I was just walking in the pine, oak and redwood forests near where I live (less than one mile) and I saw hundreds of these mushrooms growing everywhere usually near pine trees where they are somewhat symbiotic with here in North America. I try to tell people about them because they are very colorful and often if people eat them first their mind dies and then their livers die and then they die.

So, unless you really know what you are doing like some in Europe you will be dead dead dead within 24 hours of touching with your fingers or ingesting these things. So,watch out.

I see many people collecting mostly other edible mushrooms in the forests now. I'm not one of these unless I am in Mt. Shasta where there are Morels which are my favorite edible mushroom on earth. A friend know where to get these in season and they are wonderful. But, Mostly Amanitas are fairly sure death except for a few experts in Europe and the U.S. So, be careful.

The only animal or creature that can survive eating them in place that I know of is the Banana Slug which is also the Mascot of UCSC here in northern California.

begin quote from:

Amanita muscaria - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amanita_muscaria

Amanita muscaria

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Amanita muscaria | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Showing three stages as the mushroom expands | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Phylum: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Agaricales |

| Family: | Amanitaceae |

| Genus: | Amanita |

| Species: | A. muscaria |

| Binomial name | |

| Amanita muscaria (L.) Lam. (1783) |

|

| Amanita muscaria | |

|---|---|

| Mycological characteristics | |

| gills on hymenium | |

|

cap is flat or convex |

|

| hymenium is free | |

| stipe has a ring and volva | |

| spore print is white | |

| ecology is mycorrhizal | |

|

edibility: poisonous or psychoactive |

|

This iconic toadstool is a large white-gilled, white-spotted, usually red mushroom, and is one of the most recognisable and widely encountered in popular culture. Several subspecies with differing cap colour have been recognised, including the brown regalis (often considered a separate species), the yellow-orange flavivolvata, guessowii, formosa, and the pinkish persicina. Genetic studies published in 2006 and 2008 show several sharply delineated clades that may represent separate species.

Although classified as poisonous, reports of human deaths resulting from its ingestion are extremely rare. After parboiling—which weakens its toxicity and breaks down the mushroom's psychoactive substances—it is eaten in parts of Europe, Asia, and North America. Amanita muscaria is noted for its hallucinogenic properties, with its main psychoactive constituent being the compound muscimol. The mushroom was used as an intoxicant and entheogen by the peoples of Siberia, and has a religious significance in these cultures. There has been much speculation on possible traditional use of this mushroom as an intoxicant in other places such as the Middle East, Eurasia, North America, and Scandinavia.

Contents

Taxonomy and naming

The name of the mushroom in many European languages is thought to be derived from its use as an insecticide when sprinkled in milk. This practice has been recorded from Germanic- and Slavic-speaking parts of Europe, as well as the Vosges region and pockets elsewhere in France, and Romania.[1] Albertus Magnus was the first to record it in his work De vegetabilibus some time before 1256,[2] commenting vocatur fungus muscarum, eo quod in lacte pulverizatus interficit muscas, "it is called the fly mushroom because it is powdered in milk to kill flies."[3]

Showing the partial veil under the cap dropping away to form a ring around the stipe

The English mycologist John Ramsbottom reported that Amanita muscaria was used for getting rid of bugs in England and Sweden, and bug agaric was an old alternate name for the species.[3] French mycologist Pierre Bulliard reported having tried without success to replicate its fly-killing properties in his work Histoire des plantes vénéneuses et suspectes de la France (1784), and proposed a new binomial name Agaricus pseudo-aurantiacus because of this.[9] One compound isolated from the fungus is 1,3-diolein ( 1,3-Di(cis-9-octadecenoyl)glycerol), which attracts insects.[10] It has been hypothesised that the flies intentionally seek out the fly agaric for its intoxicating properties.[11] An alternative derivation proposes that the term fly- refers not to insects as such but rather the delirium resulting from consumption of the fungus. This is based on the medieval belief that flies could enter a person's head and cause mental illness.[12] Several regional names appear to be linked with this connotation, meaning the "mad" or "fool's" version of the highly regarded edible mushroom Amanita caesarea. Hence there is oriol foll "mad oriol" in Catalan, mujolo folo from Toulouse, concourlo fouolo from the Aveyron department in Southern France, ovolo matto from Trentino in Italy. A local dialect name in Fribourg in Switzerland is tsapi de diablhou, which translates as "Devil's hat".[13]

Classification

Amanita muscaria is the type species of the genus. By extension, it is also the type species of Amanita subgenus Amanita, as well as section Amanita within this subgenus. Amanita subgenus Amanita includes all Amanita with inamyloid spores. Amanita section Amanita includes the species which have very patchy universal veil remnants, including a volva that is reduced to a series of concentric rings and the veil remnants on the cap to a series of patches or warts. Most species in this group also have a bulbous base.[14][15] Amanita section Amanita consists of A. muscaria and its close relatives, including A. pantherina (the panther cap), A. gemmata, A. farinosa, and A. xanthocephala.[16] Modern fungal taxonomists have classified Amanita muscaria and its allies this way based on gross morphology and spore inamyloidy. Two recent molecular phylogenetic studies have confirmed this classification as natural.[17][18]Amanita muscaria varies considerably in its morphology, and many authorities recognise several subspecies or varieties within the species. In The Agaricales in Modern Taxonomy, German mycologist Rolf Singer listed three subspecies, though without description: A. muscaria ssp. muscaria, A. muscaria ssp. americana, and A. muscaria ssp. flavivolvata.[14]

Contemporary authorities recognise up to seven varieties:

| Image | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

|

Amanita muscaria var. muscaria | the typical red-and-white spotted variety. Some authorities, such as Rodham Tulloss, only use this name for Eurasian and western Alaskan populations.[15][19] |

|

Amanita muscaria var. flavivolvata | red, with yellow to yellowish-white warts. It is found from southern Alaska down through the Rocky Mountains, through Central America, all the way to Andean Colombia. Rodham Tulloss uses this name to describe all "typical" A. muscaria from indigenous New World populations.[15][20] |

|

Amanita muscaria var. alba | an uncommon fungus, has a white to a silvery white cap that has white warts but is similar to the usual form of mushroom.[15][21] |

|

Amanita muscaria var. formosa | has a yellow to orange-yellow cap with yellowish warts and stem (which may be tan). Some authorities (cf. Jenkins) use the name for all A. muscaria which fit this description worldwide, others (cf. Tulloss) restrict its use to Eurasian populations.[15][22] |

|

Amanita muscaria var. guessowii | has a yellow to orange cap, with the centre more orange or perhaps even reddish orange. It is found most commonly in northeastern North America, from Newfoundland and Quebec south all the way to the state of Tennessee. Some authorities (cf. Jenkins) treat these populations as A. muscaria var. formosa, while others (cf. Tulloss) recognise them as a distinct variety.[15][22] |

|

Amanita muscaria var. persicina | pinkish to orangish, sometimes called "melon"-coloured, with poorly formed, or at times absent remnants of universal veil on the stem and vassal bulb; it is known from the southeastern coastal areas of the United States, and was described in 1977.[15][23] Recent DNA sequencing suggests this may be a separate species which may require naming. |

|

Amanita muscaria var. regalis | from Scandinavia and Alaska.[24] is liver-brown and has yellow warts. It appears to be distinctive, and some authorities (cf. Tulloss) treat it as a separate species, while others (cf. Jenkins) treat it as a variety of the A. muscaria.[15][25] |

Description

Cross section of fruiting body, showing pigment under skin and free gills

The free gills are white, as is the spore print. The oval spores measure 9–13 by 6.5–9 μm; they do not turn blue with the application of iodine.[32] The stipe is white, 5–20 cm high (2–8 in) by 1–2 cm (0.4–0.8 in) wide, and has the slightly brittle, fibrous texture typical of many large mushrooms. At the base is a bulb that bears universal veil remnants in the form of two to four distinct rings or ruffs. Between the basal universal veil remnants and gills are remnants of the partial veil (which covers the gills during development) in the form of a white ring. It can be quite wide and flaccid with age. There is generally no associated smell other than a mild earthiness.[33][34]

Although very distinctive in appearance, the fly agaric has been mistaken for other yellow to red mushroom species in the Americas, such as Armillaria cf. mellea and the edible Amanita basii—a Mexican species similar to A. caesarea of Europe. Poison control centres in the U.S. and Canada have become aware that amarill (Spanish for 'yellow') is a common name for the A. caesarea-like species in Mexico.[22] Amanita caesarea can be distinguished by its entirely orange to red cap which lacks the numerous white warty spots of the fly agaric. Furthermore, the stem, gills and ring of A. caesarea are bright yellow, not white.[35] The volva is a distinct white bag, not broken into scales.[36] In Australia, the introduced fly agaric may be confused with the native vermilion grisette (Amanita xanthocephala), which grows in association with eucalypts. The latter species generally lacks the white warts of A. muscaria and bears no ring.[37]

Distribution and habitat

Amanita muscaria var. formosa sensu Thiers, southern Oregon Coast

Ectomycorrhizal, Amanita muscaria forms symbiotic relationships with many trees, including pine, spruce, fir, birch, and cedar. Commonly seen under introduced trees,[43] A. muscaria is the fungal equivalent of a weed in New Zealand, Tasmania and Victoria, forming new associations with southern beech (Nothofagus).[44] The species is also invading a rainforest in Australia, where it may be displacing the native species.[43] It appears to be spreading northwards, with recent reports placing it near Port Macquarie on the New South Wales north coast.[45] It was recorded under silver birch (Betula pendula) in Manjimup, Western Australia in 2010.[46] Although it has apparently not spread to eucalypts in Australia, it has been recorded associating with them in Portugal.[47]

Toxicity

Mature. The white spots may wash off with heavy rainfall

Amanita muscaria contains several biologically active agents, at least one of which, muscimol, is known to be psychoactive. Ibotenic acid, a neurotoxin, serves as a prodrug to muscimol, with approximately 10–20% converting to muscimol after ingestion. An active dose in adults is approximately 6 mg muscimol or 30 to 60 mg ibotenic acid;[52][53] this is typically about the amount found in one cap of Amanita muscaria.[54] The amount and ratio of chemical compounds per mushroom varies widely from region to region and season to season, which can further confuse the issue. Spring and summer mushrooms have been reported to contain up to 10 times more ibotenic acid and muscimol than autumn fruitings.[48]

A fatal dose has been calculated as 15 caps.[55] Deaths from this fungus A. muscaria have been reported in historical journal articles and newspaper reports,[56][57][58] but with modern medical treatment, fatal poisoning from ingesting this mushroom is extremely rare.[59] Many older books list Amanita muscaria as "deadly", but this is an error that implies the mushroom is more toxic than it is.[60] The North American Mycological Association has stated there were no reliably documented fatalities from eating this mushroom during the 20th century.[61] The vast majority (90% or more) of mushroom poisoning deaths are from eating the greenish to yellowish "death cap", (A. phalloides) or perhaps even one of the several white Amanita species which are known as destroying angels.[62]

The active constituents of this species are water-soluble, and boiling and then discarding the cooking water at least partly detoxifies A. muscaria.[63] Drying may increase potency, as the process facilitates the conversion of ibotenic acid to the more potent muscimol.[64] According to some sources, once detoxified, the mushroom becomes edible.[65][66]

Pharmacology

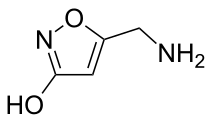

Muscimol, the principal psychoactive constituent of A. muscaria

Ibotenic acid, a prodrug to muscimol found in A. muscaria

The major toxins involved in A. muscaria poisoning are muscimol (3-hydroxy-5-aminomethyl-1-isoxazole, an unsaturated cyclic hydroxamic acid) and the related amino acid ibotenic acid. Muscimol is the product of the decarboxylation (usually by drying) of ibotenic acid. Muscimol and ibotenic acid were discovered in the mid-20th century.[70][71] Researchers in England,[72] Japan,[73] and Switzerland[71] showed that the effects produced were due mainly to ibotenic acid and muscimol, not muscarine.[10][70] These toxins are not distributed uniformly in the mushroom. Most are detected in the cap of the fruit, a moderate amount in the base, with the smallest amount in the stalk.[74][75] Quite rapidly, between 20 and 90 minutes after ingestion, a substantial fraction of ibotenic acid is excreted unmetabolised in the urine of the consumer. Almost no muscimol is excreted when pure ibotenic acid is eaten, but muscimol is detectable in the urine after eating A. muscaria, which contains both ibotenic acid and muscimol.[53]

Ibotenic acid and muscimol are structurally related to each other and to two major neurotransmitters of the central nervous system: glutamic acid and GABA respectively. Ibotenic acid and muscimol act like these neurotransmitters, muscimol being a potent GABAA agonist, while ibotenic acid is an agonist of NMDA glutamate receptors and certain metabotropic glutamate receptors[76] which are involved in the control of neuronal activity. It is these interactions which are thought to cause the psychoactive effects found in intoxication. Muscimol is the agent responsible for the majority of the psychoactivity.[12][54]

Muscazone is another compound that has more recently been isolated from European specimens of the fly agaric. It is a product of the breakdown of ibotenic acid by ultra-violet radiation.[77] Muscazone is of minor pharmacological activity compared with the other agents.[12] Amanita muscaria and related species are known as effective bioaccumulators of vanadium; some species concentrate vanadium to levels of up to 400 times those typically found in plants.[78] Vanadium is present in fruit-bodies as an organometallic compound called amavadine.[78] The biological importance of the accumulation process is unknown.[79]

Symptoms

Fly agarics are known for the unpredictability of their effects. Depending on habitat and the amount ingested per body weight, effects can range from nausea and twitching to drowsiness, cholinergic crisis-like effects (low blood pressure, sweating and salivation), auditory and visual distortions, mood changes, euphoria, relaxation, ataxia, and loss of equilibrium.[48][49][54][57]In cases of serious poisoning the mushroom causes delirium, somewhat similar in effect to anticholinergic poisoning (such as that caused by Datura stramonium), characterised by bouts of marked agitation with confusion, hallucinations, and irritability followed by periods of central nervous system depression. Seizures and coma may also occur in severe poisonings.[49][54] Symptoms typically appear after around 30 to 90 minutes and peak within three hours, but certain effects can last for several days.[51][53] In the majority of cases recovery is complete within 12 to 24 hours.[63] The effect is highly variable between individuals, with similar doses potentially causing quite different reactions.[48][53][80] Some people suffering intoxication have exhibited headaches up to ten hours afterwards.[53] Retrograde amnesia and somnolence can result following recovery.[54]

Treatment

Medical attention should be sought in cases of suspected poisoning. If the delay between ingestion and treatment is less than four hours, activated charcoal is given. Gastric lavage can be considered if the patient presents within one hour of ingestion.[81] Inducing vomiting with syrup of ipecac is no longer recommended in any poisoning situations.[82]There is no antidote, and supportive care is the mainstay of further treatment for intoxication. Though sometimes referred to as a deliriant and while muscarine was first isolated from A. muscaria and as such is its namesake, muscimol does not have action, either as an agonist or antagonist, at the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor site, and therefore atropine or physostigmine as an antidote is not recommended.[83] If a patient is delirious or agitated, this can usually be treated by reassurance and, if necessary, physical restraints. A benzodiazepine such as diazepam or lorazepam can be used to control combativeness, agitation, muscular overactivity, and seizures.[48] Only small doses should be used, as they may worsen the respiratory depressant effects of muscimol.[84] Recurrent vomiting is rare, but if present may lead to fluid and electrolyte imbalances; intravenous rehydration or electrolyte replacement may be required.[54][85] Serious cases may develop loss of consciousness or coma, and may need intubation and artificial ventilation.[49][86] Hemodialysis can remove the toxins, although this intervention is generally considered unnecessary.[63] With modern medical treatment the prognosis is typically good following supportive treatment.[59][63]

Psychoactive use

The wide range of psychedelic effects can be variously described as depressant, sedative-hypnotic, dissociative, and deliriant; paradoxical effects may occur. Perceptual phenomena such as macropsia and micropsia may occur, which may have been the inspiration for the effect of mushroom-consumption in Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland,[87] although "no evidence has ever been found that linked Carroll to recreational drug use".[88] Additionally, A. muscaria cannot be commercially cultivated, due to its mycorrhizal relationship with the roots of pine trees. However, following the outlawing of psilocybin mushrooms in the United Kingdom in 2006, the sale of the still legal A. muscaria began increasing.[89]Professor Marija Gimbutas, a renowned Lithuanian historian, reported to R. Gordon Wasson on the use of this mushroom in Lithuania. In remote areas of Lithuania Amanita muscaria has been consumed at wedding feasts, in which mushrooms were mixed with vodka. The professor also reported that the Lithuanians used to export A. muscaria to the Lapps in the Far North for use in shamanic rituals. The Lithuanian festivities are the only report that Wasson received of ingestion of fly agaric for religious use in Eastern Europe.[90]

Siberia

Amanita muscaria was widely used as an entheogen by many of the indigenous peoples of Siberia. Its use was known among almost all of the Uralic-speaking peoples of western Siberia and the Paleosiberian-speaking peoples of the Russian Far East. There are only isolated reports of A. muscaria use among the Tungusic and Turkic peoples of central Siberia and it is believed that on the whole entheogenic use of A. muscaria was not practised by these peoples.[91] In western Siberia, the use of A. muscaria was restricted to shamans, who used it as an alternative method of achieving a trance state. (Normally, Siberian shamans achieve trance by prolonged drumming and dancing.) In eastern Siberia, A. muscaria was used by both shamans and laypeople alike, and was used recreationally as well as religiously.[91] In eastern Siberia, the shaman would take the mushrooms, and others would drink his urine.[92] This urine, still containing psychoactive elements, may be more potent than the A. muscaria mushrooms with fewer negative effects such as sweating and twitching, suggesting that the initial user may act as a screening filter for other components in the mushroom.[93]The Koryak of eastern Siberia have a story about the fly agaric (wapaq) which enabled Big Raven to carry a whale to its home. In the story, the deity Vahiyinin ("Existence") spat onto earth, and his spittle became the wapaq, and his saliva becomes the warts. After experiencing the power of the wapaq, Raven was so exhilarated that he told it to grow forever on earth so his children, the people, could learn from it.[94] Among the Koryaks, one report said that the poor would consume the urine of the wealthy, who could afford to buy the mushrooms.[95]

Other reports of use

The Finnish historian T. I. Itkonen mentions that A. muscaria was once used among the Sami people: sorcerers in Inari would consume fly agarics with seven spots.[96] In 1979, Said Gholam Mochtar and Hartmut Geerken published an article in which they claim to have discovered a tradition of medicinal and recreational use of this mushroom among a Parachi-speaking group in Afghanistan.[97] There are also unconfirmed reports of religious use of A. muscaria among two Subarctic Native American tribes. Ojibwa ethnobotanist Keewaydinoquay Peschel reported its use among her people, where it was known as the miskwedo.[98][99] This information was enthusiastically received by Wasson, although evidence from other sources was lacking.[100] There is also one account of a Euro-American who claims to have been initiated into traditional Tlicho use of Amanita muscaria.[101]Vikings

The notion that Vikings used A. muscaria to produce their berserker rages was first suggested by the Swedish professor Samuel Ödmann in 1784.[102] Ödmann based his theories on reports about the use of fly agaric among Siberian shamans. The notion has become widespread since the 19th century, but no contemporary sources mention this use or anything similar in their description of berserkers. Muscimol is generally a mild relaxant, but it can create a range of different reactions within a group of people.[103] It is possible that it could make a person angry, or cause them to be "very jolly or sad, jump about, dance, sing or give way to great fright".[103]Fly trap

Amanita muscaria is traditionally used for catching flies possibly due to its content of ibotenic acid and muscimol. Recently, an analysis of nine different methods for preparing A. muscaria for catching flies in Slovenia have shown that the release of ibotenic acid and muscimol did not depend on the solvent (milk or water) and that thermal and mechanical processing led to faster extraction of ibotenic acid and muscimol.[104]In Religion

Soma

See also: Botanical identity of Soma-Haoma

In 1968, R. Gordon Wasson proposed that A. muscaria was the Soma talked about in the Rig Veda of India,[105] a claim which received widespread publicity and popular support at the time.[106] He noted that descriptions of Soma omitted any description of roots, stems or seeds, which suggested a mushroom,[107] and used the adjective hári "dazzling" or "flaming" which the author interprets as meaning red.[108] One line described men urinating Soma;

this recalled the practice of recycling urine in Siberia. Soma is

mentioned as coming "from the mountains", which Wasson interpreted as

the mushroom having been brought in with the Aryan invaders from the

north.[109]

Indian scholars Santosh Kumar Dash and Sachinanda Padhy pointed out

that both eating of mushrooms and drinking of urine were proscribed,

using as a source the Manusmṛti.[110]

In 1971, Vedic scholar John Brough from Cambridge University rejected

Wasson's theory and noted that the language was too vague to determine a

description of Soma.[111] In his 1976 survey, Hallucinogens and Culture,

anthropologist Peter T. Furst evaluated the evidence for and against

the identification of the fly agaric mushroom as the Vedic Soma,

concluding cautiously in its favour.[112]Christianity

Culinary use

The toxins in A. muscaria are water-soluble. When sliced thinly, or finely diced and boiled in plentiful water until thoroughly cooked, it seems to be detoxified.[65] Although its consumption as a food has never been widespread,[117] the consumption of detoxified A. muscaria has been practiced in some parts of Europe (notably by Russian settlers in Siberia) since at least the 19th century, and likely earlier. The German physician and naturalist Georg Heinrich von Langsdorff wrote the earliest published account on how to detoxify this mushroom in 1823. In the late 19th century, the French physician Félix Archimède Pouchet was a populariser and advocate of A. muscaria consumption, comparing it to manioc, an important food source in tropical South America that must be detoxified before consumption.[65]Use of this mushroom as a food source also seems to have existed in North America. A classic description of this use of A. muscaria by an African-American mushroom seller in Washington, D.C., in the late 19th century is described by American botanist Frederick Vernon Coville. In this case, the mushroom, after parboiling, and soaking in vinegar, is made into a mushroom sauce for steak.[118] It is also consumed as a food in parts of Japan. The most well-known current use as an edible mushroom is in Nagano Prefecture, Japan. There, it is primarily salted and pickled.[119]

A 2008 paper by food historian William Rubel and mycologist David Arora gives a history of consumption of A. muscaria as a food and describes detoxification methods. They advocate that Amanita muscaria be described in field guides as an edible mushroom, though accompanied by a description on how to detoxify it. The authors state that the widespread descriptions in field guides of this mushroom as poisonous is a reflection of cultural bias, as several other popular edible species, notably morels, are toxic unless properly cooked.[65]

Legal Status

Australia

Photographed in Mount Lofty Botanic Gardens, Adelaide Hills, South Australia

The Netherlands

Amanita muscaria and Amanita pantherina are illegal to buy, sell, or possess since December 2008. Possession of amounts larger than 0.5 g dried or 5 g fresh lead to a criminal charge.[121]United Kingdom

It is illegal to produce, supply, or import this drug under the Psychoactive Substance Act, which came into effect on May 26, 2016.[122]Cultural depictions

Literature

Jose de Creeft's sculpture Alice in Wonderland in Eastern Central Park,

New York. Alice sits on a mushroom, inviting children to climb up and

join her. The mushroom in the sculpture is not a faithfully reproduced Amanita muscaria; the reference within Lewis Carroll's original literary work upon which the sculpture is based is often discussed.[129][130]

See also

References

- Letcher, p 129.

Further reading

- Allegro, John (2009). The sacred mushroom and the cross (40th anniversary ed.). Crestline, CA: Gnostic Media. ISBN 978-0-9825562-7-6.

- Arora, David (1986). Mushrooms demystified: a comprehensive guide to the fleshy fungi (2nd ed.). Berkeley: Ten Speed Press. ISBN 0-89815-169-4.

- Benjamin, Denis R. (1995). Mushrooms: poisons and panaceas—a handbook for naturalists, mycologists and physicians. New York: WH Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-2600-9.

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2006). Hallucinogenic mushrooms: an emerging trend case study (PDF). EMCDDA Thematic Papers. Lisbon, Portugal: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. ISBN 92-9168-249-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-13.

- Letcher, Andy (2006). Shroom: A Cultural history of the magic mushroom. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-22770-8.

- Ramsbottom, J. (1953). Mushrooms & Toadstools. Collins. ISBN 1-870630-09-2.

- Wasson, R. Gordon (1968). Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality. Harcourt Brace Jovanovick. ISBN 0-88316-517-1.

- Wasson, R. Gordon (1980). The Wondrous Mushroom: Mycolatry in Mesoamerica. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-068443-X.

- Furst, Peter T. (1976). Hallucinogens and Culture. Chandler & Sharp. pp. 98–106. ISBN 0-88316-517-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amanita muscaria. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Amanita muscaria |

- Webpages on Amanita species by Tulloss and Yang Zhuliang

- Magic Mushrooms and Reindeer - Weird Nature. A short video on the use of Amanita muscaria mushrooms by the Sami people and their reindeer produced by the BBC. [1]

- Amanita on erowid.org

No comments:

Post a Comment