begin quote from:

L.A. County seeing more fatalities from Omicron as COVID-19 deaths climb

Deaths from COVID-19 in Los Angeles County have soared over the last week, with officials saying most of the recent fatalities appear to be from the Omicron variant.

The spread of the latest coronavirus variant has moved with unprecedented speed since December, although officials have said people who get infected with Omicron generally get less severe symptoms than with the earlier Delta variant. Even so, officials say it is fatal for some.

Of 102 deaths reported Thursday — the highest single-day tally since March 10 — 90% involved people who became ill with COVID-19 after Christmas, and 80% were among those who fell ill after New Year’s Day, indicating a high likelihood of Omicron infection, Los Angeles County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said.

It appears that people who are dying from the Omicron variant are deteriorating much more quickly than those infected by earlier variants, Ferrer told reporters.

“It means that for the people who are, in fact, ending up passing away from COVID, if they were infected with Omicron, it looks like they get hit pretty hard earlier on,” Ferrer said.

During the summer Delta wave, COVID-19 patients were diagnosed with a coronavirus infection or started having symptoms four to five weeks before their deaths. But among fatalities reported late last week, many had an initial onset of symptoms or first diagnosis three weeks or earlier before their deaths.

“That’s a relatively short period of time between the time somebody gets infected, gets their symptoms and then passes away,” Ferrer said.

Over the seven-day period that ended Sunday, L.A. County is averaging 61 COVID-19 deaths a day, according to a Times analysis of state data released Monday. That surpasses the spring 2020 surge at the start of the pandemic, which maxed out at 50 deaths a day; the first summer surge, at 49 deaths a day; and last summer’s Delta surge, which topped out at 35.

But last winter’s surge was significantly worse: About 240 deaths a day were reported in L.A. County.

Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti said he believes “we’re in a better place” compared with last winter, given the overall lesser severity of Omicron, even though it is more widespread.

But the rising death toll can’t be ignored or dismissed, officials say.

“We’re still walking through … the shadow of the valley of death right now when we see 100-plus people in my city, my county, die in a single day like we did last week,” Garcetti said. “And somehow that’s become normalized, or we don’t think about it as hard as we used to. I do. I still think about it. I pray on it each night. I pray on it in the morning when I wake up.”

There also are growing signs that new Omicron cases have peaked in California. But officials expect hospitals to be challenged for days and weeks to come and deaths from the winter surge to continue.

“The fact that Omicron is so infectious has created a bigger problem” than other characteristics of the variant itself, said Dr. Armand Dorian, chief executive officer of USC Verdugo Hills Hospital in Glendale.

“The virus itself is not as lethal as Delta. Not as many people who get it will be critically ill or go into the ICU. But more people are getting infected — I mean tremendously more people,” Dorian said.

That means that even if a smaller percentage of people who are infected end up with dire illness, the huge numbers of cases have resulted in high numbers of deaths.

The rampant infectiousness of the Omicron variant has also pulled away more healthcare workers who get sick, creating staffing woes for hospitals and other health facilities.

“How do we discharge you to a nursing home or a skilled nursing facility? Because their staff is short. It’s a chain. It’s one big loop. And if one of the links is broken, everything backs up,” Dorian said.

Dorian said that a few weeks ago, roughly 10% of staff at USC Verdugo Hills were out. As workers have recovered, that number has fallen to around 3%, he said.

The crunch has been felt especially hard in emergency departments: During earlier surges, “people really didn’t utilize the ER unless they were really sick” and people with illnesses besides COVID weren’t coming in either, Dorian said. “Now they are.”

More than a third of patients in the Glendale hospital are positive for the coronavirus, although some are “incidental” patients who came to the hospital for something different and were tested and found to have the virus when they arrived, Dorian said.

He estimated that 70% of their coronavirus-positive patients “are here because of COVID — and for everybody who has COVID, it is a complicating factor.”

There are some estimates that 80% to 90% of Omicron infections result in no symptoms, but the unprecedented wave of cases linked to the new variant could still result in record hospital admissions in some countries, Dr. Christopher Murray, the director of the University of Washington’s Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation, said in a commentary for the journal The Lancet.

That’s already the case nationwide. Across the country, the U.S. in recent days tallied about 145,000 coronavirus-positive people in hospitals. That’s more than the previous pandemic high of 124,000 recorded last winter.

Across the U.S., average daily COVID-19 deaths this winter have exceeded that of the summer Delta wave. The nation was averaging nearly 2,000 deaths a day in recent days, exceeding the summer high of about 1,900 daily deaths. The latest figure is still lower than the record 3,400 deaths a day last winter.

“As cases and hospitalizations remain high, of most concern is the increase in deaths,” the L.A. County Department of Public Health said in a statement. Unvaccinated people in L.A. County were 23 times more likely to die from COVID-19 compared with those who are fully vaccinated, recent data show.

“Since the beginning of the pandemic, we have recognized that while many experience mild illness from COVID, there are others that will not do well if they become infected,” Ferrer said in a statement Friday.

The number of coronavirus-positive patients in L.A. County’s intensive care units continues to rise. As of Sunday, there were 794 coronavirus-positive ICU patients in L.A. County, up 28% from the previous week. The latest figure is the highest number in nearly a year, but still less than half the record high of 1,731 on Jan. 8, 2021.

The number of coronavirus-positive hospitalized patients has started to stabilize. Over the last week, L.A. County reported between 4,500 and 4,800 patients, figures that stopped significantly climbing late last week.

And new daily coronavirus cases appear to be declining. By Sunday, L.A. County was averaging about 31,000 cases a day over the past week, according to state data released Monday; more than a week ago, it was averaging 40,000 to 44,000 cases a day, a record high.

Still, case rates are not dropping evenly. Wastewater analysis indicates that while downtown and Westside areas show slightly lower levels of the coronavirus, viral levels in the eastern and southern parts of the county are still high, Ferrer said.

The wastewater data correlate with areas now reporting the highest rates of coronavirus cases, including in South L.A., southeast L.A. County, East L.A., the northeastern San Fernando Valley and parts of the San Gabriel Valley. That’s a shift from December, when the county’s highest case rates were in wealthier communities along the Malibu coast, the Westside, the southern San Fernando Valley and the Hollywood Hills communities.

At that time, “those most likely to become infected often were travelers, those attending entertainment venues and those intermingling in places where many were close together while unmasked,” Ferrer said. “Some of the recent shifts associated with widespread community transmission likely reflect the fact that we’re now seeing increased transmission among those whose jobs are putting them in close contact with others and who often live in crowded housing.”

Coronavirus case rates are higher among Latino and Black residents compared with white residents. For every 100,000 Latino residents, there were about 3,600 cases reported over a two-week period, and for every 100,000 Black residents, there were 2,700 cases. For every 100,000 Asian American residents, there were 2,300, and for every 100,000 white residents, there were 2,100.

Vaccination rates among L.A. County’s Latino and Black residents remain lower than other racial and ethnic groups. For those 5 and older, 58% of Black and 64% of Latino residents have received at least one dose; 77% of white, 82% of Native American and 87% of Asian American residents have received one.

Health officials have expressed concern about low vaccination rates among children 5 to 11. Only 29% of children in that age group in L.A. County have received at least one dose. By comparison, in San Francisco, 71% of children in that age group have received at least one dose of vaccine.

“It creates significant vulnerability for increased spread, not just among children, but among all of us,” Ferrer said.

With coronavirus transmission rates still extraordinarily high, health experts and officials are still urging people to do all they can to avoid getting infected: Wear masks in indoor public settings and avoid nonessential gatherings, especially indoors and in places where masks are not worn, such as in restaurants and bars.

In a study published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology Letters, Yale University researchers recently found that restaurant servers were exposed most frequently to airborne coronavirus particles compared with other workers in high-risk settings, according to a report summarizing the results of a study using mobile viral detectors clipped on their shirt collar for five days that accumulated virus-laden aerosols and droplets.

Of the 62 clips that were returned to researchers, five collected coronavirus. Four of them were worn by restaurant servers; and one by a homeless shelter staff member. Two of the sensors by restaurant waiters had exceptionally high viral load, “suggestive of close contact with one or more infected individuals,” the report said.

None of the clips worn by healthcare workers collected coronavirus, which researchers expected because of hospitals’ strict infection control requirements. The clips were in circulation in Connecticut in the first half of 2021.

Officials are urging people to get up-to-date on COVID-19 vaccinations and booster shots. While 3 million L.A. County residents 12 and older have received their booster shot, an additional 3 million are eligible but haven’t yet received one.

There is mounting evidence that putting off a booster shot is risky, as immunity to COVID-19 wanes in the months following the completion of the primary vaccination series.

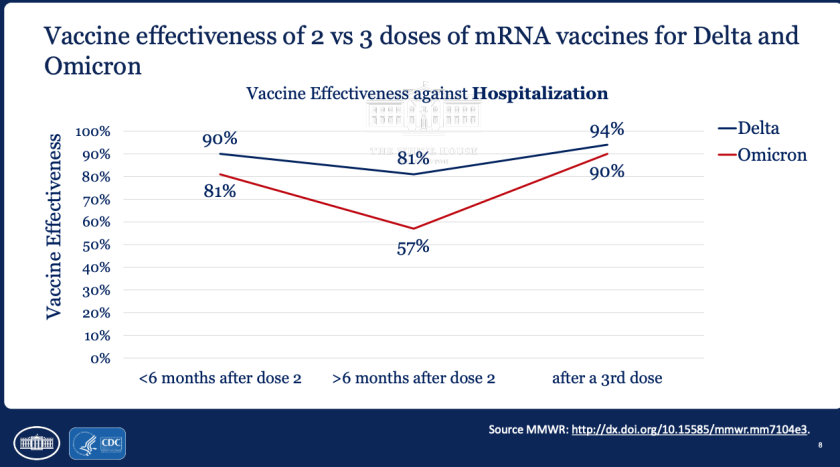

Data presented by Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, showed that for the Omicron variant, two doses of the primary Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna vaccination series resulted in effectiveness against hospitalization falling to just 57% more than six months after the second dose. A booster shot pushed vaccine effectiveness against hospitalization up to 90%.

That study didn’t examine the single-shot vaccine from Johnson & Johnson, which does not use the same mRNA technology as Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna. However, U.S. health officials in December said it’s generally preferable to use either of the mRNA vaccines over Johnson & Johnson — for both the primary series and booster doses — citing the risk for rare but serious blood clots.

The stories shaping California

Get up to speed with our Essential California newsletter, sent six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Rong-Gong Lin II is a metro reporter based in San Francisco who specializes in covering statewide earthquake safety issues and the COVID-19 pandemic. The Bay Area native is a graduate of UC Berkeley and started at the Los Angeles Times in 2004.

Luke Money is a Metro reporter covering breaking news at the Los Angeles Times. He previously was a reporter and assistant city editor for the Daily Pilot, a Times Community News publication in Orange County, and before that wrote for the Santa Clarita Valley Signal. He earned his bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Arizona.

Emily Alpert Reyes covers public health for the Los Angeles Times.