- I was trying to find what Article 50 actually says but I couldn't find it here. Maybe you can.This is a pretty interesting article about the European Union and it's structure either way.Begin quote from:

-

"EU" redirects here. For other uses, see EU (disambiguation).

The European Union (EU) is a politico- economic union of 28 member states that are located primarily in Europe.[12][13] It has an area of 4,324,782 km2 (1,669,808 sq mi), and an estimated population of over 508 million.

Flag Motto: "United in diversity"[1][2][3] Anthem: "Ode to Joy" (orchestral)[2]

Capital Brussels (de facto)[4]

50°51′N 4°21′ELargest cities London and Parisa Official languages Demonym European[5] Type Politico-economic union Member states Leaders • President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker • President of the European Council Donald Tusk • President of the European Parliament Martin Schulz Legislature Council of the EU

European ParliamentFormation[6] • Treaty of Rome 1 January 1958 • Treaty of Maastricht 1 November 1993 Area • Total 4,324,782 km2 (7th)

1,669,808 sq mi• Water (%) 3.08 Population • 2015 estimate 508,191,116[7] (3rd) • Density 115.8/km2

300.9/sq miGDP (PPP) 2015 estimate • Total $19.205 trillion[8] (2nd) • Per capita $37,852[8] (18thb) GDP (nominal) 2015 estimate • Total $16.220 trillion[8] (2nd) • Per capita $31,918[8] (15thb) Gini (2014) 30.9[9]

medium · 16thbHDI (2011)  0.876[10]

0.876[10]

very high · 13thbCurrency Time zone WET (UTC)c

CET (UTC+1)

EET (UTC+2)• Summer (DST) WEST (UTC+1)

CEST (UTC+2)

EEST (UTC+3)Internet TLD .eu[a] Website

europa.eu a. ^ London and Paris are the largest cities in the European Union by urban population.[11] b. ^ Ranked as a combined single entity. c. ^ Not including outermost regions.

The EU has developed an internal single market through a standardised system of laws that apply in all member states. EU policies aim to ensure the free movement of people, goods, services, and capital within the internal market,[14] enact legislation in justice and home affairs, and maintain common policies on trade,[15] agriculture,[16] fisheries, and regional development.[17] Within the Schengen Area, passport controls have been abolished.[18] A monetary union was established in 1999 and came into full force in 2002, and is composed of 19 EU member states which use the euro currency.

The EU operates through a hybrid system of supranational and intergovernmental decision-making.[19][20] The seven principal decision-making bodies—known as the institutions of the European Union—are the European Council, the Council of the European Union, the European Parliament, the European Commission, the Court of Justice of the European Union, the European Central Bank, and the European Court of Auditors.

The EU traces its origins from the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) and the European Economic Community (EEC), formed by the Inner Six countries in 1951 and 1958, respectively. The community and its successors have grown in size by the accession of new member states and in power by the addition of policy areas to its remit. The Maastricht Treaty established the European Union in 1993 and introduced European citizenship.[21] The latest major amendment to the constitutional basis of the EU, the Treaty of Lisbon, came into force in 2009. On 23 June 2016, the United Kingdom voted by referendum to leave the EU.[22]

Covering 7.3% of the world population,[23] the EU in 2014 generated a nominal gross domestic product (GDP) of 18.495 trillion US dollars, constituting approximately 24% of global nominal GDP and 17% when measured in terms of purchasing power parity.[24] Additionally, 26 out of 28 EU countries have a very high Human Development Index, according to the United Nations Development Program. In 2012, the EU was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.[25] Through the Common Foreign and Security Policy, the EU has developed a role in external relations and defence. The union maintains permanent diplomatic missions throughout the world and represents itself at the United Nations, the World Trade Organization, the G8, and the G-20. Because of its global influence, the European Union has been described as a current or as a potential superpower.[26]

Contents

History

Main articles: History of the European Union and History of EuropePreliminary (1945–57)

After World War II, European integration was seen as an antidote to the extreme nationalism which had devastated the continent.[27] The 1948 Hague Congress was a pivotal moment in European federal history, as it led to the creation of the European Movement International and of the College of Europe, where Europe's future leaders would live and study together.[28] 1952 saw the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community, which was declared to be "a first step in the federation of Europe."[29] The supporters of the Community included Alcide De Gasperi, Jean Monnet, Robert Schuman, and Paul-Henri Spaak.[30]

Treaty of Rome (1957–92)

In 1957, Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and West Germany signed the Treaty of Rome, which created the European Economic Community (EEC) and established a customs union. They also signed another pact creating the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom) for co-operation in developing nuclear energy. Both treaties came into force in 1958.[30]The continental territories of the member states of the European Union (European Communities pre-1993), coloured in order of accession.

The EEC and Euratom were created separately from ECSC, although they shared the same courts and the Common Assembly. The EEC was headed by Walter Hallstein (Hallstein Commission) and Euratom was headed by Louis Armand (Armand Commission) and then Étienne Hirsch. Euratom was to integrate sectors in nuclear energy while the EEC would develop a customs union among members.[31][32]

Through the 1960s, tensions began to show, with France seeking to limit supranational power. Nevertheless, in 1965 an agreement was reached and on 1 July 1967 the Merger Treaty created a single set of institutions for the three communities, which were collectively referred to as the European Communities.[33][34] Jean Rey presided over the first merged Commission (Rey Commission).[35]

In 1973, the Communities enlarged to include Denmark (including Greenland, which later left the Community in 1985, following a dispute over fishing rights), Ireland, and the United Kingdom.[36] Norway had negotiated to join at the same time, but Norwegian voters rejected membership in a referendum. In 1979, the first direct elections to the European Parliament were held.[37]

Greece joined in 1981, Portugal and Spain following in 1986.[38] In 1985, the Schengen Agreement paved the way for the creation of open borders without passport controls between most member states and some non-member states.[39] In 1986, the European flag began to be used by the Community[40] and the Single European Act was signed.

In 1990, after the fall of the Eastern Bloc, the former East Germany became part of the Community as part of a reunified Germany.[41] With further enlargement planned to include the former communist states, as well as Cyprus and Malta, the Copenhagen criteria for candidate members to join the EU were agreed upon in June 1993.

Maastricht Treaty (1992–present)

The European Union was formally established when the Maastricht Treaty—whose main architects were Helmut Kohl and François Mitterrand—came into force on 1 November 1993.[21] The treaty also gave the name European Community to the EEC, even if it was referred as such before the treaty. In 1995, Austria, Finland, and Sweden joined the EU. In 2002, euro banknotes and coins replaced national currencies in 12 of the member states. Since then, the eurozone has increased to encompass 19 countries. In 2004, the EU saw its biggest enlargement to date when Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia joined the Union.[42] In 2007, Romania and Bulgaria became EU members. The same year, Slovenia adopted the euro,[42] followed in 2008 by Cyprus and Malta, by Slovakia in 2009, by Estonia in 2011, by Latvia in 2014 and by Lithuania in 2015.The euro was introduced in 2002, replacing 12 national currencies. Seven countries have since joined.

On 1 December 2009, the Lisbon Treaty entered into force and reformed many aspects of the EU. In particular, it changed the legal structure of the European Union, merging the EU three pillars system into a single legal entity provisioned with a legal personality, created a permanent President of the European Council, the first of which was Herman Van Rompuy, and strengthened the position of the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy.[43][44] In 2012, the EU received the Nobel Peace Prize for having "contributed to the advancement of peace and reconciliation, democracy, and human rights in Europe."[45][46] In 2013, Croatia became the 28th EU member.[47][48][49]2009, the Lisbon Treaty entered into force.

From the beginning of 2010s, the European Union is going through a series of tests, including debt crisis in some Eurozone countries, increasing migration from the Middle East countries, Russian military intervention in Ukraine and the United Kingdom withdrawal from the EU.

Structural evolution

Main article: Treaties of the European UnionThe following timeline illustrates the integration that has led to the formation of the present union, in terms of structural development driven by international treaties:

Signed

In force

Document1948

1948

Brussels Treaty1951

1952

Paris Treaty1954

1955

Modified Brussels Treaty1957

1958

Rome treaties1965

1967

Merger Treaty1975

N/A

European Council conclusion1985

1995

Schengen Treaty1986

1987

Single European Act1992

1993

Maastricht Treaty1997

1999

Amsterdam Treaty2001

2003

Nice Treaty2007

2009

Lisbon TreatyThree pillars of the European Union: European Communities: European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM) European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) Treaty expired in 2002 European Union (EU) European Economic Community (EEC) Schengen Rules European Community (EC) TREVI Justice and Home Affairs (JHA) Police and Judicial Co-operation in Criminal Matters (PJCC) European Political Cooperation (EPC) Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) Unconsolidated bodies Western European Union (WEU) Treaty terminated in 2011 UK referendum

On 20 February 2016, British Prime Minister David Cameron announced that a referendum on the UK's membership of the European Union would be held on 23 June 2016, following years of campaigning by eurosceptics. Debates and campaigns by parties supporting both "Remain" and "Leave" focused on concerns regarding trade and the single market, security, migration and sovereignty. The result of the referendum was in favour of the country leaving the EU with 51.9% of voters wanting to leave.[50] The UK remains a member for the time being, but pending invocation of Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, will begin negotiations on a withdrawal agreement that will last no more than two years (unless the Council and the UK agree to extend the negotiation period) which will ultimately lead to an exit from the Union.[51] The implications of the referendum vote remain unknown, with politicians and commentators suggesting various outcomes.[52][53]This article or section might be slanted towards recent events. (June 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

Geography

Main article: Geography of the European UnionThe EU's member states cover an area of 4,423,147 square kilometres (1,707,787 sq mi).[b] The EU's highest peak is Mont Blanc in the Graian Alps, 4,810.45 metres (15,782 ft) above sea level.[54] The lowest points in the EU are Lammefjorden, Denmark and Zuidplaspolder, Netherlands, at 7 m (23 ft) below sea level.[55] The landscape, climate, and economy of the EU are influenced by its coastline, which is 65,993 kilometres (41,006 mi) long.The 65,993 km (41,006 mi) coastline dominates the European climate (Cyprus).Mont Blanc in the Alps is the highest peak in the EU.

Including the overseas territories of France which are located outside the continent of Europe, but which are members of the union, the EU experiences most types of climate from Arctic (North-East Europe) to tropical (French Guyana), rendering meteorological averages for the EU as a whole meaningless. The majority of the population lives in areas with a temperate maritime climate (North-Western Europe and Central Europe), a Mediterranean climate (Southern Europe), or a warm summer continental or hemiboreal climate (Northern Balkans and Central Europe).[56]

The EU's population is highly urbanised, with some 75% of inhabitants (and growing, projected to be 90% in seven member states by 2020) living in urban areas. Cities are largely spread out across the EU, although with a large grouping in and around the Benelux. An increasing percentage of this is due to low density urban sprawl which is extending into natural areas. In some cases, this urban growth has been due to the influx of EU funds into a region.[57]

Member states

Main article: Member state of the European UnionPart of a series of articles on the United Kingdom

in the

European Union Through successive enlargements, the European Union has grown from the six founding states—Belgium, France, West Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands—to the current 28. Countries accede to the union by becoming party to the founding treaties, thereby subjecting themselves to the privileges and obligations of EU membership. This entails a partial delegation of sovereignty to the institutions in return for representation within those institutions, a practice often referred to as "pooling of sovereignty".[58][59]Map of the European Union in the world with overseas countries and territories and outermost regions.

Through successive enlargements, the European Union has grown from the six founding states—Belgium, France, West Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands—to the current 28. Countries accede to the union by becoming party to the founding treaties, thereby subjecting themselves to the privileges and obligations of EU membership. This entails a partial delegation of sovereignty to the institutions in return for representation within those institutions, a practice often referred to as "pooling of sovereignty".[58][59]Map of the European Union in the world with overseas countries and territories and outermost regions.

To become a member, a country must meet the Copenhagen criteria, defined at the 1993 meeting of the European Council in Copenhagen. These require a stable democracy that respects human rights and the rule of law; a functioning market economy; and the acceptance of the obligations of membership, including EU law. Evaluation of a country's fulfilment of the criteria is the responsibility of the European Council.[60] No member state has yet left the Union, although Greenland (an autonomous province of Denmark) withdrew in 1985.[61] The Lisbon Treaty now contains a clause under Article 50, providing for a member to leave the EU.[62] On 23 June 2016, the United Kingdom voted by referendum to leave the EU. However, it remains a member until it officially exits, and has not yet begun formal withdrawal procedures.[22]

There are six countries that are recognized as candidates for membership: Albania, Iceland, Macedonia,[c] Montenegro, Serbia, and Turkey,[63] though Iceland suspended negotiations in 2013.[64] Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo are officially recognised as potential candidates,[63] with Bosnia and Herzegovina having submitted a membership application.

The four countries forming the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) are not EU members, but have partly committed to the EU's economy and regulations: Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway, which are a part of the single market through the European Economic Area, and Switzerland, which has similar ties through bilateral treaties.[65][66] The relationships of the European microstates, Andorra, Monaco, San Marino, and the Vatican include the use of the euro and other areas of co-operation.[67] The following 28 sovereign states (of which the map only shows territories situated in and around Europe) constitute the European Union:[68]

Name Capital Accession Population[7] Area (km2)  Austria

AustriaVienna 1 January 1995 8,584,926 83,855  Belgium

BelgiumBrussels Founder 11,258,434 30,528  Bulgaria

BulgariaSofia 1 January 2007 7,202,198 110,994  Croatia

CroatiaZagreb 1 July 2013 4,225,316 56,594  Cyprus

CyprusNicosia 1 May 2004 1,141,166 9,251  Czech Republic

Czech RepublicPrague 1 May 2004 10,538,275 78,866  Denmark

DenmarkCopenhagen 1 January 1973 5,659,715 43,075  Estonia

EstoniaTallinn 1 May 2004 1,313,271 45,227  Finland

FinlandHelsinki 1 January 1995 5,471,753 338,424  France

FranceParis Founder 66,352,469 640,679  Germany

GermanyBerlin Founder[d] 81,174,000 357,021  Greece

GreeceAthens 1 January 1981 10,812,467 131,990  Hungary

HungaryBudapest 1 May 2004 9,849,000 93,030  Ireland

IrelandDublin 1 January 1973 4,625,885 70,273  Italy

ItalyRome Founder 60,795,612 301,338  Latvia

LatviaRiga 1 May 2004 1,986,096 64,589  Lithuania

LithuaniaVilnius 1 May 2004 2,921,262 65,200  Luxembourg

LuxembourgLuxembourg City Founder 562,958 2,586  Malta

MaltaValletta 1 May 2004 429,344 316  Netherlands

NetherlandsAmsterdam Founder 16,900,726 41,543  Poland

PolandWarsaw 1 May 2004 38,005,614 312,685  Portugal

PortugalLisbon 1 January 1986 10,374,822 92,390  Romania

RomaniaBucharest 1 January 2007 19,861,408 238,391  Slovakia

SlovakiaBratislava 1 May 2004 5,421,349 49,035  Slovenia

SloveniaLjubljana 1 May 2004 2,062,874 20,273  Spain

SpainMadrid 1 January 1986 46,439,864 504,030  Sweden

SwedenStockholm 1 January 1995 9,747,355 449,964  United Kingdom

United KingdomLondon 1 January 1973 64,767,115 243,610 Environment

Further information: European Commissioner for the Environment and European Climate Change ProgrammeIn 1957, when the EEC was founded, it had no environmental policy.[69] Over the past 50 years, an increasingly dense network of legislation has been created, extending to all areas of environmental protection, including air pollution, water quality, waste management, nature conservation, and the control of chemicals, industrial hazards and biotechnology.[70] According to the Institute for European Environmental Policy, environmental law comprises over 500 Directives, Regulations and Decisions, making environmental policy a core area of European politics.[71]

European policy-makers originally increased the EU's capacity to act on environmental issues by defining it as a trade problem.[72] Trade barriers and competitive distortions in the Common Market could emerge due to the different environmental standards in each member state.[73] In subsequent years, the environment became a formal policy area, with its own policy actors, principles and procedures. The legal basis for EU environmental policy was established with the introduction of the Single European Act in 1987.[71]

Initially, EU environmental policy focused on Europe. More recently, the EU has demonstrated leadership in global environmental governance, e.g. the role of the EU in securing the ratification and coming into force of the Kyoto Protocol despite opposition from the United States. This international dimension is reflected in the EU's Sixth Environmental Action Programme,[74] which recognises that its objectives can only be achieved if key international agreements are actively supported and properly implemented both at EU level and worldwide. The Lisbon Treaty further strengthened the leadership ambitions.[75] EU law has played a significant role in improving habitat and species protection in Europe, as well as contributing to improvements in air and water quality and waste management.[71]A black stork, a protected species under Regulation (EC) No. 338/97

Mitigating climate change is one of the top priorities of EU environmental policy. In 2007, member states agreed that, in future, 20% of the energy used across the EU must be renewable, and carbon dioxide emissions have to be lower in 2020 by at least 20% compared to 1990 levels.[76] The EU has adopted an emissions trading system to incorporate carbon emissions into the economy.[77] The European Green Capital is an annual award given to cities that focuses on the environment, energy efficiency and quality of life in urban areas to create smart city.

Politics

Main article: Politics of the European UnionThe European Union operates according to the principles of conferral (which says that it should act only within the limits of the competences conferred on it by the treaties) and of subsidiarity (which says that it should act only where an objective cannot be sufficiently achieved by the member states acting alone). Laws made by the EU institutions are passed in a variety of forms. Generally speaking, they can be classified into two groups: those which come into force without the necessity for national implementation measures (regulations) and those which specifically require national implementation measures (directives).[78]

Constitutional nature

Further information: Treaties of the European UnionThe classification of the EU in terms of international or constitutional law has been much debated. It began life as an international organisation and gradually developed into a confederation of states. However, since the mid-1960s it has also added several of the key attributes of a federation, such as the direct effect of the law of the general level of government upon the individual[79] and majority voting in the decision-making process of the general level of government,[80] without becoming a federation per se. Scholars thus today see it as an intermediate form lying between a confederation and a federation, being an instance of neither political structure.[81] For this reason, the organisation is termed sui generis (incomparable, one of a kind),[82] although some argue that this designation is no longer valid.[83][84]Political system of the European Union

The organisation has traditionally used the terms "Community" and later "Union" to describe itself. The difficulties of classification involve the difference between national law (where the subjects of the law include natural persons and corporations) and international law (where the subjects include sovereign states and international organizations). They can also be seen in the light of differing European and American constitutional traditions.[83] Especially in terms of the European tradition, the term federation is equated with a sovereign federal state in international law; so the EU cannot be called a federation — at least, not without qualification. It is, however, described as being based on a federal model or federal in nature; and so it may be appropriate to consider it a federal union of states, a conceptual structure lying between the confederation of states and the federal state.[85] The German Constitutional Court refers to the EU as a Staatenverbund, an intermediate structure between the Staatenbund (confederation of states) and the Bundesstaat (federal state), consistent with this concept.[86] This may be a long-lived political form. Professor Andrew Moravcsik claims that the EU is unlikely to develop further into a federal state, but instead has reached maturity as a constitutional system.[87]

Governance

Main articles: Institutions of the European Union and Legislature of the European UnionThe European Union has seven institutions: the European Council, the Council of the European Union, the European Parliament, the European Commission, the Court of Justice of the European Union, the European Central Bank and the European Court of Auditors. Competence in scrutinising and amending legislation is shared between the Council of the European Union and the European Parliament, while executive tasks are performed by the European Commission and in a limited capacity by the European Council (not to be confused with the aforementioned Council of the European Union). The monetary policy of the eurozone is determined by the European Central Bank. The interpretation and the application of EU law and the treaties are ensured by the Court of Justice of the European Union. The EU budget is scrutinised by the European Court of Auditors. There are also a number of ancillary bodies which advise the EU or operate in a specific area.

Institutions of the European Union [88]European Council

- Provides impetus and direction -

Council of the European Union

- Legislature -

European Parliament

- Legislature -

European Commission

- Executive -

- summit of the Heads of state or government, the President of the European Council and the President of the European Commission.

- gives the necessary political impetus for the development of the Union and sets its general objectives and priorities

- will not legislate

- based in Brussels

- acts together with the Parliament as a legislature

- shares with the Parliament the budgetary power

- ensures coordination of the broad economic and social policy and sets out guidelines for the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP)

- concludes international agreements

- based in Brussels

- acts together with the Council as a legislature

- shares with the Council the budgetary power and decides in the last instance on the budget

- exerts the democratic control over the institutions including the European Commission and approves the Commission members

- based in and plenary sessions in Strasbourg, primarily meets in Brussels

- is the executive

- submits proposals for new legislation to the Parliament and Council

- implements policies

- administers the budget

- ensures compliance with European law ("guardian of the treaties")

- negotiates international agreements

- based in Brussels

Court of Justice of the European Union

- Judiciary -

European Central Bank

- Central bank -

European Court of Auditors

- Financial auditor -

- ensures the uniform application and interpretation of European law

- has the power to decide legal disputes between member states, the institutions, businesses and individuals

- based in Luxembourg

- forms together with the national central banks the European System of Central Banks and thereby determines the monetary policy of the eurozone

- ensures price stability in the eurozone by controlling the money supply

- based in Frankfurt

- checks the proper implementation of the budget

- based in Luxembourg

European Council

The European Council gives political direction to the EU. It convenes at least four times a year and comprises the President of the European Council (currently Donald Tusk), the President of the European Commission and one representative per member state (either its head of state or head of government). The High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (currently Federica Mogherini) also takes part in its meetings. It has been described by some as the Union's "supreme political authority".[89] It is actively involved in the negotiation of treaty changes and defines the EU's policy agenda and strategies.

The European Council uses its leadership role to sort out disputes between member states and the institutions, and to resolve political crises and disagreements over controversial issues and policies. It acts externally as a "collective head of state" and ratifies important documents (for example, international agreements and treaties).[90]

Tasks for the President of the European Council are ensuring the external representation of the EU,[91] driving consensus and resolving divergences among member states, both during meetings of the European Council and over the periods between them.

The European Council should not be mistaken for the Council of Europe, an international organisation independent of the EU based in Strasbourg.

Council of the European Union

The Council of the European Union (also called the "Council"[92] and the "Council of Ministers", its former title)[93] forms one half of the EU's legislature. It consists of a government minister from each member state and meets in different compositions depending on the policy area being addressed. Notwithstanding its different configurations, it is considered to be one single body.[94] In addition to its legislative functions, the Council also exercises executive functions in relations to the Common Foreign and Security Policy.

European Parliament

The European Parliament forms the other half of the EU's legislature. The 751 Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) are directly elected by EU citizens every five years on the basis of proportional representation. Although MEPs are elected on a national basis, they sit according to political groups rather than their nationality. Each country has a set number of seats and is divided into sub-national constituencies where this does not affect the proportional nature of the voting system.[95]The hemicycle of the European Parliament in Strasbourg

The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union pass legislation jointly in nearly all areas under the ordinary legislative procedure. This also applies to the EU budget. The European Commission is accountable to Parliament, requiring its approval to take office, having to report back to it and subject to motions of censure from it. The President of the European Parliament (currently Martin Schulz) carries out the role of speaker in Parliament and represents it externally. The President and Vice-Presidents are elected by MEPs every two and a half years.[96]

European Commission

The European Commission acts as the EU's executive arm and is responsible for initiating legislation and the day-to-day running of the EU. The Commission is also seen as the motor of European integration. It operates as a cabinet government, with 28 Commissioners for different areas of policy, one from each member state, though Commissioners are bound to represent the interests of the EU as a whole rather than their home state.

One of the 28 is the President of the European Commission (currently Jean-Claude Juncker) appointed by the European Council. After the President, the most prominent Commissioner is the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, who is ex-officio a Vice-President of the Commission and is also chosen by the European Council.[97] The other 26 Commissioners are subsequently appointed by the Council of the European Union in agreement with the nominated President. The 28 Commissioners as a single body are subject to a vote of approval by the European Parliament.

Budget

Main article: Budget of the European UnionThe EU had an agreed budget of €120.7 billion for the year 2007 and €864.3 billion for the period 2007–2013,[99] representing 1.10% and 1.05% of the EU-27's GNI forecast for the respective periods. By comparison, the United Kingdom's expenditure for 2004 was estimated to be €759 billion, and France was estimated to have spent €801 billion. In 1960, the budget of the then European Economic Community was 0.03% of GDP.[100]The 2011 EU budget (€141.9 bn)[98]

Cohesion and competitiveness for growth and employment (45%)Direct aids and market related expenditures (31%)Rural development (11%)EU as a global partner (6%)Administration (6%)Citizenship, freedom, security and justice (1%)

In the 2010 budget of €141.5 billion, the largest single expenditure item is "cohesion & competitiveness" with around 45% of the total budget.[101] Next comes "agriculture" with approximately 31% of the total.[101] "Rural development, environment and fisheries" takes up around 11%.[101] "Administration" accounts for around 6%.[101] The "EU as a global partner" and "citizenship, freedom, security and justice" bring up the rear with approximately 6% and 1% respectively.[101]

The Court of Auditors is legally obliged to provide the Parliament and the Council with "a statement of assurance as to the reliability of the accounts and the legality and regularity of the underlying transactions".[102] The Court also gives opinions and proposals on financial legislation and anti-fraud actions.[103] The Parliament uses this to decide whether to approve the Commission's handling of the budget.

The European Court of Auditors has signed off the European Union accounts every year since 2007 and, while making it clear that the European Commission has more work to do, has highlighted that most of the errors take place at national level.[104][105] In their report on 2009 the auditors found that five areas of Union expenditure, agriculture and the cohesion fund, were materially affected by error.[106] The European Commission estimated in 2009 that the financial impact of irregularities was €1,863 million.[107]

Competences

EU member states retain all powers not explicitly handed to the European Union. In some areas the EU enjoys exclusive competence. These are areas in which member states have renounced any capacity to enact legislation. In other areas the EU and its member states share the competence to legislate. While both can legislate, member states can only legislate to the extent to which the EU has not. In other policy areas the EU can only co-ordinate, support and supplement member state action but cannot enact legislation with the aim of harmonising national laws.[108]

That a particular policy area falls into a certain category of competence is not necessarily indicative of what legislative procedure is used for enacting legislation within that policy area. Different legislative procedures are used within the same category of competence, and even with the same policy area.

The distribution of competences in various policy areas between Member States and the Union is divided in the following three categories:

As outlined in Title I of Part I of the consolidated Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union Exclusive competence Shared competence Supporting competence "The Union has exclusive competence to make directives and conclude international agreements when provided for in a Union legislative act." - the customs union

- the establishing of the competition rules necessary for the functioning of the internal market

- monetary policy for the Member States whose currency is the euro

- the conservation of marine biological resources under the common fisheries policy

- common commercial policy

- conclusion of certain international agreements

"Member States cannot exercise competence in areas where the Union has done so." - the internal market

- social policy, for the aspects defined in this Treaty

- economic, social and territorial cohesion

- agriculture and fisheries, excluding the conservation of marine biological resources

- environment

- consumer protection

- transport

- trans-European networks

- energy

- the area of freedom, security and justice

- common safety concerns in public health matters, for the aspects defined in this Treaty

"Union exercise of competence shall not result in Member States being prevented from exercising theirs in" … - research, technological development and (outer) space

- development cooperation, humanitarian aid

"The Union coordinates Member States policies or implements supplemental to theirs common policies, not covered elsewhere" - coordination of economic, employment and social policies

- common foreign, security and defence policies

"The Union can carry out actions to support, coordinate or supplement Member States' actions in" … Legal system

Further information: European Union law, Treaties of the European Union, and Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European UnionThe EU is based on a series of treaties. These first established the European Community and the EU, and then made amendments to those founding treaties.[109] These are power-giving treaties which set broad policy goals and establish institutions with the necessary legal powers to implement those goals. These legal powers include the ability to enact legislation[e] which can directly affect all member states and their inhabitants.[f] The EU has legal personality, with the right to sign agreements and international treaties.[110]The Court of Justice, seated in Luxembourg.

Under the principle of supremacy, national courts are required to enforce the treaties that their member states have ratified, and thus the laws enacted under them, even if doing so requires them to ignore conflicting national law, and (within limits) even constitutional provisions.[g]

Courts of Justice

The judicial branch of the EU—formally called the Court of Justice of the European Union—consists of three courts: the Court of Justice, the General Court, and the European Union Civil Service Tribunal. Together they interpret and apply the treaties and the law of the EU.[111]

The Court of Justice primarily deals with cases taken by member states, the institutions, and cases referred to it by the courts of member states.[112] The General Court mainly deals with cases taken by individuals and companies directly before the EU's courts,[113] and the European Union Civil Service Tribunal adjudicates in disputes between the European Union and its civil service.[114] Decisions from the General Court can be appealed to the Court of Justice but only on a point of law.[115]

Fundamental rights

The treaties declare that the EU itself is "founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities ... in a society in which pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between women and men prevail."[116]The ceremony of the 1990 Sakharov Prize awarded to Aung San Suu Kyi by Martin Schulz, inside the Parliament's Strasbourg hemicycle, in 2013.

In 2009 the Lisbon Treaty gave legal effect to the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. The charter is a codified catalogue of fundamental rights against which the EU's legal acts can be judged. It consolidates many rights which were previously recognised by the Court of Justice and derived from the "constitutional traditions common to the member states."[117] The Court of Justice has long recognised fundamental rights and has, on occasion, invalidated EU legislation based on its failure to adhere to those fundamental rights.[118]

Although signing the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) is a condition for EU membership,[h] previously, the EU itself could not accede to the Convention as it is neither a state[i] nor had the competence to accede.[j] The Lisbon Treaty and Protocol 14 to the ECHR have changed this: the former binds the EU to accede to the Convention while the latter formally permits it.

Although, the EU is independent from Council of Europe, they share purpose and ideas especially on rule of law, human rights and democracy. Further European Convention on Human Rights and European Social Charter, the source of law of Charter of Fundamental Rights are created by Council of Europe. The EU also promoted human rights issues in the wider world. The EU opposes the death penalty and has proposed its worldwide abolition. Abolition of the death penalty is a condition for EU membership.[119]

Acts

The main legal acts of the EU come in three forms: regulations, directives, and decisions. Regulations become law in all member states the moment they come into force, without the requirement for any implementing measures,[k] and automatically override conflicting domestic provisions.[e] Directives require member states to achieve a certain result while leaving them discretion as to how to achieve the result. The details of how they are to be implemented are left to member states.[l] When the time limit for implementing directives passes, they may, under certain conditions, have direct effect in national law against member states.

Decisions offer an alternative to the two above modes of legislation. They are legal acts which only apply to specified individuals, companies or a particular member state. They are most often used in competition law, or on rulings on State Aid, but are also frequently used for procedural or administrative matters within the institutions. Regulations, directives, and decisions are of equal legal value and apply without any formal hierarchy.[120]

Area of freedom, security and justice

Further information: Area of freedom, security and justiceSince the creation of the EU in 1993, it has developed its competencies in the area of freedom, security and justice, initially at an intergovernmental level and later by supranationalism. To this end, agencies have been established that co-ordinate associated actions: Europol for co-operation of police forces,[121] Eurojust for co-operation between prosecutors,[122] and Frontex for co-operation between border control authorities.[123] The EU also operates the Schengen Information System[18] which provides a common database for police and immigration authorities. This co-operation had to particularly be developed with the advent of open borders through the Schengen Agreement and the associated cross border crime.The borders inside the Schengen Area between Germany and Austria

Furthermore, the Union has legislated in areas such as extradition,[124] family law,[125] asylum law,[126] and criminal justice.[127] Prohibitions against sexual and nationality discrimination have a long standing in the treaties.[m] In more recent years, these have been supplemented by powers to legislate against discrimination based on race, religion, disability, age, and sexual orientation.[n] By virtue of these powers, the EU has enacted legislation on sexual discrimination in the work-place, age discrimination, and racial discrimination.[o]

Foreign relations

Main articles: Foreign relations of the European Union, Common Foreign and Security Policy and European External Action ServiceForeign policy co-operation between member states dates from the establishment of the Community in 1957, when member states negotiated as a bloc in international trade negotiations under the Common Commercial policy.[128] Steps for a more wide ranging co-ordination in foreign relations began in 1970 with the establishment of European Political Cooperation which created an informal consultation process between member states with the aim of forming common foreign policies. It was not, however, until 1987 when European Political Cooperation was introduced on a formal basis by the Single European Act. EPC was renamed as the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) by the Maastricht Treaty.[129]

The aims of the CFSP are to promote both the EU's own interests and those of the international community as a whole, including the furtherance of international co-operation, respect for human rights, democracy, and the rule of law.[130] The CFSP requires unanimity among the member states on the appropriate policy to follow on any particular issue. The unanimity and difficult issues treated under the CFSP sometimes lead to disagreements, such as those which occurred over the war in Iraq.[131]

The coordinator and representative of the CFSP within the EU is the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy who speaks on behalf of the EU in foreign policy and defence matters, and has the task of articulating the positions expressed by the member states on these fields of policy into a common alignment. The High Representative heads up the European External Action Service (EEAS), a unique EU department[132] that has been officially implemented and operational since 1 December 2010 on the occasion of the first anniversary of the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon.[133] The EEAS will serve as a foreign ministry and diplomatic corps for the European Union.[134]

Besides the emerging international policy of the European Union, the international influence of the EU is also felt through enlargement. The perceived benefits of becoming a member of the EU act as an incentive for both political and economic reform in states wishing to fulfil the EU's accession criteria, and are considered an important factor contributing to the reform of European formerly Communist countries.[135]:762 This influence on the internal affairs of other countries is generally referred to as "soft power", as opposed to military "hard power".[136]

Military

Main article: Military of the European UnionThe predecessors of the European Union were not devised as a military alliance because NATO was largely seen as appropriate and sufficient for defence purposes.[137] 22 EU members are members of NATO[138] while the remaining member states follow policies of neutrality.[139] The Western European Union, a military alliance with a mutual defence clause, was disbanded in 2010 as its role had been transferred to the EU.[140]

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), the United Kingdom spent $61 billion on defence in 2014, placing it fifth in the world, while France spent $53 billion, the sixth largest.[141] Together, the UK and France account for approximately 40 per cent of EU's defence budget and 50 per cent of its military capacity.[142] Both are officially recognised nuclear weapon states holding permanent seats on the United Nations Security Council.An A400M military transport aircraft built by Airbus Group SE (Societas Europaea; Latin: European company)

Following the Kosovo War in 1999, the European Council agreed that "the Union must have the capacity for autonomous action, backed by credible military forces, the means to decide to use them, and the readiness to do so, in order to respond to international crises without prejudice to actions by NATO". To that end, a number of efforts were made to increase the EU's military capability, notably the Helsinki Headline Goal process. After much discussion, the most concrete result was the EU Battlegroups initiative, each of which is planned to be able to deploy quickly about 1500 personnel.[143]

EU forces have been deployed on peacekeeping missions from middle and northern Africa to the western Balkans and western Asia.[144] EU military operations are supported by a number of bodies, including the European Defence Agency, European Union Satellite Centre and the European Union Military Staff.[145] Frontex is an agency of the EU established to manage the cooperation between national border guards securing its external borders. It aims to detect and stop illegal immigration, human trafficking and terrorist infiltration. In December 2015 the European Commission presented its proposal for a new European Border and Coast Guard Agency having a stronger role and mandate along with national authorities for border management. In an EU consisting of 28 members, substantial security and defence co-operation is increasingly relying on collaboration among all member states.[146]

Humanitarian aid

Further information: ECHO (European Commission)The European Commission's Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection department, or "ECHO", provides humanitarian aid from the EU to developing countries. In 2012, its budget amounted to €874 million, 51% of the budget went to Africa and 20% to Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean and Pacific, and 20% to the Middle East and Mediterranean.[149]

Humanitarian aid is financed directly by the budget (70%) as part of the financial instruments for external action and also by the European Development Fund (30%).[150] The EU's external action financing is divided into 'geographic' instruments and 'thematic' instruments.[150] The 'geographic' instruments provide aid through the Development Cooperation Instrument (DCI, €16.9 billion, 2007–2013), which must spend 95% of its budget on overseas development assistance (ODA), and from the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI), which contains some relevant programmes.[150] The European Development Fund (EDF, €22.7 bn, 2008–2013) is made up of voluntary contributions by member states, but there is pressure to merge the EDF into the budget-financed instruments to encourage increased contributions to match the 0.7% target and allow the European Parliament greater oversight.[150]

However, five countries have reached the 0.7% target: Sweden, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Denmark and the United Kingdom.[151][152] In 2011, EU aid was 0.42% of the EU's GNI making it the world's most generous aid donor.[153] The previous Commissioner for Aid, Louis Michel, has called for aid to be delivered more rapidly, to greater effect, and on humanitarian principles.[154]

Economy

Main articles: Economy of the European Union and Regional policy of the European UnionThe European Union has established a single market across the territory of all its members representing 508 million citizens. In 2014, the EU had a combined GDP of 18.640 trillion international dollars, a 20% share of global gross domestic product by purchasing power parity (PPP).[156] As a political entity the European Union is represented in the World Trade Organization (WTO). EU member states own the estimated largest net wealth in the world, equal to 30% of the $223 trillion global wealth.2015 GDP (nominal) in EU

19 member states have joined a monetary union known as the eurozone, which uses the Euro as a single currency. The currency union represents 338 million EU citizens.[157] The euro is the second largest reserve currency as well as the second most traded currency in the world after the United States dollar.[158][159][160]GDP (in PPS) per inhabitant by NUTS 2 regions in 2013.

Of the top 500 largest corporations in the world measured by revenue in 2010, 161 have their headquarters in the EU.[161] In 2016, unemployment in the EU stood at 8.9%[162] while inflation was at 2.2%, and the current account balance at −0.9% of GDP.

There is a significant variance for GDP (PPP) per capita within individual EU states. The difference between the richest and poorest regions (276 NUTS-2 regions of the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics) ranged, in 2014, from 30% of the EU28 average to 539%, or from €8,200 to €148,000 (about US$9,000 to US$162,000).[163]

Structural Funds and Cohesion Funds are supporting the development of underdeveloped regions of the EU. Such regions are primarily located in the states of central and southern Europe.[164][165] Several funds provide emergency aid, support for candidate members to transform their country to conform to the EU's standard (Phare, ISPA, and SAPARD), and support to the Commonwealth of Independent States (TACIS). TACIS has now become part of the worldwide EuropeAid programme. EU research and technological framework programmes sponsor research conducted by consortia from all EU members to work towards a single European Research Area.[166]

Internal market

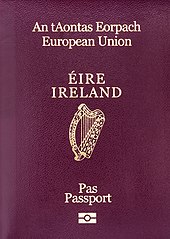

Main article: Internal marketTwo of the original core objectives of the European Economic Community were the development of a common market, subsequently becoming a single market, and a customs union between its member states. The single market involves the free circulation of goods, capital, people, and services within the EU,[157] and the customs union involves the application of a common external tariff on all goods entering the market. Once goods have been admitted into the market they cannot be subjected to customs duties, discriminatory taxes or import quotas, as they travel internally. The non-EU member states of Iceland, Norway, Liechtenstein and Switzerland participate in the single market but not in the customs union.[65] Half the trade in the EU is covered by legislation harmonised by the EU.[167]A standardised passport design, displaying the name of the member state, the national arms and the words "European Union" given in their official language(s). (Irish model)

Free movement of capital is intended to permit movement of investments such as property purchases and buying of shares between countries.[168] Until the drive towards economic and monetary union the development of the capital provisions had been slow. Post-Maastricht there has been a rapidly developing corpus of ECJ judgements regarding this initially neglected freedom. The free movement of capital is unique insofar as it is granted equally to non-member states.

The free movement of persons means that EU citizens can move freely between member states to live, work, study or retire in another country. This required the lowering of administrative formalities and recognition of professional qualifications of other states.[169]

The free movement of services and of establishment allows self-employed persons to move between member states to provide services on a temporary or permanent basis. While services account for 60–70% of GDP, legislation in the area is not as developed as in other areas. This lacuna has been addressed by the recently passed Directive on services in the internal market which aims to liberalise the cross border provision of services.[170] According to the Treaty the provision of services is a residual freedom that only applies if no other freedom is being exercised.

Monetary union

Main articles: Eurozone and Economic and Monetary Union of the European UnionThe creation of a European single currency became an official objective of the European Economic Community in 1969. In 1992, having negotiated the structure and procedures of a currency union, the member states signed the Maastricht Treaty and were legally bound to fulfil the agreed-on rules including the convergence criteria if they wanted to join the monetary union. The states wanting to participate had first to join the European Exchange Rate Mechanism.The seat of the European Central Bank in Frankfurt. 19 of the 28 EU member states have adopted the euro as their legal tender.

In 1999 the currency union started, first as an accounting currency with eleven member states joining. In 2002, the currency was fully put into place, when euro notes and coins were issued and national currencies began to phase out in the eurozone, which by then consisted of 12 member states. The eurozone (constituted by the EU member states which have adopted the euro) has since grown to 19 countries.[171][p]

Since its launch the euro has become the second reserve currency in the world with a quarter of foreign exchanges reserves being in euro.[172] The euro, and the monetary policies of those who have adopted it in agreement with the EU, are under the control of the European Central Bank (ECB).[173]The Eurozone (blue) represents 338 million people. The euro is the second-largest reserve currency in the world.

The ECB is the central bank for the eurozone, and thus controls monetary policy in that area with an agenda to maintain price stability. It is at the centre of the European System of Central Banks, which comprehends all EU national central banks and is controlled by its General Council, consisting of the President of the ECB, who is appointed by the European Council, the Vice-President of the ECB, and the governors of the national central banks of all 28 EU member states.[174]

The European System of Financial Supervision is an institutional architecture of the EU's framework of financial supervision composed by three authorities: the European Banking Authority, the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority and the European Securities and Markets Authority. To complement this framework, there is also a European Systemic Risk Board under the responsibility of the ECB. The aim of this financial control system is to ensure the economic stability of the EU.[175]

To prevent the joining states from getting into financial trouble or crisis after entering the monetary union, they were obliged in the Maastricht treaty to fulfil important financial obligations and procedures, especially to show budgetary discipline and a high degree of sustainable economic convergence, as well as to avoid excessive government deficits and limit the government debt to a sustainable level.

Energy

Main article: Energy policy of the European UnionIn 2006, the EU-27 had a gross inland energy consumption of 1,825 million tonnes of oil equivalent (toe).[177] Around 46% of the energy consumed was produced within the member states while 54% was imported.[177] In these statistics, nuclear energy is treated as primary energy produced in the EU, regardless of the source of the uranium, of which less than 3% is produced in the EU.[178]

The EU has had legislative power in the area of energy policy for most of its existence; this has its roots in the original European Coal and Steel Community. The introduction of a mandatory and comprehensive European energy policy was approved at the meeting of the European Council in October 2005, and the first draft policy was published in January 2007.[179]

The EU has five key points in its energy policy: increase competition in the internal market, encourage investment and boost interconnections between electricity grids; diversify energy resources with better systems to respond to a crisis; establish a new treaty framework for energy co-operation with Russia while improving relations with energy-rich states in Central Asia[180] and North Africa; use existing energy supplies more efficiently while increasing renewable energy commercialisation; and finally increase funding for new energy technologies.[179]

The EU imports 82% of its oil, 57% of its natural gas[181] and 97.48% of its uranium[178] demands. Because of Europe's dependence on Russian energy the EU is attempting to diversify its energy supply.[182]

Infrastructure

Further information: European Commissioner for Transport, European Commissioner for Industry and Entrepreneurship, and European Investment BankThe EU is working to improve cross-border infrastructure within the EU, for example through the Trans-European Networks (TEN). Projects under TEN include the Channel Tunnel, LGV Est, the Fréjus Rail Tunnel, the Öresund Bridge, the Brenner Base Tunnel and the Strait of Messina Bridge. In 2010 the estimated network covers: 75,200 kilometres (46,700 mi) of roads; 78,000 kilometres (48,000 mi) of railways; 330 airports; 270 maritime harbours; and 210 internal harbours.[183][184]The Öresund Bridge between Denmark and Sweden is part of the Trans-European Networks.

Rail transport in Europe is being synchronised with the European Rail Traffic Management System (ERTMS), an initiative to greatly enhance safety, increase efficiency of trains and enhance cross-border interoperability of rail transport in Europe by replacing signalling equipment with digitized mostly wireless versions and by creating a single Europe-wide standard for train control and command systems.

The developing European transport policies will increase the pressure on the environment in many regions by the increased transport network. In the pre-2004 EU members, the major problem in transport deals with congestion and pollution. After the recent enlargement, the new states that joined since 2004 added the problem of solving accessibility to the transport agenda.[185] The Polish road network was upgraded such as the A4 autostrada.[186][187]

The Galileo positioning system is another EU infrastructure project. Galileo is a proposed Satellite navigation system, to be built by the EU and launched by the European Space Agency (ESA). The Galileo project was launched partly to reduce the EU's dependency on the US-operated Global Positioning System, but also to give more complete global coverage and allow for greater accuracy, given the aged nature of the GPS system.[188]

Agriculture

Main article: Common Agricultural PolicyThe Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is one of the long lasting policies of the European Community.[189] The policy has the objectives of increasing agricultural production, providing certainty in food supplies, ensuring a high quality of life for farmers, stabilising markets, and ensuring reasonable prices for consumers.[r] It was, until recently, operated by a system of subsidies and market intervention. Until the 1990s, the policy accounted for over 60% of the then European Community's annual budget, and as of 2013 accounts for around 34%.[190]Vineyards in Romania; EU farms are supported by the Common Agricultural Policy, the largest budgetary expenditure.

The policy's price controls and market interventions led to considerable overproduction. These were intervention stores of products bought up by the Community to maintain minimum price levels. To dispose of surplus stores, they were often sold on the world market at prices considerably below Community guaranteed prices, or farmers were offered subsidies (amounting to the difference between the Community and world prices) to export their products outside the Community. This system has been criticised for under-cutting farmers outside Europe, especially those in the developing world.[191] Supporters of CAP argue that the economic support which it gives to farmers provides them with a reasonable standard of living.[191]

Since the beginning of the 1990s, the CAP has been subject to a series of reforms. Initially, these reforms included the introduction of set-aside in 1988, where a proportion of farm land was deliberately withdrawn from production, milk quotas and, more recently, the 'de-coupling' (or disassociation) of the money farmers receive from the EU and the amount they produce (by the Fischler reforms in 2004). Agriculture expenditure will move away from subsidy payments linked to specific produce, toward direct payments based on farm size. This is intended to allow the market to dictate production levels.[189] One of these reforms entailed the abolition of the EU's sugar regime, which previously divided the sugar market between member states and certain African-Caribbean nations with a privileged relationship with the EU.[192]

Competition

Further information: European Union competition law and European Commissioner for CompetitionThe EU operates a competition policy intended to ensure undistorted competition within the single market.[s] The Commission as the competition regulator for the single market is responsible for antitrust issues, approving mergers, breaking up cartels, working for economic liberalisation and preventing state aid.[193]

The Competition Commissioner, currently Margrethe Vestager, is one of the most powerful positions in the Commission, notable for the ability to affect the commercial interests of trans-national corporations.[194] For example, in 2001 the Commission for the first time prevented a merger between two companies based in the United States (GE and Honeywell) which had already been approved by their national authority.[195] Another high-profile case against Microsoft, resulted in the Commission fining Microsoft over €777 million following nine years of legal action.[196]

Demographics

Main article: Demographics of the European UnionAs of 1 January 2015, the population of the European Union is about 508.2 million people.[7] In 2013, 5,075,000 live births were registered and 4,999,200 deaths. The net migration to the EU was +653,100. In 2010, 47.3 million people who lived in the EU were born outside their resident country. This corresponds to 9.4% of the total EU population. Of these, 31.4 million (6.3%) were born outside the EU and 16.0 million (3.2%) were born in another EU member state. The largest absolute numbers of people born outside the EU were in Germany (6.4 million), France (5.1 million), the United Kingdom (4.7 million), Spain (4.1 million), Italy (3.2 million), and the Netherlands (1.4 million).[197]

Urbanisation

The EU contains 16 cities with populations of over one million. Besides many large cities, the EU also includes several densely populated regions that have no single core but have emerged from the connection of several cities and now encompass large metropolitan areas. The largest are Rhine-Ruhr having approximately 11.5 million inhabitants (Cologne, Dortmund, Düsseldorf et al.), Randstad approx. 7 million (Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, Utrecht et al.), Frankfurt Rhine-Main approx. 5.8 million (Frankfurt, Wiesbaden et al.), the Flemish Diamond approx. 5.5 million (urban area in between Antwerp, Brussels, Leuven and Ghent), Upper Silesia approx. 5.3 million (Katowice, Ostrava) and Øresund approx. 3.7 million (Copenhagen, Malmö).[198]

Largest population centres of European Union

Larger Urban Zones, according to Eurostat[199][200]Rank City name State Pop.

London

Paris

1  London

LondonUnited Kingdom 11,905,500

Madrid

Berlin

2  Paris

ParisFrance 11,532,409 3  Madrid

MadridSpain 5,804,829 4  Berlin

BerlinGermany 4,971,331 5  Barcelona

BarcelonaSpain 4,440,629 6  Athens

AthensGreece 4,013,368 7  Rome

RomeItaly 3,457,690 8  Hamburg

HamburgGermany 3,134,620 9  Milan

MilanItaly 3,076,643 10  Katowice

KatowicePoland 2,710,397

Languages

Main article: Languages of the European Union

Among the many languages and dialects used in the EU, it has 24 official and working languages: Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, English, Estonian, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Hungarian, Italian, Irish, Latvian, Lithuanian, Maltese, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Slovak, Slovene, Spanish, and Swedish.[204][205] Important documents, such as legislation, are translated into every official language.Language Native speakers Total English 13% 51% German 16% 27% French 13% 24% Italian 12% 16% Spanish 8% 15% Polish 8% 9% Romanian 5% 5% Dutch 4% 5% Greek 3% 4% Hungarian 3% 3% Portuguese 2% 3% Czech 2% 3% Swedish 2% 3% Bulgarian 2% 2% Slovak 1% 2% Danish 1% 1% Finnish 1% 1% Lithuanian 1% 1% Croatian 1% 1% Slovenian <1 td=""> <1 td=""> Estonian <1 td=""> <1 td=""> Irish <1 td=""> <1 td=""> Latvian <1 td=""> <1 td=""> Maltese <1 td=""> <1 td=""> Survey 2012.[201]

Native: Native language[202]

Total: EU citizens able to hold a

conversation in this language[203]

The European Parliament provides translation into all languages for documents and its plenary sessions.[206] Some institutions use only a handful of languages as internal working languages.[207] Catalan, Galician, Basque, Scottish Gaelic and Welsh are not official languages of the EU but have semi-official status in that official translations of the treaties are made into them and citizens of the EU have the right to correspond with the institutions using them.

Language policy is the responsibility of member states, but EU institutions promote the learning of other languages.[t][208] English is the most widely spoken language in the EU, being spoken by 51% of the EU population when counting both native and non-native speakers.[209] German is the most widely spoken mother tongue, being spoken by 16% of the EU population. 56% of EU citizens are able to engage in a conversation in a language other than their mother tongue.[210] Most official languages of the EU belong to the Indo-European language family, except Estonian, Finnish, and Hungarian, which belong to the Uralic language family, and Maltese, which is a Semitic language. Most EU official languages are written in the Latin alphabet except Bulgarian, which is written in the Cyrillic alphabet, and Greek, which is written in the Greek alphabet.[211] These are the three official scripts of the European Union.[212]

Besides the 24 official languages, there are about 150 regional and minority languages, spoken by up to 50 million people.[211] Although EU programmes can support regional and minority languages, the protection of linguistic rights is a matter for the individual member states. The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages ratified by most EU states provides general guidelines that states can follow to protect their linguistic heritage.

The European Day of Languages is held annually on 26 September and is aimed at encouraging language learning across Europe.

Religion

The EU is a secular body with no formal connection to any religion. The Article 17 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union recognises the "status under national law of churches and religious associations" as well as that of "philosophical and non-confessional organisations".[214]

The preamble to the Treaty on European Union mentions the "cultural, religious and humanist inheritance of Europe".[214] Discussion over the draft texts of the European Constitution and later the Treaty of Lisbon included proposals to mention Christianity or God, or both, in the preamble of the text, but the idea faced opposition and was dropped.[215]

Christians in the EU are divided among members of Catholicism (both Roman and Eastern Rite), numerous Protestant denominations, and the Eastern Orthodox Church. In 2009, the EU had an estimated Muslim population of 13 million,[216] and an estimated Jewish population of over a million.[217] The other world religions of Buddhism, Hinduism and Sikhism are also represented in the EU population.

According to new polls about religiosity in the European Union in 2012 by Eurobarometer, Christianity is the largest religion in the European Union, accounting for 72% of the EU population.[213] Catholics are the largest Christian group, accounting for 48% of the EU population, while Protestants make up 12%, Eastern Orthodox make up 8% and other Christians make up 4%.[218]

Eurostat's Eurobarometer opinion polls showed in 2005 that 52% of EU citizens believed in a God, 27% in "some sort of spirit or life force", and 18% had no form of belief.[219] Many countries have experienced falling church attendance and membership in recent years.[220] The countries where the fewest people reported a religious belief were Estonia (16%) and the Czech Republic (19%).[219] The most religious countries were Malta (95%, predominantly Roman Catholic) as well as Cyprus and Romania (both predominantly Orthodox) each with about 90% of citizens professing a belief in God. Across the EU, belief was higher among women, older people, those with religious upbringing, those who left school at 15 or 16 and those "positioning themselves on the right of the political scale".[219]

Education and science

Main articles: Educational policies and initiatives of the European Union and Framework Programmes for Research and Technological DevelopmentBasic education is an area where the EU's role is limited to supporting national governments. In higher education, the policy was developed in the 1980s in programmes supporting exchanges and mobility. The most visible of these has been the Erasmus Programme, a university exchange programme which began in 1987. In its first 20 years, it has supported international exchange opportunities for well over 1.5 million university and college students and has become a symbol of European student life.[221]Erasmus Programme logo, representing the European student exchange.

There are now similar programmes for school pupils and teachers, for trainees in vocational education and training, and for adult learners in the Lifelong Learning Programme 2007–2013. These programmes are designed to encourage a wider knowledge of other countries and to spread good practices in the education and training fields across the EU.[222][223] Through its support of the Bologna Process, the EU is supporting comparable standards and compatible degrees across Europe.

Scientific development is facilitated through the EU's Framework Programmes, the first of which started in 1984. The aims of EU policy in this area are to co-ordinate and stimulate research. The independent European Research Council allocates EU funds to European or national research projects.[224] EU research and technological framework programmes deal in a number of areas, for example energy where the aim is to develop a diverse mix of renewable energy to help the environment and to reduce dependence on imported fuels.[225]

Health care

Further information: Healthcare in EuropeAlthough the EU has no major competences in the field of health care, Article 35 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union affirms that "A high level of human health protection shall be ensured in the definition and implementation of all Union policies and activities". The European Commission's Directorate-General for Health and Consumers seeks to align national laws on the protection of people's health, on the consumers' rights, on the safety of food and other products.[226][227][228]European Health Insurance Card.

(French version pictured)

Health care in the EU is provided through a wide range of different systems run at the national level. The systems are primarily publicly funded through taxation (universal health care). Private funding for health care may represent personal contributions towards meeting the non-taxpayer refunded portion of health care or may reflect totally private (non-subsidised) health care either paid out of pocket or met by some form of personal or employer funded insurance.[citation needed]

All EU and many other European countries offer their citizens a free European Health Insurance Card which, on a reciprocal basis, provides insurance for emergency medical treatment insurance when visiting other participating European countries.[229] A directive on cross-border healthcare aims at promoting co-operation on health care between member states and facilitating access to safe and high-quality cross-border healthcare for European patients.[230][231][232]

Culture

Cultural co-operation between member states has been a concern of the EU since its inclusion as a community competency in the Maastricht Treaty.[233] Actions taken in the cultural area by the EU include the Culture 2000 7-year programme,[233] the European Cultural Month event,[234] the MEDIA Programme,[235] and orchestras such as the European Union Youth Orchestra.[236]

The European Capital of Culture programme selects one or more cities in every year to assist the cultural development of that city.[237] 53 EU cities have been part of this initiative up to 2016.

Sport

Main articles: Sport policies of the European Union and Sport in EuropeSport is mainly the responsibility of the member states or other international organisations, rather than of the EU. However, there are some EU policies that have had an impact on sport, such as the free movement of workers, which was at the core of the Bosman ruling that prohibited national football leagues from imposing quotas on foreign players with European citizenship.[238] The Treaty of Lisbon requires any application of economic rules to take into account the specific nature of sport and its structures based on voluntary activity.[239] This followed lobbying by governing organisations such as the International Olympic Committee and FIFA, due to objections over the application of free market principles to sport, which led to an increasing gap between rich and poor clubs.[240] The EU does fund a programme for Israeli, Jordanian, Irish, and British football coaches, as part of the Football 4 Peace project.[241]

Association Football is the most popular sport in almost all EU countries. Club teams from the EU are the highest paid in the world. Other team sports like rugby, ice hockey, basketball, cricket, handball, volleyball and water polo are also popular in some member states.

Symbols

Main article: Symbols of EuropeThe flag of the Union consists of a circle of 12 golden stars on a blue background. The blue represents the West, while the number and position of the stars represent completeness and unity, respectively.[242] Originally designed in 1955 for the Council of Europe, the flag was adopted by the European Communities, the predecessors of the present Union, in 1986.Clockwise from top left: The European flag seen at the occasion of the 2004 enlargement; the reliquary bust of Charlemagne (c. 1350); Europa and the bull, depicted as the personification of Europe in a 1700 map.

United in Diversity was adopted as the motto of the Union in the year 2000, having been selected from proposals submitted by school pupils.[243] Since 1985, the flag day of the Union has been Europe Day, on 9 May (the date of the 1950 Schuman declaration). The anthem of the Union is an instrumental version of the prelude to the Ode to Joy, the 4th movement of Ludwig van Beethoven's ninth symphony. The anthem was adopted by European Community leaders in 1985 and has since been played on official occasions.[244]

Besides naming the continent, the Greek mythological figure of Europa has frequently been employed as a personification of Europe. Known from the myth in which Zeus seduces her in the guise of a white bull, Europa has also been referred to in relation to the present Union. Statues of Europa and the bull decorate several of the Union's institutions and a portrait of her is seen on the 2013 series of Euro banknotes. The bull is, for its part, depicted on all residence permit cards.[245]

Charles the Great, also known as Charlemagne (Latin: Carolus Magnus) and later recognized as Pater Europae ("Father of Europe"),[246][247][248][249][250] has a symbolic relevance to Europe. The Commission has named one of its central buildings in Brussels after Charlemagne and the city of Aachen has since 1949 awarded the Charlemagne Prize to champions of European unification.[251] Since 2008, the organisers of this prize, in conjunction with the European Parliament, have awarded the Charlemagne Youth Prize in recognition of similar efforts by young people.[252]

Media

Main articles: Media freedom in the European Union and Cinema of EuropeMedia freedom is a fundamental right that applies to all member states of the European Union and its citizens, as defined in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights as well as the European Convention on Human Rights.[253]:1 Within the EU enlargement process, guaranteeing media freedom is named a "key indicator of a country's readiness to become part of the EU".[254]

See also