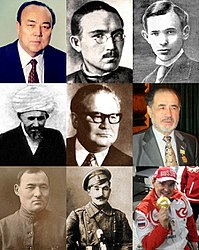

Oghuz Turks

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about a group of Turkic peoples. For other uses, see Oghuz.

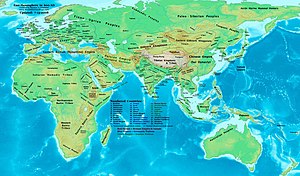

Oguz Yabgu State in Kazakhstan, 750-1055

In the 9th century, the Oguzes from the Aral steppes drove Bechens from the Emba and Ural River region toward the west. In the 10th century, they inhabited the steppe of the rivers Sari-su, Turgai, and Emba to the north of Lake Balkhash of modern-day Kazakhstan.[4] A clan of this nation, the Seljuks, embraced Islam and in the 11th century entered Persia, where they founded the Great Seljuk Empire. Similarly in the 11th century, a Tengriist Oghuz clan—referred to as Uzes or Torks in the Russian chronicles—overthrew Pecheneg supremacy in the Russian steppe. Harried by another Turkic horde, the Kipchaks, these Oghuz penetrated as far as the lower Danube, crossed it and invaded the Balkans, where they were either crushed[5] or struck down by an outbreak of plague, causing the survivors either to flee or to join the Byzantine imperial forces as mercenaries (1065).[6]

Asia in 600 AD

Linguistically, the Oghuz are listed together with the old Kimaks of the middle Yenisei of the Ob, the old Kipchaks who later emigrated to southern Russia, and the modern Kirghiz in one particular Turkic group, distinguished from the rest by the mutation of the initial y sound to j (dj).

"The term 'Oghuz' was gradually supplanted among the Turks themselves by Türkmen, 'Turcoman', from the mid 900's on, a process which was completed by the beginning of the 1200s."[8]

"The Ottoman dynasty, who gradually took over Anatolia after the fall of the Seljuks, toward the end of the 13th century, led an army that was also predominantly Oghuz."[9]

Contents

Origins

Main article: Origin of the Turks

In 178-177 BC, the Xiongnu shan-yü Mao-tun subdued a people called Hu-chieh, west of Wu-sun located in the Tarim Basin, the Ili Valley and the Pamir Mountains. It is suggested that the early pronunciation of this transliteration might be related to the ancestors of Oghur/Oghuz.[10] However, it is known that Oghuz people historically appeared with this name in a region extending from the east of Caspian Sea to the east of Lake Aral, neighbouring to Karakum Desert in the south.[11]

A head of Dede Korkut in Baku.

According to many historians, the usage of the word "Oghuz" is dated back to the advent of the Huns (220 BC). The title of "Oghuz" (Oguz Kaan) was given to Mau-Tun,[13][14] the founder of the Xiongnu Empire, which is often considered the first Turkic political entity in Central Asia.

Also in the 2nd century BC, a Turkic tribe called O-kut or Wuqi 呼揭, 呼得, 乌揭, 乌护 who were described as a western enemy of the Huns (referred to in Chinese sources, Shiji, 110 and Suishu, 84) were mentioned in the area of the Irtysh River, in present-day Lake Zaysan. The Greek sources used the name Oufi (or Ouvvi) to describe the Oghuz Turks, a name they had also used to describe the Huns centuries earlier.[citation needed]

A number of tribal groupings bearing the name Oghuz, often with a numeral representing the number of united tribes in the union, are noted.

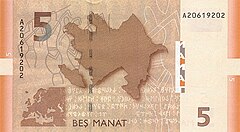

Reverse side of Azerbaijani manat showing the old Turkic script.

Prior to the Göktürk state, there are references to the Sekiz-Oghuz ("eight-Oghuz") and the Dokuz-Oghuz ("nine-Oghuz") union. The Oghuz Turks under Sekiz-Oghuz and the Dokuz-Oghuz state formations ruled different areas in the vicinity of the Altay mountains. During the establishment of the Göktürk state, Oghuz tribes inhabited the Altay mountain region and also lived in northeastern areas of the Altay mountains along the Tula River. They were also present as a community near the Barlik River in present-day northern Mongolia.

Their main homeland and domain in the ensuing centuries was the area of Transoxiana, in western Turkestan.

This land became known as the "Oghuz steppe", which is an area between the Caspian and Aral Seas. Ibn al-Athir, an Arab historian, declared that the Oghuz Turks had come to Transoxiana in the period of the caliph Al-Mahdi in the years between 775 and 785. In the period of the Abbasid caliph Al-Ma'mun (813–833), the name Oghuz starts to appear in the works of Islamic writers. By 780, the eastern parts of the Syr Darya were ruled by the Karluk Turks and the western region (Oghuz steppe) was ruled by the Oghuz Turks.

Social units

In Oghuz traditions, "society was simply the result of the growth of individual families". But such a society also grew by alliances and the expansion of different groups, normally through marriages. The shelter of the Oghuz tribes was a tent-like dwelling, erected on wooden poles and covered with skin, felt, or hand-woven textiles, which is called a yurt.

Their cuisine included yahni (stew), kebabs, Toyga çorbası (lit. "wedding soup;" a soup made from wheat flour and yogurt), Kımız (a traditional drink of the Turks, made from fermented horse milk), Pekmez (a syrup made of boiled grape juice) and helva made with wheat starch or rice flour, tutmac (noodle soup), yufka (flattened bread), katmer (layered pastry), chorek (ring-shaped buns), bread, clotted cream, cheese, milk and ayran (diluted yogurt beverage), as well as wine.

Social order was maintained by emphasizing "correctness in conduct as well as ritual and ceremony". Ceremonies brought together the scattered members of the society to celebrate birth, puberty, marriage, and death. Such ceremonies had the effect of minimizing social dangers and also of adjusting persons to each other under controlled emotional conditions.

Patrilineally related men and their families were regarded as a group with rights over a particular territory and were distinguished from neighbours on a territorial basis. Marriages were often arranged among territorial groups so that neighbouring groups could become related, but this was the only organizing principle that extended territorial unity. Each community of the Oghuz Turks was thought of as part of a larger society composed of distant as well as close relatives. This signified "tribal allegiance". Wealth and materialistic objects were not commonly emphasized in Oghuz society and most remained herders, and when settled they would be active in agriculture.

Status within the family was based on age, gender, relationships by blood, or marriageability. Males as well as females were active in society, yet men were the backbones of leadership and organization. According to the Book of Dede Korkut, which demonstrates the culture of the Oghuz Turks, women were "expert horse riders, archers, and athletes". The elders were respected as repositories of both "secular and spiritual wisdom".

Homeland in Transoxiana

Physical map of Central Asia from the Caucasus in the northwest, to Mongolia in the northeast.

In his accredited work titled Diwan Lughat al-Turk, Mahmud of Kashgar, a Turkic scholar of the 11th century, described the Karachuk Mountains which are located just east of the Aral Sea as the original homeland of the Oghuz Turks. The Karachuk mountains are now known as the Tengri Tagh (Tian Shan in Chinese) Mountains, and they are adjacent to Syr Darya.

The extension from the Karachuk Mountains towards the Caspian Sea (Transoxiana) was called the "Oghuz Steppe Lands" from where the Oghuz Turks established trading, religious and cultural contacts with the Abbasid Arab caliphate who ruled to the south. This is around the same time that they first converted to Islam and renounced their Tengriism belief system. The Arab historians mentioned that the Oghuz Turks in their domain in Transoxiana were ruled by a number of kings and chieftains.

It was in this area that they later founded the Seljuk Empire, and it was from this area that they spread west into western Asia and eastern Europe during Turkic migrations from the 9th until the 12th century. The founders of the Ottoman Empire were also Oghuz Turks.

Oghuz and Yörüks

Main article: Yörüks

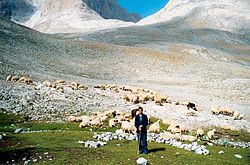

Yörük shepherd in the Taurus Mountains.

Main areas inhabited by Yörük tribes in Anatolia today[citation needed]

Oghuz Turk dynasties

The Ak Koyunlu Confederation in 1478

- Seljuks

- Aq Qoyunlu

- Kara Koyunlu

- Afsharids

- Ottomans

- Qajars

- Artuqids

- Safavid dynasty

- Zengid dynasty

- Anatolian beyliks

- Mengujekids

Traditional tribal organization

- Kayı[24] (founders of the Ottoman dynasty and Jandarids)

- Bayat (founders of the Qajar dynasty, Dulkadirids, Fuzûlî)

- Alkaevli

- Karaevli

- Yazır

- Döger (founders of the Artuqid dynasty)

- Dodurga

- Yaparlı

- Afshar (Afşar; founders of the Afsharid dynasty Nader Shah)

- Kızık

- Begdili

- Kargın

- Bayandur (founders of the Ak Koyunlu)

- Pecheneg

- Çavuldur[25]

- Chepni

- Salur (Kadi Burhan al-Din and Salgurlular State in Iraq and Karamanid dynasty; also refer to Salar people)

- Eymür

- Alayuntlu

- Yüreğir (founders of the Ramadanid dynasty)

- İgdir

- Büğdüz

- Yıva (Qara Qoyunlu , Oguzs Yabgus dynasty)

- Kınık (founders of the Seljuk Empire)[26]

Turcoman Turkman

A Turkmen man of Central Asia in traditional clothes, around 1905–1915.

For example, many sources prior to the modern age claim that the largest component of the population of Azerbaijan is composed of "Turcoman tribes". The "Turkmen" reference in history books which is often used for Azerbaijanis and Turks of Turkey simply means "Muslim Turk" or "Muslim western Turk", which means Oghuz Turk. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, the name Turkmen is a synonym of Oghuz.[citation needed] Turkish historian Yılmaz Öztuna presents almost the same definition of the name "Turkmen". He labels the Turkmen Oghuz or western Turkish populations as Ottomans, Azerbaijan, and Turkmen (Turkmenistan).[citation needed] In Turkey the word "Turkmen" refers to nomadic Turkish tribes (all Muslims), some of whom still continue this lifestyle.[citation needed]

Literature

Oghuz Turkish literature includes the famous Book of Dede Korkut which was UNESCO's 2000 literary work of the year, as well as the Oguznama and Köroğlu epics which are part of the literary history of Azerbaijanis, Turks of Turkey and Turkmens. The modern and classical literature of Azerbaijan, Turkey and Central Asia are also considered Oghuz literature, since it was produced by their descendants.The Book of Dede Korkut is an invaluable collection of epics and stories, bearing witness to the language, the way of life, religions, traditions and social norms of the Oghuz Turks in Azerbaijan, Turkey and Central Asia.

See also

- Afshar dynasty

- Gokturks

- Kimek

- Oghuz languages

- Gagauz people

- Salar people

- Tokuz-Oguzes

- Oghuz Khan

- Mythology of the Turkic and Mongolian peoples

- Timeline of Turks (500-1300)

- Pechenegs

Notes

- Kafesoğlu, İbrahim. Türk Milli Kültürü. Türk Kültürünü Araştırma Enstitüsü, 1977. page 134

References

- Grousset, R., The Empire of the Steppes, 1991, Rutgers University Press

- Nicole, D., Attila and the Huns, 1990, Osprey Publishing

- Lewis, G., The Book of Dede Korkut, "Introduction", 1974, Penguin Books

- Minahan, James B. One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Press, 2000. page 692

- Aydın, Mehmet. Bayat-Bayat boyu ve Oğuzların tarihi. Hatiboğlu Yayınevi, 1984. web page

External links

- The Book of Dede Korkut (pdf format) at the Uysal-Walker Archive of Turkish Oral Narrative

- Similarities between the epics of Dede Korkut and Alpamysh

- A page dedicated to Oguz Khan

- The Old Turkic Inscriptions.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oghuz Turks. |

Pechenegs

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the Turkic tribe. For the Russian weapon, see Pecheneg machine gun.

| Pecheneg Khanates | |||||

| Peçenek Hanlığı | |||||

| Khanate | |||||

|

|||||

|

Pecheneg Khanates and neighboring territories, c.1015

|

|||||

| Capital | Not specified | ||||

| Languages | Pecheneg Turkic | ||||

| Political structure | Khanate | ||||

| History | |||||

| • | Established | 860 | |||

| • | Disestablished | 1091 | |||

|

History of the Turkic peoples Pre-14th century |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turkic Khaganate 552–744 | |||||||

| Western Turkic | |||||||

| Eastern Turkic | |||||||

| Avar Khaganate 564–804 | |||||||

| Khazar Khaganate 618–1048 | |||||||

| Xueyantuo 628–646 | |||||||

| Great Bulgaria 632–668 | |||||||

| Danube Bulgaria | |||||||

| Volga Bulgaria | |||||||

| Kangar union 659–750 | |||||||

| Turgesh Khaganate 699–766 | |||||||

| Uyghur Khaganate 744–840 | |||||||

| Karluk Yabgu State 756–940 | |||||||

| Kara-Khanid Khanate 840–1212 | |||||||

| Western Kara-Khanid | |||||||

| Eastern Kara-Khanid | |||||||

| Gansu Uyghur Kingdom 848–1036 | |||||||

| Kingdom of Qocho 856–1335 | |||||||

| Pecheneg Khanates 860–1091 |

Kimek Khanate 743–1035 |

||||||

| Cumania 1067–1239 |

Oghuz Yabgu State 750–1055 |

||||||

| Ghaznavid Empire 963–1186 | |||||||

| Seljuk Empire 1037–1194 | |||||||

| Seljuk Sultanate of Rum | |||||||

| Khwarazmian Empire 1077–1231 | |||||||

| Delhi Sultanate 1206–1526 | |||||||

| Mamluk dynasty | |||||||

| Khilji dynasty | |||||||

| Tughlaq dynasty | |||||||

| Golden Horde | [1][2][3] 1240s–1502 | |||||||

| Mamluk Sultanate (Cairo) 1250–1517 | |||||||

| Bahri dynasty | |||||||

| Ottoman Empire 1299-1923 | |||||||

Contents

Ethnonym

The Pechenegs' ethnonym derived from the Old Turkic word for "brother-in-law” (baja, baja-naq or bajinaq), implying that it initially referred to "in-law related clan or tribe".[5][6] Sources written in different languages used similar denominations when referring to the confederation of the Pecheneg tribes.[5] They were mentioned under the names Bjnak, Bjanak or Bajanak in Arabic and Persian texts, as Be-ča-nag in Classical Tibetan documents, as Pačanak-i in works written in Georgian, and as Pacinnak in Armenian.[5] Anna Komnene and other Byzantine authors referred to the Pechenegs as Patzinakoi or Patzinakitai.[5] In medieval Latin texts, the Pechenegs were referred to as Pizenaci, Bisseni or Bessi.[5] East Slavic peoples use the terms Pečenegi or Pečenezi, while the Poles mentions them as Pieczyngowie or Piecinigi.[5] The Hungarian word for Pecheneg is besenyő.[5]According to Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, three of the eight Pechenegs "provinces" or clans were known under the name Kangar.[7] He added that they received this denomination because "they are more valiant and noble than the rest" of the people "and that is what the title Kangar signifies".[7][8] However, no Turkic word with the meaning suggested by the emperor has been demonstrated.[9] Ármin Vámbéry connected the Kangar denomination to the Kirghiz words kangir ("agile"), kangirmak ("to go out riding") and kani-kara ("black-blooded"), while Carlile Aylmer Macartney associated it with the Chagatai word gang ("chariot").[10] Omeljan Pritsak proposed that the name had initially been a composite term (Kängär As) deriving from the Tocharian word for stone (kank) and the Iranian ethnonym As.[11] If the latter assumption is valid, the ethnonym of the three Kangar tribes suggest that Iranian elements contributed to the formation of the Pecheneg people.[12]

Language

Main article: Pecheneg language

Mahmud al-Kashgari,

an 11th-century man of letters specialized in Turkic dialects argued

that the language spoken by the Pechenegs was a variant of the Cuman and Oghuz idioms.[13]

He suggested that foreign influences on the Pechenegs gave rise to

phonetical differences between their tongue and the idiom spoken by

other Turkic peoples.[14] Anna Komnene likewise stated that the Pechenegs and the Cumans shared a common language.[13] Although the Pecheneg language itself died out centuries ago,[15] the names of the Pecheneg "provinces" recorded by Constantine Porphyrogenitus prove that the Pechenegs spoke a Turkic language.[16]History

Origins (till c. 800 or 850)

Ibn Khordadbeh, Mahmud al-Kashgari, Muhammad al-Idrisi and many other Muslim scholars agreed that the Pechenegs belonged to the Turkic peoples.[17] The Russian Primary Chronicle stated that the "Torkmens, Pechenegs, Torks, and Polovcians" descended from "the godless sons of Ishmael, who had been sent as a chastisement to the Christians".[18][19]Paul Pelliot was the first to propose that a 7th-century Chinese work, the Book of Sui preserved the earliest record on the Pechenegs.[20] It writes of the Pei-ju, a people settled along the En-ch'u and A-lan peoples (identified as the Onogurs and Alans, respectively) east of Fu-lin (the Eastern Roman Empire).[21] In contrast with this view, Victor Spinei argues that the first certain reference to the Pechenegs can be read in a Tibetan translation of an 8th-century Uyghur text.[21] It narrates a war between two peoples, the Be-ča-nag (the Pechenegs) and the Hor (the Ouzes).[21] The Pechenegs inhabited the region along the river Syr Darya at the time when the first records were made of them.[22][21]

Westward migration (c. 800 or 850–c. 895)

The Pechenegs were forced to leave their Central Asian homeland[6][21] by a coalition of the Oghuz Turks, Karluks and Kimaks.[11] The Pechenegs' westward migration started between the 790s and 850s, but its exact date cannot be determined.[6][21][11] The Pechenegs settled in the steppe corridor[23] between the rivers Ural and Volga.[21]According to Gardizi and other Muslim scholars who based their works on 9th-century sources, the Pechenegs' new territories were bordered by the Cumans, Khazars, Oghuz Turks and Slavs.[24][23] The same sources also narrate that the Pechenegs regularly waged war against the Khazars and the latter's vassals, the Burtas.[23][25] The Khazars and the Oghuz Turks made an alliance against the Pechenegs and attacked them.[21][26] Outnumbered by the enemy, the Pechenegs started a new migration, invaded the dwelling places of the Hungarians and forced them to leave.[26][23] There is no consensual date for this second migration of the Pechenegs: Pritsak argues that it took place around 830,[23] but Kristó suggests that it could hardly occur before the 850s.[27] The Pechenegs settled along the rivers Donets and Kuban.[23]

It is plausible that the distinction between the "Turkic Pechenegs" and "Khazar Pechenegs" mentioned in the 10th-century Hudud al-'alam had its origin in this period.[23] Spinei proposes that the latter denomination most probably refers to Pecheneg groups accepting Khazar suzerainty.[21] In addition to these two branches, a third group of Pechenegs existed in this period: Constantine Porphyrogenitus and Ibn Fadlan mention that those who decided not to leave their homeland were incorporated into the Oghuz federation of Turkic tribes.[6][23] However, it is uncertain whether this groups' formation is connected to the Pechenegs' first or second migration (as it is proposed by Pritsak and Golden, respectively).[6][23] According to Mahmud al-Kashgari, one of the Üçok clans of the Oghuz Turks[28] was still formed by Pechenegs in the 1060s.[23]

Originally, the Pechenegs had their dwelling on the river Atil, and likewise on the river Geïch, having common frontiers with the Chazars and the so-called Uzes. But fifty years ago the so-called Uzes made common cause with the Chazars and joined battle with the Pechenegs and prevailed over them and expelled them from their country, which the so-called Uzes have occupied till this day. [...] At the time when the Pechenegs were expelled from their country, some of them of their own will and personal decision stayed behind there and united with the so-called Uzes, and even to this day they live among them, and wear such distinguishing marks as separate them off and betray their origin and how it came about that they were split off from their own folk: for their tunics are short, reaching to the knee, and their sleeves are cut off at the shoulder, whereby, you see, they indicate that they have been cut off from their own folk and those of their race.

Origins and area

In Mahmud Kashgari's 11th-century work Dīwān lughāt al-turk (Arabic: ديوان لغات الترك),[30] the name Beçenek is given two meanings. The first is "a Turkish nation living around the country of the Rum", where Rum was the Turkish word for the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire). Kashgari's second definition of Beçenek is "a branch of Oghuz Turks"; he subsequently described the Oghuz as being formed of 22 branches, of which the 19th branch was named Beçenek. Max Vasmer derives this name from the Turkic word for "brother-in-law, relative" (Turkmen: bacanak and Turkish: bacanak).By the 9th and 10th centuries, they controlled much of the steppes of southwestern Eurasia and the Crimean Peninsula. Although an important factor in the region at the time, like most nomadic tribes their concept of statecraft failed to go beyond random attacks on neighbours and spells as mercenaries for other powers.

According to Constantine Porphyrogenitus, writing in c. 950, Patzinakia, the Pecheneg realm, stretched west as far as the Siret River (or even the Eastern Carpathian Mountains), and was four days distant from "Tourkias" (i.e. Hungary).

The whole of Patzinakia is divided into eight provinces with the same number of great princes. The provinces are these: the name of the first province is Irtim; of the second, Tzour; of the third, Gyla; of the fourth, Koulpeï; of the fifth, Charaboï; of the sixth, Talmat; of the seventh, Chopon; of the eighth, Tzopon. At the time at which the Pechenegs were expelled from their country, their princes were, in the province of Irtim, Baïtzas; in Tzour, Kouel; in Gyla, Kourkoutai; in Koulpeï, Ipaos; in Charaboï, Kaïdoum; in the province of Talmat, Kostas; in Chopon, Giazis; in the province of Tzopon, Batas.According to Omeljan Pritsak, the Pechenegs are descendants from the ancient Kangars who originate from Tashkent.

In Armenian sources

In the Armenian chronicles of Matthew of Edessa Pechenegs are mentioned a couple of times. The first mention is in chapter 75, where it says that in the year 499 (according to the old Armenian calendar — years 1050–51 according to the Gregorian calendar) the Badzinag nation caused great destruction in many provinces of "Rome", i.e. the Byzantine territories. The second is in chapter 103, which is about the Battle of Manzikert. In that chapter it is told that the allies of "Rome", Padzunak and Uz (some branches of the Oghuz Turks) tribes which changed their sides at the peak of the battle and began fighting against the Byzantine forces, side by side with the Seljuq Turks. In the 132nd chapter a war between "Rome" and the Padzinags is described and after the defeat of the Roman (Byzantine) Army, an unsuccessful siege of Constantinople by the Padzinags is mentioned. In that chapter, the Patzinags are described as an "all archer army". In chapter 299, the Armenian prince, Vasil, who was in the Roman Army, sent a platoon of Padzinags (they had settled in the city of Misis, around modern Adana, which is far away from the lands where Pechenegs were then mainly living) to the aid of the Christians.Alliance with Byzantium

Sviatoslav enters Bulgaria with Pecheneg allies,[32] from the Constantine Manasses Chronicle.

The Uzes, another Turkic steppe people, eventually expelled the Pechenegs from their homeland; in the process, they also seized most of their livestock and other goods. An alliance of Oghuz, Kimeks, and Karluks was also pressing the Pechenegs, but another group, the Samanids, defeated that alliance. Driven further west by the Khazars and Cumans by 889, the Pechenegs in turn drove the Magyars west of the Dnieper River by 892.

Bulgarian Tsar Simeon I employed the Pechenegs to help fend off the Magyars. The Pechenegs were so successful that they drove out the Magyars remaining in Etelköz and the Pontic steppes, forcing them westward towards the Pannonian plain, where they later founded the Hungarian state.

Late history and decline

In the 9th century the Pechenegs began a period of wars against Kievan Rus'. For more than two centuries they had launched raids into the lands of Rus', which sometimes escalated into full-scale wars (like the 920 war on the Pechenegs by Igor of Kiev, reported in the Primary Chronicle). The Pecheneg wars against Kievan Rus' caused the Slavs from Walachian territories to gradually migrate north of the Dniestr in the 10th and 11th centuries.[33] Rus'/Pecheneg temporary military alliances also occurred however, as during the Byzantine campaign in 943 led by Igor.[34] In 968 the Pechenegs attacked and besieged Kiev; some joined the Prince of Kiev, Sviatoslav I, in his Byzantine campaign of 970–971, though eventually they ambushed and killed the Kievan prince in 972. According to the Primary Chronicle, the Pecheneg Khan Kurya made a chalice from Sviatoslav's skull, in accordance with the custom of steppe nomads. The fortunes of the Rus'-Pecheneg confrontation swung during the reign of Vladimir I of Kiev (990–995), who founded the town of Pereyaslav upon the site of his victory over the Pechenegs,[35] followed by the defeat of the Pechenegs during the reign of Yaroslav I the Wise in 1036. Shortly thereafter, other nomadic peoples replaced the weakened Pechenegs in the Pontic steppe: the Cumans and the Torks. According to Mykhailo Hrushevsky (History of Ukraine-Ruthenia), after its defeat near Kiev the Pecheneg Horde moved towards the Danube, crossed the river, and disappeared out of the Pontic steppes.

The Pechenegs slaughter the "skyths" of Sviatoslav I of Kiev.

In the 12th century, according to Byzantine historian John Kinnamos, the Pechenegs fought as mercenaries for the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos in southern Italy against the Norman king of Sicily, William the Bad.[37] A group of Pechenegs was present at the battle of Andria in 1155.[38]

The Pechenegs were last mentioned in 1168 as members of Turkic tribes known in the chronicles as the "Black Hats".[39]

In 15th-century Hungary, some people adopted the surname Besenyö (Hungarian for "Pecheneg"); they were most numerous in the county of Tolna. One of the earliest introductions of Islam into Eastern Europe came about through the work of an early 11th-century Muslim prisoner who was captured by the Byzantines. The Muslim prisoner was brought into the Besenyö territory of the Pechenegs, where he taught and converted individuals to Islam.[40] In the late 12th century, Abu Hamid al Garnathi referred to Hungarian Pechenegs - probably Muslims - living disguised as Christians. In the southeast of Serbia, there is a village called Pecenjevce founded by Pechenegs. After war with Byzantium, the broken remnants of the tribes found refuge in the area, where they established their settlement.

Leaders

See also

- Turkic peoples

- Timeline of Turks (500-1300)

- List of Turkic dynasties and countries

- Turkic peoples

- Oghuz (disambiguation)

- Kipchaks

- Kankalis

- Petržalka (Slovakia)

- Chepni another "Üçok" tribe.

- Cumans

- Khazars

- Bulgars

Footnotes

References

Primary sources

- Anna Comnena: The Alexiad (Translated by E. R. A. Sewter) (1969). Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044958-7.

- Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (Greek text edited by Gyula Moravcsik, English translation b Romillyi J. H. Jenkins) (1967). Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 0-88402-021-5.

Secondary sources

- Atalay, Besim (2006). Divanü Lügati't - Türk. Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi. ISBN 975-16-0405-2.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500-1250. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89452-4.

- Golden, Peter B. (2003). Nomads and their Neighbours in the Russian Steppe: Turks, Khazars and Quipchaqs. Ashgate. ISBN 0-86078-885-7.

- Macartney, C. A. (1968). The Magyars in the Ninth Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-08070-5.

- Pritsak, Omeljan (1975). "The Pechenegs: A Case of Social and Economic Transformation". Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi (The Peter de Ridder Press) 1: 211–235.

- Róna-Tas, András (1999). Hungarians and Europe in the Early Middle Ages: An Introduction to Early Hungarian History (Translated by Nicholas Bodoczky). CEU Press. ISBN 978-963-9116-48-1.

- Spinei, Victor (2003). The Great Migrations in the East and South East of Europe from the Ninth to the Thirteenth Century (Translated by Dana Badulescu). ISBN 973-85894-5-2.

- Spinei, Victor (2009). The Romanians and the Turkic Nomads North of the Danube Delta from the Tenth to the Mid-Thirteenth century. Koninklijke Brill NV. ISBN 978-90-04-17536-5.

Further reading

- (Russian) Golubovsky Peter V. (1884) Pechenegs, Torks and Cumans before the invasion of the Tatars. History of the South Russian steppes 9th-13th centuries (Печенеги, Торки и Половцы до нашествия татар. История южно-русских степей IX—XIII вв.) at Runivers.ru in DjVu format

- Pálóczi-Horváth, A. (1989). Pechenegs, Cumans, Iasians: Steppe peoples in medieval Hungary. Hereditas. Budapest: Kultúra [distributor]. ISBN 963-13-2740-X

- Pritsak, O. (1976). The Pečenegs: a case of social and economic transformation. Lisse, Netherlands: The Peter de Ridder Press.

External links

Categories:

- Former countries in Europe

- States and territories established in the 860s

- States and territories disestablished in 1091

- Historical Turkic states

- Turkic states

- Turkic dynasties

- History of the Turkic peoples

- Turkic peoples

- Turkic tribes

- Kievan Rus'

- Medieval Hungary

- Ethnic groups in Hungary

- Islam in Hungary

- Nomadic groups in Eurasia

- Pechenegs

- Moldova in the Early Middle Ages

- Romania in the Early Middle Ages

- Late Byzantine-era tribes in the Balkans

|coauthors= (help)Pechenegs: Wikipedia

Bashkirs

Bashkirs

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Bashkir (disambiguation).

| This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2012) |

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| approx. 2 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 1,584,554[2] | |

| 17,263[3] | |

| Languages | |

| Bashkir, Russian[4] | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam,[5][6] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Volga Tatars, Kazakhs | |

Most Bashkirs speak the Bashkir language, which belongs to the Kypchak branch of the Turkic languages and share cultural affinities with the broader Turkic peoples. In religion the Bashkirs are mainly Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi madhhab.

Contents

Ethnonym

There are several theories regarding the etymology of the endonym Bashqort.- Ethnologist R. G. Kuzeev defines the ethnonym as emanating from "bash" — "main, head" and "qort" — " clan, tribe".

- According to the theory of 18th-century ethnographers V. N. Tatishchev, P. I. Richkov, and Johann Gottlieb Georgi, the word "Bashqort" means "wolf-leader of the pack" (bash — "main",qort — "wolf").

- In 1847, the historian V. S. Yumatov suggested the meaning as "beekeeper, beemaster".

- Russian historian and ethnologist A. E. Alektorov in 1885 suggested that "Bashqort" means "distinct nation".

- The Turkologist N. A. Baskakov believed that the word "Bashqort" consists of two parts: "badz(a)" – brother-in-law" and "(o)gur" and means "Ugrics' brother-in-law".

- The historian and archaeologist Mikhail Artamonov has identified the Scythian tribe Bušxk' (or Bwsxk) with the ethnonym of modern Bashkirs. Historian R.H. Hewsen, however, rejects Artamanov's identification and instead identifies the Scythian Bušxk with the Volga Bulgars who were the estern neighbors of the Bashkirs at that time.[7]

- Ethnologist N. V. Bikbulatov's theory states that the term originates from the name of legendary Khazar warlord Bashgird, who was dwelling with two thousand of his warriors in the area of the Jayıq river.

- According to Douglas Morton Dunlop: the word "Bashqort" comes from beshgur (or bashgur) which means "five tribes" and, since -sh- in the modern Bashkir language parallels -l- in Bulgar, the names Bashgur and Bulgar are equivalent.

- Historian and linguist András Róna-Tas believes the ethonym "Bashkir" is a Bulgar Turkic reflex of the Hungarian self-denomination "Magyar" (Old Hungarian: "Majer").

- Recent ethnographic material collected from the Hormozgan province of Iran has led to the assumption of a possible phonetic relation btween the ethnonym Bashkardi with the selfname of the Bashkirs, giving reasons to suggest ancient Iranian stratum in the Bashkir culture [see for Bashkardi people#Ethnonym & ethnic connections].

History

Map of Europe, 600 AD

Mausoleum of Huseynbek, first Islamic religious leader of Historical Bashkortostan. 14th-century building

Middle Ages

Early records on the Bashkirs are found in medieval works by Sallam Tardzheman (9th century) and Ibn-Fadlan (10th century). Al-Balkhi (10th century) described Bashkirs as a people divided into two groups, one inhabiting the Southern Urals, the second group living on the Danube plain near the boundaries of Byzantium——therefore – given the geography and date – referring to either Danube Bulgars or Magyars. Ibn Rustah, a contemporary of Al Balkhi, observed that Bashkirs were an independent people occupying territories on both sides of the Ural mountain ridge between Volga, Kama, and Tobol Rivers and upstream of the Yaik river.Achmed ibn-Fadlan visited Volga Bulgaria as a staff member in the embassy of the Caliph of Baghdad in 922. He described them as a belligerent Turk nation. Ibn-Fadlan described the Bashkirs as nature worshipers, identifying their deities as various forces of nature, birds and animals. He also described the religion of acculturated Bashkirs as a variant of Tengrism, including 12 'gods' and naming Tengri – lord of the endless blue sky.

The first European sources to mention the Bashkirs are the works of Joannes de Plano Carpini and William of Rubruquis in the mid-13th century. These travelers, encountering Bashkir tribes in the upper parts of the Ural River, called them Pascatir or Bastarci, and asserted that they spoke the same language as the Hungarians.

During the 10th century, Islam spread among the Bashkirs. By the 14th century, Islam had become the dominant religious force in Bashkir society.

By 1236, Bashkortostan was incorporated into the empire of Genghis Khan.

During the 13th and 14th centuries, all of Bashkortostan was part of the Golden Horde. The brother of Batu-Khan, Sheibani, received the Bashkir lands to the east of the Ural Mountains – at that time inhabited by the ancestors of contemporary Kurgan Bashkirs.[citation needed]

During the period of Mongolian-Tatar dominion, some of the Bashkirs became subjects of the Kipchaks.[citation needed] Under the Golden Horde, they were subjected to different elements of the Mongols.[citation needed] After the breakup of the Mongol Empire, the Bashkirs were split between the Kazan Khanate, the Nogay Horde, and Siberian Khanate.[citation needed]

Early modern period

Bashkir women dressed in dulbega breast cover and kashmau headdress. 1770–1771.

In the middle of the 16th century, Bashkirs joined the Russian state. Previously they formed parts of the Nogai, Kazan, Sibir, and partly, Astrakhan khanates. Charters of Ivan the Terrible to Bashkir tribes became the basis of their contractual relationship with the tsar’s government. Primary documents pertaining to the Bashkirs during this period have been lost, some are mentioned in the (shezhere) family trees of the Bashkir.

The Bashkirs rebelled in 1662–64 and 1675–83 and 1705–11. In 1676, the Bashkirs rebelled under a leader named Seyid Sadir or 'Seit Sadurov', and the Russian army had great difficulties in ending the rebellion. The Bashkirs rose again in 1707, under Aldar and Kûsyom, on account of ill-treatment by the Russian officials.

1735 Bashkir War

The main settlement area of the Bashkirs in the late 18th century extends over the Kama, Volga, Samara and Tobol Rivers

Bashkir officers, 1838–1845

Kirillov's plan was approved on May 1, 1734 and he was placed in command. He was warned that this would provoke a Bashkir rebellion, but the warnings were ignored. He left Ufa with 2,500 men in 1735 and fighting started on the first of July. The war consisted of many small raids and complex troop movements, so it cannot be easily summarized. For example: In the spring of 1736 Kirillov burned 200 villages, killed 700 in battle and executed 158. An expedition of 773 men left Orenburg in November and lost 500 from cold and hunger. During, at Seiantusa the Bashkir planned to massacre sleeping Russian. The ambush failed. One thousand villagers, including women and children, were put to the sword and another 500 driven into a storehouse and burned to death. Raiding parties then went out and burned about 50 villages and killed another 2,000. Eight thousand Bashkirs attacked a Russian camp and killed 158, losing 40 killed and three prisoners who were promptly hanged. Rebellious Bashkirs raided loyal Bashkirs. Leaders who submitted were sometimes fined one horse per household and sometimes hanged.

Bashkirs fought on both sides (40% of 'Russian' troops in 1740). Numerous leaders rose and fell. The oddest was Karasakal or Blackbeard who pretended to have 82,000 men on the Aral Sea and had his followers proclaim him 'Khan of Bashkiria'. His nose had been partly cut off and he had only one ear. Such mutilations are standard Imperial punishments. The Kazakhs of the Little Horde intervened on the Russian side, then switched to the Bashkirs and then withdrew. Kirillov died of disease during the war and there were several changes of commander. All this was at the time of Empress Anna of Russia and the Russo-Turkish War (1735–1739).

Although the history of the 1735 Bashkir War cannot be easily summarized, its results can be.

- The Russian Imperial goal of expansion into Central Asia was delayed to deal with the Bashkir problem.

- Bashkiria was pacified in 1735–1740.

- Orenburg was established.

- The southern side of Bashkiria was fenced off by the Orenburg Line of forts. It ran from Samara on the Volga east up the Samara River to its headwaters, crossed to the middle Ural River and followed it east and then north on the east side of the Urals and went east down the Uy River to Ust-Uisk on the Tobol River where it connected to the ill-defined 'Siberian Line' along the forest-steppe boundary.

- In 1740 a report was made of Bashkir losses which gave: Killed: 16,893, Sent to Baltic regiments and fleet: 3,236, Women and children distributed (presumably as serfs): 8,382, Grand Total: 28,511. Fines: Horses: 12,283, Cattle and Sheep: 6,076, Money: 9,828 rubles. Villages destroyed: 696. As this was compiled from army reports it excludes losses from irregular raiding, hunger, disease and cold. All this was from an estimated Bashkir population of 100,000.

The Bashkirs lived between the Kama, Volga, Samara and Tobol Rivers. The Samara River extends from the hairpin curve of the Volga east to the base of the Urals. The Tobol is east of the Upper Ural River. Orsk is where the Ural turns westward. The Belaya River with the town of Ufa cuts through the center.

Demographics

The area settled by the Bashkirs in the Idel-Ural region according to the national census of 2010.

Further information: Bashkir language and Bashkortostan

The ethnic Bashkir population is estimated at roughly 2 million people (2009 SIL Ethnologue), of which about 1.4 million speak the Bashkir language, a Turkic language of the Kypchak group. The Russian census of 2002 recorded 1.38 million Bashkir speakers in the Russian Federation. Most Bashkirs are bilingual in Bashkir and Russian.The 2010 Russian census recorded 1,172,287 ethnic Bashkirs in Bashkortostan (29.5% of total population).

About 50% of Bashkirs are Muslim, 25% are unaffiliated, 11% are atheist, and 2% are pagan. There are also about less than 1% Protestant and Catholic Bashkirs.[8][9]

Culture

The Bashkirs traditionally practiced agriculture, cattle-rearing and bee-keeping. The half-nomadic Bashkirs wandered either the mountains or the steppes, herding cattle.Bashkir national dishes include a kind of gruel called öyrä and a cheese named qorot. Wild-hive beekeeping can be named as a separate component of the most ancient culture which is practiced in the same Burzyansky District near to the Shulgan-Tash cave.

«Ural-batyr» and «Akbuzat» are Bashkir national epics. Their plot concerns struggle of heroes against demonic forces. The peculiarity of them is that events and ceremonies described there can be addressed to a specific geographical and historical object –the Shulgan-Tash cave and its vicinities.

Religion

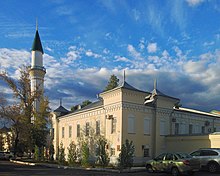

Caravanserai mosque in Orenburg, cultural monument of the Bashkir people, 1837—1844

Bashkirs began to convert to Islam from in the 9th century.[12] Arab traveler Ibn Fadlan in 921 met some of the Bashkirs, who were Muslims.[13] The final assertion of Islam among the Bashkirs occurred in the 1320s and 1330s (Golden Horde times). On the territory of Bashkortostan preserved the burial place of the first Imam of Historical Bashkortostan — The mausoleum of Hussein-Bek, 14th-century building. In 1788 Catherine the Great established the "Orenburg Mohammedan Spiritual Assembly" in Ufa, which was the first Muslim administrative center in Russia.

In yearly 1990s began the religious revival among the Bashkirs.[14] According to Talgat Tadzhuddin there are more than 1,000 mosques in Bashkortostan in 2010.[15]

The Bashkirs are predominantly Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi madhhab.[5]

Genetics

Regarding Y-DNA haplogroups, genetic studies have revealed that most Bashkir males belong to haplogroup R1b (R-M269 and R-M73) which is, on average, found at the frequency of 47,6 %. Following are the haplogroup R1a at the average frequency of 26.5%, and haplogroup N1c at 17%. In lower frequencies were also found haplogroups J2, C, O, E1b, G2a, L, N1b, I, T.[16]Most mtDNA haplogroups found in Bashkirs (65%) consist of the haplogroups G, D, С, Z and F; which are lineages characteristic of East Eurasian populations. On the other hand, mtDNA haplogroups characteristic of European and Middle Eastern populations were also found in significant amounts (35%).[17][18]

Theories of origin

The Bashkirs, photo by Mikhail Bukar, 1872.

- the "Kurgan hypothesis", i.e. that the original homeland of the Proto-Indo-Europeans lay immediately west of the Ural Mountains, in or near present-day Bashkortostan,[19] and;

Notable Bashkirs

- Alsou, singer (Bashkir father)

- Lyasan Utiasheva, gymnast and TV personality (Bashkir mother)

- Ildar Abdrazakov, opera singer

- Murtaza Rakhimov, first president of Bashkortostan

- Rustem Khamitov, president of Bashkortostan

- Zeki Velidi Togan, historian, Turkologist, and leader of the Bashkir revolutionary and liberation movement

- Salawat Yulayev, Bashkir national hero

- Irek Zaripov, biathlete and cross-country skier

- Tagir Kusimov, was a Soviet military leader.

- Zaynulla Rasulev, was a Bashkir religious leader in the 19th and early 20th centuries

- Kadir Timergazin, was also a Soviet petroleum geologist, the first doctor and professor of geological-mineralogical sciences from the Bashkirs, an honored scientist of the RSFSR.

- Mustai Karim, was a Bashkir Soviet poet, writer and playwright. He was named People's poet of the Bashkir Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (1963), Hero of Socialist Labour (1979), and winner of the Lenin Prize (1984) and the State Prize of the USSR (1972).

- Shaikhzada Babich, was a Bashkir poet, writer and playwright. Member of the Bashkir national liberation movement, one of the members of the Bashkir government (1917–1919).

- Kharrasov Mukhamet – was a rector of the Bashkir State University (2000–2010), Ph.D in physics, Honorary worker of Higher professional Education of Russia (2002).

- Yaroslava Shvedova - Kazakhstani tennis player (Bashkir mother)

References

- See, for example: Will Chang, Chundra Cathcart, David Hall, & Andrew Garrett, 'Ancestry-constrained phylogenetic analysis supports the Indo-European steppe hypothesis', Language, vol. 91, no. 1 (March) 2015, p. 196.

Sources

- Frhn, "De Baskiris", in Mrn. de l'Acad. de St-Pitersbourg, 1822.

- J. P. Carpini, "Liber Tartarorum", edited under the title "Relations des Mongols ou Tartares", by d'Avezac (Paris, 1838).

- Semenoff, "Geographical-statistic Dictionary of Russian Empire", 1863.

- Florinsky, in "Vestnik Evropy" magazine, 1874.

- Katarinskij, "Dictionnaire Bashkir-Russe", 1900.

- Gulielmus de Rubruquis, "The Journey of William of Rubruck to the Eastern Parts of the World", translated by V.W. Rockhill (London, 1900).

- William of Rubruck's "Account of the Mongols", 1900.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bashkirs". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bashkirs". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.- Alton S. Donnelly, "The Russian Conquest of Bashkiria 1552–1740": Yale Univ. Press, 1968.

- Summerfield, Stephen Cossack Hurrah: Russian Irregular Cavalry Organisation and Uniforms during the Napoleonic Wars, Partizan Press, 2005 ISBN 1-85818-513-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bashkirs. |

- Bashkirs at congress of Hungarians on YouTube

- Bashkir folk dance "Kahim Tura" on YouTube

- Culture of Bashkirs

- Bashkir folk-tales and legends

- The Bashkir nation: history pages (Russian)

- Photos of Bashkirs and their life in funds of the Library of Congress

- Photos of Bashkirs and their life in funds of the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (the Kunstkamera)

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

begin: Khazars.

"Khazar" and "Kazar" redirect here. For other uses, see Khazar (disambiguation).

|

|

It has been suggested that this article be split into a new article titled Khazar Khaganate. (Discuss.) (September 2015) |

| Kingdom of Khazaria Eastern Tourkia Hazar Kağanlığı |

|||||

| Khazar Khaganate | |||||

|

|||||

|

Khazar Khaganate, 650–850

|

|||||

| Capital | Balanjar (650-720 ca.) Samandar (720s-750) Atil (750-ca.965-969) |

||||

| Languages | Turkic Khazar | ||||

| Religion | Tengriism, Buddhism Judaism,[1] Christianity, Islam, Paganism, Religious syncretism[2] |

||||

| Political structure | Khazar Khaganate | ||||

| Khagan | |||||

| • | 618–628 | Tong Yabghu | |||

| • | 9th century | Bulan | |||

| • | 9th century | Obadiah | |||

| • | 9th century | Zachariah | |||

| • | 9th century | Manasseh | |||

| • | 9th century | Benjamin | |||

| • | 10th century | Aaron | |||

| • | 10th century | Joseph | |||

| • | 10th century | David | |||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||

| • | Established | 650? | |||

| • | Disestablished | 1048? | |||

| Population | |||||

| • | 7th century[3] est. | 1,400,000 | |||

| Currency | Yarmaq | ||||

|

History of the Turkic peoples Pre-14th century |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turkic Khaganate 552–744 | |||||||

| Western Turkic | |||||||

| Eastern Turkic | |||||||

| Avar Khaganate 564–804 | |||||||

| Khazar Khaganate 618–1048 | |||||||

| Xueyantuo 628–646 | |||||||

| Great Bulgaria 632–668 | |||||||

| Danube Bulgaria | |||||||

| Volga Bulgaria | |||||||

| Kangar union 659–750 | |||||||

| Turgesh Khaganate 699–766 | |||||||

| Uyghur Khaganate 744–840 | |||||||

| Karluk Yabgu State 756–940 | |||||||

| Kara-Khanid Khanate 840–1212 | |||||||

| Western Kara-Khanid | |||||||

| Eastern Kara-Khanid | |||||||

| Gansu Uyghur Kingdom 848–1036 | |||||||

| Kingdom of Qocho 856–1335 | |||||||

| Pecheneg Khanates 860–1091 |

Kimek Khanate 743–1035 |

||||||

| Cumania 1067–1239 |

Oghuz Yabgu State 750–1055 |

||||||

| Ghaznavid Empire 963–1186 | |||||||

| Seljuk Empire 1037–1194 | |||||||

| Seljuk Sultanate of Rum | |||||||

| Khwarazmian Empire 1077–1231 | |||||||

| Delhi Sultanate 1206–1526 | |||||||

| Mamluk dynasty | |||||||

| Khilji dynasty | |||||||

| Tughlaq dynasty | |||||||

| Golden Horde | [4][5][6] 1240s–1502 | |||||||

| Mamluk Sultanate (Cairo) 1250–1517 | |||||||

| Bahri dynasty | |||||||

| Ottoman Empire 1299-1923 | |||||||

|

Part of a series on the

|

|---|

| History of Tatarstan |

|

|

Part of a series on the

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Russia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Russia portal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Part of a series on the

|

|---|

| History of Ukraine |

|

| Ukraine portal |

Khazaria long served as a buffer state between the Byzantine empire and both the nomads of the northern steppes and the Umayyad empire, after serving as Byzantium's proxy against the Sasanian Persian empire. The alliance was dropped around 900. Byzantium began to encourage the Alans to attack Khazaria and weaken its hold on Crimea and the Caucasus, while seeking to obtain an entente with the rising Rus' power to the north, which it aspired to convert to Christianity.[17] Between 965 and 969, the Kievan Rus ruler Sviatoslav I of Kiev conquered the capital Atil and destroyed the Khazar state.

Originally, the Khazars were pagan Tengrist worshippers. The populace of the Khazar Khaganate appears to have been multi-confessional—a mosaic of pagan, Tengrist, Jewish, Christian and Muslim worshippers.[18] Beginning in the 8th century, Khazar royalty and notable segments of the aristocracy might have converted to Judaism. Khazar origins for, or suggestions Khazars were absorbed by many peoples, have been made regarding the Slavic Judaising Subbotniks, the Bukharan Jews, the Muslim Kumyks, Kazakhs, the Cossacks of the Don region, the Turkic-speaking Krymchaks and their Crimean neighbours the Karaites to the Moldavian Csángós, the Mountain Jews and others.[19][20][21] A modern theory, that the core of Ashkenazi Jewry emerged from a hypothetical Khazarian Jewish diaspora, is now viewed with scepticism by most scholars,[22] but occasionally supported by others.[23] The theory is sometimes associated with antisemitism[24] and anti-Zionism.[25]

Contents

- 1 Etymology

- 2 Linguistics

- 3 History

- 4 Religion

- 5 Claims of Khazar ancestry

- 6 In literature

- 7 Cities associated with the Khazars

- 8 See also

- 9 Notes

- 10 References

- 11 External links

Etymology

Gyula Németh, following Zoltán Gombocz, derived Xazar from a hypothetical *Qasar reflecting a Turkic root qaz- ("to ramble, to roam") being an hypothetical velar variant of Common Turkic kez-.[26] With the publication of the fragmentary Tes and Terkhin inscriptions of the Uyğur empire (744-840) where the form 'Qasar' is attested, though uncertainty remains whether this represents a personal or tribal name, gradually other hypotheses emerged. Louis Bazin derived it from Turkic qas- ("tyrannize, oppress, terrorize") on the basis of its phonetic similarity to the Uyğur tribal name, Qasar.[27] András Róna-Tas connects it with Kesar, the Pahlavi transcription of the Roman title Caesar.[28]D.M.Dunlop tried to link the Chinese term for "Khazars" to one of the tribal names of the Uyğur Toquz Oğuz, namely the Gésà.[29][30] The objections are that Uyğur Gesa/Qasar was not a tribal name but rather the surname of the chief of the Sikari tribe of the Toquz Oğuz, and that in Middle Chinese the ethnonym "Khazars", always prefaced with the word Tūjué signifying 'Türk' (Tūjué Kěsà bù:突厥可薩部; Tūjué Hésà:突厥曷薩), is transcribed with characters different from those used to render the Qa- in the Uyğur word 'Qasar'.[31][32][33]

After their conversion it is reported that they adopted the Hebrew script,[34] and it is likely that, though speaking a Türkic language, the Khazar chancellery under Judaism probably corresponded in Hebrew.[35] In Expositio in Matthaeum Evangelistam, Gazari, presumably Khazars, are referred to as the Hunnic people living in the lands of Gog and Magog and said to be circumcised and omnem Judaismum observat observing all the laws of Judaism.

Linguistics

Main article: Khazar language

Determining the origins and nature of the Khazars is closely bound with theories of their languages,

but it is a matter of intricate difficulty since no indigenous records

in the Khazar language survive, and the state itself was polyglot and polyethnic.[36] Whereas the royal or ruling elite probably spoke an eastern variety of Shaz Turkic, the subject tribes appear to have spoken varieties of Lir Turkic, such as Oğuric, a language variously identified with Bulğaric, Chuvash, and Hungarian (the latter based upon the assertion of the Persian historian al-Iṣṭakhrī that the Khazar language was different from any other known tongue).[37][38] One method for tracing their origins consists in analysis of the possible etymologies behind the ethnonym Khazar itself.History

Tribal origins and early history

The tribes[39] that were to comprise the Khazar empire were not an ethnic union, but a congeries of steppe nomads and peoples who came to be subordinated, and subscribed to a core Tűrkic leadership.[40] Many Tűrkic groups, such as the Oğuric peoples, including Šarağurs, Oğurs, Onoğurs, and Bulğars who earlier formed part of the Tiĕlè (鐵勒) confederation, are attested quite early, having been driven West by the Sabirs, who in turn fled the Asian Avars, and began to flow into the Volga-Caspian-Pontic zone from as early as the 4th century CE and are recorded by Priscus to reside in the Western Eurasian steppelands as early as 463.[41][42] They appear to stem from Mongolia and South Siberia in the aftermath of the fall of the Hunnic/Xiōngnú nomadic polities. A variegated tribal federation led by these Tűrks, probably comprising a complex assortment of Iranian,[43] proto-Mongolic, Uralic, and Palaeo-Siberian clans, vanquished the Rouran Khaganate of the hegemonic central Asian Avars in 552 and swept westwards, taking in their train other steppe nomads and peoples from Sogdiana.[44]The ruling family of this confederation may have hailed from the Āshǐnà (阿史那) clan of the West Türkic tribes,[45] though Constantine Zuckerman regards Āshǐnà and their pivotal role in the formation of the Khazars with scepticism.[46] Golden notes that Chinese and Arabic reports are almost identical, making the connection a strong one, and conjectures that their leader may have been Yǐpíshèkuì (Chinese:乙毗射匱), who lost power or was killed around 651.[47] Moving west, the confederation reached the land of the Akatziroi,[48] who had been important allies of Byzantium in fighting off Attila's army.

Rise of the Khazar state

An embryonic state of Khazaria began to form sometime after 630,[49] when it emerged from the breakdown of the larger Göktürk Qağanate. Göktürk armies had penetrated the Volga by 549, ejecting the Avars, who were then forced to flee to the sanctuary of the Hungarian plain. The Āshǐnà clan whose tribal name was 'Türk' (the strong one) appear on the scene by 552, when they overthrew the Rourans and established the Göktürk Qağanate.[50] By 568, these Göktürks were probing for an alliance with Byzantium to attack Persia. An internecine war broke out between the senior eastern Göktürks and the junior West Turkic Qağanate some decades later, when on the death of Taspar Qağan, a succession dispute led to a dynastic crisis between Taspar's chosen heir, the Apa Qağan, and the ruler appointed by the tribal high council, Āshǐnà Shètú (阿史那摄图), the Ishbara Qağan.By the first decades of the 7th century, the Āshǐnà yabgu Tong managed to stabilize the Western division, but upon his death, after providing crucial military assistance to Byzantium in routing the Sasanian army in the Persian heartland,[51][52] the Western Turkic Qağanate dissolved under pressure from the encroaching Tang dynasty armies and split into two competing federations, each consisting of five tribes, collectively known as the "Ten Arrows" (On Oq). Both briefly challenged Tang hegemony in eastern Turkestan. To the West, two new nomadic states arose in the meantime, Old Great Bulgaria under Kubrat, the Duōlù clan leader, and the Nǔshībì subconfederation, also consisting of five tribes.[53] The Duōlù challenged the Avars in the Kuban River-Sea of Azov area while the Khazar Qağanate consolidated further westwards, led apparently by an Āshǐnà dynasty. With a resounding victory over the tribes in 657, engineered by General Sū Dìngfāng (蘇定方), Chinese overlordship was imposed to their East after a final mop-up operation in 659, but the two confederations of Bulğars and Khazars fought for supremacy on the western steppeland, and with the ascendency of the latter, the former either succumbed to Khazar rule or, as under Asparukh, Kubrat's son, shifted even further west across the Danube to lay the foundations of the Bulğar state in the Balkans (c. 679).[54][55]

The Qağanate of the Khazars thus took shape out of the ruins of this nomadic empire as it broke up under pressure from the Tang dynasty armies to the east sometime between 630-650.[47] After their conquest of the lower Volga region to the East and an area westwards between the Danube and the Dniepr, and their subjugation of the Onoğur-Bulğar union, sometime around 670, a properly constituted Khazar Qağanate emerges,[56] becoming the westernmost successor state of the formidable Göktürk Qağanate after its disintegration. According to Omeljan Pritsak, the language of the Onoğur-Bulğar federation was to become the lingua franca of Khazaria[57] as it developed into what Lev Gumilev called a 'steppe Atlantis' (stepnaja Atlantida/ Степная Атлантида).[58] The high status soon to be accorded this empire to the north is attested by Ibn al-Balḫî's Fârsnâma (c. 1100), which relates that the Sasanian Shah, Ḫusraw 1, Anûsîrvân, placed three thrones by his own, one for the King of China, a second for the King of Byzantium, and a third for the king of the Khazars. Though anachronistic in retrodating the Khazars to this period, the legend, in placing the Khazar qağan on a throne with equal status to kings of the other two superpowers, bears witness to the reputation won by the Khazars from early times.[59][60]

Khazar state: culture and institutions

Royal Diarchy with sacral Qağanate

Khazaria developed [61] a Dual kingship governance structure, typical among Turkic nomads, consisting of a shad/bäk and a qağan,.[62] The emergence of this system may be deeply entwined with the conversion to Judaism.[63] According to Arabic sources, the lesser king was called îšâ and the greater king Khazar xâqân; the former managed commanded the military, while the greater king's role was primarily sacral, less concerned with daily affairs. The greater king was recruited from the Khazar house of notables (ahl bait ma'rûfīn) and, in an initiation ritual, was nearly strangled until he declared the number of years he wished to reign, on the expiration of which he would be killed by the nobles.[64][65][66][67] The deputy ruler would enter the presence of the reclusive greater king only with great ceremony, approaching him barefoot to prostrate himself in the dust and then light a piece of wood as a purifying fire, while waiting humbly and calmly to be summoned.[68] Particularly elaborate rituals accompanied a royal burial. At one period, travellers had to dismount, bow before the ruler's tomb, and then walk away on foot.[69] Subsequently, the charismatic sovereign's burial place was hidden from view, with a palatial structure ('Paradise') constructed and then hidden under rerouted river water to avoid disturbance by evil spirits and later generations. Such a royal burial ground (qoruq) is typical of inner Asian peoples.[70] Both the îšâ and the xâqân converted to Judaism sometime in the 8th century, while the rest, according to the Persian traveller Ahmad ibn Rustah, probably followed the old Tūrkic religion.[71][72]Ruling elite

Warrior with his captive from the Treasure of Nagyszentmiklós. Experts cannot agree if this warrior represents a Khazar, Pannonian Avar, or Bulgar.

Settlements were governed by administrative officials known as tuduns. In some cases, such as the Byzantine settlements in southern Crimea, a tudun would be appointed for a town nominally within another polity's sphere of influence. Other officials in the Khazar government included dignitaries referred to by ibn Fadlan as Jawyshyghr and Kündür, but their responsibilities are unknown.

Demographics

It has been estimated that from 25 to 28 distinct ethnic groups made up the population of the Khazar Qağanate, aside from the ethnic elite. The ruling elite seems to have been constituted out of nine tribes/clans, themselves ethnically heterogeneous, spread over perhaps nine provinces or principalities, each of which would have been allocated to a clan.[65] In terms of caste or class, some evidence suggests that there was a distinction, whether racial or social is unclear, between "White Khazars" (ak-Khazars) and "Black Khazars" (qara-Khazars).[65] The 10th-century Muslim geographer al-Iṣṭakhrī claimed that the White Khazars were strikingly handsome with reddish hair, white skin, and blue eyes, while the Black Khazars were swarthy, verging on deep black, as if they were "some kind of Indian".[81] Many Turkic nations had a similar (political, not racial) division between a "white" ruling warrior caste and a "black" class of commoners; the consensus among mainstream scholars is that Istakhri was confused by the names given to the two groups.[82] However, Khazars are generally described by early Arab sources as having a white complexion, blue eyes, and reddish hair.[83][84] The name of the presumed founding Āshǐnà clan itself may reflect an etymology suggestive of a darkish colour.[85][86] The distinction appears to have survived the collapse of the Khazarian empire. Later Russian chronicles, commenting on the role of the Khazars in the magyarization of Hungary, refer to them as "White Oghurs" and Magyars as "Black Ogurs".[87] Studies of the physical remains, such as skulls at Sarkel, have revealed a mixture of Slavic, other European, and a few Mongolian types.[88]Economy

The import and export of foreign wares, and the revenues derived from taxing their transit, was a key hallmark of the Khazar economy, though it is said also to have produced isinglass.[89] Distinctively among the nomadic steppe polities, the Khazar Qağanate developed a self-sufficient domestic Saltovo[90] economy, a combination of traditional pastoralism - allowing sheep and cattle to be exported - extensive agriculture, abundant use of the Volga's rich fishing stocks, together with craft manufacture, with a diversification in lucrative returns from taxing international trade given its pivotal control of major trade routes. The Khazars constituted one of the two great furnishers of slaves to the Muslim market (the other being the Iranian Sâmânid amîrs), supplying it with captured Slavs and tribesmen from the Eurasian northlands.[91] It was profits from the latter which enabled it to maintain a standard army of Khwarezm Muslim troops. The capital Atil reflected the division: Kharazān on the western bank where the king and his Khazar elite, with a retinue of some 4,000 attendants, dwelt, and Itil proper to the East, inhabited by Jews, Christians, Muslims and slaves and by craftsmen and foreign merchants.[92] The ruling elite wintered in the city and spent from spring to late autumns in their fields. A large irrigated greenbelt, drawing on channels from the Volga river, lay outside the capital, where meadows and vineyards extended for some 20 farsakhs (ca. 60 miles?).[93] While customs duties were imposed on traders, and tribute and tithes were exacted from 25-30 tribes, with a levy of one sable skin, squirrel pelt, sword, dirham per hearth or ploughshare, or hides, wax, honey and livestock, depending on the zone. Trade disputes were handled by a commercial tribunal in Atil consisting of 7 judges, two for each of the monotheistic inhabitants (Jews, Muslims, Christians) and one for the pagans.[94]Khazars and Byzantium

See also: Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 and Third Perso-Turkic War

Byzantine diplomatic policy towards the steppe peoples generally consisted of encouraging them to fight among themselves. The Pechenegs provided great assistance to the Byzantines in the 9th century in exchange for regular payments.[95] Byzantium also sought alliances with the Göktürks against common enemies: in the early 7th century, one such alliance was brokered with the Western Tűrks against the Persian Sasanians in the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628. The Byzantines called Khazaria Tourkía, and by the 9th. century refers to the Khazars as 'Turks'.[96] During the period leading up to and after the siege of Constantinople in 626, Heraclius sought help via emissaries, and eventually personally, from a Göktürk chieftain[97] of the Western Tűrkic Qağanate, Tong Yabghu Qağan, in Tiflis, plying him with gifts and the promise of marriage to his daughter, Epiphania.[98] Tong Yabghu responded by sending a large force to ravage the Persian empire, marking the start of the Third Perso-Turkic War.[99] A joint Byzantine-Tűrk operation breached the Caspian gates and sacked Derbent in 627. Together they then besieged Tiflis, where the Byzantines used traction trebuchets (ἑλέπόλεις) to breach the walls, one of their first known uses by the Byzantines.[citation needed]

After the campaign, Tong Yabghu is reported, perhaps with some

exaggeration, to have left some 40,000 troops behind with Heraclius.[100]

Though occasionally identified with Khazars, the Göktürk identification

is more probable since the Khazars only emerged from that group after

the fragmentation of the former sometime after 630.[49] Sasanian Persia never recovered from the devastating defeat wrought by this invasion.[101]

Khazar Khaganate and surrounding states, c. 820 (area of direct Khazar control in dark blue, sphere of influence in purple).

Decades later, Leo III (ruled 717-741) made a similar alliance to coordinate strategy against a common enemy, the Muslim Arabs. He sent an embassy to the Khazar qağan Bihar and married his son, the future Constantine V (ruled 741-775), to Bihar's daughter, a princess referred to as Tzitzak, in 732. On converting to Christianity, she took the name Irene. Constantine and Irene had a son, the future Leo IV (775-780), who thereafter bore the sobriquet, "the Khazar".[105][106] Leo died in mysterious circumstances after his Athenian wife bore him a son, Constantine VI, who on his majority co-ruled with his mother, the dowager. He proved unpopular, and his death ended the dynastic link of the Khazars to the Byzantine throne.[citation needed] By the 8th century, Khazars dominated the Crimea (650-c.950), and even extended their influence into the Byzantine peninsula of Cherson until it was wrested back in the 10th century.[107] Khazar and Farghânian (Φάργανοι) mercenaries constituted part of the imperial Byzantine Hetaireia bodyguard after its formation in 840, a position that could openly be purchased by a payment of 7 pounds of gold.[108][109]

Arab–Khazar wars

Main article: Arab–Khazar Wars

During the 7th and 8th centuries, the Khazars fought a series of wars against the Umayyad Caliphate and its Abbasid successor. The First Arab-Khazar War began during the first phase of Muslim expansion. By 640, Muslim forces had reached Armenia; in 642 they launched their first raid across the Caucasus under Abd ar-Rahman ibn Rabiah. In 652 Arab forces advanced on the Khazar capital, Balanjar, but were defeated, suffering heavy losses; according to Persian historians such as al-Tabari, both sides in the battle used catapults against the opposing troops. A number of Russian sources give the name of a Khazar khagan from this period as Irbis

and describe him as a scion of the Göktürk royal house, the Ashina.

Whether Irbis ever existed is open to debate, as is whether he can be

identified with one of the many Göktürk rulers of the same name.Due to the outbreak of the First Muslim Civil War and other priorities, the Arabs refrained from repeating an attack on the Khazars until the early 8th century.[110] The Khazars launched a few raids into Transcaucasian principalities under Muslim dominion, including a large-scale raid in 683–685 during the Second Muslim Civil War that rendered much booty and many prisoners.[111] There is evidence from the account of al-Tabari that the Khazars formed a united front with the remnants of the Göktürks in Transoxiana.

Caucasus region, c. 750

In 724, Arab general al-Jarrah ibn Abdallah al-Hakami inflicted a crushing defeat on the Khazars in a long battle between the rivers Cyrus and Araxes, then moved on to capture Tiflis, bringing Caucasian Iberia under Muslim suzerainty. The Khazars struck back in 726, led by a prince named Barjik, launching a major invasion of Albania and Azerbaijan; by 729, the Arabs had lost control of northeastern Transcaucasia and were thrust again into the defensive. In 730, Barjik invaded Iranian Azerbaijan and defeated Arab forces at Ardabil, killing the general al-Djarrah al-Hakami and briefly occupying the town. Barjik was defeated and killed the next year at Mosul, where he directed Khazar forces from a throne mounted with al-Djarrah's severed head. Arab armies led first by the prince Maslamah ibn Abd al-Malik and then by Marwan ibn Muhammad (later Caliph Marwan II) poured across the Caucasus and in 737 defeated a Khazar army led by Hazer Tarkhan, briefly occupying Atil itself. The Qağan was forced to accept terms involving conversion to Islam, and to subject himself to the Caliphate, but the accommodation was short-lived as a combination of internal instability among the Umayyads and Byzantine support undid the agreement within three years, and the Khazars re-asserted their independence.[113] The adoption of Judaism by the Khazars, which in this theory would have taken place around 740, may have been part of this re-assertion of independence.

Whatever the impact of Marwan's campaigns, warfare between the Khazars and the Arabs ceased for more than two decades after 737. Arab raids continued until 741, but their control in the region was limited as maintaining a large garrison at Derbent further depleted the already overstretched army. A third Muslim civil war soon broke out, leading to the Abbasid Revolution and the fall of the Umayyad dynasty in 750.

In 758, the Abbasid Caliph al-Mansur attempted to strengthen diplomatic ties with the Khazars, ordering Yazid ibn Usayd al-Sulami, one of his nobles and the military governor of Armenia, to take a royal Khazar bride. Yazid married a daughter of Khazar Khagan Baghatur, but she died inexplicably, possibly in childbirth. Her attendants returned home, convinced that some Arab faction had poisoned her, and her father was enraged. Khazar general Ras Tarkhan invaded south of the Caucasus in 762–764, devastating Albania, Armenia, and Iberia, and capturing Tiflis. Thereafter relations became increasingly cordial between the Khazars and the Abbasids, whose foreign policies were generally less expansionist than the Umayyads, broken only by a series of raids in 799 over another failed marriage alliance.

Rise of the Rus' and the collapse of the Khazarian state

Trade routes of the Black Sea region, 8th-11th centuries

Site of the Khazar fortress at Sarkel (aerial photo from excavations conducted by Mikhail Artamonov in the 1950s).

By the 880s, Khazar control of the Middle Dnieper from Kiev, where they collected tribute from Eastern Slavic tribes, began to wane as Oleg of Novgorod wrested control of the city from the Varangian warlords Askold and Dir, and embarked on what was to prove to be the foundation of a Rus' empire.[127] The Khazars had initially allowed the Rus' to use the trade route along the Volga River, and raid southwards. According to al-Masudi, the qağan is said to have given his assent on the condition that the Rus' give him half of the booty.[124] In 913, however, two years after Byzantium concluded a peace treaty with the Rus' (911). A Varangian foray, with Khazar connivance, through Arab lands led to a request to the Khazar throne by the Khwârazmian Islamic guard for permission to retaliate against the large Rus' contingent on its return. The purpose was to revenge the violence the Rus' razzia had inflicted on their fellow Muslim believers.[128] The Rus' force was thoroughly routed and massacred.[124] The Khazar rulers closed the passage down the Volga to the Rus', sparking a war. In the early 960s, Khazar ruler Joseph wrote to Hasdai ibn Shaprut about the deterioration of Khazar relations with the Rus': 'I protect the mouth of the river (Itil-Volga) and prevent the Rus arriving in their ships from setting off by sea against the Ishmaelites and (equally) all (their) enemies from setting off by land to Bab. '[129]

Sviatoslav I of Kiev (in boat), destroyer of the Khazar Khaganate.[130]

In the Russian chronicle the vanquishing of the Khazar traditions is associated with Vladimir's conversion in 986.[133] According to the Primary Chronicle, in 986 Khazar Jews were present at Vladimir's disputation to decide on the prospective religion of the Kievian Rus'.[citation needed] Whether these were Jews who had settled in Kiev or emissaries from some Jewish Khazar remnant state is unclear. Conversion to one of the faiths of the people of Scripture was a precondition to any peace treaty with the Arabs, whose Bulgar envoys had arrived in Kiev after 985.[134]

A visitor to Atil wrote soon after the sacking of the city that its vineyards and garden had been razed, that not a grape or raisin remained in the land, and not even alms for the poor were available.[135] An attempt to rebuild may have been undertaken, since Ibn Hawqal and al-Muqaddasi refer to it after that date, but by Al-Biruni's time (1048) it was in ruins.[136]

Aftermath: impact, decline and dispersion

Though Poliak argued that the Khazar kingdom did not wholly succumb to Sviatoslav's campaign, but lingered on until 1224, when the Mongols invaded Rus',[137][138] by most accounts, the Rus'-Oghuz campaigns left Khazaria devastated, with perhaps many Khazarian Jews in flight,[139] and leaving behind at best a minor rump state. It left little trace, except for some placenames,[140] and much of its population was undoubtedly absorbed in successor hordes.[141] Al-Muqaddasi, writing ca.985, mentions Khazar beyond the Caspian sea as a district of 'woe and squalor', with honey, many sheep and Jews.[142] Kedrenos mentions a joint Rus'-Byzantine attack on Khazaria in 1016, which defeated its ruler Georgius Tzul. The name suggests Christian affiliations. The account concludes by saying, that after Tzul's defeat, the Khazar ruler of "upper Media", Senaccherib, had to sue for peace and submission.[143] In 1024 Mstislav of Chernigov (one of Vladimir's sons) marched against his brother Yaroslav with an army that included "Khazars and Kassogians" in a repulsed attempt to restore a kind of 'Khazarian'-type dominion over Kiev.[132]Ibn al-Athir's mention of a 'raid of Faḍlūn the Kurd against the Khazars' in 1030 CE, in which 10,000 of his men were vanquished by the latter, has been taken (by ) as a reference to such a Khazar remnant, but Barthold identified this Faḍlūn as Faḍl ibn Muḥammad and the 'Khazars' as either Georgians or Abkhazians.[144][145] A Kievian prince named Oleg, grandson of Jaroslav was reportedly kidnapped by "Khazars" in 1079 and shipped off to Constantinople, although most scholars believe that this is a reference to the Cumans-Kipchaks or other steppe peoples then dominant in the Pontic region. Upon his conquest of Tmutarakan in the 1080s Oleg Sviatoslavich, son of a prince of Chernigov, gave himself the title "Archon of Khazaria".[132] In 1083 Oleg is said to have exacted revenge on the Khazars after his brother Roman was killed by their allies, the Polovtsi/Cumans. After one more conflict with these Polovtsi in 1106, the Khazars fade from history.[143]By the end of the 12th century, Petachiah of Ratisbon reported traveling through what he called "Khazaria", and had little to remark on other than describing its minim (sectaries) living amidst desolation in perpetual mourning.[146] The reference seems to be to Karaites.[147] The Franciscan missionary William of Rubruck likewise found only impoverished pastures in the lower Volga area where Ital once lay.[93] Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, the papal legate to the court of the Mongol Khan Guyuk at that time, mentioned an otherwise unattested Jewish tribe, the Brutakhi, perhaps in the Volga region. Though connections are made to the Khazars, the link is based merely on a common attribution of Judaism.[148]

The Pontic steppes, c. 1015 (areas in blue possibly still under Khazar control).