end quote from:

https://mashable.com/2018/07/31/fire-tornado-california-carr-fire/#TiGOY0vZ6iq8

Science

A California wildfire caused an honest-to-god fire tornado

IMAGE: NOAH BERGER/AP/REX/SHUTTERSTOCK

BY MARK KAUFMAN

BY MARK KAUFMAN

At around 7:00 p.m. PT on July 26, a towering vortex of smoke and flame spun into the California sky.

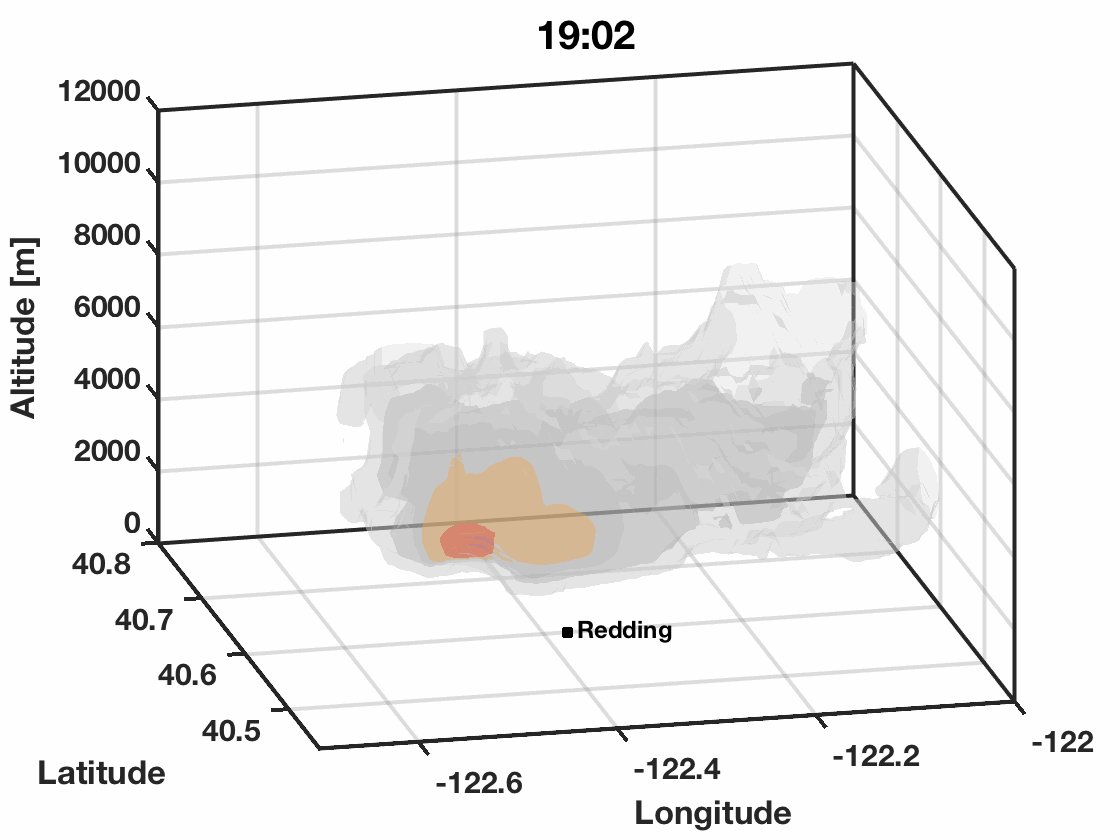

The tornado-like column rose over 16,000 feet into the air. It was a violent night for the Carr Fire, which after preying on profoundly dry forests, breached the Sacramento River and headed into the City of Redding, home to over 90,000 people.

There’s no official name for the dramatic phenomena, though “firenado” has become popular.

“I’m not particularly fond of the term,” Brenda Belongie, lead meteorologist of the U.S. Forest Service's Predictive Services in Northern California, who works and lives in Redding, said in an interview. “But it works because of the strength of the fire whirl, the size — and the destructiveness is not unlike the power of a tornado.”

The deadly Carr Fire, like many of the fires now burning across the besieged Golden State, was propelled by weather — strong gusty winds and hot temperatures — but enhanced by climate change, which has boosted summer temperatures to record or near-record temperatures around the globe and in Redding.

Dominant fire tornados, stoked by incredible heat and other ingredients, have been observed before, but not too often.

“It’s relatively rare — but it’s not an unknown phenomenon,” said Belongie, noting that substantially smaller fire whirls can often be spotted amid fires — though not imposing vortices.

“What’s really unheard of here is getting it to come down to a population center,” Neil Lareau, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Nevada, Reno who studies wildfire plume dynamics, said in an interview. "Almost every fire has some sort of small whirl."

How did the firenado form?

Not every fire has the benefit of burning over grasses, shrubs, and trees — collectively known as fuels — that have been dried-out by extreme heat.

#CarrFire tornado zone. Complete devastation. That’s a steel pipe wrapped around a tree. #CAfire #CAWx pic.twitter.com/IBWGXOXlNt— SJSU FireWeatherLab (@FireWeatherLab) July 31, 2018

"You have an extreme event in terms of July probably being the hottest July in northern Sacramento Valley on record," said Lareau. That further drives down the moisture in the fuels, he noted, making the land more combustible.

"All that energy can be converted into heat," said Lareau, which can then rise into the air at speeds of 130 mph. "This is the mechanism driving these vortices."

The rising air forces the vortex to stretch upward, and spin faster.

"It's the ice skater effect," said Belongie, noting how ice skaters pull their arms in to whirl faster. "It's the same physics."

But unlike tornados, which typically form during thunderstorms, these firenados start on the ground level. The sources of the initial spin are "countless," said Lareau. The fire tornados could be kicked off by whipping winds interacting with unique terrain and topography, or a spin enabled by the heat itself.

Either way, if a small whirl is stoked into a towering firenado, it promptly becomes unpredictable. It's a spinning storm.

"It’s notoriously difficult to predict what they're going to do because they’re creating they’re own weather," said Lareau.

"You’re not sure where the vortex is going to go — it can wander a path with no predictability," said Belongie.

During a massive fire, such a firenado can come and go.

The Carr Fire vortex lasted 80 minutes. It didn't reappear over the weekend — but it very well could have, amid a towering, violent fire, which sent an apocalyptic plume into the sky.

The brothers taking safe refuge under extreme fire conditions #carrfire

"It's like a big eddy in the whole event," said Belongie.

As of the morning of July 31 — the Carr Fire's ninth day of burning — it had spread to over 110,000 acres, destroying over 1,200 buildings and making it the seventh most destructive fire in California's history.

Less than 30 percent of the fire is contained, and it has claimed six lives.

A bright light, amid the whirling flames, leveled homes, and smoke-choked air, are the citizens of Redding themselves.

Belongie said people are offering to help complete strangers in grocery stores, not knowing who has lost their home — or worse.

"We take care of ourselves very nicely," she said. "That's just the way we are."

/https%3A%2F%2Fblueprint-api-production.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fuploads%2Fcard%2Fimage%2F820035%2Ff335a551-4938-4ce6-888c-b4f1d1126ec2.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment