The last glacial period, popularly known as the Ice Age was the most recent glacial period within the current ice age occurring during the last one hundred thousand ...

Last glacial period

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For the most recent period cooler than present but without significant glaciation, see

Little Ice Age.

"The Ice Age" redirects here. For the generic geological period of temperature reduction, see

Ice age.

"Last glacial" redirects here. For the period of maximum glacier extent during this time, see

Last Glacial Maximum.

The

last glacial period, popularly known as the

Ice Age was the most recent

glacial period within the

current ice age occurring during the last one hundred thousand years of the

Pleistocene, from approximately 110,000 to 12,000 years ago.

[1]

Scientists consider this "ice age" to be merely the latest glaciation

event in a much larger ice age, one that dates back over two million

years and has seen multiple glaciations.

During this period, there were several changes between glacier advance and retreat. The

maximum extent of

glaciation

within this last glacial period was approximately 22,000 years ago.

While the general pattern of global cooling and glacier advance was

similar, local differences in the development of glacier advance and

retreat makes it difficult to compare the details from continent to

continent (see picture of ice core data below for differences).

From the point of view of human

archaeology, it falls in the

Paleolithic and

Mesolithic periods. When the glaciation event started,

Homo sapiens was confined to

Africa and used tools comparable to those used by

Neanderthals in

Europe and the

Levant and by

Homo erectus in

Asia. Near the end of the event,

Homo sapiens spread into Europe, Asia, and

Australia. The retreat of the glaciers allowed groups of Asians to migrate to the

Americas and populate them.

An artist's impression of the last glacial period at glacial maximum.

[2]

Origin and definition

The last glacial period is sometimes colloquially referred to as the "last ice age", though this use is incorrect because an

ice age is a longer period of cold temperature in which

ice sheets cover large parts of the Earth, such as

Antarctica. Glacials, on the other hand, refer to colder phases within an ice age that separate

interglacials.

Thus, the end of the last glacial period is not the end of the last ice

age. The end of the last glacial period was about 10,500 BCE, while the

end of the last ice age has not yet come: little evidence points to a

stop of the glacial-interglacial cycle of the last million years.

The last glacial period is the best-known part of the current ice age, and has been intensively studied in

North America,

northern Eurasia, the

Himalaya

and other formerly glaciated regions around the world. The glaciations

that occurred during this glacial period covered many areas, mainly in

the

Northern Hemisphere and to a lesser extent in the

Southern Hemisphere. They have different names, historically developed and depending on their geographic distributions:

Fraser (in the

Pacific Cordillera of North America),

Pinedale (in the

Central Rocky Mountains),

Wisconsinan or

Wisconsin (in central North America),

Devensian (in the

British Isles),

Midlandian (in

Ireland),

Würm (in the

Alps),

Mérida (in

Venezuela),

Weichselian or

Vistulian (in

Northern Europe and northern

Central Europe),

Valdai in

Eastern Europe and

Zyryanka in

Siberia,

Llanquihue in

Chile, and

Otira in

New Zealand. The geochronological

Late Pleistocene comprises the late glacial (Weichselian) and the immediately preceding

penultimate interglacial (Eemian) preiond.

Overview

The last glaciation centered on the huge ice sheets of North America

and Eurasia. Considerable areas in the Alps, the Himalaya and the Andes

were ice-covered, and Antarctica remained glaciated.

Canada was nearly completely covered by ice, as well as the northern part of the United States, both blanketed by the huge

Laurentide ice sheet. Alaska remained mostly ice free due to

arid climate conditions. Local glaciations existed in the

Rocky Mountains and the

Cordilleran ice sheet and as

ice fields and

ice caps in the

Sierra Nevada in northern California.

[3] In

Britain, mainland

Europe, and northwestern

Asia, the

Scandinavian ice sheet once again reached the northern parts of the British Isles,

Germany,

Poland, and

Russia, extending as far east as the

Taimyr Peninsula in western Siberia.

[4] The maximum extent of western Siberian glaciation was reached approximately 16,000 to 15,000

BCE and thus later than in Europe (20,000–16,000 BCE).

[5] Northeastern Siberia was not covered by a continental-scale ice sheet.

[6]

Instead, large, but restricted, icefield complexes covered mountain

ranges within northeast Siberia, including the Kamchatka-Koryak

Mountains.

[7][8]

The

Arctic Ocean

between the huge ice sheets of America and Eurasia was not frozen

throughout, but like today probably was only covered by relatively

shallow ice, subject to seasonal changes and riddled with

icebergs calving from the surrounding ice sheets. According to the sediment composition retrieved from deep-sea

cores there must even have been times of seasonally open waters.

[9]

Outside the main ice sheets, widespread glaciation occurred on the

Alps-

Himalaya

mountain chain. In contrast to the earlier glacial stages, the Würm

glaciation was composed of smaller ice caps and mostly confined to

valley glaciers, sending glacial lobes into the Alpine

foreland. To the east the

Caucasus and the mountains of

Turkey and

Iran were capped by local ice fields or small ice sheets.

[10] In the

Himalaya and the

Tibetan Plateau, glaciers advanced considerably, particularly between 45,000–25,000 BCE,

[11] but these datings are controversial.

[12][13] The formation of a contiguous ice sheet on the Tibetan Plateau

[14][15] is controversial.

[16]

Other areas of the Northern Hemisphere did not bear extensive ice sheets, but local glaciers in high areas. Parts of

Taiwan, for example, were repeatedly glaciated between 42,250 and 8,680 BCE

[17] as well as the

Japanese Alps. In both areas maximum glacier advance occurred between 58,000 and 28,000 BCE

[18] (starting roughly during the

Toba catastrophe). To a still lesser extent glaciers existed in Africa, for example in the

High Atlas, the mountains of

Morocco, the

Mount Atakor massif in southern

Algeria, and several mountains in

Ethiopia. In the Southern Hemisphere, an ice cap of several hundred square kilometers was present on the east African mountains in the

Kilimanjaro Massif,

Mount Kenya and the

Ruwenzori Mountains, still bearing remnants of glaciers today.

[19]

Glaciation of the Southern Hemisphere was less extensive because of current configuration of continents.

Ice sheets existed in the Andes (

Patagonian Ice Sheet), where six glacier advances between 31,500 and 11,900 BCE in the Chilean Andes have been reported.

[20] Antarctica

was entirely glaciated, much like today, but the ice sheet left no

uncovered area. In mainland Australia only a very small area in the

vicinity of

Mount Kosciuszko was glaciated, whereas in

Tasmania glaciation was more widespread.

[21] An ice sheet formed in

New Zealand, covering all of the Southern Alps, where at least three glacial advances can be distinguished.

[22] Local ice caps existed in

Irian Jaya,

Indonesia, where in three ice areas remnants of the Pleistocene glaciers are still preserved today.

[23]

Named local glaciations

Antarctica glaciation

During the last glacial period

Antarctica

was blanketed by a massive ice sheet, much as it is today. The ice

covered all land areas and extended into the ocean onto the middle and

outer continental shelf.

[24][25] According to ice modelling, ice over central

East Antarctica was generally thinner than today.

[26]

Europe

Devensian & Midlandian glaciation (Britain and Ireland)

The name

Devensian glaciation is used by British

geologists and

archaeologists and refers to what is often popularly meant by the latest

Ice Age. Irish

geologists,

geographers, and

archaeologists refer to the

Midlandian glaciation as its effects in

Ireland are largely visible in the

Irish Midlands. The name Devensian is derived from the

Latin Dēvenses, people living by the

Dee (

Dēva in Latin), a river on the Welsh border near which deposits from the period are particularly well represented.

[27]

The effects of this glaciation can be seen in many geological features of

England,

Wales,

Scotland, and

Northern Ireland. Its deposits have been found overlying material from the preceding

Ipswichian Stage and lying beneath those from the following

Flandrian stage of the

Holocene.

The latter part of the Devensian includes

Pollen zones I-IV, the

Allerød and

Bølling Oscillations, and the

Older and

Younger Dryas climatic stages.

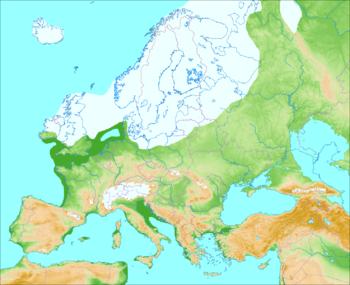

Weichselian glaciation (Scandinavia and northern Europe)

Europe during the last glacial period

Alternative names include:

Weichsel glaciation or

Vistulian glaciation (referring to the Polish river

Vistula or its German name Weichsel). Evidence suggests that the ice sheets were at their

maximum size for only a short period, between 25,000 to 13,000

BP. Eight

interstadials

have been recognized in the Weichselian, including: the Oerel, Glinde,

Moershoofd, Hengelo and Denekamp; however correlation with

isotope stages is still in process.

[28][29] During the

glacial maximum in Scandinavia, only the western parts of

Jutland were ice-free, and a large part of what is today the

North Sea was dry land connecting Jutland with Britain (see

Doggerland). It is also in Denmark that the only Scandinavian ice-age animals older than 13,000 BC are found.

[citation needed]

The

Baltic Sea, with its unique

brackish water,

is a result of meltwater from the Weichsel glaciation combining with

saltwater from the North Sea when the straits between Sweden and Denmark

opened. Initially, when the ice began melting about 10,300

BP, seawater filled the

isostatically depressed area, a temporary

marine incursion that geologists dub the

Yoldia Sea. Then, as

post-glacial isostatic rebound

lifted the region about 9500 BP, the deepest basin of the Baltic became

a freshwater lake, in palaeological contexts referred to as

Ancylus Lake,

which is identifiable in the freshwater fauna found in sediment cores.

The lake was filled by glacial runoff, but as worldwide sea level

continued rising, saltwater again breached the sill about 8000 BP,

forming a marine

Littorina Sea

which was followed by another freshwater phase before the present

brackish marine system was established. "At its present state of

development, the marine life of the Baltic Sea is less than about 4000

years old," Drs. Thulin and Andrushaitis remarked when reviewing these

sequences in 2003.

Overlying ice had exerted pressure on the Earth's surface. As a

result of melting ice, the land has continued to rise yearly in

Scandinavia, mostly in northern

Sweden and

Finland where the land is rising at a rate of as much as 8–9 mm per year, or 1 meter in 100 years. This is important for

archaeologists since a site that was coastal in the

Nordic Stone Age now is inland and can be dated by its relative distance from the present shore.

Würm glaciation (Alps)

Extent of Alpine glaciation during the Würm ice age. Blue: extent of the early ice ages

The term

Würm

is derived from a river in the Alpine foreland, approximately marking

the maximum glacier advance of this particular glacial period. The Alps

were where the first systematic scientific research on ice ages was

conducted by

Louis Agassiz at the beginning of the 19th century. Here the Würm glaciation of the last glacial period was intensively studied.

Pollen analysis, the statistical analyses of

microfossilized

plant pollens found in geological deposits, chronicled the dramatic

changes in the European environment during the Würm glaciation. During

the height of Würm glaciation,

c. 24,000–10,000 BP, most of western and central Europe and Eurasia was open steppe-tundra, while the Alps presented solid

ice fields and montane glaciers. Scandinavia and much of Britain were under ice.

During the Würm, the

Rhône Glacier

covered the whole western Swiss plateau, reaching today's regions of

Solothurn and Aarau. In the region of Bern it merged with the Aar

glacier. The

Rhine Glacier

is currently the subject of the most detailed studies. Glaciers of the

Reuss and the Limmat advanced sometimes as far as the Jura. Montane and

piedmont glaciers formed the land by grinding away virtually all traces

of the older Günz and Mindel glaciation, by depositing base moraines and

terminal moraines of different retraction phases and

loess

deposits, and by the pro-glacial rivers' shifting and redepositing

gravels. Beneath the surface, they had profound and lasting influence on

geothermal heat and the patterns of deep groundwater flow.

North America

Pinedale or Fraser glaciation (Rocky Mountains)

The Pinedale (central Rocky Mountains) or Fraser (Cordilleran ice sheet) glaciation was the last of the major

glaciations to appear in the

Rocky Mountains

in the United States. The Pinedale lasted from approximately 30,000 to

10,000 years ago and was at its greatest extent between 23,500 and

21,000 years ago.

[30]

This glaciation was somewhat distinct from the main Wisconsin

glaciation as it was only loosely related to the giant ice sheets and

was instead composed of mountain glaciers, merging into the

Cordilleran Ice Sheet.

[31] The Cordilleran ice sheet produced features such as

glacial Lake Missoula, which would break free from its ice dam causing the massive

Missoula floods.

USGS

Geologists estimate that the cycle of flooding and reformation of the

lake lasted an average of 55 years and that the floods occurred

approximately 40 times over the 2,000 year period between 15,000 and

13,000 years ago.

[32] Glacial lake outburst floods such as these are not uncommon today in

Iceland and other places.

Wisconsin glaciation

The

Wisconsin Glacial Episode was the last major advance of

continental glaciers in the North American

Laurentide ice sheet. At the height of glaciation the

Bering land bridge potentially permitted migration of

mammals, including

people, to North America from

Siberia.

It radically altered the geography of North America north of the

Ohio River. At the height of the Wisconsin Episode glaciation, ice covered most of

Canada, the

Upper Midwest, and

New England, as well as parts of

Montana and

Washington. On

Kelleys Island in

Lake Erie or in New York's

Central Park, the

grooves left by these glaciers can be easily observed. In southwestern Saskatchewan and southeastern Alberta a suture zone between the

Laurentide and

Cordilleran ice sheets formed the

Cypress Hills, which is the northernmost point in North America that remained south of the continental ice sheets.

The

Great Lakes

are the result of glacial scour and pooling of meltwater at the rim of

the receding ice. When the enormous mass of the continental ice sheet

retreated, the Great Lakes began gradually moving south due to isostatic

rebound of the north shore.

Niagara Falls is also a product of the glaciation, as is the course of the Ohio River, which largely supplanted the prior

Teays River.

With the assistance of several very broad glacial lakes, it released floods through the

gorge of the

Upper Mississippi River, which in turn was during an earlier glacial period.

In its retreat, the Wisconsin Episode glaciation left

terminal moraines that form

Long Island,

Block Island,

Cape Cod,

Nomans Land,

Martha's Vineyard,

Nantucket,

Sable Island and the

Oak Ridges Moraine in south central Ontario, Canada. In Wisconsin itself, it left the

Kettle Moraine. The

drumlins and

eskers formed at its melting edge are landmarks of the Lower

Connecticut River Valley.

Tahoe, Tenaya, and Tioga, Sierra Nevada

In the

Sierra Nevada, there are three named stages of glacial maxima (sometimes incorrectly called

ice ages) separated by warmer periods. These glacial maxima are called, from oldest to youngest,

Tahoe,

Tenaya, and

Tioga.

[33]

The Tahoe reached its maximum extent perhaps about 70,000 years ago.

Little is known about the Tenaya. The Tioga was the least severe and

last of the Wisconsin Episode. It began about 30,000 years ago, reached

its greatest advance 21,000 years ago, and ended about 10,000 years ago.

Greenland glaciation

In Northwest Greenland, ice coverage attained a very early maximum in

the last glacial period around 114,000. After this early maximum, the

ice coverage was similar to today until the end of the last glacial

period. Towards the end, glaciers readvanced once more before retreating

to their present extent.

[34]

According to ice core data, the Greenland climate was dry during the

last glacial period, precipitation reaching perhaps only 20% of today's

value.

[35]

South America

Mérida glaciation (Venezuelan Andes)

The extent of the glaciers in

Venezuelan Andes area during the last glacial period.

The name

Mérida Glaciation is proposed to designate the alpine glaciation which affected the central

Venezuelan Andes

during the Late Pleistocene. Two main moraine levels have been

recognized: one between 2600 and 2700 m, and another between 3000 and

3500 m elevation. The snow line during the last glacial advance was

lowered approximately 1200 m below the present snow line (3700 m). The

glaciated area in the

Cordillera de Mérida was approximately 600 km

2;

this included the following high areas from southwest to northeast:

Páramo de Tamá, Páramo Batallón, Páramo Los Conejos, Páramo Piedras

Blancas, and Teta de Niquitao. Approximately 200 km

2 of the total glaciated area was in the

Sierra Nevada de Mérida, and of that amount, the largest concentration, 50 km

2, was in the areas of

Pico Bolívar,

Pico Humboldt (4,942 m), and

Pico Bonpland

(4,893 m). Radiocarbon dating indicates that the moraines are older

than 10,000 years B.P., and probably older than 13,000 years B.P. The

lower moraine level probably corresponds to the main Wisconsin glacial

advance. The upper level probably represents the last glacial advance

(Late Wisconsin).

[36][37][38][39]

Llanquihue glaciation (Southern Andes)

The Llanquihue glaciation takes its name from

Llanquihue Lake in

southern Chile which is a fan-shaped

piedmont glacial lake.

On the lake's western shores there are large moraine systems of which

the innermost belong to the last glacial period. Llanquihue Lake's

varves are a node point in southern Chile's varve

geochronology. During the last glacial maximum the

Patagonian Ice Sheet extended over the Andes from about 35°S to

Tierra del Fuego at 55°S. The western part appears to have been very active, with wet basal conditions, while the eastern part was cold based.

Palsas seems to have developed at least in the unglaciated parts of

Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego. The area west of Llanquihue Lake was ice-free during the

LGM, and had sparsely distributed vegetation dominated by

Nothofagus.

Valdivian temperate rainforest was reduced to scattered remnants in the western side of the Andes.

[40]

Modelled maximum extent of the Antarctic ice sheet 21,000 years before present

See also

References

No comments:

Post a Comment