia to fight in the coalition against the Iranian-backed Houthi ...

MORE FROM FOX NEWS LATINO

Latin American mercenaries, bankrolled by United Arab Emirates, join Yemen proxy war

-

Fighters loyal to Yemen's President Abedrabbo Mansour Hadi keep watch at a military area in Taez's Misrakh District on November 26, 2015. Government forces backed by air and ground support from a Saudi-led coalition last week launched a major offensive aimed at driving the Huthi Shiite insurgents out of Taez. AFP PHOTO / AHMAD AL-BASHA / AFP / AHMED al-BASHA (Photo credit should read AHMED AL-BASHA/AFP/Getty Images)

In a program launched by Blackwater founder Erik Prince and now run by the Emirati military, the force of 450 Latin American troops – mostly made up of Colombian fighters, but also including Chileans, Panamanians and Salvadorans – adds a new and surprising element to the already chaotic mix of forces from foreign governments, armed tribes, terrorist networks and Yemeni militias that are currently embroiled in the Middle Eastern nation.

It is also an insight into how many wealthy Arab nations could wage their wars in the near future – especially in places like Yemen, Libya and Syria – as they deal with standing militaries unused to long-term, sustained warfare and populations that for the most part have little interest in military service.

"Mercenaries are an attractive option for rich countries that wish to wage war yet whose citizens may not want to fight," Sean McFate, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and author of "The Modern Mercenary," told the New York Times

He added: "The private military industry is global now," adding that the U.S. "legitimized" the industry with its heavy reliance on contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan over more than a decade of war in those countries. "Latin American mercenaries are a sign of what’s to come."

The most recent group of Latin American soldiers to land in Yemen came from the ranks of about 1,800 currently training in the desert

The exact mission of the mercenaries in Yemen is still unclear, and it could be weeks before they see actual combat, but the troops have joined with Sudanese soldiers recruited by Saudi Arabia to fight in the coalition against the Iranian-backed Houthi Shiite rebels.

The use of mercenaries was originally proposed for domestic missions in the U.A.E., like guarding pipelines and possibly as crowd control in riots that break out in the camps housing foreign workers. Their deployment to Yemen is currently the only external mission such troops have been given besides providing security on commercial cargo vessels.

Emirati officials wanted Colombian mercenaries above those from other countries because they felt that they are the most battle-tested given Colombia’s long-running conflict with leftist guerrilla groups like the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN).

Most of the recruiting of former Colombian troops is being done by Global Enterprises, a Colombian company run by a former special operations commander named Oscar García Batte, who is also co-commander of the brigade of Colombian troops in the Emirates.

The troops are recruited by the promise of higher wages than they could make in Colombia. The Emirati troops earn salaries ranging from $2,000 to $3,000 a month, compared with approximately $400 a month soldiers in Colombia receive, and those who deploy to Yemen will receive an additional $1,000 a week.

Emirati officials have also doled out millions of dollars to equip the unit with firearms and armored vehicles, as well as communications systems and night-vision technology.

"These great offers, with good salaries and insurance, got the attention of our best soldiers," Jaime Ruíz, the president of Colombia’s Association of Retired Armed Forces Officials, told the Times.

end quote from:

Latin American mercenaries, bankrolled by United Arab Emirates, join Yemen ...

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)