The Central Coast estate that Debbie Reynolds and Carrie Fisher loved is back on the market — and it’s priced to move

Left to right, Debbie Reynolds and daughter Carrie Fisher host a CBS television special: All-Star Moms. Image dated April 20, 1997. The program originally broadcast on Friday, May 9, 1997, two days before Mothers Day.

CBS Photo Archive/CBS via Getty ImagesThere’s a haunted image that adorns the wall of the room classic Hollywood star Debbie Reynolds stayed in when she visited her family’s Central Coast retreat. It’s an oil painting which represents a young Reynolds in clown make-up, barely smiling, staring blankly into the distance. Today, it still hangs there right next to her queen bed.

“Ain’t that something,” son Todd Fisher said to me on a recent guided tour of the property via FaceTime. “I can’t tell you why, but for some reason, it was her favorite.”

This isn’t the only piece of memorabilia from Reynolds’ life at the 44-acre compound, called Freedom Farms, now on the market for $2.85 million. The property, which includes multiple buildings and much, much more, also houses an expansive collection from Fisher’s famous family: His mother, one of the stars of “Singin’ in the Rain,” her husband, singer Eddie Fisher (who notoriously abandoned his wife for Elizabeth Taylor) and his sister, Star Wars icon Carrie Fisher.

The 44-acre ranch in Creston, Calif. owned by Todd Fisher is filled with lush meadows, fruit-producing trees, a natural lake and hot springs and a pride of peacocks.

Photo By Andrew PridgenFisher says he bought the estate from a Hollywood stunt woman in the late 1980s, intending it to be a spot to raise his young family and provide respite for his mother and sister. Over the years, he and Reynolds would become joint owners of the property.

The ranch was her sanctuary, her spot to commune with nature — and even a place to work, with a sound studio constructed for her. Following her death in 2016, Fisher became the sole owner and custodian of the property.

The Central Coast compound includes a lake and a natural hot spring, a main home, a barn and two outbuildings. The property is defined by rolling hills dotted with legacy oaks and stands of redwood, aspen and fruit trees.

Coined "Freedom Farms," the 44-acre ranch owned by Todd Fisher (son of Debbie Reynolds and brother of Carrie Fisher) has recently been listed for $2.85 million.

Photo By Andrew PridgenThere’s a burro who “answers to nobody,” Fisher says, though the donkey does spend his days getting mocked by the many families of ducks and geese who patrol the area. All of the wildlife on the premises, including multiple generations of deer, raccoons and kit foxes, seem to fall in line under a rogue flock of aggressive peacocks. The birds even keep the coyotes at bay. And because the ranch is tucked away from view in a canyon, there’s a natural breeze that comes right through, seemingly on the hour, every hour.

Along with the main home and the barn, there’s a pair of yellow-hued warehouses, complete with cement helicopter pad and loading docs. These buildings include more than 17,000 square feet of storage, Reynolds’ sound stage, a recording studio and offices. Inside, that’s where you’ll find seemingly every inch filled with artifacts from the storied careers of Reynolds, Eddie, and Carrie.

‘There’s just a lot of history’

Freedom Farms is plunked in a tiny town called Creston (not to be confused with Creston, another village in Napa County), nestled in the middle of a hidden valley, rife with horse ranches and active vineyards. The area has no discernible landmarks, services or town center, beyond the refurbished general store which sells locally produced wines, cheeses and fruits — along with what I’m told is a mean cheesesteak.

One of two warehouses at Todd Fisher's Creston, Calif. property holds an immense storage area, as well as offices, a recording studio and a sound studio.

Photo By Andrew PridgenFar off the beaten path, Creston is 205 miles northwest of Los Angeles, 218 miles south of San Francisco and 25 miles northeast of San Luis Obispo. It’s a town for people who want to hide away.

Film cannisters, containing thousands of hours of footage from the golden age of Hollywood footage, stored at Todd Fisher's Creston, Calif. ranch.

Photo By Andrew Pridgen“We’ve seen a lot of out-of-town activity in places like this that previously went overlooked,” says Jen Kennedy of Sotheby’s International, the real estate agent who represents Fisher in the sale. “If people want privacy and want land, this is the place — and people can get in now before it gets too saturated here.

“Plus, with the Fisher property — there’s just a lot of history. You feel it as soon as you arrive.”

She’s right. There’s something different about the spread that’s evident from the moment you arrive. There’s a hum of wildlife activity, combined with the weight of history: decades’ worth of the family’s tales — music, laughter, heartbreak, tears and rehab.

A wall of fame featuring Debbie Reynolds overseeing the activity of her children, Carrie and Todd Fisher.

Photo By Andrew PridgenThis isn’t the first time the property has been on the market in recent years, However. Fisher says he put the property up for sale in 2017, for the first of three tries after his mother and sister died in December 2016. The ranch has been in escrow twice. Thus far, he says, it just hasn’t found the right buyer, though now he feels the time is right and a sale is imminent.

“We never priced it so aggressively,” he says. “We’re just not using it like we did, and it’s just insane to have something that valuable just sit.”

Every room, every photo, every artifact in the place holds some special meaning. It’s overwhelming — and not just in scope and scale. The story that accompanies each piece contains multitudes. It’s difficult to pause at a single throw rug, painting or end table and not want to sit there and unpack it for hours.

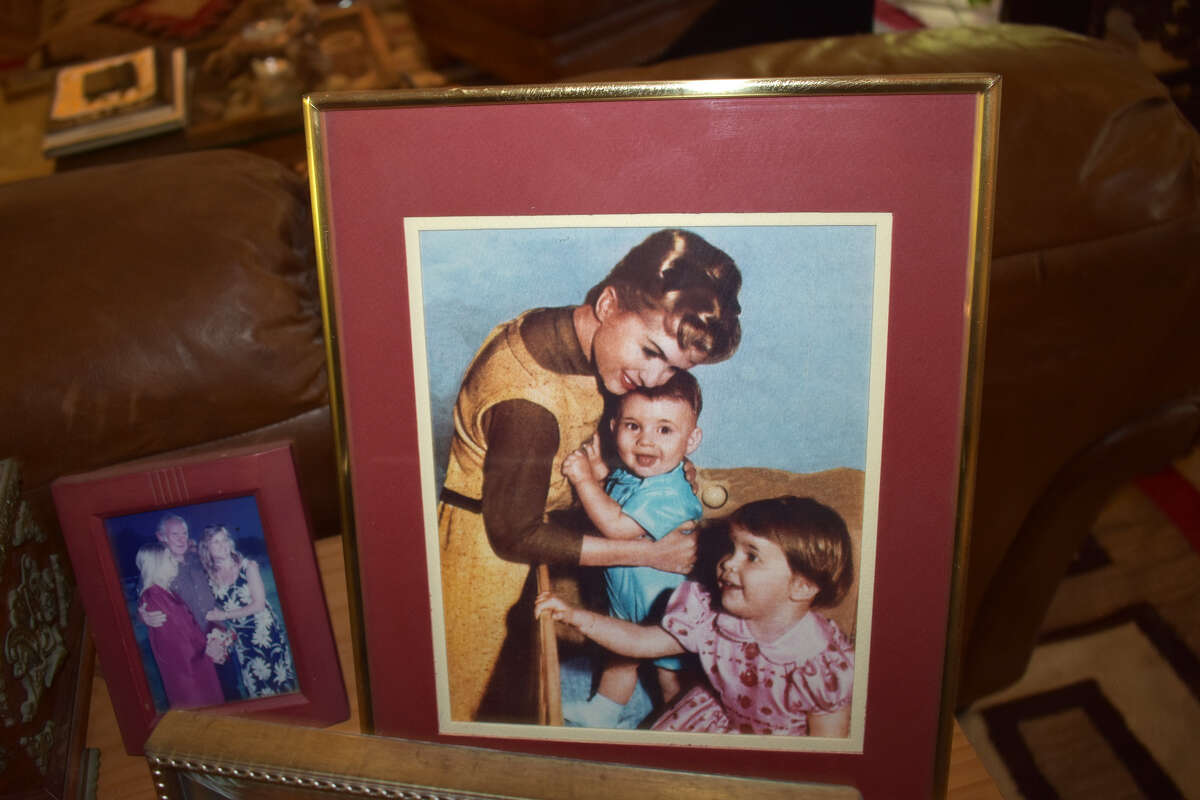

Debbie Reynolds with her children, Carrie and Todd Fisher, after father Eddie Fisher left the family to marry Debbie's best friend, Elizabeth Taylor, when Todd was only three months old.

Photo By Andrew Pridgen“As Carrie used to say, our family wears its underwear on the outside; we decided a long time ago to be an open book,” Fisher told me, “so I’m just continuing in our little tradition. And I am the last one to tell you about it.”

A temple to the Golden Age of Hollywood

When you first walk into the main home, you can’t help but hear the voices from beyond. There, perched on a solid oak platform as soon as you set foot through the door, is a grand piano. It’s the same one, Fisher says, that accompanied Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett and Dean Martin — and, of course, Reynolds herself, at the long-defunct hotel and casino Debbie Reynolds’ Hollywood Hotel, just off the Strip in Las Vegas.

Sinatra, and a whole lot of other folks, sang here. Visitors to the Reynolds-Fisher family ranch in Creston, Calif. were greeted with the same piano that the great crooners of yore sang at while performing at Debbie Reynolds' Las Vegas showroom and casino.

Photo By Andrew PridgenFisher noted that not only did the great crooners of yore lean upon the matte black instrument, it also served its purpose at many a family get-together; impromptu sing-a-longs that lasted deep into the night.

“We were always a musical family,” he said. "So at some point during every holiday, at every gathering, someone would sit down and start going. Of course, Carrie was the harshest critic.”

Built in 1991, the house, which is a seemingly vast 7,800 square feet, still feels cozy and cluttered. It’s decorated with a hodgepodge of golden-age Hollywood posters, original art, family heirlooms and photos. Nearly every spot on the wall, every space on the floor and every forgotten ledge and blind corner is spoken for; heaping amounts of tchotchkes, movie studio props and thrift store finds are spotted at every angle. There is no single era represented or a cordoned off space to honor a specific artifact. Instead it’s a flowing, story-worthy kind of space.

A mural of Hollywood greats treated visitors who entered Debbie Reynolds' Hollywood Hotel, once open off the Strip in Las Vegas. The mural is now part of the offices situated on a 44-acre ranch in Creston, Calif., recently listed for $2.85 million.

Photo By Andrew PridgenAnd the right buyer may get to keep some of what’s there, Fisher says.

“There certainly is some memorabilia that I would be fine parting with,” he told me. “Certain furniture or certain artwork that I would be fine with leaving, that’s all negotiable. But there’s also things that don’t fit that bill. There’s some rare stuff on the walls, some really high-end photography, and some family things. But, if the right person shows the right — let’s just say concern and care — and I felt that they were going to look after something, I wouldn’t have any problem because that’s what Debbie wanted. She wanted to share some of that with her fans. And our storage room is bursting at the seams.”

Rows and rows of clothes that belonged to golden-age Hollywood great Debbie Reynolds are still stored in the family's Creston, Calif. ranch.

Photo By Andrew PridgenIndeed, there is a lot. And every step, every decade is loosely chronicled. Near the front door is the entry table that greeted visitors at Debbie and Eddie’s salad days at their Beverly Hills home. Across the room, a flag from the American Revolution hangs, framed on the wall — a wedding present from Paul Simon after he and Carrie married. At the top of the stairs is a glowering portrait of Debbie, used in the 2013 HBO Liberace biopic “Behind the Candelabra.” Adjacent to that, a photo wall goes back to Debbie’s high school picture, taken just before she was crowned Miss Burbank at age 16 in 1948.

The rise of a storied Hollywood family

Reynolds’ career started the day she was awarded the beauty contest’s top prize of a sweater and a screen test, which she managed to parlay into a seven-year contract with Warner Brothers. At the time, LA superior court judge Clarence M. Hansen mandated she invest 20% of the deal into government bonds.

A young Debbie Reynolds poses with her parents.

Photo By Andrew PridgenFrom there, it only took four years for Reynolds to go from JCPenney shop girl and high school co-ed to a career-defining turn as the female lead in MGM’s song-and-dance showcase “Singin’ in the Rain,” alongside Gene Kelly and Donald O’Connor.

The musical, which fancifully chronicled Hollywood’s transition from silent films to talkies, featured Reynolds as the girl next door, a fresh face that transcended the medium, finding her way into the hearts of her male leads and worldwide audiences.

Reynolds’ sudden emergence into the Hollywood elite continued, reaching a zenith with her marriage to crooner heartthrob Eddie Fisher in 1955. America could hardly get enough of its most photogenic couple and their two children, Carrie (b. 1956) and Todd (b. 1958).

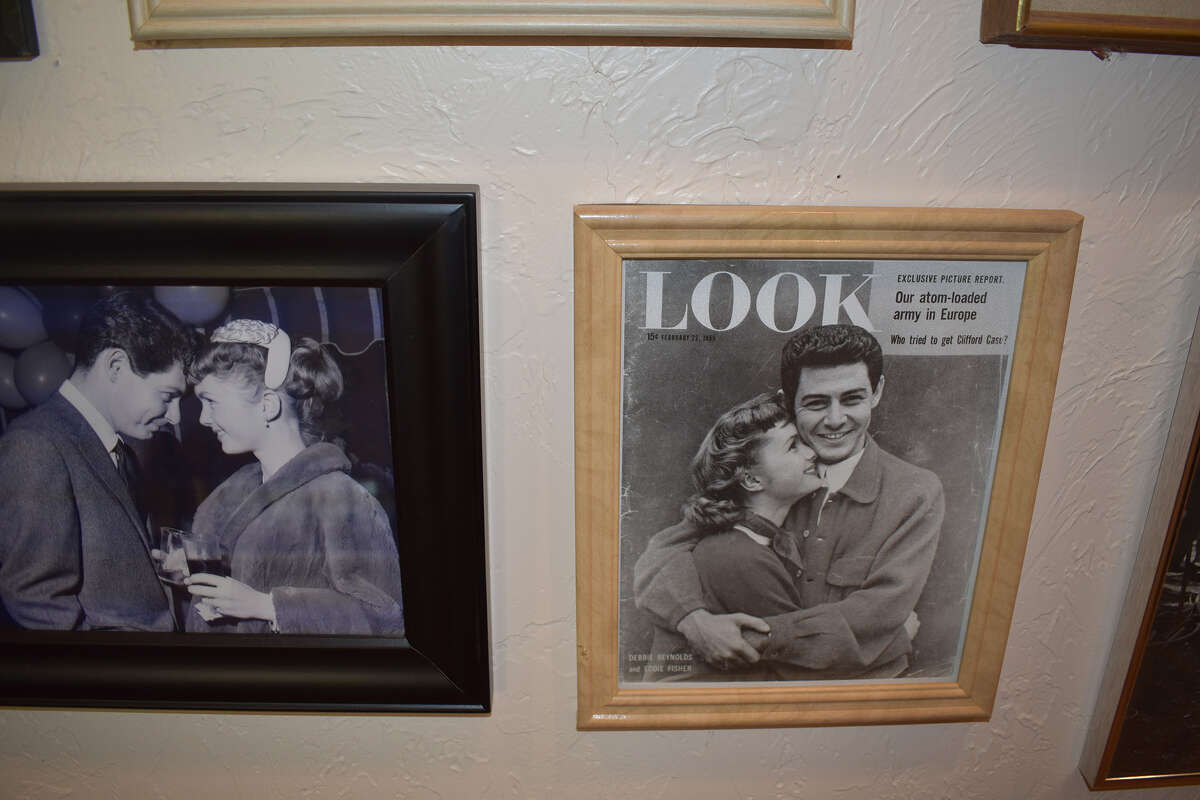

A picture and magazine cover of the courtship of Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher hangs in the hallway of son Todd Fisher's 44-acre ranch in Creston, Calif.

Photo By Andrew PridgenBut scandal defined the young family from the moment Fisher divorced Reynolds, shortly after Todd was born, to take up with Liz Taylor — Reynolds’ best friend — soon after Taylor’s third husband Mike Todd was killed in a plane crash. Eddie “basically fled the scene of the accident,” Carrie once said of her parents’ quickly dissolved marriage, later mentioning that she “saw him more on TV than on the planet.”

When we stumbled upon a black-and-white picture of Eddie, holding Carrie in one arm and a three-month-old Todd in the other, tucked in a corner, Fisher inhaled and said, “Yeah, that’s probably the last photo before Eddie left.”

‘The magic never faded’

Fisher turned his attention to an ample home theater room, where Debbie and Carrie would retreat to sip some wine and watch one of more than 5,000 classic titles — original prints, VHS, laser disc, DVDs — stored in the projection area behind the back row.

As with many parts of Todd Fisher's Creston, Calif.-based ranch, the entryway features a vintage movie poster, along with an entry table that used to greet visitors at the Beverly Hills home of his parents, Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher.

Photo By Andrew PridgenHis family was not just in the movies, Fisher said, but ultimately, fans of them. “Somehow, even though we all lived behind the scenes, the magic never faded,” he said.

Reynolds, one of the first and now the most noteworthy collectors of Hollywood memorabilia, started accumulating in earnest in 1970, when she spent $180,000 at an MGM auction buying several notable items, including the ruby slippers from “The Wizard of Oz.” Her collection grew to become the largest privately held cache of Hollywood treasures in the world — at one point, she had more than 3,000 costumes, with at least one from each film nominated for Costume Design or Best Production Design.

Carrie also inherited the collecting gene. She was regularly found at Central Coast thrift shops, and the Saturday swap meet at the San Luis Obispo’s Sunset Drive-in. But while Carrie was addicted to finding Tiffany Lamps at a discount, Debbie was solely focused on Hollywood, which included an emphasis on curating her and her family’s own body of work, Todd Fisher says.

Carrie Fisher in her famed "Return of the Jedi" bikini on the beach Golden Gate National Recreation Area, Calif.

Aaron Rapoport/Corbis via Getty ImagesHe remembered when Debbie rescued Carrie’s old diaries from the garbage in front of Carrie’s home in Beverly Hills; the pair were next-door neighbors and often Reynolds would “dumpster dive” in her daughter’s trash, Fisher said.

“Carrie was a collector, but everything of hers she threw away, and Debbie knew it, so she rescued what she could,” Fisher recalled. Many of Carrie’s discards ended up in boxes with Debbie’s handwritten “Ranch” in a flourish on it. The boxes were then stored in Creston, including the journals that inspired Fisher’s last book, “The Princess Diarist,” a 2016 memoir chronicling her initial turn as Princess Leia at only 19.

“Debbie wanted it all — to keep and preserve,” Fisher says, “While Carrie, whose final addiction ...to shopping, meant that she was constantly buying things for people and giving them away. She was the one on Christmas morning with a pile of presents at the end — she’d spent the whole time handing [gifts] out to other people.”

How the Academy of Motion Picture Arts snubbed Debbie Reynolds five times

Reynolds had pleaded with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts to take her holdings for decades. She was turned down five times, and the Creston ranch warehouses stored the vast majority of her artifacts. Finally, facing financial difficulties in the early 2010s, Reynolds sold some of her more notable items at three auctions that took place from 2011 to 2014.

Miles and miles and miles of film are sitting in the Creston, Calif. ranch owned by Todd Fisher. From original prints to never-seen-family footage of mother Debbie Reynolds and sister Carrie, part of Fisher's daily routine is to catalog and archive what has been stored at the ranch for decades.

Photo By Andrew PridgenThe artifacts sold included Marilyn Monroe’s famous white halter dress (the one that billowed over a street grate in "The Seven Year Itch") which fetched $4.6 million. Audrey Hepburn’s Royal Ascot dress from “My Fair Lady” took in $3.7 million. The outsized interest and intense bidding surprised even the most jaded memorabilia collectors, re-setting the market and proving Reynolds’ hunch to accumulate and preserve to be the right one.

Yet even at auction, and despite the millions the items brought in, Reynolds still was not rewarded with recognition from the academy she so desired.

“Debbie sat on my sofa and cried when she had to sell,” Deborah Nadoolman Landis, founding director of the David C. Copley Center for Costume Design at the University of California, Los Angeles, told the New York Times. “The academy bought nothing. It was a tragedy.”

Carrie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds attend "The Unsinkable Molly Brown" Opening on September 19, 1989 at the Pantages Theater in Hollywood, California.

Ron Galella/Ron Galella Collection via Getty“I think it was institutionalized sexism,” Landis said of the snub. With costume design credits on “Raiders of the Lost Ark” and “Coming to America,” she had been a member of the Academy since 1988. “Our field was considered women’s work and treated with disrespect.”

The rest of the family’s Hollywood memorabilia collection went to Fisher after his sister and mother died within 24 hours of each other. Today, along with writing, directing and producing — he was the producer on 2016’s acclaimed HBO documentary “Bright Lights: Starring Carrie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds” — Fisher keeps close watch over the physical estate which has been relocated, one piece, one box at a time, from the Creston property to his home and storage facilities in Henderson.

Each morning, Fisher says he starts his day with three hours of organizing: going through the archives, cataloging and curating. It’s a labor of love, but one he admits “can be draining” — both in time and energy. Even unpacking a single box can eat up half a day, he says.

One of Debbie Reynolds' robes displayed on the bed she slept in while staying at her family's 44-acre Central Coast ranch in Creston, Calif.

Photo By Andrew PridgenBut the payoff is real, as recognition of and interest in the family’s artifacts continues to rise. Four years after Debbie and Carrie’s deaths, the new Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, located in the heart of Hollywood on Wilshire Boulevard, came calling.

“I approached Todd about a year ago with the idea of naming our museum’s conservation studio after his mother, who was so key to our history, not only as an artist — acting, dancing, singing, her comedy — but also as a collector and preservationist,” museum director Bill Kramer told the New York Times. “It turned into a conversation about how we might be able to work with Todd and the collection to bring Debbie’s legacy — and Todd’s and Carrie’s — into the museum in a tangible way.”

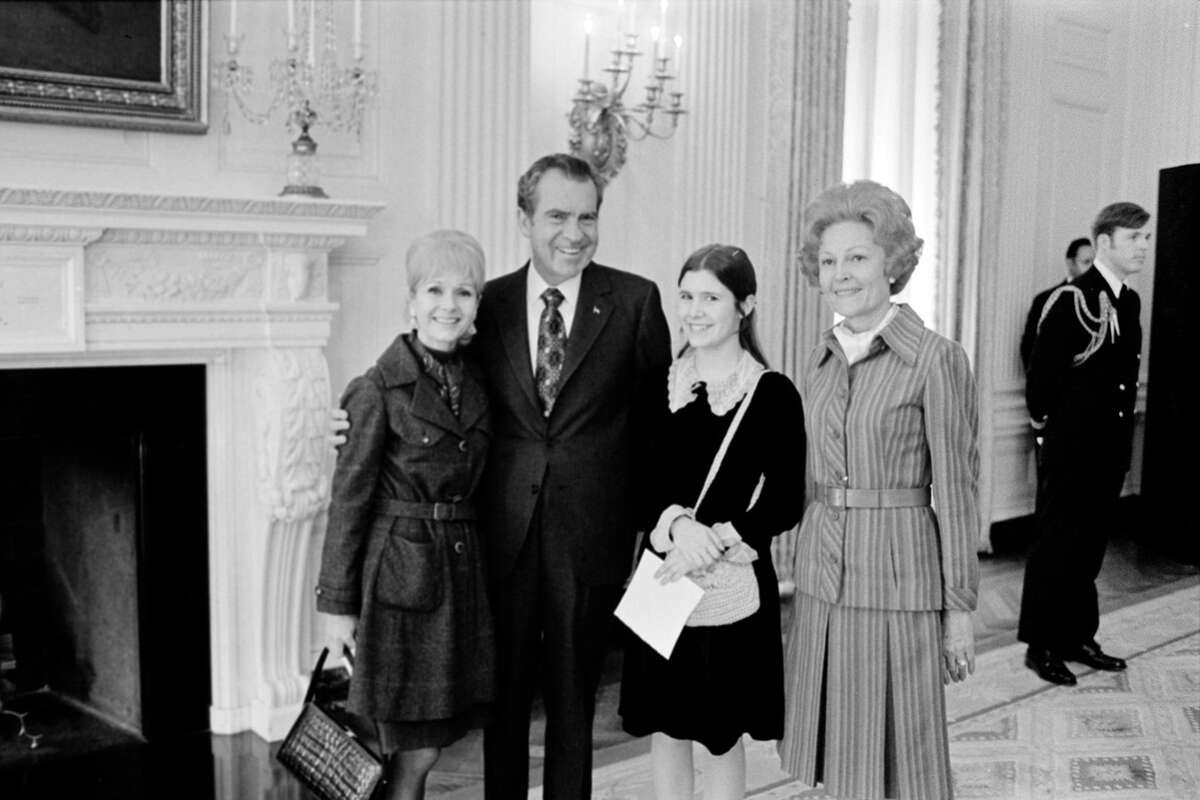

Group portrait of, from left, American actress Debbie Reynolds (1932 - 2016), US President Richard Nixon (1913 - 1994), Reynolds' daughter, actress Carrie Fisher (1956 - 2016), and First Lady Pat Nixon (1912 - 1993) as they pose togather in the White House, Washington DC, February 10, 1974.

PhotoQuest/Getty ImagesFisher has dipped into his collection only to lend the museum a set of seven Bausch and Lomb Baltar lenses, used by Gregg Toland, the cinematographer for “Citizen Kane.” He is still “working out” the fate of the family’s vast holdings, and how to do so in a way that “best honors” the legacy of his mother, sister — and his father.

A place to ‘reel in the sanity’

As he continues to up his role in the ongoing preservation effort, Fisher still has projects of his own in the queue as well. A recent conversation found him in Laguna Beach, on the set of a reality TV series he’s shooting featuring NFL great Emmitt Smith. As Fisher continues to work and curate, he notes the family legacy is also entering a new chapter, one that will include a significant downsizing, as represented by the listing of the Creston property.

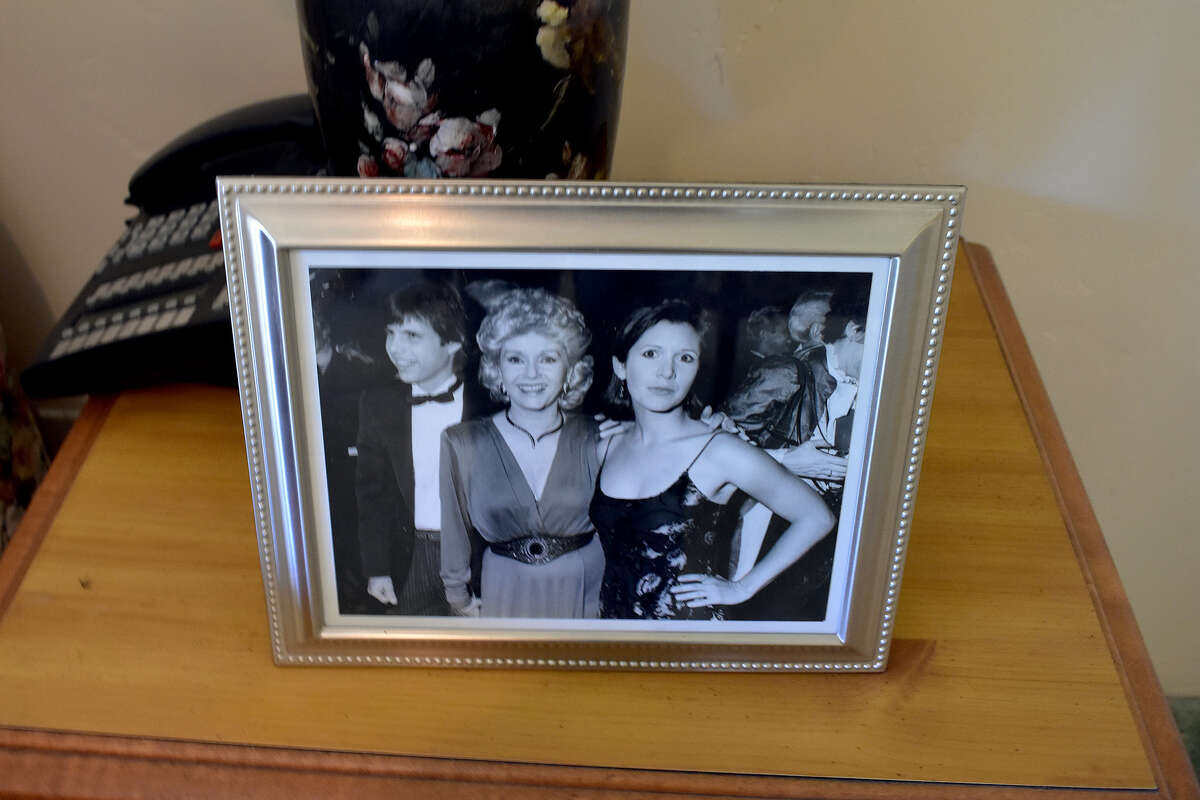

Debbie Reynolds flanked by children Todd and Carrie Fisher.

Photo By Andrew Pridgen“I can put it this way: my mother being the patriarch of the family really set the tone,” he said. “There was always entertaining and always storytelling. After a few glasses of wine, we could get brutally honest. But these things are a part of our past, as the ranch is a part of our past … My job is to protect what needs protecting, and that includes my memories: I remember Carrie writing in her room there, and sometimes as many as 50 deer coming to visit my mother in the morning.

A young Carrie Fisher looks at all that's to come. This picture, and thousands like it chronicling the lives of Debbie Reynolds and her children Carrie and Todd Fisher, can be found at the family's Creston, Calif. ranch, recently listed for $2.85 million.

Photo By Andrew Pridgen“These were two of the world’s most famous people, even as honest, as forthcoming, as they were they knew they had to wear a mask in public. …But here, at the ranch, that mask came off. It was a place to reel in the sanity.”

No comments:

Post a Comment