begin quote from:

"UK EU referendum" redirects here. For the 1975 referendum on remaining in the EEC, see United Kingdom European Communities membership referendum, 1975.

| United Kingdom European Union membership referendum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | United Kingdom and Gibraltar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Date | 23 June 2016 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

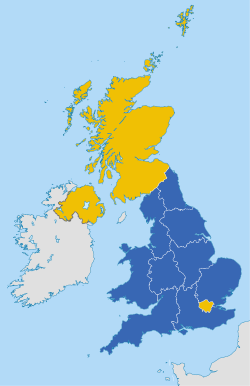

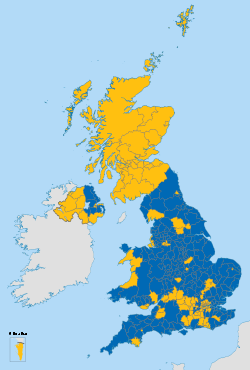

| On the map, the darker shades for a colour indicate a larger margin. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series of articles on the |

| United Kingdom in the European Union |

|---|

|

Membership of the EU and its predecessors had long been a topic of debate in the United Kingdom. The country joined the European Economic Community (EEC, or "Common Market") in 1973. A referendum on continued EEC membership was held in 1975, and it was approved by 67% of voters.[11] In accordance with a Conservative Party manifesto commitment, the legal basis for a referendum was established by the UK Parliament through the European Union Referendum Act 2015.

Britain Stronger in Europe was the official group campaigning for the UK to remain in the EU, and Vote Leave the official group campaigning for it to leave. Other campaign groups, political parties, businesses, trade unions, newspapers and prominent individuals were also involved, and each side had supporters from across the political spectrum.

Those who favoured a British withdrawal from the European Union – commonly referred to as a Brexit (a portmanteau of "British" and "exit")[12][a] – argued that the EU has a democratic deficit and that being a member undermined national sovereignty, while those who favoured membership argued that in a world with many supranational organisations any loss of sovereignty was compensated by the benefits of EU membership. Those who wanted to leave the EU argued that it would allow the UK to better control immigration, thus reducing pressure on public services, housing and jobs; save billions of pounds in EU membership fees; allow the UK to make its own trade deals; and free the UK from EU regulations and bureaucracy that they saw as needless and costly. Those who wanted to remain argued that leaving the EU would risk the UK's prosperity; diminish its influence over world affairs; jeopardise national security by reducing access to common European criminal databases; and result in trade barriers between the UK and the EU. In particular, they argued that it would lead to job losses, delays in investment into the UK and risks to business.[14]

Financial markets reacted negatively to the outcome.[15] Investors in worldwide stock markets lost more than the equivalent of 2 trillion United States dollars on 24 June 2016, making it the worst single-day loss in history, in absolute terms.[16] The market losses amounted to 3 trillion US dollars by 27 June.[17] The value of the pound sterling against the US dollar fell to a 31-year low.[18] The UK's and the EU's sovereign debt credit rating was also lowered by Standard & Poor's.[19][20] By 29 June, the markets had returned to growth and the value of the pound had begun to rise.[21]

Immediately following the result, the Prime Minister David Cameron announced he would resign, having campaigned unsuccessfully for a "remain" vote. The opposition Labour Party also faces a leadership challenge as a result of the EU referendum.[22] In response to the result, the Scottish Government announced that it would plan for a possible second referendum on independence from the United Kingdom,[23] and announced that it would like "discussions with the EU institutions and other member states to explore all the possible options to protect Scotland's place in the EU".[24]

On Wednesday 13 July 2016 almost three weeks after the vote Theresa May succeeded David Cameron to become only the second women to hold the post of Prime Minister.

Contents

- 1 History

- 2 Renegotiation before the referendum

- 3 Legislation

- 4 Administration

- 5 Campaign

- 6 Responses to the referendum campaign

- 7 Opinion polling

- 8 Issues

- 9 Debates, Q&A sessions and interviews

- 10 Voting, voting areas and counts

- 11 Disturbances

- 12 Voting results

- 13 Reactions to the result

- 14 See also

- 15 Notes

- 16 References

- 17 Further reading

- 18 External links

History

See also: European Communities Act 1972 (UK) and European Union Act 2011

The European Economic Community (EEC) was formed in 1957.[25] The United Kingdom (UK) first applied to join in 1961, but this was vetoed by France.[25] A later application was successful and the UK joined in 1973; a referendum two years later on continuing membership resulted in 67% approval.[25] Political integration gained greater focus when the Maastricht Treaty established the European Union (EU) in 1993, which incorporated (and after the Treaty of Lisbon, succeeded) the EEC.[25][26]

In his 2015 election campaign, David Cameron promised to renegotiate the EU membership and later hold a referendum.

While attending the May 2012 NATO summit meeting, British Prime Minister David Cameron, William Hague and Ed Llewellyn discussed the idea of using a European Union referendum as a concession to energise the Eurosceptic wing of the Conservative Party.[28] In January 2013, Cameron promised that, should his Conservative Party win a parliamentary majority at the 2015 general election, the UK Government would negotiate more favourable arrangements for continuing British membership of the EU, before holding a referendum on whether the UK should remain in or leave the EU.[29] In May 2013, the Conservative Party published a draft EU Referendum Bill and outlined their plans for renegotiation and then an In-Out vote if returned to office in 2015.[30] The draft Bill stated that the referendum must be held no later than 31 December 2017.[31]

The draft legislation was taken forward as a Private Member's Bill by Conservative MP James Wharton.[32] The bill's First Reading in the House of Commons took place on 19 June 2013.[33] Cameron was said by a spokesperson to be "very pleased" and would ensure the Bill was given "the full support of the Conservative Party".[34]

Regarding the ability of the Bill to bind the UK Government in the 2015–20 Parliament to holding such a referendum, a parliamentary research paper noted that:

The Bill simply provides for a referendum on continued EU membership by the end of December 2017 and does not otherwise specify the timing, other than requiring the Secretary of State to bring forward orders by the end of 2016. [...] If no party obtained a majority at the [next general election due in 2015], there might be some uncertainty about the passage of the orders in the next Parliament.[35]The Bill received its Second Reading on 5 July 2013, passing by 304 votes to none after almost all Labour MPs and all Liberal Democrat MPs abstained, cleared the Commons in November 2013, and was then introduced to the House of Lords in December 2013, where members voted to block the bill.[36]

Conservative MP Bob Neill then introduced an Alternative Referendum Bill to the Commons.[37][38] After a debate on 17 October 2014, it passed to the Public Bills Committee, but because the Commons failed to pass a money resolution, the Bill was unable to progress further before the Dissolution of Parliament on 27 March 2015.[39][40]

Under Ed Miliband's leadership between 2010 and 2015, the Labour Party ruled out an In-Out referendum unless and until a further transfer of powers from the UK to the EU were proposed.[41] In their manifesto for the 2015 general election the Liberal Democrats pledged to hold an In-Out referendum only in the event of there being a change in the EU treaties.[42] The UK Independence Party (UKIP), the British National Party (BNP), the Green Party,[43] the Democratic Unionist Party[44] and the Respect Party[45] all supported the principle of a referendum.

When the Conservative Party won the majority of seats in the House of Commons in the May 2015 general election, Cameron reiterated his party's manifesto commitment to hold an In-Out referendum on UK membership of the EU by the end of 2017, but only after "negotiating a new settlement for Britain in the EU".[46]

Renegotiation before the referendum

Main article: UK renegotiation of EU membership, 2016

In early 2014, Prime Minister David Cameron outlined the changes he

aimed to bring about in the EU and in the UK's relationship with it.[47]

These were: additional immigration controls, especially for new EU

members; tougher immigration rules for present EU citizens; new powers

for national parliaments collectively to veto proposed EU laws; new free

trade agreements and a reduction in bureaucracy for businesses; a

lessening of the influence of the European Court of Human Rights

on UK police and courts; more power for individual member states and

less for the central EU; and abandoning the EU notion of "ever closer

union".[47]

He intended to bring these about during a series of negotiations with

other EU leaders and then, if re-elected, to announce a referendum.[47]In November that year, Cameron gave an update on the negotiations and further details of his aims.[48] The key demands made of the EU were: on economic governance, to recognise officially that Eurozone laws would not necessarily apply to non-Eurozone EU members and the latter would not have to bail out troubled Eurozone economies; on competitiveness, to expand the single market and to set a target for the reduction of bureaucracy for businesses; on sovereignty, for the UK to be legally exempted from "ever closer union" and for national parliaments to be able collectively to veto proposed EU laws; and, on immigration, for EU citizens going to the UK for work to be unable to claim social housing or in-work benefits until they had worked there for four years and for them to be unable to send child benefit payments overseas.[48][49]

The outcome of the renegotiations was announced in February 2016.[50] The renegotiated terms were in addition to the United Kingdom's existing opt-outs in the European Union and the UK rebate. There was no fundamental change to the EU–UK relationship.[50][citation needed] Some limits to in-work benefits for EU immigrants were agreed, but these would apply on a sliding scale for four years and be for new immigrants only; before they could be applied, a country would have to get permission from the European Council.[50] Child benefit payments could still be made overseas, but these would be linked to the cost of living in the other country.[51] On sovereignty, the UK was reassured that it would not be required to participate in "ever closer union"; these reassurances were "in line with existing EU law".[50] Cameron's demand to allow national parliaments to veto proposed EU laws was modified to allow national parliaments collectively to object to proposed EU laws, in which case the European Council would reconsider the proposal before itself deciding what to do.[50] On economic governance, anti-discrimination regulations for non-Eurozone members would be reinforced, but they would be unable to veto any legislation.[52] The final two areas covered were proposals to "exclude from the scope of free movement rights, third country nationals who had no prior lawful residence in a Member State before marrying a Union citizen"[53] and to make it easier for member states to deport EU nationals for public policy or public security reasons.[54] The extent to which the various parts of the agreement would be legally binding is complex; no part of the agreement itself changed EU law, but some parts could be enforceable in international law.[55]

A report in The Guardian of 28 June 2016 indicates that EU staffers were "bitter and disappointed" that David Cameron had failed to use the "very generous deal" offered to the UK in February to achieve success for the Remain campaign.[56] In any event, the deal was discarded soon after the UK voted to leave the European Union.[57]

Legislation

To enable the referendum to take place across the United Kingdom and Gibraltar, two pieces of legislation were enacted. The first of these, the European Union Referendum Act 2015, was passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom and received the Royal Assent on 17 December 2015. The second, the European Union (Referendum) Act 2016, was passed by the Gibraltar Parliament to allow the referendum to take place in Gibraltar and received the Royal Assent on 28 January 2016.[citation needed]The planned referendum was included in the Queen's Speech on 27 May 2015.[58] It was suggested at the time that Cameron was planning to hold the referendum in October 2016,[59] but the European Union Referendum Act 2015, which authorised it, went before the House of Commons the following day, just three weeks after the election.[60] On the bill's second reading on 9 June, members of the House of Commons voted by 544 to 53 in favour of it, endorsing the principle of holding a referendum, with only the Scottish National Party voting against.[61] In contrast to the Labour Party's position prior to the 2015 general election under Miliband, acting Labour leader Harriet Harman committed her party to supporting plans for an EU referendum by 2017.[62]

Administration

Date

Prior to being officially announced, it was widely speculated that a June date for the referendum was a serious possibility. The First Ministers of Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales co-signed a letter to Cameron asking him not to hold the referendum in June, as devolved elections were scheduled to take place the previous month. These elections had been postponed for a year to avoid a clash with the 2015 General Election, after Westminster had implemented the Fixed Term parliament Act. Cameron refused this request, saying people were able to make up their own minds in multiple elections spaced a short time from each other.[63]In February 2016, Cameron announced that the Government was to recommend that the UK should remain in the EU and that the referendum would be held on 23 June, marking the official launch of the campaign. He also announced that Parliament would enact secondary legislation relating to the European Union Referendum Act 2015 on 22 February. With the official launch, ministers of the UK Government were then free to campaign on either side of the argument in a rare exception to Cabinet collective responsibility.[64]

Eligibility to vote

The European Union Referendum Act 2015 dictated that only British, Irish and Commonwealth citizens over 18 who were resident in the UK or Gibraltar would be able to vote in the referendum.[65] British citizens who had been registered to vote in the UK within the last 15 years would also be eligible to vote.[65]The deadline to register to vote was initially midnight on 7 June 2016 but this was extended by 48 hours because of technical problems with the official registration website on 7 June caused by unusually high web traffic. Some supporters of the Leave campaign, including the Conservative MP Sir Gerald Howarth, criticised the government's decision to extend the deadline, alleging it gave Remain an advantage because many late registrants were young people who were considered to be more likely to vote for Remain.[66] Almost 46.5 million people were eligible to vote.[67]

There was protest by some residents of the Crown dependencies of the Isle of Man, Jersey and Guernsey that they should have the opportunity to vote in the referendum, as (although not part of the EU, unlike Gibraltar) EU membership also affected them.[68]

Procedure for a withdrawal

There is no precedent for a sovereign member state leaving the European Union or any of its predecessor organisations. However, three territories of EU member states have withdrawn: Algeria (1962, independence from France),[69] Greenland (1985)[70] and Saint Barthélemy (2012),[71] the latter two becoming Overseas Countries and Territories of the European Union.Article 49A of the Treaty of Lisbon, which came into force on 1 December 2009, introduced for the first time a procedure for a member state to withdraw voluntarily from the EU.[72] This is specified in Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union, which states that:[73]

Coverage of the issue in The Guardian includes an explanation as to Article 50 and how it would be invoked. "...there seems to be no immediate legal means out of the stalemate. It is entirely up to the departing member state to trigger article 50, by issuing formal notification of intention to leave: no one, in Brussels, Berlin or Paris, can force it to. But equally, there is nothing in article 50 that obliges the EU to start talks – including the informal talks the Brexit leaders want – before formal notification has been made. "There is no mechanism to compel a state to withdraw from the European Union," said Kenneth Armstrong, professor of European law at Cambridge University. ... "The notification of article 50 is a formal act and has to be done by the British government to the European council," an EU official told Reuters."[74]

- Any Member State may decide to withdraw from the Union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements.

- A Member State which decides to withdraw shall notify the European Council of its intention. In the light of the guidelines provided by the European Council, the Union shall negotiate and conclude an agreement with that State, setting out the arrangements for its withdrawal, taking account of the framework for its future relationship with the Union. That agreement shall be negotiated in accordance with Article 218(3) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. It shall be concluded on behalf of the Union by the Council, acting by a qualified majority, after obtaining the consent of the European Parliament.

- The Treaties shall cease to apply to the State in question from the date of entry into force of the withdrawal agreement or, failing that, two years after the notification referred to in paragraph 2, unless the European Council, in agreement with the Member State concerned, unanimously decides to extend this period.

Remaining members of the EU consequently would need to undertake negotiations to manage change over the EU's budgets, voting allocations and policies brought about by the withdrawal of any member state.[75]

Some constitutional experts have argued that, under the Scotland Act 1998, the Scottish Parliament has to consent to measures that eliminate EU law's application in Scotland, which gives the Scottish Parliament an effective veto over UK withdrawal from the EU,[76] unless the Scotland Act 1998 is amended by the UK Parliament to reduce the Scottish Parliament's current powers.[77] After the Leave result was announced, on 26 June 2016, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said she "of course" would ask the Scottish Parliament to withhold consent and thus block the UK from leaving the EU.[78] However, this interpretation of the 1998 Act is disputed. For example, sub-clause 7 of Clause 28 of the Act states that it "does not affect the power of the Parliament of the United Kingdom to make laws for Scotland."[79]

Referendum wording

Sample referendum ballot paper

Scotland's response

After the referendum, there was a dispute as to whether, under the Scotland Act 1998, the Scottish Parliament has to consent to measures that eliminate EU laws' application in Scotland or whether Westminster can override this.[77][79][82][83]On 24 June, during a press conference, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said she would communicate to all EU member states that Scotland had voted to stay in the EU.[84] An emergency Scottish cabinet meeting on 25 June agreed that the Scottish Government would "begin immediate discussions with the EU institutions and other member states to explore all the possible options to protect Scotland's place in the EU."[24][85]

Sturgeon had called the result of the UK referendum "democratically unacceptable" for Scotland where the majority had voted to remain in the European Union. On 28 June 2016, she made the following statement: "I want to be clear to parliament that whilst I believe that independence is the best option for Scotland – I don’t think that will come as a surprise to anyone – it is not my starting point in these discussions. My starting point is to protect our relationship with the EU."[86] Sturgeon met with EU leaders in Brussels on 29 June to discuss Scotland remaining in the UK. Afterwards, she said the reception had been "sympathetic", in spite of France and Spain objecting to advance negotiations with Scotland, but she conceded that she did not underestimate the challenges.[87]

Campaign

Britain Stronger in Europe campaigners, London, June 2016

Referendum posters for both the Leave and Remain campaigns in Pimlico, London

HM Government distributed a leaflet to every household in England in the week commencing on 11 April, and in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland on 5 May (after devolved elections). It gave details on why the government's position was that the UK should remain in the EU. The rationale was that internal polls showed that 85% of the population wanted more information from the Government.[94] It was criticised by those wanting to leave as being an unfair advantage, inaccurate and a waste of money costing £9.3 million for the campaign.[95]

In the week beginning on 16 May the Electoral Commission sent a voting guide regarding the referendum to every household within the UK and Gibraltar to raise awareness of the upcoming referendum. The eight-page guide contained details on how to vote, as well as a sample of the actual ballot paper, and a whole page each was given to the campaign groups Britain Stronger in Europe and Vote Leave to present their case.[96][97]

Responses to the referendum campaign

Party policies

The table lists only those political parties with elected representation in the Westminster, the devolved and the European parliaments.| Position | Political parties | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remain | Alliance Party of Northern Ireland | [98][99] | |

| Green Party of England and Wales | [100] | ||

| Green Party in Northern Ireland | [101] | ||

| Labour Party | [102][103] | ||

| Liberal Democrats | [104] | ||

| Plaid Cymru – The Party of Wales | [105] | ||

| Scottish Green Party | [106] | ||

| Scottish National Party (SNP) | [107][108] | ||

| Sinn Féin | [109] | ||

| Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) | [110] | ||

| Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) | [111] | ||

| Leave | |||

| Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) | [112][113] | ||

| People Before Profit Alliance (PBP) | [114] | ||

| Traditional Unionist Voice (TUV) | [115] | ||

| UK Independence Party (UKIP) | [116] | ||

| Neutral | Conservative Party | [117] | |

All parties represented in the Gibraltar Parliament supported Remain: the Gibraltar Social Democrats (GSD),[128] the Gibraltar Socialist Labour Party (GSLP),[129] and the Liberal Party of Gibraltar.[129]

No party had decreed that its members should all follow the party line, resulting in public differences of view: Conservative Party MPs in particular, and Labour MPs to a lesser extent, taking different sides. Most parties had splits in their members and supporters, with Labour,[130] Conservative,[131] Liberal Democrat,[132] UKIP,[133] and Green[134] supporters all taking different sides.

Cabinet ministers

For the positions of backbench MPs and other politicians, see Endorsements in the United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, 2016.

The Cabinet of the United Kingdom is a body responsible for making decisions on policy and organising governmental departments; it is chaired by the Prime Minister and contains most of the government's ministerial heads.[135]

Following the announcement of the referendum in February, 23 of the 30

Cabinet ministers (including attendees) supported the UK staying in the

EU.[136] Iain Duncan Smith, in favour of leaving, resigned on 19 March and was replaced by Stephen Crabb who was in favour of remaining.[136][137] Crabb was already a cabinet member, as the Secretary of State for Wales, and his replacement, Alun Cairns, was in favour of remaining, bringing the total number of pro-remain Cabinet members to 25.Business

See also: Opinion polling for the United Kingdom European Union membership referendum § Business leaders

Various UK multinationals have stated that they would not like the UK

to leave the EU because of the uncertainty it would cause, such as Shell,[138] BT[139] and Vodafone,[140] with some assessing the pros and cons of Britain exiting.[141] The banking sector was one of the most vocal advocating to stay in the EU, with the British Bankers' Association saying: "Businesses don't like that kind of uncertainty".[142] RBS has warned of potential damage to the economy.[143] Furthermore, HSBC and foreign-based banks JP Morgan and Deutsche Bank claim a Brexit might result in the banks' changing domicile.[144][145] According to Goldman Sachs and the City of London's

policy chief, all such factors could impact on the City of London's

present status as a European and global market leader in financial

services.[146][147] In February 2016, leaders of 36 of the FTSE 100 companies, including Shell, BAE Systems, BT and Rio Tinto, officially supported staying in the EU.[148] Moreover, 60% of the Institute of Directors and the EEF memberships supported staying.[149]Many UK-based businesses, including Sainsbury's, remained steadfastly neutral, concerned that taking sides in the divisive issue could lead to a backlash from customers.[150]

Richard Branson stated that he was "very fearful" of the consequences of a UK exit from the EU.[151] Alan Sugar expressed similar concern.[152]

In June 2016, James Dyson, founder of the Dyson company, argued that the introduction of tariffs would be less damaging for British exporters than the appreciation of the pound against the Euro, arguing that, as Britain ran a 100 billion pound trade deficit with the EU, tariffs could represent a significant revenue source for the Treasury.[153] Pointing out that languages, plugs and laws differ between EU member states, Dyson said that the 28-country bloc was not a single market, and argued the fastest growing markets were outside the EU.[153] Engineering company Rolls-Royce wrote to employees to say that it did not want the UK to leave the EU.[154]

Surveys of large UK businesses showed a strong majority favour the UK remaining in the EU.[155] Small and medium-sized UK businesses are more evenly split.[155] Polls of foreign businesses found that around half would be less likely to do business in the UK, while 1% would increase their investment in the UK.[156][157][158] Two large car manufacturers – Ford and BMW – warned in 2013 against Brexit, suggesting it would be "devastating" for the economy.[159] Conversely, in 2015, some other manufacturing executives told Reuters that they would not shut their plants if the UK left the EU, although future investment might be put at risk.[160] The CEO of Vauxhall stated that a Brexit would not materially affect its business.[161] Foreign-based Toyota CEO Akio Toyoda confirmed that, whether or not Britain left the EU, Toyota would carry on manufacturing cars in Britain as they had done before.[162]

Exchange rates and stock markets

In the week following conclusion of the UK's renegotiation (and especially after Boris Johnson announced that he would support the UK leaving), the pound fell to a seven-year low against the dollar and economists at HSBC warned that it could drop even more.[163] At the same time, Daragh Maher, head of HSBC, suggested that if Sterling dropped in value so would the Euro. He said "If we have increased Brexit risk, we will have a negative risk for the euro." European banking analysts also cited Brexit concerns as the reason for the Euro's decline.[164] Immediately after a poll in June 2016 showed that the Leave campaign was 10 points ahead, the pound dropped by a further one per cent.[165] In the same month, it was announced that the value of goods exported from the UK in April had shown a month-on-month increase of 11.2%, "the biggest rise since records started in 1998".[166][167]Uncertainty over the referendum result, together with several other factors – US interest rates rising, low commodity prices, low Eurozone growth and concerns over emerging markets such as China – contributed to a high level of stock market volatility in January and February 2016.[168] During this period, the FTSE 100 rose or fell by more than 1.5% on 16 days.[168] On 14 June, polls showing that a Brexit was more likely led to the FTSE 100 falling by 2%, lost £98 billion in value.[169][170] After further polls suggested a move back towards Remain, the pound and the FTSE recovered.[171]

On the day of the referendum, Sterling hit a 2016 high and the FTSE 100 climbed to a 2016 high of $1.5018 as a new poll suggested a win for the Remain campaign.[172] Initial results suggested a vote for 'remain' and the value of the pound held its value. However, when the result for Sunderland was announced, it indicated an unexpected swing to 'leave'. Subsequent results appeared to confirm this swing and sterling fell in value to $1.3777, its lowest level since 1985. However, the following Monday when the markets opened, Sterling fell to a new low of $1.32.[173]

When the London Stock Exchange opened on the morning of 24 June, the FTSE 100 fell from 6338.10 to 5806.13 in the first ten minutes of trading. It recovered to 6091.27 after a further 90 minutes before further recovering to 6162.97 by the end of the day's trading. When the markets reopened the Following Monday, the FTSE 100 showed a steady decline losing over 2% by mid-afternoon.[174] Upon opening later on the Friday after the referendum, the US Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped nearly 450 points or about 2½% in less than half an hour. The Associated Press called the sudden worldwide stock market decline a stock market crash.[15]

By mid afternoon on 27 June 2016, the sterling was at a 31-year low, having fallen 11% in two trading days and the FTSE 100 had surrendered £85 billion,[175] though by 29 June it had recovered all its losses since the markets closed on polling day.[176]

European responses

Czech prime minister Bohuslav Sobotka suggested that the Czech Republic would start discussions on leaving the EU if the UK voted for an EU exit.[177] Former Czech President Václav Klaus said that Britain's departure from the EU would be a bigger non-event than the dissolution of Czechoslovakia.[178]Marine Le Pen, the leader of the French Front national, described the possibility of a Brexit as "like the fall of the Berlin Wall" and commented that "Brexit would be marvellous – extraordinary – for all European peoples who long for freedom".[179] A poll in France showed that 59% of the French people were in favour of Britain remaining in the EU.[180]

Polish President Andrzej Duda lent his support for the UK remaining within the EU.[181] Moldovan Prime Minister Pavel Filip asked all citizens of Moldova living in the UK to speak to their British friends and convince them to vote for the UK to remain in the EU.[182]

Spanish foreign minister José García-Margallo said Spain would demand control of Gibraltar the "very next day" after a British withdrawal from the EU.[183] Margallo also threatened to close the border with Gibraltar if Britain left the EU.[184]

The right-wing Dutch populist Geert Wilders said that the Netherlands should follow Britain's example: "Like in 1940s, once again Britain could help liberate Europe from another totalitarian monster, this time called ‘Brussels’."[185]

11 June 2016, Swedish foreign minister Margot Wallstrom said that if Britain left the EU, other countries would have referendums whether to leave the EU, and that if Britain stayed in the EU, other countries would negotiate, ask and demand to have special treatment.[186]

Non-European responses

International Monetary Fund

In February 2016, Christine Lagarde, the managing director of the International Monetary Fund, warned that the uncertainty over the outcome of the referendum would be bad "in and of itself" for the British economy.[187] In response, Leave campaigner Priti Patel said a previous warning from the IMF regarding the coalition government's deficit plan for the UK was proven incorrect and that the IMF "were wrong then and are wrong now".[188]United States

In October 2015, United States Trade Representative Michael Froman declared that the United States was not keen on pursuing a separate free trade agreement (FTA) with Britain if it were to leave the EU, thus undermining, according to The Guardian, a key economic argument of proponents of those who say Britain would prosper on its own and be able to secure bilateral FTAs with trading partners.[189] Also in October 2015, the United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom Matthew Barzun said that UK participation in NATO and the EU made each group "better and stronger" and that, while the decision to remain or leave is a choice for the British people, it was in the US interest that it remain.[190] In April 2016, eight former US Secretaries of the Treasury, who served both Democratic and Republican presidents, urged Britain to remain in the EU.[191]In July 2015, President Barack Obama confirmed the long-standing US preference for the UK to remain in the EU. Obama said: "Having the UK in the EU gives us much greater confidence about the strength of the transatlantic union, and is part of the cornerstone of the institutions built after World War II that has made the world safer and more prosperous. We want to make sure that the United Kingdom continues to have that influence."[192] Obama's intervention was criticised by Republican Senator Ted Cruz as "a slap in the face of British self-determination as the president, typically, elevated an international organisation over the rights of a sovereign people", and stated that "Britain will be at the front of the line for a free trade deal with America", were a Brexit to occur.[193][194]

Prior to the vote, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump anticipated that Britain would leave based on their concerns over migration,[195] Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton hoped that Britain would remain in the EU to strengthen transatlantic co-operation.[196]

Other states

In October 2015, Chinese President Xi Jinping declared his support for Britain remaining in the EU, saying "China hopes to see a prosperous Europe and a united EU, and hopes Britain, as an important member of the EU, can play an even more positive and constructive role in promoting the deepening development of China-EU ties".[197] Chinese diplomats have stated "off the record" that the People's Republic sees the EU as a counterbalance to American economic power, and that an EU without Britain would mean a stronger United States.[197]In February 2016, the finance ministers from the G20 major economies warned that leaving the EU would lead to "a shock" in the global economy.[198][199]

In May 2016, the Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull said that Australia would prefer the UK to remain in the EU, but that it was a matter for the British people, and "whatever judgment they make, the relations between Britain and Australia will be very, very close".[200]

Indonesian president Joko Widodo stated during a European trip that he was not in favour of Brexit.[201]

Sri Lankan Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe issued a statement of reasons why he was "very concerned" at the possibility of Brexit.[202]

Russian President Vladimir Putin said: "I want to say it is none of our business, it is the business of the people of the UK."[203] Maria Zakharova, the official Russian foreign ministry spokesperson, said: "Russia has nothing to do with Brexit. We are not involved in this process in any way. We don’t have any interest in it."[204]

Economists

In November 2015, the Governor of the Bank of England Mark Carney said that the Bank of England would do what was necessary to help the UK economy if the British people voted to leave the EU.[205] In March 2016, Carney told MPs that an EU exit was the "biggest domestic risk" to the UK economy, but that remaining a member also carried risks, related to the European Monetary Union, of which the UK is not a member.[206] In May 2016, Carney said that a "technical recession" was one of the possible risks of the UK leaving the EU.[207] However, Iain Duncan Smith said Carney's comment should be taken with "a pinch of salt", saying "all forecasts in the end are wrong".[208]In December 2015, the Bank of England published a report about the impact of immigration on wages. The report concluded that immigration put downward pressure on workers' wages, particularly low-skilled workers: a 10 percent point rise in the proportion of migrants working in low-skilled services drove down the average wages of low-skilled workers by about 2 percent.[209]

In March 2016, Nobel prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz argued that he might reconsider his support for the UK remaining in the EU if the proposed Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) were to be agreed to.[210] Stiglitz warned that under the investor-state dispute settlement provision in current drafts of the TTIP, governments risked being sued for loss of profits resulting from new regulations, including health and safety regulations to limit the use of asbestos or tobacco.[210]

The German economist Clemens Fuest wrote that at present there is a liberal, free trade bloc in the EU comprising the UK, the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, Sweden, Denmark, Ireland, Slovakia, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania which control 32% of the votes in the European Council and stands in opposition to the dirigiste, protectionist policies favoured by France and its allies.[211] Germany with its "social market" economy stands midway between the French dirigiste economic model and the British free market economic model. From the German viewpoint, the existence of the liberal bloc allows Germany to play-off free market Britain against dirigiste France, and that if Britain were to leave, the liberal bloc would be severely weakened, thereby allowing the French to take the EU into a much more dirigiste direction that would be unattractive from the standpoint of Berlin.[211]

Institute for Fiscal Studies

In May 2016, the Institute for Fiscal Studies said that an EU exit could mean two more years of austerity cuts as the government would have to make up for an estimated loss of £20 billion to £40 billion of tax revenue. The head of the IFS, Paul Johnson said that the UK "could perfectly reasonably decide that we are willing to pay a bit of a price for leaving the EU and regaining some sovereignty and control over immigration and so on. That there would be some price though, I think is now almost beyond doubt."[212]Centre for Economics and Business Research

In June 2016, the Centre for Economics and Business Research warned that 800,000 jobs could be lost if Britain adopted the World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules for trade with Europe, which prominent Brexiteers Boris Johnson, Michael Gove and Nigel Farage said Britain could trade under, if it could not agree a new trade deal with the rest of the EU. WTO rules allow tariffs of 10 per cent on cars, 75 per cent on tobacco and cigars, 22 per cent on fruit and 12 per cent on clothes.[213]Law and economics experts

A study by Oxford Economics for the Law Society of England and Wales has suggested that Brexit would have a particularly large negative impact on the UK financial services industry and the law firms that support it, which could cost the law sector as much as £1.7bn per annum by 2030.[214] The Law Society's own report into the possible effects of Brexit notes that leaving the EU would be likely to reduce the role played by the UK as a centre for resolving disputes between foreign firms, whilst a potential loss of "passporting" rights would require financial services firms to transfer departments responsible for regulatory oversight overseas.[215]World Pensions Forum director M. Nicolas Firzi has argued that the Brexit debate should be viewed within the broader context of economic analysis of EU law and regulation in relation to English common law, arguing: "Every year, the British Parliament is forced to pass tens of new statutes reflecting the latest EU directives coming from Brussels – a highly undemocratic process known as 'transposition'... Slowly but surely, these new laws dictated by EU commissars are conquering English common law, imposing upon UK businesses and citizens an ever-growing collection of fastidious regulations in every field".[216]

A poll of lawyers conducted by a legal recruiter in late May 2016 suggested 57% of lawyers wanted to remain in the EU.[217]

NHS officials

Simon Stevens, head of NHS England, warned in May 2016 that a recession following a Brexit would be "very dangerous" for the health service, saying that "when the British economy sneezes, the NHS catches a cold."[218] Three-quarters of a sample of NHS leaders agreed that leaving the EU would have a negative effect on the NHS as a whole. In particular, eight out of 10 respondents felt that leaving the EU would have a negative impact on trusts' ability to recruit health and social care staff.[219] In April 2016, a group of nearly 200 health professionals and researchers warned that the NHS would be in jeopardy if Britain left the European Union.[220]UK charities

Guidelines by the Charity Commission for England and Wales that forbid political activity for registered charities have kept them silent on the EU poll.[221] According to Simon Wessely, head of psychological medicine at the Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London – neither a special revision of the guidelines from 7 March 2016, nor Cameron's encouragement have made health organisations, most of which support the remain campaign, willing to speak out.[221]Fishing industry

A June 2016 survey of UK fishermen found that 92% intended to vote to leave the EU.[222] The EU's Common Fisheries Policy was mentioned as a central reason for their near-unanimity.[222] More than three-quarters believed that they would be able to land more fish, and 93% stated that leaving the EU would benefit the fishing industry.[223]Historians

In May 2016, more than 300 historians wrote in a joint letter to The Guardian that Britain could play a bigger role in the world as part of the EU. They said: "As historians of Britain and of Europe, we believe that Britain has had in the past, and will have in the future, an irreplaceable role to play in Europe."[224]Exit plan competition

Following David Cameron's announcement of an EU referendum, British think tank the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) announced in July 2013 a competition to find the best plan for a UK exit from the European Union, declaring that a departure is a "real possibility" after the 2015 general election.[225] Iain Mansfield, a Cambridge graduate and UKTI diplomat, submitted the winning thesis: A Blueprint for Britain: Openness not Isolation.[226] Mansfield's submission focused on addressing both trade and regulatory issues with member states as well as other global trading partners.[227][228]Opinion polling

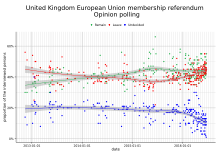

Opinion polling on the referendum

Analysis of polling suggested that young voters tended to support remaining in the EU, whereas those older tend to support leaving, but there was no gender split in attitudes.[233][234] In February 2016 YouGov also found that euroscepticism correlated with people of lower income and that "higher social grades are more clearly in favour of remaining in the EU", but noted that euroscepticism also had strongholds in "the more wealthy, Tory shires".[235] Scotland, Wales and many English urban areas with large student populations were more pro-EU.[235] Big business was broadly behind remaining in the EU, though the situation among smaller companies was less clear cut.[236] In polls of economists, lawyers, and scientists, clear majorities saw the UK's membership of the EU as beneficial.[237][238][239][240][241]

Issues

The number of jobs lost or gained by a withdrawal was a dominant issue; the BBC's outline of issues warned that a precise figure was difficult to find. The Leave campaign argued that a reduction in red tape associated with EU regulations would create more jobs and that small to medium-sized companies who trade domestically would be the biggest beneficiaries. Those arguing to remain in the EU, claimed that millions of jobs would be lost. The EU's importance as a trading partner and the outcome of its trade status if it left was a disputed issue. Whilst those wanting to stay cited that most of the UK's trade was made with the EU, those arguing to leave say that its trade was not as important as it used to be. Scenarios of the economic outlook for the country if it left the EU were generally negative. The United Kingdom also paid more into the EU budget than it received.[242]Citizens of EU countries, including the United Kingdom, have the right to travel, live and work within other EU countries, as free movement is one of the four founding principles of the EU.[243] Campaigners for remaining said that EU immigration had positive impacts on the UK's economy, citing that the country's growth forecasts were partly based upon continued high levels of net immigration.[242] The Office for Budget Responsibility also claimed that taxes from immigrants boost public funding.[242] The Leave campaign believed reduced immigration would ease pressure in public services such as schools and hospitals, as well as giving British workers more jobs and higher wages.[242] According to official Office for National Statistics data, net migration in 2015 was 333,000, which was the second highest level on record, far above David Cameron's target of tens of thousands.[244][245] Net migration from the EU was 184,000.[245] The figures also showed that 77,000 EU migrants who came to Britain were looking for work.[244][245]

After the announcement had been made as to the outcome of the referendum, Rowena Mason, political correspondent for The Guardian offered the following assessment: "Polling suggests discontent with the scale of migration to the UK has been the biggest factor pushing Britons to vote out, with the contest turning into a referendum on whether people are happy to accept free movement in return for free trade."[246] A columnist for The Times, Philip Collins, went a step further in his analysis: "This was a referendum about immigration disguised as a referendum about the European Union."[247]

The Conservative MEP (Member of the European Parliament) representing South East England, Daniel Hannan, predicted on the BBC program Newsnight that the level of immigration would remain high after Brexit.[248] "Frankly, if people watching think that they have voted and there is now going to be zero immigration from the EU, they are going to be disappointed. ... you will look in vain for anything that the Leave campaign said at any point that ever suggested there would ever be any kind of border closure or drawing up of the drawbridge."[249]

The possibility that the UK's smaller constituent countries could vote to remain within the EU but find themselves withdrawn from the EU led to discussion about the risk to the unity of the United Kingdom.[250] Scotland's First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, made it clear that she believed that a second independence referendum would "almost certainly" be demanded by Scots if the UK voted to leave the EU but Scotland did not.[251] The First Minister of Wales, Carwyn Jones, said: "If Wales votes to remain in [the EU] but the UK votes to leave, there will be a... constitutional crisis. The UK cannot possibly continue in its present form if England votes to leave and everyone else votes to stay".[252]

There was concern that the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), a proposed trade agreement between the United States and the EU, would be a threat to the public services of EU member states.[253][254][255][256] Jeremy Corbyn, on the Remain side, said that he pledged to veto TTIP in Government.[257] John Mills, on the Leave side, argued that UK could not veto TTIP because trade pacts were decided by Qualified Majority Voting in the European Council.[258]

There was debate over the extent to which the European Union membership aided security and defence in comparison to the UK's membership of NATO and the United Nations.[259] Security concerns over the union's free movement policy were raised too, because people with EU passports were unlikely to receive detailed checks at border control.[260]

Debates, Q&A sessions and interviews

A debate was held by The Guardian on 15 March 2016, featuring the leader of UKIP Nigel Farage, Conservative MP Andrea Leadsom, the leader of Labour's "yes" campaign Alan Johnson and former leader of the Liberal Democrats Nick Clegg.[261]Earlier in the campaign, on 11 January, a debate took place between Nigel Farage and Carwyn Jones, who was at the time the First Minister of Wales and leader of the Welsh Labour Party.[262][263] Reluctance to have Conservative Party members argue against one another has seen some debates split, with Leave and Remain candidates interviewed separately.[264]

The Spectator held a debate hosted by Andrew Neil on 26 April, which featured Nick Clegg, Liz Kendall and Chuka Umunna arguing for a remain vote, and Nigel Farage, Daniel Hannan and Kate Hoey arguing for a leave vote.[265] The Daily Express held a debate on 3 June, featuring Nigel Farage, Labour MP Kate Hoey and Conservative MP Jacob Rees-Mogg debating Labour MPs Siobhain McDonagh and Chuka Umunna and businessman Richard Reed, co-founder of Innocent drinks.[266] Essex TV produced a documentary named 'Is Essex IN or OUT' released on 20 June, featuring Boris Johnson, local public figures and various members of the public from Essex.[267] Andrew Neil presented four interviews ahead of the referendum. The interviewees were Hilary Benn, George Osborne, Nigel Farage and Iain Duncan Smith on 6, 8, 10 and 17 May, respectively.[268]

The scheduled debates and question sessions included a number of question and answer sessions with various campaigners.[269][270] and a debate on ITV held on 9 June that included Angela Eagle, Amber Rudd and Nicola Sturgeon, Boris Johnson, Andrea Leadsom, and Gisela Stuart.[271]

EU Referendum: The Great Debate was held at Wembley Arena on 21 June and hosted by David Dimbleby, Mishal Husain and Emily Maitlis in front of an audience of 6,000.[272] The audience was split evenly between both sides. Sadiq Khan, Ruth Davidson and Frances O'Grady appeared for Remain. Leave was represented by the same trio as the ITV debate on 9 June (Johnson, Leadsom and Stuart).[273] Europe: The Final Debate with Jeremy Paxman was held the following day on Channel 4.[274]

Voting, voting areas and counts

Result of the referendum by regional voting areas (note that Gibraltar on the Iberian Peninsula is not pictured)

Leave

Remain

Sign outside a polling station in England on the morning of the referendum

In England, as happened in the 2011 AV referendum, the 326 districts were used as the local voting areas and the returns of these then fed into nine English regional counts. In Scotland the local voting areas were the 32 local councils which then fed their results into the Scottish national count, and in Wales the 22 local councils were their local voting areas before the results were then fed into the Welsh national count. Northern Ireland, as was the case in the AV referendum, was a single voting and national count area although local totals by Westminster parliamentary constituency area were announced. Gibraltar was a single voting area and its result was fed into the South West England regional count.[275]

The following table shows the breakdown of the voting areas and regional counts that were used for the referendum.[275]

| Country | Counts and voting areas |

|---|---|

| Referendum declaration; 12 regional counts; 382 voting areas |

| Constituent countries | Counts and voting areas |

|---|---|

| 9 regional counts; 326 voting areas |

|

| Northern Ireland | National count and single voting area; 18 local totals |

| National count; 32 voting areas |

|

| National count; 22 voting areas |

| British Overseas Territory | Voting area |

|---|---|

| Single voting area (regional count: South West England) |

Disturbances

One pro-EU Labour MP, Jo Cox, was shot and killed in Birstall, West Yorkshire the week before the referendum by a man calling himself "death to traitors, freedom for Britain", and a man who intervened was injured.[276] The two rival official campaigns suspended their activities as a mark of respect to Cox.[93] David Cameron cancelled a planned rally in Gibraltar supporting British EU membership.[277] Campaigning resumed on Sunday 19 June.[278][279] Polling officials in the Yorkshire and Humber region also halted counting of the referendum ballots on the evening of 23 June in order to observe a minute of silence.[280] The Conservative Party, Liberal Democrats, UK Independence Party and the Green Party all announced that they would not contest the ensuing by-election in Cox's constituency as a mark of respect;[281]On polling day itself two polling stations in Kingston upon Thames were flooded by rain and had to be relocated.[282] In Winchester, a woman had her name taken by the police after urging voters at a polling station to use her pens instead of the provided pencils, following a conspiracy theory that MI5 were rigging the referendum in favour of remain by erasing and changing votes made with pencil.[283]

Voting results

As announced on Friday 24 June 2016 at 0751 BST by the Chief Counting Officer (CCO) and Chair of the Electoral Commission Jenny Watson at Manchester Town Hall the final result of the referendum was to "Leave the European Union".[284]| United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, 2016 | ||

| Choice | Votes | % |

|---|---|---|

| Leave | 17,410,742 | 51.89 |

| Remain | 16,141,241 | 48.11 |

| Valid votes | 33,551,983 | 99.92 |

| Invalid or blank votes | 25,359 | 0.08 |

| Total votes | 33,577,342 | 100.00 |

| Registered voters and turnout | 46,500,001 | 72.21 |

| Source: Electoral Commission[285] | ||

| Leave: 17,410,742 (51.9%) |

Remain: 16,141,241 (48.1%) |

||

| ▲ | |||

By local district and regional count

| Region | Turnout | Remain votes | Leave votes | Remain % | Leave % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| England (with Gibraltar) | 73.0% | 13,266,996 | 15,188,406 | 46.62% | 53.38% |

| East Midlands | 74.2% | 1,033,036 | 1,475,479 | 41.18% | 58.82% |

| East of England | 75.7% | 1,448,616 | 1,880,367 | 43.52% | 56.48% |

| London | 69.7% | 2,263,519 | 1,513,232 | 59.93% | 40.07% |

| North East England | 69.3% | 562,595 | 778,103 | 41.96% | 58.04% |

| North West England | 70% | 1,699,020 | 1,966,925 | 46.35% | 53.65% |

| South East England | 76.8% | 2,391,718 | 2,567,965 | 48.22% | 51.78% |

| South West England & Gibraltar | 76.7% | 1,503,019 | 1,669,711 | 47.37% | 52.63% |

| West Midlands | 72% | 1,207,175 | 1,755,687 | 40.74% | 59.26% |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 70.7% | 1,158,298 | 1,580,937 | 42.29% | 57.71% |

| Northern Ireland | 62.7% | 440,707 | 349,442 | 55.78% | 44.22% |

| Scotland | 67.2% | 1,661,191 | 1,018,322 | 62.00% | 38.00% |

| Wales | 71.7% | 772,347 | 854,572 | 47.47% | 52.53% |

Reactions to the result

Further information: International reactions to the United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, 2016

Immediate reaction to the vote

Youth protests and non-inclusion of underage voters

The referendum was criticised for not granting people younger than 18 years of age a vote. Unlike in the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, the vote was not extended to 16- and 17-year-old citizens. Critics noted that these people would live with the consequences of the referendum for longer than those who were able to vote. Some supporters for the inclusion of these young voters considered this exclusion a violation of democratic principles and a major shortcoming of the referendum.[286][287] Opinion polls indicated that this group would have voted substantially for Remain.[288][289][290]Increase of applications for passports of other EU countries

The foreign ministry of Ireland stated that the number of application from UK citizens for Irish passports increased significantly after the announcement of the result of the referendum on the membership in the European Union.[291][292] The Irish Embassy in London usually receives 200 passport applications a day, which increased to 4000 a day after the vote to leave.[293] Other EU nations also had increases in requests for passports from British citizens, including France and Belgium.[293]Racist abuse and hate crimes

More than a hundred racist abuse and hate crimes were reported in the immediate aftermath of the referendum with many citing the plan to leave the European Union.[294] On 24 June 2016, a Polish school in Cambridgeshire was vandalised with a sign reading "Leave the EU. No more Polish vermin".[295] Following the referendum result, similar signs were distributed outside homes and schools in Huntingdon, with some left on the cars of Polish residents collecting their children from school.[296] On 26 June, the London office of the Polish Social and Cultural Association was vandalised with racist graffiti.[297] Both incidents were investigated by the police.[295][297] In Wales, a Muslim woman was told to leave after the referendum, even though she had been born and raised in the United Kingdom.[298] Other instances of racism occurred as perceived foreigners were targeted in supermarkets, on buses and on street corners, and told to leave the country immediately.[299]The increase in hate crimes was lamented by Sayeeda Warsi, Baroness Warsi, the former chairwoman of the Conservative Party.[300] Jess Phillips, a Labour MP, vowed to make enquiries in Parliament to determine whether incidents of racial hatred had increased during the weekend after the referendum.[294] British Prime Minister David Cameron condemned the hate crimes as "despicable", adding that they should be stamped out.[301] Meanwhile, Witold Sobków, the Polish Ambassador to the United Kingdom, released a statement saying he was "shocked and deeply concerned by the recent incidents of xenophobic abuse directed against the Polish community and other UK residents of migrant heritage".[301] Sadiq Khan, the Mayor of London, also released a statement condemning those hate crimes.[302] With Anne Hidalgo, the Mayor of Paris, Khan released another statement highlighting the "shared history, shared culture, shared challenges and the shared experience of being one of just a handful of truly global cities."[302] The Board of Deputies of British Jews released a statement, with its chief executive Gillian Merron saying "The Jewish community knows all too well these feelings of vulnerability and will not remain silent in the face of a reported rise in racially motivated harassment."[303] The Muslim Council of Britain also spoke out against the racist incidents that have occurred since the vote to leave the EU.[304] Meanwhile, Cambridgeshire Police encouraged all victims or witnesses of incidents including both written or face-to-face abuse to report it, as either would constitute an offence of creating racial hatred with a maximum sentence of seven years in prison.[296]

Prime Minister David Cameron and Leader of the Opposition Jeremy Corbyn both condemned the attacks in Parliament.[305]

Petition for a new referendum

Within hours of the result's announcement, a petition, calling for a second referendum to be held in the event that a result was secured with less than 60% of the vote and on a turnout of less than 75%, attracted tens of thousands of new signatures. The petition had been initiated by William Oliver Healey of the English Democrats on 24 May 2016, when the Remain faction had been leading in the polls, and had received 22 signatures prior to the referendum result being declared.[306][307][308] On 26 June, Healey made it clear on his Facebook page that the petition had actually been started to favour an exit from the EU and that he was a strong supporter of the Vote Leave and Grassroots Out campaigns. Healey also claimed that the petition had been "hijacked by the remain campaign".[309] English Democrats chairman Robin Tilbrook suggested those who had signed the petition were experiencing "sour grapes" about the result of the referendum.[310]Notification of intention to leave the EU

As with all but one UK referendums[311] it was an advisory referendum and so could theoretically be ignored by Parliament.[312] The most likely way of leaving the EU will be by invoking Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union, which only the departing country can invoke. This will be the first time Article 50 has been invoked[313] When Cameron resigned he stated that the next Prime Minister should activate Article 50 and begin negotiations with the EU.[314] There is dispute over whether the decision to invoke Article 50 is the prerogative of the government, as the government argues, or whether it requires Parliamentary assent[315][316] and the law firm Mishcon de Reya announced that they had been retained by a group of clients to challenge the constitutionality of invoking Article 50 without parliament debating it.[317][318] However, Parliament will be able to vote on any new treaty arrangements that emerge from the withdrawal deal.[319]Political

Political leadership

Prime Minister David Cameron announces his resignation following the outcome of the referendum

Further information: Conservative Party (UK) leadership election, 2016

Theresa May succeeded David Cameron as Prime Minister following the vote

Further information: Labour Party (UK) leadership crisis, 2016

The Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn faced growing criticism from his party, which had supported remaining within the EU, for poor campaigning.[321] It is claimed that there is evidence that Corbyn deliberately sabotaged Labour's campaign to remain part of the EU.[322] In the early hours of Sunday 26 June, Corbyn sacked Hilary Benn

(the shadow foreign secretary) for apparently leading a coup against

him. This led to a string of Labour MPs quickly resigning their roles in

the party.[323][324] A no confidence motion was held on 28 June 2016; Corbyn lost the motion with more than 80% (172) of MPs voting against him.[325]

Corbyn responded with a statement that the motion had no

"constitutional legitimacy" and that he intended to continue as the

elected leader. The vote does not require the party to call a leadership

election[326] but the result is likely to lead to a direct challenge to Corbyn.[327]

Further information: UK Independence Party leadership election, 2016

On 4 July 2016 Nigel Farage

stood down as the leader of UKIP, stating that his "political ambition

has been achieved" following the result of the referendum.[328]Scottish independence

Main article: Proposed second Scottish independence referendum

Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said it was "clear that the

people of Scotland see their future as part of the European Union" and

that Scotland had "spoken decisively" with a "strong, unequivocal" vote

to remain in the European Union.[8] The Scottish Government announced on 24 June 2016 that officials would plan for a "highly likely" second referendum on independence from the United Kingdom and start preparing legislation to that effect.[23] Former First Minister Alex Salmond

said the vote was a "significant and material change" in Scotland's

position within the United Kingdom, and that he was certain his party

would implement its manifesto on holding a second referendum.[329]

Sturgeon said she will communicate to all EU member states that

"Scotland has voted to stay in the EU and I intend to discuss all

options for doing so."[330]Economy

Main article: Aftermath of the United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, 2016 § Economic effects

On the morning of 24 June, the pound sterling fell to its lowest level against the US dollar since 1985,[331] marking the pound down 10% against the US dollar and 7% against the euro. The drop from $1.50 to $1.37 was the biggest move for the currency in any two-hour period in history.[332]The FTSE 100 intially fell 8%, then recovered to be 3% down by the close of trading on 24 June.[333] The FTSE 100 index subsequently rose above its pre-referendum levels.[334]

The referendum result also had an immediate negative economic impact on some other countries. The South African rand experienced its largest single-day decline since 2008, dropping over 8% against the United States dollar.[335][336] Other countries affected include Canada, whose stock exchange fell 1.70%,[337] Nigeria[336] and Kenya.[336]

On 28 June 2016, former governor of Bank of England Mervyn King said that Mark Carney would help to guide Britain through the next few months, adding that BoE would undoubtedly lower the temperature of the post-referendum uncertainty, and that British citizens should keep calm, wait and see.[338]

See also

Notes

- The terms Brexit and Brixit were apparently first coined in June 2012; Brixit was first used by a columnist in The Economist,[not in citation given] while Brexit was first used by a British nationalist group.[specify] The terms were probably inspired by the word Grexit, shorthand for Greek withdrawal from the eurozone. The term Brexit first became a widely used buzzword in 2013.[13]

References

The referendum result is not legally binding - Parliament still has to pass the laws that will get Britain out of the 28 nation bloc, starting with the repeal of the 1972 European Communities Act.

- King Says Carney Calm Will Guide U.K. Through Brexit Uncertainty J. Ward, Bloomberg, 28 Jun 2016

Further reading

- George, Stephen (January 2000). "Britain: anatomy of a Eurosceptic state". Journal of European Integration (Taylor and Francis) 22 (1): 15–33. doi:10.1080/07036330008429077.

- Usherwood, Simon (March 2007). "Proximate factors in the mobilization of anti‐EU groups in France and the UK: the European Union as first‐order politics". Journal of European Integration (Taylor and Francis) 29 (1): 3–21. doi:10.1080/07036330601144177.

- Emerson, Michael (April 2016). "The Economics of a Brexit". Intereconomics (Springer Science+Business Media) 51 (2): 46–47. doi:10.1007/s10272-016-0574-2.

External links

|

Find more about

United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, 2016 at Wikipedia's sister projects |

|

| Media from Commons | |

| News from Wikinews | |

| Data from Wikidata | |

|

||

|

||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||

The French president and Spanish prime minister have both said they are opposed to the EU negotiating potential membership for Scotland.

FTSE 100 surrenders £85bn in two days, pound slides and banking stocks plunge in Brexit aftermath

In an ironic twist, it emerged Sunday that the petition's creator was in fact in favor of so-called Brexit. In a message posted to Facebook, William Oliver Healey sought to distance himself from the petition, saying it had been hijacked by those in favor of remaining in the EU.

the confidence vote does not automatically trigger a leadership election and Corbyn, who says he enjoys strong grassroots support, refused to quit. 'I was democratically elected leader of our party for a new kind of politics by 60 percent of Labour members and supporters, and I will not betray them by resigning,' he said.

No comments:

Post a Comment