begin quote from:

Marek

Filipiak, a 32-year-old delivery manager at Royal Mail Plc, moved to

London from Poland 13 years ago to study and stayed on to take advantage

of the U.K.’s booming labor market. After …

Brexit ‘Disaster’ Has Poles Thinking About a Return Home

Companies are urging scared EU workers to stay in post-Brexit Britain.

It’s not just the uncertainty over the terms the U.K. might impose on EU workers that worries him, or even a spate of xenophobic incidents that followed the June 23 referendum. A more important factor: the 8.2 percent drop in the British pound against the Polish zloty, which makes it harder for Filipiak to pay his mortgage on an apartment in Poland.

“It’s a disaster,” he said. “If the pound dramatically drops, I might consider going back home early and try my luck in Poland.”

Anxiety about immigration fueled the Brexit vote, and the Conservative Party’s contenders to replace Prime Minister David Cameron have vowed to reduce net migration from a near record 330,000 in 2015. As the Tories talk tough, U.K. employers who rely on immigrant workers are rushing to reassure them they’re wanted and needed, urging them to sit tight while the U.K. government negotiates a new relationship with the EU.

Business Letter

Five of the biggest business groups in the U.K., including the Confederation of British Industry and the British Chambers of Commerce, wrote an open letter Tuesday calling on the government to reaffirm the long-term rights of EU nationals working in Britain. Eighty members of Parliament followed with a similar plea.“Their skills are crucial to the success of our businesses, both now and into the future,” they wrote. With the unemployment rate at an 11-year low of 5 percent, U.K. employers say they need access to the EU labor pool.

Take Mark Gorton, founder of Traditional Norfolk Poultry, which sells 30 million pounds ($39.5 million) worth of free-range poultry annually from a farm in Northeast England. More than 60 percent of his 250-person staff is from Eastern Europe, doing jobs that he says many local Britons don’t want to do: feeding, inspecting and packaging chicken. The referendum result means they don’t know where they stand.

Mark Gorton.

Source: TNP

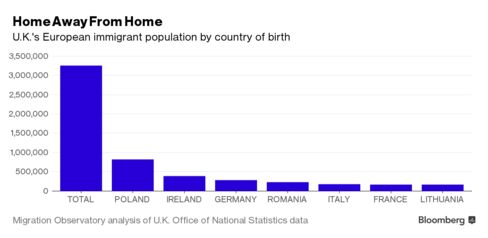

It’s these low-skilled workers from the EU who could face the tightest restrictions. If the U.K. imposes the same conditions on would-be EU migrants that it currently applies to those from most non-EU countries, very few would qualify for work visas, said Carlos Vargas-Silva, senior researcher at Oxford University’s Migration Observatory.

Slowing Economy

Agriculture, restaurants, hotels and the fishing industry would be hardest hit if skill-based selection criteria were applied to EU workers, Vargas-Silva said.Some politicians have warned of a last-minute rush of migrants hoping to get into the U.K. before the rules change. After that, with the pound falling and investment stuttering, the number of EU citizens flocking to the U.K. may slow down naturally as businesses freeze or delay hiring.

“Migration is always driven by the conditions of the U.K. economy,” Vargas-Silva said. “Even if rules don’t change but the economy changes, it will affect migration patterns.”

A woman looks in the window of a Polish shop in the centre of the border town of Berwick-upon-Tweed in northern England.

Photographer: Oli Scarff/AFP via Getty Images

With a cloud of uncertainty hanging over EU citizens in the U.K., Eastern European governments are making a play to lure their people back. Poland’s Deputy Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki said last week that the government is considering incentives to entice Poles to return, including steps to simplify rules for small business.

“I would be happy if there was a six-digit figure of Poles returning from Great Britain,” he said. “Poland will be creating some 200,000 jobs annually as of this year and we believe that those who would potentially come back would create jobs themselves.”

‘Unwelcome Climate’

The government is targeting Polish expatriates like Jacek Ambrozy. After arriving in the U.K. in 2005, he started his own business, IBB Polish Building Wholesale, selling construction materials that he imports from Poland. Post-Brexit, Ambrozy has two problems: worried Polish employees and a worsening exchange rate that he says is costing him £2,400 a week.“The unwelcome climate will for sure limit the number of new immigrants,” he said. “And some immigrants might decide to go back to Poland.”

Ambrozy said he plans to open a warehouse in Poland next year to build his business there “just in case.” One of his 12 Polish employees in the U.K. called him the day after the referendum asking if he could get his salary paid in advance.

“I asked him why and he said, ‘Because now anything can happen,’ ” Ambrozy said. “He was really frightened.”

No comments:

Post a Comment