Nalanda

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Nalanda

| नालंदा |

The ruins of Nalanda Mahavihara

|

|

|

| Location |

Nalanda district, Bihar, India |

| Coordinates |

25°08′12″N 85°26′38″ECoordinates: 25°08′12″N 85°26′38″ECoordinates:  25°08′12″N 85°26′38″E 25°08′12″N 85°26′38″E |

| Type |

Centre of learning |

| Length |

800 ft (240 m) |

| Width |

1,600 ft (490 m) |

| Area |

12 ha (30 acres) |

| History |

| Founded |

5th century CE |

| Abandoned |

13th century CE |

| Events |

Likely ransacked by Bakhtiyar Khilji in c. 1200 CE |

| Site notes |

| Excavation dates |

1915–1937, 1974–1982[1] |

| Archaeologists |

David B. Spooner, Hiranand Sastri, J.A. Page, M. Kuraishi, G.C. Chandra, N. Nazim, Amalananda Ghosh[2]:59 |

| Public access |

Yes |

| Website |

Nalanda (ASI) |

|

Nalanda (

Hindi:

नालंदा;

IAST:

Nālandā;

/naːlən̪d̪aː/) was an acclaimed

Mahavihara, a large

Buddhist monastery in the ancient kingdom of

Magadha (modern-day

Bihar) in

India. The site is located about 95 kilometres southeast of

Patna near the town of

Bihar Sharif, and was a centre of learning from the fifth century CE to

c. 1200 CE.

[4]:149

The highly formalized methods of

Vedic learning helped inspire the establishment of large teaching institutions such as

Taxila, Nalanda, and Vikramashila

[5] which are often characterised as India's early universities.

[4]:148[6]:174[7][8]:43[9]:119 Nalanda flourished under the patronage of the

Gupta Empire in the 5th and 6th centuries and later under

Harsha, the emperor of

Kannauj.

[10]:329

The liberal cultural traditions inherited from the Gupta age resulted

in a period of growth and prosperity until the ninth century. The

subsequent centuries were a time of gradual decline, a period during

which the

tantric developments of Buddhism became most pronounced in eastern India under the

Pala Empire.

[10]:344

At its peak, the school attracted scholars and students from near and far with some travelling all the way from

Tibet,

China,

Korea, and

Central Asia.

[6]:169

Archaeological evidence also notes contact with the Shailendra dynasty

of Indonesia, one of whose kings built a monastery in the complex.

Much of our knowledge of Nalanda comes from the writings of pilgrim monks from East Asia such as

Xuanzang and

Yijing who travelled to the Mahavihara in the 7th century.

Vincent Smith

remarked that "a detailed history of Nalanda would be a history of

Mahayanist Buddhism". Many of the names listed by Xuanzang in his

travelogue as products of Nalanda are the names of those who developed

the philosophy of Mahayana.

[10]:334 All students at Nalanda studied

Mahayana as well as the texts of the eighteen (

Hinayana) sects of Buddhism. Their curriculum also included other subjects such as the

Vedas, logic, Sanskrit grammar, medicine and

Samkhya.

[11][5][12][10]:332–333

Nalanda was very likely ransacked and destroyed by an army of the Muslim

Mamluk Dynasty under

Bakhtiyar Khilji in

c. 1200 CE.

[13]

While some sources note that the Mahavihara continued to function in a

makeshift fashion for a while longer, it was eventually abandoned and

forgotten until the 19th century when the site was surveyed and

preliminary excavations were conducted by the

Archaeological Survey of India.

Systematic excavations commenced in 1915 which unearthed eleven

monasteries and six brick temples neatly arranged on grounds 12 hectares

in area. A trove of sculptures, coins, seals, and inscriptions have

also been discovered in the ruins many of which are on display in the

Nalanda Archaeological Museum situated nearby. Nalanda is now a notable

tourist destination and a part of the Buddhist tourism circuit.

Etymology

A number of theories exist about the etymology of the name,

Nālandā. According to the

Tang Dynasty Chinese pilgrim,

Xuanzang, it comes from

Na alam dā meaning

no end in gifts or

charity without intermission.

Yijing, another Chinese traveller, however, derives it from

Nāga Nanda referring to the name (

Nanda) of a snake (

naga) in the local tank.

[14]:3 Hiranand Sastri, an archaeologist who headed the excavation of the ruins, attributes the name to the abundance of

nālas (lotus-stalks) in the area and believes that Nalanda would then represent

the giver of lotus-stalks.

[15]

Early history

A statue of Gautama Buddha at Nalanda in 1895.

Nalanda was initially a prosperous village by a major trade route that ran through the nearby city of

Rajagriha (modern

Rajgir) which was then the capital of

Magadha.

[16] It is said that the

Jain thirthankara,

Mahavira, spent 14 rainy seasons at Nalanda.

Gautama Buddha too is said to have delivered lectures in a nearby mango grove named

Pavarika and one of his two chief disciples,

Shariputra, was born in the area and later attained

nirvana there.

[4]:148[10]:328 This traditional association with Mahavira and Buddha tenuously dates the existence of the

village to at least the 5th–6th century BCE.

Not much is known of Nalanda in the centuries hence.

Taranatha, the 17th-century Tibetan Lama, states that the 3rd-century BCE

Mauryan and Buddhist emperor,

Ashoka, built a great temple at Nalanda at the site of Shariputra's

chaitya. He also places 3rd-century CE luminaries such as the

Mahayana philosopher,

Nagarjuna, and his disciple,

Aryadeva,

at Nalanda with the former also heading the institution. Taranatha also

mentions a contemporary of Nagarjuna named Suvishnu building 108

temples at the location. While this could imply that there was a

flourishing centre for Buddhism at Nalanda before the 3rd century, no

archaeological evidence has been unearthed to support the assertion.

When

Faxian, an early Chinese Buddhist pilgrim to India, visited

Nalo, the site of Shariputra's

parinirvana, at the turn of the 5th century CE, all he found worth mentioning was a

stupa.

[7]:37[14]:4

Nalanda in the Gupta era

Rear view of the ruins of the Baladitya Temple in 1872.

Nalanda's datable history begins under the

Gupta Empire[17] and a seal identifies a monarch named Shakraditya (

Śakrāditya) as its founder. Both

Xuanzang and a Korean pilgrim named Prajnyavarman (

Prajñāvarman) attribute the foundation of a

sangharama (monastery) at the site to him.

[7]:42 Shakraditya is identified with the 5th-century CE Gupta emperor,

Kumaragupta I (

r. c. 415 – c. 455 CE), whose coin has been discovered at Nalanda.

[6]:166[10]:329 His successors,

Buddhagupta, Tathagatagupta,

Baladitya, and Vajra, later extended and expanded the institution by building additional monasteries and temples.

[14]:5

The Guptas were traditionally a

Brahmanical dynasty.

Narasimhagupta (Baladitya) however, was brought up under the influence of the Mahayanist philosopher,

Vasubandhu.

He built a sangharama at Nalanda and also a 300 ft (91 m) high vihara

with a Buddha statue within which, according to Xuanzang, resembled the

"great Vihara built under the

Bodhi tree".

The Chinese monk also noted that Baladitya's son, Vajra, who

commissioned a sangharama as well, "possessed a heart firm in faith".

[7]:45[10]:330

The post-Gupta era

The post-Gupta period saw a long succession of kings who continued

building at Nalanda "using all the skill of the sculptor". At some

point, a "king of central India" built a high wall along with a gate

around the now numerous edifices in the complex. Another monarch

(possibly of the

Maukhari dynasty) named Purnavarman who is described as "the last of the race of

Ashoka-raja", erected an 80 ft (24 m) high copper image of Buddha to cover which he also constructed a pavilion of six stages.

[7]:55

However, after the decline of the Guptas, the most notable patron of the Mahavihara was

Harsha, the 7th-century emperor of

Kannauj.

Harsha was a converted Buddhist and considered himself a servant of the

monks of Nalanda. He built a monastery of brass within the Mahavihara

and remitted to it the revenues of 100 villages. He also directed 200

households in these villages to supply the institution's monks with

requisite amounts of rice, butter, and milk on a daily basis. Around a

thousand monks from Nalanda were present at Harsha's royal congregation

at Kannauj.

[4]:151[14]:5

Much of what is known of Nalanda prior to the 8th century is based on the travelogues of the Chinese monks,

Xuanzang (

Si-Yu-Ki) and

Yijing (

A Record of the Buddhist Religion As Practised in India and the Malay Archipelago).

Xuanzang in Nalanda

8th century

Dunhuang cave mural depicts Xuanzang returning from India.

Xuanzang (also known as Hiuen Tsang) travelled around India between the years of 630 and 643 CE,

[9]:110 and visited Nalanda first in 637 and then again in 642, spending a total of around two years at the monastery.

[18]:237 He was warmly welcomed in Nalanda where he received the Indian name of Mokshadeva

[14]:8 and studied under the guidance of

Shilabhadra, the venerable head of the institution at the time.

[7]:111

He believed that the aim of his arduous overland journey to India had

been achieved as in Shilabhadra he had at last found an incomparable

teacher to instruct him in

Yogachara,

a school of thought that had then only partially been transmitted to

China. Besides Buddhist studies, the monk also attended courses in

grammar, logic, and Sanskrit, and later also lectured at the Mahavihara.

[18]:124

In the detailed account of his stay at Nalanda, the pilgrim describes the view out of the window of his quarters thus,

[19]

Moreover, the whole establishment is surrounded by a brick wall,

which encloses the entire convent from without. One gate opens into the

great college, from which are separated eight other halls standing in

the middle (of the Sangharama). The richly adorned towers, and

the fairy-like turrets, like pointed hill-tops are congregated together.

The observatories seem to be lost in the vapours (of the morning), and the upper rooms tower above the clouds.

Xuanzang was a contemporary and an esteemed guest of Harsha and catalogued the emperor's munificence in some detail.

[7]:55 According to Xuanzang's biographer,

Hwui-Li, Nalanda was held in contempt by some

Sthaviras

for its emphasis on Mahayana philosophy. They reportedly chided King

Harsha for patronising Nalanda during one of his visits to

Odisha, mocking the "sky-flower"

[clarification needed] philosophy taught there and suggesting that he might as well patronise a

Kapalika temple.

[10]:334

When this occurred, Harsha notified the chancellor of Nalanda, who sent

the monks Sagaramati, Prajnyarashmi, Simharashmi, and Xuanzang to

refute the views of the monks from

Odisha.

[20]:171

Xuanzang returned to China with 657 Buddhist texts (many of them

Mahayanist) and 150 relics carried by 20 horses in 520 cases, and

translated 74 of the texts himself.

[9]:110[18]:177

In the thirty years following his return, no fewer than eleven

travellers from China and Korea are known to have visited famed Nalanda.

[14]:9

Yijing in Nalanda

A map of Nalanda and its environs from Alexander Cunningham's 1861–62 ASI report which shows a number of ponds (pokhar) around the Mahavihara.

Inspired by the journeys of

Faxian and Xuanzang, the pilgrim,

Yijing (also known as I-tsing), after studying

Sanskrit in

Srivijaya, arrived in India in 673 CE. He stayed there for fourteen years, ten of which he spent at the Nalanda Mahavihara.

[4]:144 When he returned to China in 695, he had with him 400 Sanskrit texts which were subsequently translated.

[21]

Unlike his predecessor, Xuanzang, who also describes the geography

and culture of 7th-century India, Yijing's account primarily

concentrates on the practice of Buddhism in the land of its origin and

detailed descriptions of the customs, rules, and regulations of the

monks at the monastery. In his chronicle, Yijing notes that revenues

from 200 villages (as opposed to 100 in Xuanzang's time) had been

assigned toward the maintenance of Nalanda.

[4]:151 He described there being eight halls with as many as 300 apartments.

[6]:167

According to him, daily life at Nalanda included a series of rites that

were followed by all. Each morning, a bell was rung signalling the

bathing hour which led to hundreds or thousands of monks proceeding from

their viharas towards a number of great pools of water in and around

the campus where all of them took their bath. This was followed by

another gong which signalled the ritual ablution of the image of the

Buddha. The

chaityavandana was conducted in the evenings which included a "three-part service", the chanting of a prescribed set of hymns,

shlokas,

and selections from scriptures. While it was usually performed at a

central location, Yijing states that the sheer number of residents at

Nalanda made large daily assemblies difficult. This resulted in an

adapted ritual which involved a priest, accompanied by lay servants and

children carrying incense and flowers, travelling from one hall to the

next chanting the service. The ritual was completed by twilight.

[10]:128–130

Nalanda in the Pala era

The

Palas

established themselves in North-eastern India in the 8th century and

reigned until the 12th century. Although they were a Buddhist dynasty,

Buddhism in their time was a mixture of the

Mahayana practised in Nalanda and

Vajrayana, a

Tantra-influenced

version of Mahayanist philosophy. Nalanda was a cultural legacy from

the great age of the Guptas and it was prized and cherished. The Palas

were prolific builders and their rule oversaw the establishment of four

other Mahaviharas modelled on the Nalanda Mahavihara at

Jagaddala,

Odantapura,

Somapura, and

Vikramashila respectively. Remarkably, Odantapura was founded by

Gopala, the progenitor of the royal line, only 6 miles (9.7 km) away from Nalanda.

[10]:349–352

Inscriptions at Nalanda suggest that Gopala's son,

Dharmapala,

who founded the Mahavihara at Vikramshila, also appears to have been a

benefactor of the ancient monastery in some form. It is however,

Dharmapala's son, the 9th century emperor and founder of the Mahavihara

at Somapura,

Devapala,

who appears to have been Nalanda's most distinguished patron in this

age. A number of metallic figures containing references to Devapala have

been found in its ruins as well as two notable inscriptions. The first,

a

copper plate inscription unearthed at Nalanda, details an endowment by the

Shailendra King,

Balaputradeva of

Suvarnadvipa (

Sumatra in modern-day

Indonesia). This

Srivijayan

king, "attracted by the manifold excellences of Nalanda" had built a

monastery there and had requested Devapala to grant the revenue of five

villages for its upkeep, a request which was granted. The

Ghosrawan

inscription is the other inscription from Devapala's time and it

mentions that he received and patronised a learned Vedic scholar named

Viradeva who was later elected the head of Nalanda.

[4]:152[7]:58[22]:268

The now five different seats of Buddhist learning in eastern India

formed a state-supervised network and it was common for great scholars

to move easily from position to position among them. Each establishment

had its own official seal with a

dharmachakra flanked by a deer on either side, a motif referring to Buddha's deer park sermon at

Sarnath. Below this device was the name of the institution which in Nalanda's case read, "

Śrī-Nālandā-Mahāvihārīya-Ārya-Bhikṣusaḿghasya" which translates to "of the Community of Venerable Monks of the Great Monastery at Nalanda".

[10]:352[14]:55

While there is ample epigraphic and literary evidence to show that

the Palas continued to patronise Nalanda liberally, the Mahavihara was

less singularly outstanding during this period as the other Pala

establishments must have drawn away a number of learned monks from

Nalanda. The Vajrayana influence on Buddhism grew strong under the Palas

and this appears to have also had an effect on Nalanda. What had once

been a centre of liberal scholarship with a Mahayanist focus grew more

fixated with Tantric doctrines and magic rites. Taranatha's 17th-century

history claims that Nalanda might have even been under the control of

the head of the Vikramshila Mahavihara at some point.

[10]:344–346[14]:10

The Mahavihara

While its excavated ruins today only occupy an area of around 1,600

feet (488 m) by 800 feet (244 m) or roughly 12 hectares, Nalanda

Mahavihara occupied a far greater area in medieval times.

[7]:217

It was considered an architectural masterpiece, and was marked by a

lofty wall and one gate. Nalanda had eight separate compounds and ten

temples, along with many other meditation halls and classrooms. On the

grounds were lakes and parks.

[citation needed]

Nalanda was a residential school, i.e., it had dormitories for

students. In its heyday, it is claimed to have accommodated over 10,000

students and 2,000 teachers. Chinese pilgrims estimated the number of

students to have been between 3,000 and 5,000.

[23]

The subjects taught at Nalanda covered every field of learning, and

it attracted pupils and scholars from Korea, Japan, China, Tibet,

Indonesia,

Persia and

Turkey.

[24]

Xuanzang

left detailed accounts of the school in the 7th century. He described

how the regularly laid-out towers, forest of pavilions, harmikas and

temples seemed to "soar above the mists in the sky" so that from their

cells the monks "might witness the birth of the winds and clouds".

[25]:158

The pilgrim states: "An azure pool winds around the monasteries,

adorned with the full-blown cups of the blue lotus; the dazzling red

flowers of the lovely kanaka hang here and there, and outside groves of

mango trees offer the inhabitants their dense and protective shade."

[25]:159

Library

It is evident from the large numbers of texts that Yijing carried

back with him after his 10-year residence at Nalanda, that the

Mahavihara must have featured a well-equipped library. Traditional

Tibetan sources mention the existence of a great library at Nalanda

named

Dharmaganja (

Piety Mart) which comprised three large multi-storeyed buildings, the

Ratnasagara (

Ocean of Jewels), the

Ratnodadhi (

Sea of Jewels), and the

Ratnaranjaka (

Jewel-adorned). Ratnodadhi was nine storeys high and housed the most sacred manuscripts including the

Prajnyaparamita Sutra and the

Guhyasamaja.

[4]:159[6]:174

The exact number of volumes in the Nalanda library is not known. But it is estimated to have been in the hundreds of thousands.

[26] The library not only collected religious manuscripts but also had texts on such subjects as

grammar, logic, literature,

astrology,

astronomy, and medicine.

[27]

The Nalanda library must have had a classification scheme which was

possibly based on a text classification scheme developed by the Sanskrit

linguist,

Panini.

[28]:4 Buddhist texts were most likely divided into three classes based on the

Tripitaka's three main divisions: the

Vinaya,

Sutra, and the

Abhidhamma.

[29]:37

Curriculum

In his biography of Xuanzang, Hwui-Li states that all the students of

Nalanda studied the Great Vehicle (Mahayana) as well as the works of

the eighteen (

Hinayana) sects of Buddhism. In addition to these, they studied other subjects such as the

Vedas,

Hetuvidyā (Logic),

Shabdavidya (Grammar and Philology),

Chikitsavidya (Medicine), the works on magic (the

Atharvaveda), and

Samkhya.

[10]:332–333

Xuanzang himself studied a number of these subjects at Nalanda under Shilabhadra and others.

[7]:65

Besides Theology and Philosophy, frequent debates and discussions

necessitated competence in Logic. A student at the Mahavihara had to be

well-versed in the systems of Logic associated with all the different

schools of thought of the time as he was expected to defend Buddhist

systems against the others.

[7]:73 Other subjects believed to have been taught at Nalanda include law, astronomy, and city-planning.

[5]

Tibetan tradition holds that there were "four

doxographies" (Tibetan:

grub-mtha’) which were taught at Nalanda:

[30]

- Sarvastivada Vaibhashika

- Sarvastivada Sautrantika

- Madhyamaka, the Mahayana philosophy of Nagarjuna

- Chittamatra, the Mahayana philosophy of Asanga and Vasubandhu

In the 7th century,

Xuanzang

recorded the number of teachers at Nalanda as being around 1510. Of

these, approximately 1000 were able to explain 20 collections of sutras

and shastras, 500 were able to explain 30 collections, and only 10

teachers were able to explain 50 collections. Xuanzang was among the few

who were able to explain 50 collections or more. At this time, only the

abbot

Shilabhadra had studied all the major collections of sutras and shastras at Nalanda.

[31]

Administration

The Chinese monk

Yijing

wrote that matters of discussion and administration at Nalanda would

require assembly and consensus on decisions by all those at the

assembly, as well as resident monks:

[32]

If the monks had some business, they would assemble to discuss the

matter. Then they ordered the officer, Vihārpāl, to circulate and report

the matter to the resident monks one by one with folded hands. With the

objection of a single monk, it would not pass. There was no use of

beating or thumping to announce his case. In case a monk did something

without consent of all the residents, he would be forced to leave the

monastery. If there was a difference of opinion on a certain issue, they

would give reason to convince (the other group). No force or coercion

was used to convince.

Xuanzang also noted:

[25]:159

The lives of all these virtuous men were naturally governed by habits

of the most solemn and strictest kind. Thus in the seven hundred years

of the monastery's existence no man has ever contravened the rules of

the discipline. The king showers it with the signs of his respect and

veneration and has assigned the revenue from a hundred cities to pay for

the maintenance of the religious.

Influence on Buddhism

Buddha Shakyamuni or the Bodhisattva

Maitreya, gilt copper alloy, early 8th century, Nalanda

A vast amount of what came to comprise

Tibetan Buddhism, both its

Mahayana and

Vajrayana traditions, stems from the teachers and traditions at Nalanda.

Shantarakshita,

who pioneered the propagation of Buddhism in Tibet in the 8th century

was a scholar of Nalanda. He was invited by the Tibetan king,

Khri-sron-deu-tsan, and established the monastery at

Samye, serving as its first abbot. He and his disciple

Kamalashila (who was also of Nalanda) essentially taught Tibetans how to do philosophy.

[33] Padmasambhava, who was also invited from Nalanda Mahavihara by the king in 747 CE, is credited as a founder of Tibetan Buddhism.

[14]:11

The scholar

Dharmakirti (

c. 7th century), one of the Buddhist founders of Indian

philosophical logic, as well as one of the primary theorists of

Buddhist atomism, taught at Nalanda.

[34]

Other forms of Buddhism, such as the Mahayana Buddhism followed in Vietnam, China,

Korea

and Japan, flourished within the walls of the ancient school. A number

of scholars have associated some Mahayana texts such as the

Shurangama Sutra, an important sutra in East Asian Buddhism, with the Buddhist tradition at Nalanda.

[10]:264[35]

Ron Epstein also notes that the general doctrinal position of the sutra

does indeed correspond to what is known about the Buddhist teachings at

Nalanda toward the end of the Gupta period when it was translated.

[36]

Historical figures associated with Nalanda

Traditional sources state that Nalanda was visited by both

Mahavira and the

Buddha in

c. 6th and 5th century BCE.

[1] It is also the place of birth and nirvana of

Shariputra, one of the famous disciples of Buddha.

[4]:148

- Aryabhata[37]

- Aryadeva, student of Nagarjuna[8]:43

- Atisha, Mahayana and Vajrayana scholar

- Chandrakirti, student of Nagarjuna

- Dharmakirti, logician[34]

- Dharmapala

- Dignaga, founder of Buddhist Logic

- Nagarjuna, formaliser of the concept of Shunyata[8]:43

- Naropa, student of Tilopa and teacher of Marpa

- Shilabhadra, the teacher of Xuanzang[20]

- Xuanzang, Chinese Buddhist traveller[7]:191

- Yijing, Chinese Buddhist traveller[7]:197

Decline and end

The decline of Nalanda is concomitant with the disappearance of

Buddhism in India. When Xuanzang travelled the length and breadth of

India in the 7th century, he observed that his religion was in slow

decay and even had ominous premonitions of Nalanda's forthcoming demise.

[18]:145

Buddhism had steadily lost popularity with the laity and thrived,

thanks to royal patronage, only in the monasteries of Bihar and Bengal.

By the time of the Palas, the traditional Mahayana and Hinayana forms of

Buddhism were imbued with Tantric practices involving secret rituals

and magic. The rise of Hindu philosophies in the subcontinent and the

waning of the Buddhist Pala dynasty after the 11th century meant that

Buddhism was hemmed in on multiple fronts, political, philosophical, and

moral. The final blow was delivered when its still-flourishing

monasteries, the last visible symbols of its existence in India, were

overrun during the Muslim invasion that swept across Northern India at

the turn of the 13th century.

[7]:208[14]:13[22]:333[38]

In around 1200 CE,

Bakhtiyar Khilji, a

Turkic chieftain out to make a name for himself, was in the service of a commander in

Awadh. The Persian historian,

Minhaj-i-Siraj in his

Tabaqat-i Nasiri,

recorded his deeds a few decades later. Khilji was assigned two

villages on the border of Bihar which had become a political no-man's

land. Sensing an opportunity, he began a series of plundering raids into

Bihar and was recognised and rewarded for his efforts by his superiors.

Emboldened, Khilji decided to attack a fort in Bihar and was able to

successfully capture it, looting it of a great booty.

[13] Minhaj-i-Siraj wrote of this attack:

[39]

Muhammad-i-Bakht-yar, by the force of his intrepidity, threw himself

into the postern of the gateway of the place, and they captured the

fortress, and acquired great booty. The greater number of the

inhabitants of that place were Brahmans, and the whole of those Brahmans

had their heads shaven; and they were all slain. There were a great

number of books there; and, when all these books came under the

observation of the Musalmans, they summoned a number of Hindus that they

might give them information respecting the import of those books; but

the whole of the Hindus had been killed. On becoming acquainted [with

the contents of those books], it was found that the whole of that

fortress and city was a college, and in the Hindui tongue, they call a

college [مدرسه] Bihar.

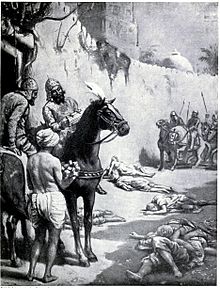

The End of the Buddhist Monks, A.D. 1193 from Hutchinson's Story of the Nations depicts Khilji trying to make sense of a manuscript.

This passage refers to an attack on a Buddhist monastery (the "Bihar" or

Vihara)

and its monks (the shaved Brahmans). The exact date of this event is

not known with scholarly estimates ranging from 1197 to 1206. While many

historians believe that this monastery which was mistaken for a fort

was Odantapura, some are of the opinion that it was Nalanda itself.

[13] However, considering that these two Mahaviharas were only a few kilometres apart, both very likely befell a similar fate.

[7]:212[14]:14

The other great Mahaviharas of the age such as Vikramshila and later,

Jagaddala, also met their ends at the hands of the Turks at around the

same time.

[10]:157,379

Another important account of the times is the biography of the Tibetan monk-pilgrim,

Dharmasvamin,

who journeyed to India between 1234 and 1236. When he visited Nalanda

in 1235, he found it still surviving, but a ghost of its past existence.

Most of the buildings had been damaged by the Muslims and had since

fallen into disrepair. But two viharas, which he named

Dhanaba and

Ghunaba, were still in serviceable condition with a 90-year-old teacher named

Rahula Shribhadra instructing a class of about 70 students on the premises.

[4]:150

Dharmasvamin believed that the Mahavihara had not been completely

destroyed for superstitious reasons as one of the soldiers who had

participated in the desecration of a Jnananatha temple in the complex

had immediately fallen ill.

[40]

While he stayed there for six months under the tutelage of Rahula

Shribhadra, Dharmasvamin makes no mention of the legendary library of

Nalanda which possibly did not survive the initial wave of Turkic

attacks. He, however, provides an eyewitness account of an attack on the

derelict Mahavihara by the Muslim soldiers stationed at nearby

Odantapura (now

Bihar Sharif)

which had been turned into a military headquarters. Only the Tibetan

and his nonagenarian instructor stayed behind and hid themselves while

the rest of the monks fled Nalanda.

[10]:347[40]

Contemporary sources end at this point. But traditional Tibetan works

which were written much later suggest that Nalanda's story might have

managed to endure for a while longer even if the institution was only a

pale shadow of its former glory. The Lama, Taranatha, states that the

whole of Magadha fell to the Turks who destroyed many monasteries

including Nalanda which suffered heavy damage. He however also notes

that a king of Bengal named

Chagalaraja and his queen later patronised Nalanda in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, although no major work was done there.

[4]:151

An 18th-century work named

Pag sam jon zang recounts another

Tibetan legend which states that chaityas and viharas at Nalanda were

repaired once again by a Buddhist sage named Mudita Bhadra and that

Kukutasiddha, a minister of the reigning king, erected a temple there. A

story goes that when the structure was being inaugurated, two indignant

(Brahmanical)

Tirthika

mendicants who had appeared there were treated with disdain by some

young novice monks who threw washing water at them. In retaliation, the

mendicants performed a 12-year penance propitiating the sun, at the end

of which they performed a fire-sacrifice and threw "living embers" from

the sacrificial pit into the Buddhist temples. The resulting

conflagration is said to have hit Nalanda's library. Fortunately, a

miraculous stream of water gushed forth from holy manuscripts in the

ninth storey of Ratnodadhi which enabled many manuscripts to be saved.

The heretics perished in the very fire that they had kindled.

[7]:208[10]:343[14]:15

While it is unknown when this event was supposed to have occurred,

archaeological evidence (including a small heap of burnt rice) does

suggest that a large fire did consume a number of structures in the

complex on more than one occasion.

[7]:214[14]:56 A stone inscription notes the destruction by fire and subsequent restoration at the Mahavihara during the reign of

Mahipala (

r. 988 –

1038).

[14]:13

The last throne-holder of Nalanda,

Shakyashribhadra, fled to Tibet in 1204 at the invitation of the Tibetan translator

Tropu Lotsawa (

Khro-phu Lo-tsa-ba Byams-pa dpal). In Tibet, he started an ordination lineage of the

Mulasarvastivada lineage to complement the two existing ones.

[citation needed]

The remains

Excavated ruins of the monasteries of Nalanda.

After its decline, Nalanda was largely forgotten until

Francis Buchanan-Hamilton

surveyed the site in 1811–1812 after locals in the vicinity drew his

attention to a vast complex of ruins in the area. He, however, did not

associate the mounds of earth and debris with famed Nalanda. That link

was established by Major Markham Kittoe in 1847.

Alexander Cunningham and the newly formed

Archaeological Survey of India conducted an official survey in 1861–1862.

[2]:59

Systematic excavation of the ruins by the ASI did not begin until 1915

and ended in 1937. A second round of excavation and restoration took

place between 1974 and 1982.

[1]

The remains of Nalanda today extend some 1,600 feet (488 m) north to

south and around 800 feet (244 m) east to west. Excavations have

revealed eleven monasteries and six major brick temples arranged in an

ordered layout. A 100 ft (30 m) wide passage runs from north to south

with the temples to its west and the monasteries to its east.

[1][7]:217

Most structures show evidence of multiple periods of construction with

new buildings being raised atop the ruins of old ones. Many of the

buildings also display signs of damage by fire on at least one occasion.

[14]:27

All the monasteries at Nalanda are very similar in layout and general

appearance. Their plan involves a rectangular form with a central

quadrangular court which is surrounded by a verandah which, in turn, is

bounded by an outer row of cells for the monks. The central cell facing

the entrance leading into the court is a shrine chamber. Its strategic

position means that it would have been the first thing that drew the eye

when entering the edifice. With the exception of those designated 1A

and 1B, the monasteries all face west with drains emptying out in the

east and staircases positioned in the south-west corner of the

buildings.

[7]:219[14]:28

Monastery 1 is considered the oldest and the most important of the

monastery group and shows as many as nine levels of construction. Its

lower monastery is believed to be the one sponsored by Balaputradeva,

the Srivijayan king, during the reign of Devapala in the 9th century.

The building was originally at least 2 storeys high and contained a

colossal statue of a seated Buddha.

[14]:19

A map of the excavated remains of Nalanda.

The most iconic of Nalanda's structures is Temple no. 3 with its

multiple flights of stairs that lead all the way to the top. The temple

was originally a small structure which was built upon and enlarged by

later constructions. Archaeological evidence shows that the final

structure was a result of at least seven successive such accumulations

of construction. The fifth of these layered temples is the most

interesting and the best preserved with four corner towers of which

three have been exposed. The towers as well as the sides of the stairs

are decorated with exquisite panels of Gupta-era art depicting a variety

of stucco figures including Buddha and the

Bodhisattvas, scenes from the

Jataka tales, Brahmanical deities such as

Shiva,

Parvati,

Kartikeya, and

Gajalakshmi,

Kinnaras playing musical instruments, various representations of

Makaras,

as well as human couples in amorous postures. The temple is surrounded

by numerous votive stupas some of which have been built with bricks

inscribed with passages from sacred Buddhist texts. The apex of Temple

no. 3 features a shrine chamber which now only contains the pedestal

upon which an immense statue of Buddha must have once rested.

[7]:222[14]:17

Temple no. 2 notably features a

dado

of 211 sculptured panels depicting a variety of religious motifs as

well as scenes of art and of everyday life. The site of Temple no. 13

features a brick-made smelting furnace with four chambers. The discovery

of burnt metal and

slag

suggests that it was used to cast metallic objects. To the north of

this temple lie the remains of Temple no. 14. An enormous image of the

Buddha was discovered here. The image's pedestal features fragments of

the only surviving exhibit of mural painting at Nalanda.

[14]:31–33

Numerous sculptures, murals, copper plates, inscriptions, seals,

coins, plaques, potteries and works in stone, bronze, stucco and

terracotta have been unearthed within the ruins of Nalanda. The Buddhist

sculptures discovered notably include those of the Buddha in different

postures,

Avalokiteshvara,

Jambhala,

Manjushri,

Marichi, and

Tara. Brahmanical idols of

Vishnu, Shiva-Parvathi,

Ganesha,

Mahishasura Mardini, and

Surya have also been found in the ruins.

[1]

A number of other ruined structures survive. Nearby is the

Surya Mandir, a

Hindu temple.

[citation needed] The known and excavated

ruins extend over an area of about 150,000 square metres, although if

Xuanzang's account of Nalanda's extent is correlated with present excavations, almost 90% of it remains unexcavated.

[citation needed] Nalanda is no longer inhabited. Today the nearest habitation is a village called

Bargaon.

Surviving Nalanda manuscripts

Fleeing monks took some of the Nalanda manuscripts. A few of them

have survived and are preserved in collections such as those at:

Revival efforts

In 1951, the

Nava Nalanda Mahavihara (

New Nalanda Mahavihara), a modern centre for

Pali and

Buddhism in the spirit of the ancient institution, was founded by the

Government of Bihar near Nalanda's ruins.

[44] It was

deemed to be a university in 2006.

[45]

September 1, 2014, saw the commencement of the first academic year of a modern

Nalanda University, with 15 students, in nearby

Rajgir.

[46]

It has been established in a bid to revive the ancient seat of

learning. The university has acquired 455 acres of land for its campus

and has been allotted ₹2727 crores (around $454M) by the Indian

government.

[47] It is also being funded by the governments of China, Singapore, Australia, Thailand, and others.

[48]

Tourism

Nalanda is a popular tourist destination in the state attracting a number of Indian and overseas visitors.

[49] It is also an important stop on the Buddhist tourism circuit.

[48]

Nalanda Archaeological Museum

The

Archaeological Survey of India

maintains a museum near the ruins for the benefit of visitors. The

museum exhibits the antiquities that have been unearthed at Nalanda as

well as from nearby

Rajgir. Out of 13,463 items, only 349 are on display in four galleries.

[50]

Xuanzang Memorial Hall

The Xuanzang Memorial Hall at Nalanda

The Xuanzang Memorial Hall is an Indo-Chinese undertaking to honour

the famed Buddhist monk and traveller. A relic, comprising a skull bone

of the Chinese monk, is on display in the memorial hall.

[51]

Nalanda Multimedia Museum

Another museum adjoining the excavated site is the privately run Nalanda Multimedia Museum.

[52] It showcases the history of Nalanda through

3-D animation and other multimedia presentations.

Gallery

|

|

A sign detailing the history of Nalanda.

|

|

|

A teaching platform in the ruins of Nalanda

|

|

|

Sculpted stucco panels on a tower

|

|

See also

References

No comments:

Post a Comment