BEGIN QUOTE FROM:

Wessex - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wessex

Wessex was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom in the south of Great Britain, from 519 until England was unified by Æthelstan in the early 10th century. The Anglo-Saxons believed that Wessex was founded by Cerdic and Cynric, but this may be a legend. The two main sources for the history of Wessex are the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle ...As a result of the Mercian conquest of the northern portion of its early territories in Gloucestershire and Oxfordshire, the Thames and the Avon now probably formed the northern boundary of Wessex, while its heartland lay in Hampshire, Wiltshire, Berkshire, Dorset and Somerset. The system of shires which was later to form the basis of local administration throughout England (and eventually, Ireland, Wales and Scotland as well) originated in Wessex, and had been established by the mid-8th century.

Hegemony of Wessex and the Viking raids[edit]

In 802 the fortunes of Wessex were transformed by the accession of Egbert who came from a cadet branch of the ruling dynasty that claimed descent from Ine's brother Ingild. With his accession the throne became firmly established in the hands of a single lineage. Early in his reign he conducted two campaigns against the "West Welsh", first in 813 and then again at Gafulford in 825. During the course of these campaigns he conquered the western Britons still in Devon and reduced those beyond the River Tamar, now Cornwall, to the status of a vassal.[25] In 825 or 826 he overturned the political order of England by decisively defeating King Beornwulf of Mercia at Ellendun and seizing control of Surrey, Sussex, Kent and Essex from the Mercians, while with his help East Anglia broke away from Mercian control. In 829 he conquered Mercia, driving its King Wiglaf into exile, and secured acknowledgement of his overlordship from the king of Northumbria. He thereby became the Bretwalda, or high king of Britain. This position of dominance was short-lived, as Wiglaf returned and restored Mercian independence in 830, but the expansion of Wessex across south-eastern England proved permanent.

Egbert's later years saw the beginning of Danish Viking raids on Wessex, which occurred frequently from 835 onwards. In 851 a huge Danish army, said to have been carried on 350 ships, arrived in the Thames estuary. Having defeated King Beorhtwulf of Mercia in battle, the Danes moved on to invade Wessex, but were decisively crushed by Egbert's son and successor King Æthelwulf in the exceptionally bloody Battle of Aclea. This victory postponed Danish conquests in England for fifteen years, but raids on Wessex continued.

In 855–856 Æthelwulf went on pilgrimage to Rome and his eldest surviving son Æthelbald took advantage of his absence to seize his father's throne. On his return, Æthelwulf agreed to divide the kingdom with his son to avoid bloodshed, ruling the new territories in the east while Æthelbald held the old heartland in the west. Æthelwulf was succeeded by each of his four surviving sons ruling one after another: the rebellious Æthelbald, then Æthelbert, who had previously inherited the eastern territories from his father and who reunited the kingdom on Æthelbald's death, then Æthelred, and finally Alfred the Great. This occurred because the first two brothers died in wars with the Danes without issue, while Æthelred's sons were too young to rule when their father died.

Last English kingdom[edit]

In 865, several of the Danish commanders combined their respective forces into one large army and landed in England. Over the following years, what became known as the Great Heathen Army overwhelmed the kingdoms of Northumbria and East Anglia. Then in 871, the Great Summer Army arrived from Scandinavia, to reinforce the Great Heathen Army. The reinforced army invaded Wessex and, although Æthelred and Alfred won some victories and succeeded in preventing the conquest of their kingdom, a number of defeats and heavy losses of men compelled Alfred to pay the Danes to leave Wessex.[26][27] The Danes spent the next few years subduing Mercia and some of them settled in Northumbria, but the rest returned to Wessex in 876. Alfred responded effectively and was able with little fighting to bring about their withdrawal in 877. A portion of the Danish army settled in Mercia, but at the beginning of 878 the remaining Danes mounted a winter invasion of Wessex, taking Alfred by surprise and overrunning much of the kingdom. Alfred was reduced to taking refuge with a small band of followers in the marshes of the Somerset Levels, but after a few months he was able to gather an army and defeated the Danes at the Battle of Edington, bringing about their final withdrawal from Wessex to settle in East Anglia. Simultaneous Danish raids on the north coast of France and Brittany occurred in the 870s – prior to the establishment of Normandy in 911 – and recorded Danish alliances with both Bretonsand Cornish may have resulted in the suppression of Cornish autonomy with the death by drowning of King Donyarth in 875 as recorded by the Annales Cambriae.[28] No subsequent 'Kings' of Cornwall are recorded after this time, however Asser records Cornwall as a separate kingdom from Wessex in the 890s.[29]

In 879 a Viking fleet that had assembled in the Thames estuary sailed across the channel to start a new campaign on the continent. The rampaging Viking army on the continent encouraged Alfred to protect his Kingdom of Wessex.[30] Over the following years Alfred carried out a dramatic reorganisation of the government and defences of Wessex, building warships, organising the army into two shifts which served alternately and establishing a system of fortified burhs across the kingdom. This system is recorded in a 10th-century document known as the Burghal Hidage, which details the location and garrisoning requirements of thirty-three forts, whose positioning ensured that no one in Wessex was more than a long day's ride from a place of safety.[31] In the 890s these reforms helped him to repulse the invasion of another huge Danish army – which was aided by the Danes settled in England – with minimal losses.

Alfred also reformed the administration of justice, issued a new law code and championed a revival of scholarship and education. He gathered scholars from around England and elsewhere in Europe to his court, and with their help translated a range of Latin texts into English, doing much of the work in person, and orchestrated the composition of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. As a result of these literary efforts and the political dominance of Wessex, the West Saxon dialect of this period became the standard written form of Old English for the rest of the Anglo-Saxon period and beyond.

The Danish conquests had destroyed the kingdoms of Northumbria and East Anglia and divided Mercia in half, with the Danes settling in the north-east while the south-west was left to the English king Ceolwulf, allegedly a Danish puppet. When Ceolwulf's rule came to an end he was succeeded as ruler of "English Mercia" not by another king but by a mere ealdorman named Aethelred, who acknowledged Alfred's overlordship and married his daughter Ethelfleda. The process by which this transformation of the status of Mercia took place is unknown, but it left Alfred as the only remaining English king.

Unification of England and the Earldom of Wessex[edit]

After the invasions of the 890s, Wessex and English Mercia continued to be attacked by the Danish settlers in England, and by small Danish raiding forces from overseas, but these incursions were usually defeated, while there were no further major invasions from the continent. The balance of power tipped steadily in favour of the English. In 911 Ealdorman Æthelred died, leaving his widow, Alfred's daughter Æthelflæd, in charge of Mercia. Alfred's son and successor Edward the Elder, then annexed London, Oxford and the surrounding area, probably including Middlesex, Hertfordshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire, from Mercia to Wessex. Between 913 and 918 a series of English offensives overwhelmed the Danes of Mercia and East Anglia, bringing all of England south of the Humber under Edward's power. In 918 Æthelflæd died and Edward took over direct control of Mercia, extinguishing what remained of its independence and ensuring that henceforth there would be only one Kingdom of the English. In 927 Edward's successor Athelstan conquered Northumbria, bringing the whole of England under one ruler for the first time. The Kingdom of Wessex had thus been transformed into the Kingdom of England.

Although Wessex had now effectively been subsumed into the larger kingdom which its expansion had created, like the other former kingdoms, it continued for a time to have a distinct identity which periodically found renewed political expression. After the death of King Eadred in 955, who had no legitimate heirs, the rule of England passed to his nephew, Edwig. Edwig's unpopularity with the nobility and the church led the thanes of Mercia and Northumbria to declare their allegiance to his younger brother, Edgar, in October 957, though Edwy continued to rule in Wessex. In 959, Edwy died and the whole of England came under Edgar's control.

After the conquest of England by the Danish king Cnut in 1016, he established earldoms based on the former kingdoms of Northumbria, Mercia and East Anglia, but initially administered Wessex personally. Within a few years, however, he had created an earldom of Wessex, encompassing all of England south of the Thames, for his English henchman Godwin. For almost fifty years the vastly wealthy holders of this earldom, first Godwin and then his son Harold, were the most powerful men in English politics after the king. Finally, on the death of Edward the Confessor in 1066, Harold became king, reuniting the earldom of Wessex with the crown. No new earl was appointed before the ensuing Norman Conquest of England, and as the Norman kings soon did away with the great earldoms of the late Anglo-Saxon period, 1066 marks the extinction of Wessex as a political unit.

Contemporary use of the name[edit]

From the second edition (1989) of the Oxford English Dictionary:

Symbols[edit]

Wyvern or dragon[edit]

Both Henry of Huntingdon and Matthew of Westminster talk of a golden dragon being raised at the Battle of Burford in 752 by the West Saxons. The Bayeux Tapestry depicts a fallen golden dragon, as well as a red/golden/white dragon at the death of King Harold II, who was previously Earl of Wessex. Dragon standards were in fairly wide use in Europe at the time, being derived from the draco standard employed by the later Roman army , and there is no evidence that it explicitly identified Wessex.[32]

A panel of 18th century stained glass at Exeter Cathedral indicates that an association with an image of a dragon in south west Britain pre-dated the Victorians. Nevertheless, the association with Wessex was only popularised in the 19th century, most notably through the writings of E. A. Freeman. By the time of the grant of armorial bearings by the College of Arms to Somerset County Council in 1911, a (red) dragon had become the accepted heraldic emblem of the former kingdom.[33] This precedent was followed in 1937 when Wiltshire County Council was granted arms.[34] Two gold Wessex dragons were later granted as supporters to the arms of Dorset County Council in 1950.[35]

In the British Army the wyvern has been used to represent Wessex: the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division, and postwar regional 43 (Wessex) Brigade adopted a formation sign consisting of a gold wyvern on a black or dark blue background. The regular Wessex Brigade of the 1960s adopted a cap badge featuring the heraldic beast, until the regiments took back up individual regimental badges in the late 1960s. The Territorial Army Wessex Regiment continued to wear the Wessex Brigade badge until the late 1980s when its individual companies too readopted their parent regular regimental cap badges. The now disbanded West Somerset Yeomanry adopted a Wessex Wyvern rampant as the centre piece for its cap badge, and the current Royal Wessex Yeomanryadopted a similar device in 2014 when the Regiment moved from wearing individual squadron county yeomanry cap badges to a unified single Regimental cap badge.

When Sophie, Countess of Wessex was granted arms, the sinister supporter assigned was a blue wyvern, described by the College of Arms as "an heraldic beast which has long been associated with Wessex".[36]

In the 1970s William Crampton, the founder of the British Flag Institute, designed a flag for the Wessex region which depicts a gold wyvern on a red field.[37]

Attributed coat of arms[edit]

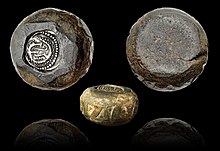

A coat of arms was attributed by medieval heralds to the Kings of Wessex. These arms appear in a manuscript of the 13th century, and are blazoned as Azure, a cross patonce (alternatively a cross fleury or cross moline) between four martlets Or.[38]

The attributed arms of Wessex are also known as the "Arms of Edward the Confessor", and the design is based on an emblem historically used by King Edward the Confessor on the reverse side of pennies minted by him. The heraldic design continued to represent both Wessex and Edward in classical heraldry[39] and is found on a number of church windows in derived shields such as the Arms of the Collegiate Church of St Peter at Westminster (Westminster Abbey, which was founded by the king).

Cultural and political identity in modern times[edit]

At its greatest extent Wessex encompassed the modern areas of Hampshire, Isle of Wight, Dorset and Wiltshire, as well as the western half of Berkshire and the eastern hilly flank of Somerset. This covers an area of about 11,500 km2 (4,400 sq mi).

The English author Thomas Hardy used a fictionalised Wessex as a setting for many of his novels, adopting his friend William Barnes' term Wessex for their home county of Dorset and its neighbouring counties in the south and west of England. Hardy's Wessex excluded Gloucestershire and Oxfordshire, but the city of Oxford, which he called "Christminster", was visited as part of Wessex in Jude the Obscure. He gave each of his Wessex counties a fictionalised name, such as with Berkshire, which is known in the novels as "North Wessex".

The film Shakespeare in Love included a character called "Lord Wessex" – a title which did not exist in Elizabethan times.

The ITV television series Broadchurch takes place in Wessex and its characters are seen attending South Wessex Secondary School.

See also[edit]

- Heptarchy

- Earl of Wessex

- List of monarchs of Wessex

- Wessex Constitutional Convention

- Wessex Regionalist Party

Bibliography[edit]

- Blair, Peter Hunter (17 July 2003). An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England (Third ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53777-3

- Yorke, Barbara (1995). Wessex in the Early Middle Ages. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-7185-1856-1.

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Peter Hunter Blair (17 July 2003). An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-521-53777-3.

- ^ Blair 2003, pp. 2–3

- ^ Blair 2003, p. 3

- ^ Yorke 1995, p. 11

- ^ Blair 2003, pp. 13–14

- ^ Blair 2003, pp. 14–16

- ^ Yorke, Barbara (1 November 2002). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. Routledge. pp. 130–131. ISBN 9781134707249.

- ^ Giles, John Allen (translator) (1914). The Anglo-Saxon chronicle. G. Bell and Sons, LTD. p. 9. Retrieved 27 July2015.

- ^ Yorke 2002, pp. 130–131

- ^ Yorke 2002, p. 130–131

- ^ Yorke, p. 131

- ^ Loyn, H. R. (1991). Anglo-Saxon England and the Norman Conquest (2 ed.). p. 34.

- ^ a b c d Giles, p. 9

- ^ Yorke 2002, p. 4

- ^ "Cerdicesford" is known with certainty to be Charford. (Major, p. 11)

- ^ Major, Albany F. Early Wars of Wessex (1912), pp. 11–20

- ^ Major, p. 19

- ^ Jackson, Kenneth (1953), Language and History in Early Britain. Edinburgh. pp. 554, 557, 613 and 680.

- ^ Parsons, D. (1997) British *Caraticos, Old English Cerdic, Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies, 33, pp, 1–8.

- ^ Koch, J.T., (2006) Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1-85109-440-7, pp. 394–395.

- ^ Koch, J.T., (2006) Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1-85109-440-7, pp. 392–393.

- ^ Yorke 1995, pp. 190–191

- ^ Myres, J.N.L. (1989) The English Settlements. Oxford University Press, pp. 146–147

- ^ Yorke, B. (1990), Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England, London: Seaby, ISBN 1-85264-027-8 pp. 138–139

- ^ Major, Albany F. Early Wars of Wessex, p.105

- ^ "Alfred the Great (849 AD – 899 AD)".

- ^ Hooper, Nicholas Hooper; Bennett, Matthew (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Warfare: the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 0-521-44049-1.

- ^ "Celtic Kingdoms of the British Isles: Dumnonii". The History Files. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ Albert S. Cook, Asser's life of King Alfred, 1906

- ^ Sawyer, Peter (2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings (3rd ed.). Oxford: OUP. p. 57. ISBN 0-19-285434-8.

- ^ The Burghal Hidage: Alfred's Towns, Alfred the Greatwebsite

- ^ J. S. P. Tatlock, The Dragons of Wessex and Wales in Speculum, Vol. 8, No. 2. (Apr., 1933), pp. 223–235.

- ^ "The Coat of Arms". Somerset County Council. Retrieved 14 January 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "Civic Heraldry of England and Wales – Cornwall and Wessex Area – Wiltshire County Council". Civicheraldry.co.uk. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ "Civic Heraldry of England and Wales – Cornwall and Wessex Area – Dorset County Council". Civicheraldry.co.uk. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ "The Arms of the Countess of Wessex". Royal Insight. Royal.gov.uk. 28 October 2010. Archived from the originalon 22 February 2008. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ The Flag Institute: Wessex. Retrieved 26 August 2015

- ^ College of Arms MS L.14, dating from the reign of Henry III

- ^ For example in Divi Britannici by Winston Churchill, published in 1675 and Britannia Saxona by G W Collen published in 1833

External links[edit]

- The Burghal Hidage

- Thomas Hardy's Wessex Research site by Dr Birgit Plietzsch

- The History Files: Kings of the West Saxons

- Wessex Law Academy

- Wessex Society

No comments:

Post a Comment