Major provinces

| Portuguese India (1505–1961) | |

|---|---|

| East India Company | 1612–1757 |

| Company rule in India | 1757–1858 |

| British Raj | 1858–1947 |

| British rule in Burma | 1824–1948 |

11 more rows

British Raj - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Raj

People also ask

British India 1763 - 1815 - History Home

www.historyhome.co.uk/c-eight/india/india.htm

Jan 12, 2016 - The British government gradually took over from the Company the right to ... the work of the East India Company but did not take power for itself.

This system of governance was instituted on 28 June 1858,

when, after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the rule of the British East

India Company was transferred to the Crown in the person of Queen

Victoria (who, in 1876, was proclaimed Empress of India).

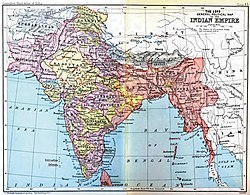

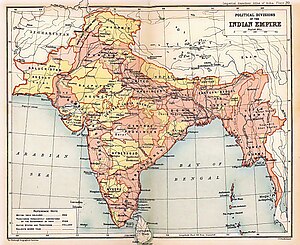

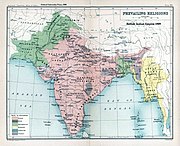

The British Raj (/rɑːdʒ/; from rāj, literally, "rule" in Hindustani)[2] was the rule by the British Crown in the Indian subcontinent between 1858 and 1947.[3][4][5][6] The rule is also called Crown rule in India,[7] or direct rule in India.[8] The region under British control was commonly called India in contemporaneous usage, and included areas directly administered by the United Kingdom, which were collectively called British India, and those ruled by indigenous rulers, but under British tutelage or paramountcy, and called the princely states. The de facto political amalgamation was also called the Indian Empire and after 1876 issued passports under that name.[9][10] As India, it was a founding member of the League of Nations, a participating nation in the Summer Olympics in 1900, 1920, 1928, 1932, and 1936, and a founding member of the United Nations in San Francisco in 1945.[11]

This system of governance was instituted on 28 June 1858, when, after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the rule of the British East India Company was transferred to the Crown in the person of Queen Victoria[12] (who, in 1876, was proclaimed Empress of India). It lasted until 1947, when Britain′s Indian Empire was partitioned into two sovereign dominion states: the Dominion of India (later the Republic of India) and the Dominion of Pakistan (later the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, the eastern part of which, still later, became the People's Republic of Bangladesh). At the inception of the Raj in 1858, Lower Burma was already a part of British India; Upper Burma was added in 1886, and the resulting union, Burma, was administered as an autonomous province until 1937, when it became a separate British colony, gaining its own independence in 1948.

The British Raj extended over almost all present-day India, Pakistan,

and Bangladesh, except for small holdings by other European nations

such as Goa and Pondicherry.[13]

This area is very diverse, containing the Himalayan mountains, fertile

floodplains, the Indo-Gangetic Plain, a long coastline, tropical dry

forests, arid uplands, and the Thar desert.[14] In addition, at various times, it included Aden (from 1858 to 1937),[15] Lower Burma (from 1858 to 1937), Upper Burma (from 1886 to 1937), British Somaliland (briefly from 1884 to 1898), and Singapore

(briefly from 1858 to 1867). Burma was separated from India and

directly administered by the British Crown from 1937 until its

independence in 1948. The Trucial States of the Persian Gulf and the states under the Persian Gulf Residency were theoretically princely states as well as Presidencies and provinces of British India until 1947 and used the rupee as their unit of currency.[16]

Among other countries in the region, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) was ceded to Britain in 1802 under the Treaty of Amiens. Ceylon was part of Madras Presidency between 1793 and 1798.[17] The kingdoms of Nepal and Bhutan, having fought wars with the British, subsequently signed treaties with them and were recognised by the British as independent states.[18][19] The Kingdom of Sikkim was established as a princely state after the Anglo-Sikkimese Treaty of 1861; however, the issue of sovereignty was left undefined.[20] The Maldive Islands were a British protectorate from 1887 to 1965, but not part of British India.

The terms "Indian Empire" and "Empire of India" (like the term "British Empire") were not used in legislation. The monarch was known as Empress or Emperor of India and the term was often used in Queen Victoria's Queen's Speeches and Prorogation Speeches. The passports issued by the British Indian government had the words "Indian Empire" on the cover and "Empire of India" on the inside.[24] In addition, an order of knighthood, the Most Eminent Order of the Indian Empire, was set up in 1878.

Suzerainty over 175 princely states, some of the largest and most important, was exercised (in the name of the British Crown) by the central government of British India under the Viceroy; the remaining approximately 500 states were dependents of the provincial governments of British India under a Governor, Lieutenant-Governor, or Chief Commissioner (as the case might have been).[25] A clear distinction between "dominion" and "suzerainty" was supplied by the jurisdiction of the courts of law: the law of British India rested upon the laws passed by the British Parliament and the legislative powers those laws vested in the various governments of British India, both central and local; in contrast, the courts of the Princely States existed under the authority of the respective rulers of those states.[25]

At the turn of the 20th century, British India consisted of eight

provinces that were administered either by a Governor or a

Lieutenant-Governor.

During the partition of Bengal (1905–1913), the new provinces of

Assam and East Bengal were created as a Lieutenant-Governorship. In

1911, East Bengal was reunited with Bengal, and the new provinces in the east became: Assam, Bengal, Bihar and Orissa.[26]

In addition, there were a few minor provinces that were administered by a Chief Commissioner:[27]

A Princely State, also called a Native State or an Indian State, was a

nominally sovereign entity with an indigenous Indian ruler, subject to a

subsidiary alliance.[28]

There were 565 princely states when India and Pakistan became

independent from Britain in August 1947. The princely states did not

form a part of British India

(i.e. the presidencies and provinces), as they were not directly under

British rule. The larger ones had treaties with Britain that specified

which rights the princes had; in the smaller ones the princes had few

rights. Within the princely states external affairs, defence and most

communications were under British control.[29]

The British also exercised a general influence over the states'

internal politics, in part through the granting or withholding of

recognition of individual rulers. Although there were nearly 600

princely states, the great majority were very small and contracted out

the business of government to the British. Some two hundred of the

states had an area of less than 25 square kilometres (10 square miles).[28]

The states were grouped into Agencies and Residencies.

Following the Indian Rebellion of 1857 (usually called the Indian Mutiny by the British), the Government of India Act 1858 made changes in the governance of India at three levels:

In Calcutta, the Governor-General remained head of the Government of India and now was more commonly called the Viceroy on account of his secondary role as the Crown's representative to the nominally sovereign princely states; he was, however, now responsible to the Secretary of State in London and through him to Parliament. A system of "double government" had already been in place during the Company's rule in India from the time of Pitt's India Act of 1784. The Governor-General in the capital, Calcutta, and the Governor in a subordinate presidency (Madras or Bombay) was each required to consult his advisory council; executive orders in Calcutta, for example, were issued in the name of "Governor-General-in-Council" (i.e. the Governor-General with the advice of the Council). The Company's system of "double government" had its critics, since, from the time of the system's inception, there had been intermittent feuding between the Governor-General and his Council; still, the Act of 1858 made no major changes in governance.[34] However, in the years immediately thereafter, which were also the years of post-rebellion reconstruction, Viceroy Lord Canning found the collective decision making of the Council to be too time-consuming for the pressing tasks ahead, so he requested the "portfolio system" of an Executive Council in which the business of each government department (the "portfolio") was assigned to and became the responsibility of a single council member.[33] Routine departmental decisions were made exclusively by the member, but important decisions required the consent of the Governor-General and, in the absence of such consent, required discussion by the entire Executive Council. This innovation in Indian governance was promulgated in the Indian Councils Act 1861.

If the Government of India needed to enact new laws, the Councils Act allowed for a Legislative Council—an expansion of the Executive Council by up to twelve additional members, each appointed to a two-year term—with half the members consisting of British officials of the government (termed official) and allowed to vote, and the other half, comprising Indians and domiciled Britons in India (termed non-official) and serving only in an advisory capacity.[35] All laws enacted by Legislative Councils in India, whether by the Imperial Legislative Council in Calcutta or by the provincial ones in Madras and Bombay, required the final assent of the Secretary of State in London; this prompted Sir Charles Wood, the second Secretary of State, to describe the Government of India as "a despotism controlled from home".[33] Moreover, although the appointment of Indians to the Legislative Council was a response to calls after the 1857 rebellion, most notably by Sayyid Ahmad Khan, for more consultation with Indians, the Indians so appointed were from the landed aristocracy, often chosen for their loyalty, and far from representative.[36] Even so, the "... tiny advances in the practice of representative government were intended to provide safety valves for the expression of public opinion, which had been so badly misjudged before the rebellion".[37] Indian affairs now also came to be more closely examined in the British Parliament and more widely discussed in the British press.[38]

With the promulgation of the Government of India Act 1935, the Council of India was abolished with effect from 1 April 1937 and a modified system of government enacted. The Secretary of State for India represented the Government of India in the UK. He was assisted by a body of advisers numbering from 8–12 individuals, at least half of whom were required to have held office in India for a minimum of 10 years, and had not relinquished office earlier than two years prior to their appointment as advisers to the Secretary of State.[39]

The Viceroy and Governor-General of India, a Crown appointee, typically held office for five years though there was no fixed tenure, and received an annual salary of Rs. 250,800 p.a. (£18,810 p.a.).[39][40] He headed the Viceroy's Executive Council, each member of which had responsibility for a department of the central administration. From 1 April 1937, the position of Governor-General in Council, which the Viceroy and Governor-General concurrently held in the capacity of representing the Crown in relations with the Indian princely states, was replaced by the designation of "HM Representative for the Exercise of the Functions of the Crown in its Relations with the Indian States," or the "Crown Representative." The Executive Council was greatly expanded during the Second World War, and in 1947 comprised 14 Members (Secretaries), each of whom earned a salary of Rs. 66,000 p.a. (£4950 p.a.). The portfolios in 1946–1947 were:

The Viceroy and Governor-General was also the head of the bicameral Indian Legislature, consisting of an upper house (the Council of State) and a lower house (the Legislative Assembly). The Viceroy was the head of the Council of State, while the Legislative Assembly, which was first opened in 1921, was headed by an elected President (appointed by the Viceroy from 1921–1925). The Council of State consisted of 58 members (32 elected, 26 nominated), while the Legislative Assembly comprised 141 members (26 nominated officials, 13 others nominated and 102 elected). The Council of State existed in five-year periods and the Legislative Assembly for three-year periods, though either could be dissolved earlier or later by the Viceroy. The Indian Legislature was empowered to make laws for all persons resident in British India including all British subjects resident in India, and for all British Indian subjects residing outside India. With the assent of the King-Emperor and after copies of a proposed enactment had been submitted to both houses of the British Parliament, the Viceroy could overrule the legislature and directly enact any measures in the perceived interests of British India or its residents if the need arose.[42]

Effective from 1 April 1936, the Government of India Act created the new provinces of Sind (separated from the Bombay Presidency) and Orissa (separated from the Province of Bihar and Orissa). Burma and Aden became separate Crown Colonies under the Act from 1 April 1937, thereby ceasing to be part of the Indian Empire. From 1937 onwards, British India was divided into 17 administrations: the three Presidencies of Madras, Bombay and Bengal, and the 14 provinces of the United Provinces, Punjab, Bihar, the Central Provinces and Berar, Assam, the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP), Orissa, Sind, British Baluchistan, Delhi, Ajmer-Merwara, Coorg, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands and Panth Piploda. The Presidencies and the first eight provinces were each under a Governor, while the latter six provinces were each under a Chief Commissioner. The Viceroy directly governed the Chief Commissioner provinces through each respective Chief Commissioner, while the Presidencies and the provinces under Governors were allowed greater autonomy under the Government of India Act.[43][44] Each Presidency or province headed by a Governor had either a provincial bicameral legislature (in the Presidencies, the United Provinces, Bihar and Assam) or a unicameral legislature (in the Punjab, Central Provinces and Berar, NWFP, Orissa and Sind). The Governor of each presidency or province represented the Crown in his capacity, and was assisted by a ministers appointed from the members of each provincial legislature. Each provincial legislature had a life of five years, barring any special circumstances such as wartime conditions. All bills passed by the provincial legislature were either signed or rejected by the Governor, who could also issue proclamations or promulgate ordinances while the legislature was in recess, as the need arose.[44]

Each province or presidency comprised a number of divisions, each headed by a Commissioner and subdivided into districts, which were the basic administrative units and each headed by a Collector and Magistrate or Deputy Commissioner; in 1947, British India comprised 230 districts.[44]

Although the rebellion

had shaken the British enterprise in India, it had not derailed it.

After the war, the British became more circumspect. Much thought was

devoted to the causes of the rebellion, and from it three main lessons

were drawn. At a more practical level, it was felt that there needed to

be more communication and camaraderie between the British and

Indians—not just between British army officers and their Indian staff

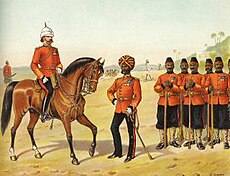

but in civilian life as well.[57] The Indian army was completely reorganised: units composed of the Muslims and Brahmins of the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh,

who had formed the core of the rebellion, were disbanded. New

regiments, like the Sikhs and Baluchis, composed of Indians who, in

British estimation, had demonstrated steadfastness, were formed. From

then on, the Indian army was to remain unchanged in its organisation

until 1947.[58]

The 1861 Census had revealed that the English population in India was

125,945. Of these only about 41,862 were civilians as compared with

about 84,083 European officers and men of the Army.[59]

In 1880, the standing Indian Army consisted of 66,000 British soldiers,

130,000 Natives, and 350,000 soldiers in the princely armies.[60]

It was also felt that both the princes and the large land-holders, by

not joining the rebellion, had proved to be, in Lord Canning's words,

"breakwaters in a storm".[57]

They too were rewarded in the new British Raj by being officially

recognised in the treaties each state now signed with the Crown.[61][not in citation given]

At the same time, it was felt that the peasants, for whose benefit the

large land-reforms of the United Provinces had been undertaken, had

shown disloyalty, by, in many cases, fighting for their former landlords

against the British. Consequently, no more land reforms were

implemented for the next 90 years: Bengal and Bihar were to remain the

realms of large land holdings (unlike the Punjab and Uttar Pradesh).[62]

Lastly, the British felt disenchanted with Indian reaction to social change. Until the rebellion, they had enthusiastically pushed through social reform, like the ban on sati by Lord William Bentinck.[63] It was now felt that traditions and customs in India were too strong and too rigid to be changed easily; consequently, no more British social interventions were made, especially in matters dealing with religion,[61] even when the British felt very strongly about the issue (as in the instance of the remarriage of Hindu child widows).[64] This was exemplified further in Queen Victoria's Proclamation released immediately after the rebellion. The proclamation stated that 'We disclaim alike our Right and Desire to impose Our Convictions on any of Our Subjects';[65] demonstrating official British commitment to abstaining from social intervention in India.

Studies of India's population since 1881 have focused on such topics as total population, birth and death rates, growth rates, geographic distribution, literacy, the rural and urban divide, cities of a million, and the three cities with populations over eight million: Delhi, Greater Bombay, and Calcutta.[70]

Mortality rates fell in 1920–45 era, primarily due to biological immunisation. Other factors included rising incomes and better living conditions, improved better nutrition, a safer and cleaner environment, and better official health policies and medical care.[71]

Severe overcrowding in the cities caused major public health problems, as noted in an official report from 1938:[72]

Singha argues that after 1857 the colonial government strengthened

and expanded its infrastructure via the court system, legal procedures,

and statutes. New legislation merged the Crown and the old East India

Company courts and introduced a new penal code as well as new codes of

civil and criminal procedure, based largely on English law. In the

1860s–1880s the Raj set up compulsory registration of births, deaths,

and marriages, as well as adoptions, property deeds, and wills. The goal

was to create a stable, usable public record and verifiable identities.

However, there was opposition from both Muslim and Hindu elements who

complained that the new procedures for census-taking and registration

threatened to uncover female privacy. Purdah

rules prohibited women from saying their husband's name or having their

photograph taken. An all-India census was conducted between 1868 and

1871, often using total numbers of females in a household rather than

individual names. Select groups which the Raj reformers wanted to

monitor statistically included those reputed to practice female infanticide, prostitutes, lepers, and eunuchs.[73]

Murshid argues that women were in some ways more restricted by the modernisation of the laws. They remained tied to the strictures of their religion, caste, and customs, but now with an overlay of British Victorian attitudes. Their inheritance rights to own and manage property were curtailed; the new English laws were somewhat harsher. Court rulings restricted the rights of second wives and their children regarding inheritance. A woman had to belong to either a father or a husband to have any rights.[74]

Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800–1859) presented his Whiggish interpretation of English history

as an upward progression always leading to more liberty and more

progress. Macaulay simultaneously was a leading reformer involved in

transforming the educational system of India. He would base it on the

English language so that India could join the mother country in a steady

upward progress. Macaulay took Burke's emphasis on moral rule and

implemented it in actual school reforms, giving the British Empire a

profound moral mission to civilise the natives.

Yale professor Karuna Mantena has argued that the civilising mission did not last long, for she says that benevolent reformers were the losers in key debates, such as those following the 1857 rebellion in India, and the scandal of Governor Edward Eyre's brutal repression of the Morant Bay rebellion in Jamaica in 1865. The rhetoric continued but it became an alibi for British misrule and racism. No longer was it believed that the natives could truly make progress, instead they had to be ruled by heavy hand, with democratic opportunities postponed indefinitely. As a result:

The British made widespread education in English a high priority.[77]

During the time of the East India Company, Thomas Babington Macaulay

had made schooling taught in English a priority for the Raj in his

famous minute of February 1835 and succeeded in implementing ideas

previously put forward by Lord William Bentinck (the governor general

between 1828 and 1835). Bentinck favoured the replacement of Persian by

English as the official language, the use of English as the medium of

instruction, and the training of English-speaking Indians as teachers.

He was inspired by utilitarian ideas and called for "useful learning."

However, Bentinck's proposals were rejected by London officials.[78][79] Under Macaulay, thousands of elementary and secondary schools were opened; they typically had an all-male student body.

Missionaries opened their own schools that taught Christianity and the 3-Rs. Bellenoit argues that as civil servants became more isolated and resorted to scientific racism, missionary schools became more engaged with Indians, grew increasingly sympathetic to Indian culture, and adamantly opposed scientific racism.[80]

Universities in Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras were established in 1857, just before the Rebellion. By 1890 some 60,000 Indians had matriculated, chiefly in the liberal arts or law. About a third entered public administration, and another third became lawyers. The result was a very well educated professional state bureaucracy. By 1887 of 21,000 mid-level civil service appointments, 45% were held by Hindus, 7% by Muslims, 19% by Eurasians (European father and Indian mother), and 29% by Europeans. Of the 1000 top-level positions, almost all were held by Britons, typically with an Oxbridge degree.[81] The government, often working with local philanthropists, opened 186 universities and colleges of higher education by 1911; they enrolled 36,000 students (over 90% men). By 1939 the number of institutions had doubled and enrolment reached 145,000. The curriculum followed classical British standards of the sort set by Oxford and Cambridge and stressed English literature and European history. Nevertheless, by the 1920s the student bodies had become hotbeds of Indian nationalism.[82]

In the 1890s, he launched plans to move into heavy industry using Indian funding. The Raj did not provide capital, but, aware of Britain's declining position against the US and Germany in the steel industry, it wanted steel mills in India. It promised to purchase any surplus steel Tata could not otherwise sell.[89] The Tata Iron and Steel Company (TISCO), now headed by his son Dorabji Tata (1859–1932), opened its plant at Jamshedpur in Bihar in 1908. It used American technology, not British[90] and became the leading iron and steel producer in India, with 120,000 employees in 1945. TISCO became India's proud symbol of technical skill, managerial competence, entrepreneurial flair, and high pay for industrial workers.[91] The Tata family, like most of India's big businessmen, were Indian nationalists but did not trust the Congress because it seemed too aggressively hostile to the Raj, too socialist, and too supportive of trade unions.[92]

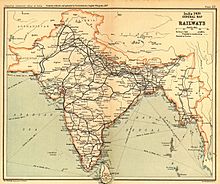

British India built a modern railway system in the late nineteenth

century which was the fourth largest in the world. The railways at first

were privately owned and operated. It was run by British

administrators, engineers and craftsmen. At first, only the unskilled

workers were Indians.[93]

The East India Company (and later the colonial government) encouraged new railway companies backed by private investors under a scheme that would provide land and guarantee an annual return of up to five percent during the initial years of operation. The companies were to build and operate the lines under a 99-year lease, with the government having the option to buy them earlier.[94]

Two new railway companies, Great Indian Peninsular Railway (GIPR) and East Indian Railway (EIR) began in 1853–54 to construct and operate lines near Bombay and Calcutta. The first passenger railway line in North India between Allahabad and Kanpur opened in 1859.

In 1854, Governor-General Lord Dalhousie formulated a plan to construct a network of trunk lines connecting the principal regions of India. Encouraged by the government guarantees, investment flowed in and a series of new rail companies were established, leading to rapid expansion of the rail system in India.[95] Soon several large princely states built their own rail systems and the network spread to the regions that became the modern-day states of Assam, Rajasthan and Andhra Pradesh. The route mileage of this network increased from 1,349 kilometres (838 mi) in 1860 to 25,495 kilometres (15,842 mi) in 1880, mostly radiating inland from the three major port cities of Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta.[96]

Most of the railway construction was done by Indian companies supervised by British engineers.[97] The system was heavily built, using a wide gauge, sturdy tracks and strong bridges. By 1900 India had a full range of rail services with diverse ownership and management, operating on broad, metre and narrow gauge networks. In 1900, the government took over the GIPR network, while the company continued to manage it.[97] During the First World War, the railways were used to transport troops and grains to the ports of Bombay and Karachi en route to Britain, Mesopotamia, and East Africa. With shipments of equipment and parts from Britain curtailed, maintenance became much more difficult; critical workers entered the army; workshops were converted to making artillery; some locomotives and cars were shipped to the Middle East. The railways could barely keep up with the increased demand.[98] By the end of the war, the railways had deteriorated for lack of maintenance and were not profitable. In 1923, both GIPR and EIR were nationalised.[99][100]

Headrick shows that until the 1930s, both the Raj lines and the private companies hired only European supervisors, civil engineers, and even operating personnel, such as locomotive engineers. The government's Stores Policy required that bids on railway contracts be made to the India Office in London, shutting out most Indian firms.[100] The railway companies purchased most of their hardware and parts in Britain. There were railway maintenance workshops in India, but they were rarely allowed to manufacture or repair locomotives. TISCO steel could not obtain orders for rails until the war emergency.[101]

The Second World War severely crippled the railways as rolling stock was diverted to the Middle East, and the railway workshops were converted into munitions workshops.[102] After independence in 1947, forty-two separate railway systems, including thirty-two lines owned by the former Indian princely states, were amalgamated to form a single nationalised unit named the Indian Railways.

India provides an example of the British Empire pouring its money and expertise into a very well built system designed for military reasons (after the Mutiny of 1857), with the hope that it would stimulate industry. The system was overbuilt and too expensive for the small amount of freight traffic it carried. Christensen (1996), who looked at colonial purpose, local needs, capital, service, and private-versus-public interests, concluded that making the railways a creature of the state hindered success because railway expenses had to go through the same time-consuming and political budgeting process as did all other state expenses. Railway costs could therefore not be tailored to the timely needs of the railways or their passengers.[103]

Taxes in India decreased during the colonial period for most of

India's population; with the land tax revenue claiming 15% of India's

national income during Mogul times compared with 1% at the end of the

colonial period. The percentage of national income for the village

economy increased from 44% during Mogul times to 54% by the end of

colonial period. India's per capita GDP decreased from $550[clarification needed] in 1700 to $520 by 1857, although it later increased to $618, by 1947.[113]

— Jawaharlal Nehru, on the economic effects of the British rule, in his book The Discovery of India[114]

Historians continue to debate whether the long-term impact of British

rule was to accelerate the economic development of India, or to distort

and retard it. In 1780, the conservative British politician Edmund Burke raised the issue of India's position: he vehemently attacked the East India Company, claiming that Warren Hastings

and other top officials had ruined the Indian economy and society.

Indian historian Rajat Kanta Ray (1998) continues this line of attack,

saying the new economy brought by the British in the 18th century was a

form of "plunder" and a catastrophe for the traditional economy of the Mughal Empire.[115] Ray accuses the British of depleting the food and money stocks and of imposing high taxes that helped cause the terrible Bengal famine of 1770, which killed a third of the people of Bengal.[116]

P. J. Marshall shows that recent scholarship has reinterpreted the view that the prosperity of the formerly benign Mughal rule gave way to poverty and anarchy.[117] He argues the British takeover did not make any sharp break with the past, which largely delegated control to regional Mughal rulers and sustained a generally prosperous economy for the rest of the 18th century. Marshall notes the British went into partnership with Indian bankers and raised revenue through local tax administrators and kept the old Mughal rates of taxation.

Many historians agree that the East India Company inherited an onerous taxation system that took one-third of the produce of Indian cultivators.[115] Instead of the Indian nationalist account of the British as alien aggressors, seizing power by brute force and impoverishing all of India, Marshall presents the interpretation (supported by many scholars in India and the West) that the British were not in full control but instead were players in what was primarily an Indian play and in which their rise to power depended upon excellent co-operation with Indian elites.[117] Marshall admits that much of his interpretation is still highly controversial among many historians.[118]

During the British Raj, India experienced some of the worst famines ever recorded, including the Great Famine of 1876–1878, in which 6.1 million to 10.3 million people died[133] and the Indian famine of 1899–1900, in which 1.25 to 10 million people died.[134] Recent research, including work by Mike Davis and Amartya Sen,[135] argue that famines in India were made more severe by British polices in India. An El Niño event caused the Indian famine of 1876–1878.[136]

Having been criticised for the badly bungled relief-effort during the Orissa famine of 1866,[137] British authorities began to discuss famine policy soon afterwards, and in early 1868 Sir William Muir, Lieutenant-Governor of the North Western Provinces, issued a famous order stating that:[138]

Fevers ranked as one of the leading causes of death in India in the 19th century.[142] Britain's Sir Ronald Ross, working in the Presidency General Hospital in Calcutta, finally proved in 1898 that mosquitoes transmit malaria, while on assignment in the Deccan at Secunderabad, where the Center for Tropical and Communicable Diseases is now named in his honour.[143]

In 1881, around 120,000 leprosy patients existed in India. The central government passed the Lepers Act of 1898, which provided legal provision for forcible confinement of leprosy sufferers in India.[144] Under the direction of Mountstuart Elphinstone a program was launched to propagate smallpox vaccination.[145] Mass vaccination in India resulted in a major decline in smallpox mortality by the end of the 19th century.[146] In 1849 nearly 13% of all Calcutta deaths were due to smallpox.[147] Between 1868 and 1907, there were approximately 4.7 million deaths from smallpox.[148]

Sir Robert Grant directed his attention to establishing a systematic institution in Bombay for imparting medical knowledge to the natives.[149] In 1860, Grant Medical College became one of the four recognised colleges for teaching courses leading to degrees (alongside Elphinstone College, Deccan College and Government Law College, Mumbai).[117]

It was, however, Viceroy Lord Ripon's partial reversal of the Ilbert Bill (1883), a legislative measure that had proposed putting Indian judges in the Bengal Presidency on equal footing with British ones, that transformed the discontent into political action.[153] On 28 December 1885, professionals and intellectuals from this middle-class—many educated at the new British-founded universities in Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras, and familiar with the ideas of British political philosophers, especially the utilitarians assembled in Bombay. The seventy men founded the Indian National Congress; Womesh Chandra Bonerjee was elected the first president. The membership comprised a westernised elite, and no effort was made at this time to broaden the base.

During its first twenty years, the Congress primarily debated British policy toward India; however, its debates created a new Indian outlook that held Great Britain responsible for draining India of its wealth. Britain did this, the nationalists claimed, by unfair trade, by the restraint on indigenous Indian industry, and by the use of Indian taxes to pay the high salaries of the British civil servants in India.[154]

Social reform was in the air by the 1880s. For example, Pandita Ramabai,

poet, Sanskrit scholar, and a champion of the emancipation of Indian

women, took up the cause of widow remarriage, especially of Brahamin

widows, later converted to Christianity.[156] By 1900 reform movements had taken root within the Indian National Congress. Congress member Gopal Krishna Gokhale founded the Servants of India Society,

which lobbied for legislative reform (for example, for a law to permit

the remarriage of Hindu child widows), and whose members took vows of

poverty, and worked among the untouchable community.[157]

By 1905, a deep gulf opened between the moderates, led by Gokhale, who downplayed public agitation, and the new "extremists" who not only advocated agitation, but also regarded the pursuit of social reform as a distraction from nationalism. Prominent among the extremists was Bal Gangadhar Tilak, who attempted to mobilise Indians by appealing to an explicitly Hindu political identity, displayed, for example, in the annual public Ganapati festivals that he inaugurated in western India.[158]

The then Viceroy, Lord Curzon (1899–1905) was unusually energetic in pursuit of efficiency and reform.[159] His agenda included the creation of the North-West Frontier Province; small changes in the Civil Service;

speeding up the operations of the secretariat; setting up a gold

standard to ensure a stable currency; creation of a Railway Board;

irrigation reform; reduction of peasant debts; lowering the cost of

telegrams; archaeological research and the preservation of antiquities;

improvements in the universities; police reforms; upgrading the roles of

the Native States; a new Commerce and Industry Department; promotion of

industry; revised land revenue policies; lowering taxes; setting up

agricultural banks; creating an Agricultural Department; sponsoring

agricultural research; establishing an Imperial Library; creating an

Imperial Cadet Corps; new famine codes; and, indeed, reducing the smoke

nuisance in Calcutta.[160]

Trouble emerged for Curzon when he divided the largest administrative subdivision in British India, the Bengal Province, into the Muslim-majority province of Eastern Bengal and Assam and the Hindu-majority province of West Bengal (present-day Indian states of West Bengal, Bihar, and Odisha). Curzon's act, the Partition of Bengal—which some considered administratively felicitous, communally charged, sowed the seeds of division among Indians in Bengal and, which had been contemplated by various colonial administrations since the time of Lord William Bentinck, but never acted upon—was to transform nationalist politics as nothing else before it. The Hindu elite of Bengal, among them many who owned land in East Bengal that was leased out to Muslim peasants, protested fervidly.[161]

Following the Partition of Bengal, which was a strategy set out by Lord Curzon to weaken the nationalist movement, Tilak encouraged the Swadeshi movement and the Boycott movement.[162] The movement consisted of the boycott of foreign goods and also the social boycott of any Indian who used foreign goods. The Swadeshi movement consisted of the usage of natively produced goods. Once foreign goods were boycotted, there was a gap which had to be filled by the production of those goods in India itself. Bal Gangadhar Tilak said that the Swadeshi and Boycott movements are two sides of the same coin. The large Bengali Hindu middle-class (the Bhadralok), upset at the prospect of Bengalis being outnumbered in the new Bengal province by Biharis and Oriyas, felt that Curzon's act was punishment for their political assertiveness. The pervasive protests against Curzon's decision took the form predominantly of the Swadeshi ("buy Indian") campaign led by two-time Congress president, Surendranath Banerjee, and involved boycott of British goods.[163]

The rallying cry for both types of protest was the slogan Bande Mataram ("Hail to the Mother"), which invoked a mother goddess, who stood variously for Bengal, India, and the Hindu goddess Kali. Sri Aurobindo never went beyond the law when he edited the Bande Mataram magazine; it preached independence but within the bounds of peace as far as possible. Its goal was Passive Resistance.[164] The unrest spread from Calcutta to the surrounding regions of Bengal when students returned home to their villages and towns. Some joined local political youth clubs emerging in Bengal at the time, some engaged in robberies to fund arms, and even attempted to take the lives of Raj officials. However, the conspiracies generally failed in the face of intense police work.[165] The Swadeshi boycott movement cut imports of British textiles by 25%. The swadeshi cloth, although more expensive and somewhat less comfortable than its Lancashire competitor, was worn as a mark of national pride by people all over India.[166]

The Hindu protests against the partition of Bengal led the Muslim elite in India to organise in 1906 the All India Muslim League.

The League favoured the partition of Bengal, since it gave them a

Muslim majority in the eastern half. In 1905, when Tilak and Lajpat Rai

attempted to rise to leadership positions in the Congress, and the

Congress itself rallied around symbolism of Kali, Muslim fears

increased. The Muslim elite, including Dacca Nawab and Khwaja Salimullah, expected that a new province with a Muslim majority would directly benefit Muslims aspiring to political power.[167]

The first steps were taken toward self-government in British India in the late 19th century with the appointment of Indian counsellors to advise the British viceroy and the establishment of provincial councils with Indian members; the British subsequently widened participation in legislative councils with the Indian Councils Act of 1892. Municipal Corporations and District Boards were created for local administration; they included elected Indian members.

The Indian Councils Act 1909, known as the Morley-Minto Reforms (John Morley was the secretary of state for India, and Minto was viceroy) – gave Indians limited roles in the central and provincial legislatures. Upper class Indians, rich landowners and businessmen were favoured. The Muslim community was made a separate electorate and granted double representation. The goals were quite conservative but they did advance the elective principle.[56]

The partition of Bengal was rescinded in 1911 and announced at the Delhi Durbar at which King George V came in person and was crowned Emperor of India. He announced the capital would be moved from Calcutta to Delhi, a Muslim stronghold. Morley was especially vigilant in crushing revolutionary groups.[168]

The First World War

would prove to be a watershed in the imperial relationship between

Britain and India. Shortly prior to the outbreak of war, the Government

of India had indicated that they could furnish two divisions plus a

cavalry brigade, with a further division in case of emergency.[169] Some 1.4 million Indian and British soldiers of the British Indian Army took part in the war, primarily in Iraq and the Middle East.

Their participation had a wider cultural fallout as news spread how

bravely soldiers fought and died alongside British soldiers, as well as

soldiers from dominions like Canada and Australia.[170] India's international profile rose during the 1920s, as it became a founding member of the League of Nations in 1920 and participated, under the name, "Les Indes Anglaises" (British India), in the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp.[171] Back in India, especially among the leaders of the Indian National Congress, the war led to calls for greater self-government for Indians.[170]

After the 1906 split between the moderates and the extremists, organised political activity by the Congress had remained fragmented until 1914, when Bal Gangadhar Tilak was released from prison and began to sound out other Congress leaders about possible re-unification. That, however, had to wait until the demise of Tilak's principal moderate opponents, Gopal Krishna Gokhale and Pherozeshah Mehta, in 1915, whereupon an agreement was reached for Tilak's ousted group to re-enter the Congress.[170] In the 1916 Lucknow session of the Congress, Tilak's supporters were able to push through a more radical resolution which asked for the British to declare that it was their, "aim and intention ... to confer self-government on India at an early date."[170] Soon, other such rumblings began to appear in public pronouncements: in 1917, in the Imperial Legislative Council, Madan Mohan Malaviya spoke of the expectations the war had generated in India, "I venture to say that the war has put the clock ... fifty years forward ... (The) reforms after the war will have to be such, ... as will satisfy the aspirations of her (India's) people to take their legitimate part in the administration of their own country."[170]

The 1916 Lucknow Session of the Congress was also the venue of an unanticipated mutual effort by the Congress and the Muslim League, the occasion for which was provided by the wartime partnership between Germany and Turkey. Since the Turkish Sultan, or Khalifah, had also sporadically claimed guardianship of the Islamic holy sites of Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem, and since the British and their allies were now in conflict with Turkey, doubts began to increase among some Indian Muslims about the "religious neutrality" of the British, doubts that had already surfaced as a result of the reunification of Bengal in 1911, a decision that was seen as ill-disposed to Muslims.[172] In the Lucknow Pact, the League joined the Congress in the proposal for greater self-government that was campaigned for by Tilak and his supporters; in return, the Congress accepted separate electorates for Muslims in the provincial legislatures as well as the Imperial Legislative Council. In 1916, the Muslim League had anywhere between 500 and 800 members and did not yet have its wider following among Indian Muslims of later years; in the League itself, the pact did not have unanimous backing, having largely been negotiated by a group of "Young Party" Muslims from the United Provinces (UP), most prominently, two brothers Mohammad and Shaukat Ali, who had embraced the Pan-Islamic cause;[172] however, it did have the support of a young lawyer from Bombay, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who was later to rise to leadership roles in both the League and the Indian independence movement. In later years, as the full ramifications of the pact unfolded, it was seen as benefiting the Muslim minority élites of provinces like UP and Bihar more than the Muslim majorities of Punjab and Bengal, nonetheless, at the time, the "Lucknow Pact", was an important milestone in nationalistic agitation and was seen so by the British.[172]

During 1916, two Home Rule Leagues were founded within the Indian National Congress by Tilak and Annie Besant, respectively, to promote Home Rule among Indians, and also to elevate the stature of the founders within the Congress itself.[173] Mrs. Besant, for her part, was also keen to demonstrate the superiority of this new form of organised agitation, which had achieved some success in the Irish home rule movement, to the political violence that had intermittently plagued the subcontinent during the years 1907–1914.[173] The two Leagues focused their attention on complementary geographical regions: Tilak's in western India, in the southern Bombay presidency, and Mrs. Besant's in the rest of the country, but especially in the Madras Presidency and in regions like Sind and Gujarat that had hitherto been considered politically dormant by the Congress.[173] Both leagues rapidly acquired new members – approximately thirty thousand each in a little over a year – and began to publish inexpensive newspapers. Their propaganda also turned to posters, pamphlets, and political-religious songs, and later to mass meetings, which not only attracted greater numbers than in earlier Congress sessions, but also entirely new social groups such as non-Brahmins, traders, farmers, students, and lower-level government workers.[173] Although they did not achieve the magnitude or character of a nationwide mass movement, the Home Rule leagues both deepened and widened organised political agitation for self-rule in India. The British authorities reacted by imposing restrictions on the Leagues, including shutting out students from meetings and banning the two leaders from travelling to certain provinces.[173]

The year 1915 also saw the return of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi to India. Already known in India as a result of his civil liberties protests on behalf of the Indians in South Africa, Gandhi followed the advice of his mentor Gopal Krishna Gokhale and chose not to make any public pronouncements during the first year of his return, but instead spent the year travelling, observing the country first-hand, and writing.[174] Earlier, during his South Africa sojourn, Gandhi, a lawyer by profession, had represented an Indian community, which, although small, was sufficiently diverse to be a microcosm of India itself. In tackling the challenge of holding this community together and simultaneously confronting the colonial authority, he had created a technique of non-violent resistance, which he labelled Satyagraha (or, Striving for Truth).[175] For Gandhi, Satyagraha was different from "passive resistance", by then a familiar technique of social protest, which he regarded as a practical strategy adopted by the weak in the face of superior force; Satyagraha, on the other hand, was for him the "last resort of those strong enough in their commitment to truth to undergo suffering in its cause."[175] Ahimsa or "non-violence", which formed the underpinning of Satyagraha, came to represent the twin pillar, with Truth, of Gandhi's unorthodox religious outlook on life.[175] During the years 1907–1914, Gandhi tested the technique of Satyagraha in a number of protests on behalf of the Indian community in South Africa against the unjust racial laws.[175]

Also, during his time in South Africa, in his essay, Hind Swaraj, (1909), Gandhi formulated his vision of Swaraj, or "self-rule" for India based on three vital ingredients: solidarity between Indians of different faiths, but most of all between Hindus and Muslims; the removal of untouchability from Indian society; and the exercise of swadeshi – the boycott of manufactured foreign goods and the revival of Indian cottage industry.[174] The first two, he felt, were essential for India to be an egalitarian and tolerant society, one befitting the principles of Truth and Ahimsa, while the last, by making Indians more self-reliant, would break the cycle of dependence that was not only perpetrating the direction and tenor of the British rule in India, but also the British commitment to it.[174] At least until 1920, the British presence itself, was not a stumbling block in Gandhi's conception of swaraj; rather, it was the inability of Indians to create a modern society.[174]

Gandhi made his political debut in India in 1917 in Champaran district in Bihar,

near the Nepal border, where he was invited by a group of disgruntled

tenant farmers who, for many years, had been forced into planting indigo

(for dyes) on a portion of their land and then selling it at

below-market prices to the British planters who had leased them the

land.[177] Upon his arrival in the district, Gandhi was joined by other agitators, including a young Congress leader, Rajendra Prasad,

from Bihar, who would become a loyal supporter of Gandhi and go on to

play a prominent role in the Indian independence movement. When Gandhi

was ordered to leave by the local British authorities, he refused on

moral grounds, setting up his refusal as a form of individual Satyagraha.

Soon, under pressure from the Viceroy in Delhi who was anxious to

maintain domestic peace during wartime, the provincial government

rescinded Gandhi's expulsion order, and later agreed to an official

enquiry into the case. Although, the British planters eventually gave

in, they were not won over to the farmers' cause, and thereby did not

produce the optimal outcome of a Satyagraha that Gandhi had hoped for;

similarly, the farmers themselves, although pleased at the resolution,

responded less than enthusiastically to the concurrent projects of rural

empowerment and education that Gandhi had inaugurated in keeping with

his ideal of swaraj. The following year Gandhi launched two more Satyagrahas – both in his native Gujarat – one in the rural Kaira district where land-owning farmers were protesting increased land-revenue and the other in the city of Ahmedabad,

where workers in an Indian-owned textile mill were distressed about

their low wages. The satyagraha in Ahmedabad took the form of Gandhi

fasting and supporting the workers in a strike, which eventually led to a

settlement. In Kaira, in contrast, although the farmers' cause received

publicity from Gandhi's presence, the satyagraha itself, which

consisted of the farmers' collective decision to withhold payment, was

not immediately successful, as the British authorities refused to back

down. The agitation in Kaira gained for Gandhi another lifelong

lieutenant in Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, who had organised the farmers, and who too would go on to play a leadership role in the Indian independence movement.[178] Champaran, Kaira, and Ahmedabad were important milestones in the history of Gandhi's new methods of social protest in India.

In 1916, in the face of new strength demonstrated by the nationalists with the signing of the Lucknow Pact and the founding of the Home Rule leagues, and the realisation, after the disaster in the Mesopotamian campaign, that the war would likely last longer, the new Viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, cautioned that the Government of India needed to be more responsive to Indian opinion.[179] Towards the end of the year, after discussions with the government in London, he suggested that the British demonstrate their good faith – in light of the Indian war role – through a number of public actions, including awards of titles and honours to princes, granting of commissions in the army to Indians, and removal of the much-reviled cotton excise duty, but, most importantly, an announcement of Britain's future plans for India and an indication of some concrete steps. After more discussion, in August 1917, the new Liberal Secretary of State for India, Edwin Montagu, announced the British aim of "increasing association of Indians in every branch of the administration, and the gradual development of self-governing institutions, with a view to the progressive realisation of responsible government in India as an integral part of the British Empire."[179] Although the plan envisioned limited self-government at first only in the provinces – with India emphatically within the British Empire – it represented the first British proposal for any form of representative government in a non-white colony.

Earlier, at the onset of World War I, the reassignment of most of the British army in India to Europe and Mesopotamia, had led the previous Viceroy, Lord Harding, to worry about the "risks involved in denuding India of troops."[170] Revolutionary violence had already been a concern in British India; consequently, in 1915, to strengthen its powers during what it saw was a time of increased vulnerability, the Government of India passed the Defence of India Act, which allowed it to intern politically dangerous dissidents without due process, and added to the power it already had – under the 1910 Press Act – both to imprison journalists without trial and to censor the press.[180] It was under the Defence of India act that the Ali brothers were imprisoned in 1916, and Annie Besant, a European woman, and ordinarily more problematic to imprison, in 1917.[180] Now, as constitutional reform began to be discussed in earnest, the British began to consider how new moderate Indians could be brought into the fold of constitutional politics and, simultaneously, how the hand of established constitutionalists could be strengthened. However, since the Government of India wanted to ensure against any sabotage of the reform process by extremists, and since its reform plan was devised during a time when extremist violence had ebbed as a result of increased governmental control, it also began to consider how some of its wartime powers could be extended into peacetime.[180]

Consequently, in 1917, even as Edwin Montagu, announced the new constitutional reforms, a committee chaired by a British judge, Mr. S. A. T. Rowlatt, was tasked with investigating "revolutionary conspiracies", with the unstated goal of extending the government's wartime powers.[179] The Rowlatt committee presented its report in July 1918 and identified three regions of conspiratorial insurgency: Bengal, the Bombay presidency, and the Punjab.[179] To combat subversive acts in these regions, the committee recommended that the government use emergency powers akin to its wartime authority, which included the ability to try cases of sedition by a panel of three judges and without juries, exaction of securities from suspects, governmental overseeing of residences of suspects,[179] and the power for provincial governments to arrest and detain suspects in short-term detention facilities and without trial.[176]

With the end of World War I, there was also a change in the economic climate. By the end of 1919, 1.5 million Indians had served in the armed services in either combatant or non-combatant roles, and India had provided £146 million in revenue for the war.[181] The increased taxes coupled with disruptions in both domestic and international trade had the effect of approximately doubling the index of overall prices in India between 1914 and 1920.[181] Returning war veterans, especially in the Punjab, created a growing unemployment crisis,[182] and post-war inflation led to food riots in Bombay, Madras, and Bengal provinces,[182] a situation that was made only worse by the failure of the 1918–19 monsoon and by profiteering and speculation.[181] The global influenza epidemic and the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 added to the general jitters; the former among the population already experiencing economic woes,[182] and the latter among government officials, fearing a similar revolution in India.[183]

To combat what it saw as a coming crisis, the government now drafted the Rowlatt committee's recommendations into two Rowlatt Bills.[176] Although the bills were authorised for legislative consideration by Edwin Montagu, they were done so unwillingly, with the accompanying declaration, "I loathe the suggestion at first sight of preserving the Defence of India Act in peacetime to such an extent as Rowlatt and his friends think necessary."[179] In the ensuing discussion and vote in the Imperial Legislative Council, all Indian members voiced opposition to the bills. The Government of India was, nevertheless, able to use of its "official majority" to ensure passage of the bills early in 1919.[179] However, what it passed, in deference to the Indian opposition, was a lesser version of the first bill, which now allowed extrajudicial powers, but for a period of exactly three years and for the prosecution solely of "anarchical and revolutionary movements", dropping entirely the second bill involving modification the Indian Penal Code.[179] Even so, when it was passed, the new Rowlatt Act aroused widespread indignation throughout India, and brought Gandhi to the forefront of the nationalist movement.[176]

Meanwhile, Montagu and Chelmsford themselves finally presented their report in July 1918 after a long fact-finding trip through India the previous winter.[184] After more discussion by the government and parliament in Britain, and another tour by the Franchise and Functions Committee for the purpose of identifying who among the Indian population could vote in future elections, the Government of India Act 1919 (also known as the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms) was passed in December 1919.[184] The new Act enlarged both the provincial and Imperial legislative councils and repealed the Government of India's recourse to the "official majority" in unfavourable votes.[184] Although departments like defence, foreign affairs, criminal law, communications, and income-tax were retained by the Viceroy and the central government in New Delhi, other departments like public health, education, land-revenue, local self-government were transferred to the provinces.[184] The provinces themselves were now to be administered under a new dyarchical system, whereby some areas like education, agriculture, infrastructure development, and local self-government became the preserve of Indian ministers and legislatures, and ultimately the Indian electorates, while others like irrigation, land-revenue, police, prisons, and control of media remained within the purview of the British governor and his executive council.[184] The new Act also made it easier for Indians to be admitted into the civil service and the army officer corps.

A greater number of Indians were now enfranchised, although, for voting at the national level, they constituted only 10% of the total adult male population, many of whom were still illiterate.[184] In the provincial legislatures, the British continued to exercise some control by setting aside seats for special interests they considered cooperative or useful. In particular, rural candidates, generally sympathetic to British rule and less confrontational, were assigned more seats than their urban counterparts.[184] Seats were also reserved for non-Brahmins, landowners, businessmen, and college graduates. The principal of "communal representation", an integral part of the Minto-Morley Reforms, and more recently of the Congress-Muslim League Lucknow Pact, was reaffirmed, with seats being reserved for Muslims, Sikhs, Indian Christians, Anglo-Indians, and domiciled Europeans, in both provincial and Imperial legislative councils.[184] The Montagu-Chelmsford reforms offered Indians the most significant opportunity yet for exercising legislative power, especially at the provincial level; however, that opportunity was also restricted by the still limited number of eligible voters, by the small budgets available to provincial legislatures, and by the presence of rural and special interest seats that were seen as instruments of British control.[184] Its scope was unsatisfactory to the Indian political leadership, famously expressed by Annie Beasant as something "unworthy of England to offer and India to accept".[185][citation not found]

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre or "Amritsar massacre", took place in the Jallianwala Bagh public garden in the predominantly Sikh northern city of Amritsar. After days of unrest Brigadier-General Reginald E.H. Dyer forbade public meetings and on Sunday 13 April 1919 fifty British Indian Army soldiers commanded by Dyer began shooting at an unarmed gathering of thousands of men, women, and children without warning. Casualty estimates vary widely, with the Government of India reporting 379 dead, with 1,100 wounded.[186] The Indian National Congress estimated three times the number of dead. Dyer was removed from duty but he became a celebrated hero in Britain among people with connections to the Raj.[187] Historians consider the episode was a decisive step towards the end of British rule in India.[188]

In 1920, after the British government refused to back down, Gandhi began his campaign of non-cooperation,

prompting many Indians to return British awards and honours, to resign

from civil service, and to again boycott British goods. In addition,

Gandhi reorganised the Congress, transforming it into a mass movement

and opening its membership to even the poorest Indians. Although Gandhi

halted the non-cooperation movement in 1922 after the violent incident at Chauri Chaura, the movement revived again, in the mid-1920s.

The visit, in 1928, of the British Simon Commission, charged with instituting constitutional reform in India, resulted in widespread protests throughout the country.[189] Earlier, in 1925, non-violent protests of the Congress had resumed too, this time in Gujarat, and led by Patel, who organised farmers to refuse payment of increased land taxes; the success of this protest, the Bardoli Satyagraha, brought Gandhi back into the fold of active politics.[189]

At its annual session in Lahore, the Indian National Congress, under the presidency of Jawaharlal Nehru, issued a demand for Purna Swaraj (Hindustani language: "complete independence"), or Purna Swarajya. The declaration was drafted by the Congress Working Committee, which included Gandhi, Nehru, Patel, and Chakravarthi Rajagopalachari. Gandhi subsequently led an expanded movement of civil disobedience, culminating in 1930 with the Salt Satyagraha,

in which thousands of Indians defied the tax on salt, by marching to

the sea and making their own salt by evaporating seawater. Although,

many, including Gandhi, were arrested, the British government eventually

gave in, and in 1931 Gandhi travelled to London to negotiate new reform

at the Round Table Conferences.

In local terms, British control rested on the Indian Civil Service, but it faced growing difficulties. Fewer and fewer young men in Britain were interested in joining, and the continuing distrust of Indians resulted in a declining base in terms of quality and quantity. By 1945 Indians were numerically dominant in the ICS and at issue was loyal divided between the Empire and independence.[190] The finances of the Raj depended on land taxes, and these became problematic in the 1930s. Epstein argues that after 1919 it became harder and harder to collect the land revenue. The Raj's suppression of civil disobedience after 1934 temporarily increased the power of the revenue agents but after 1937 they were forced by the new Congress-controlled provincial governments to hand back confiscated land. Again the outbreak of war strengthened them, in the face of the Quit India movement the revenue collectors had to rely on military force and by 1946–47 direct British control was rapidly disappearing in much of the countryside.[191]

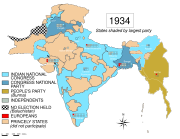

In 1935, after the Round Table Conferences, Parliament passed the Government of India Act 1935, which authorised the establishment of independent legislative assemblies in all provinces of British India, the creation of a central government incorporating both the British provinces and the princely states, and the protection of Muslim minorities. The future Constitution of independent India was based on this act.[192] However, it divided the electorate into 19 religious and social categories, e.g., Muslims, Sikhs, Indian Christians, Depressed Classes, Landholders, Commerce and Industry, Europeans, Anglo-Indians, etc., each of which was given separate representation in the Provincial Legislative Assemblies. A voter could cast a vote only for candidates in his own category.

The 1935 Act provided for more autonomy for Indian provinces, with the goal of cooling off nationalist sentiment. The act provided for a national parliament and an executive branch under the purview of the British government, but the rulers of the princely states managed to block its implementation. These states remained under the full control of their hereditary rulers, with no popular government. To prepare for elections Congress built up its grass roots membership from 473,000 in 1935 to 4.5 million in 1939.[193]

In the 1937 elections Congress won victories in seven of the eleven provinces of British India.[194] Congress governments, with wide powers, were formed in these provinces. The widespread voter support for the Indian National Congress surprised Raj officials, who previously had seen the Congress as a small elitist body.[195]

While the Muslim League was a small elite group in 1927 with only

1300 members, it grew rapidly once it became an organisation that

reached out to the masses, reaching 500,000 members in Bengal in 1944,

200,000 in Punjab, and hundreds of thousands elsewhere.[196] Jinnah now was well positioned to negotiate with the British from a position of power.[197] With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the viceroy, Lord Linlithgow,

declared war on India's behalf without consulting Indian leaders,

leading the Congress provincial ministries to resign in protest. The

Muslim League, in contrast, supported Britain in the war effort and

maintained its control of the government in three major provinces,

Bengal, Sind and the Punjab.[198]

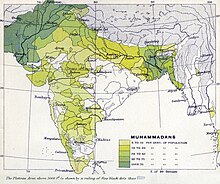

Jinnah repeatedly warned that Muslims would be unfairly treated in an independent India dominated by the Congress. On 24 March 1940 in Lahore, the League passed the "Lahore Resolution", demanding that, "the areas in which the Muslims are numerically in majority as in the North-Western and Eastern zones of India should be grouped to constitute independent states in which the constituent units shall be autonomous and sovereign." Although there were other important national Muslim politicians such as Congress leader Ab'ul Kalam Azad, and influential regional Muslim politicians such as A. K. Fazlul Huq of the leftist Krishak Praja Party in Bengal, Sikander Hyat Khan of the landlord-dominated Punjab Unionist Party, and Abd al-Ghaffar Khan of the pro-Congress Khudai Khidmatgar (popularly, "red shirts") in the North West Frontier Province, the British, over the next six years, were to increasingly see the League as the main representative of Muslim India.[199]

The Congress was secular and strongly opposed having any religious state.[196] It insisted there was a natural unity to India, and repeatedly blamed the British for "divide and rule" tactics based on prompting Muslims to think of themselves as alien from Hindus. Jinnah rejected the notion of a united India, and emphasised that religious communities were more basic than an artificial nationalism. He proclaimed the Two-Nation Theory,[200] stating at Lahore on 22 March 1940:

London paid most of the cost of the Indian Army, which had the effect of erasing India's national debt. It ended the war with a surplus of £1,300 million. In addition, heavy British spending on munitions produced in India (such as uniforms, rifles, machine-guns, field artillery, and ammunition) led to a rapid expansion of industrial output, such as textiles (up 16%), steel (up 18%), chemicals (up 30%). Small warships were built, and an aircraft factory opened in Bangalore. The railway system, with 700,000 employees, was taxed to the limit as demand for transportation soared.[205]

The British government sent the Cripps' mission

in 1942 to secure Indian nationalists' co-operation in the war effort

in exchange for a promise of independence as soon as the war ended. Top

officials in Britain, most notably Prime Minister Winston Churchill, did not support the Cripps Mission and negotiations with the Congress soon broke down.[206]

Congress launched the "Quit India" movement in July 1942 demanding the immediate withdrawal of the British from India or face nationwide civil disobedience. On 8 August the Raj arrested all national, provincial and local Congress leaders, holding tens of thousands of them until 1945. The country erupted in violent demonstrations led by students and later by peasant political groups, especially in Eastern United Provinces, Bihar, and western Bengal. The large wartime British Army presence crushed the movement in a little more than six weeks;[207] nonetheless, a portion of the movement formed for a time an underground provisional government on the border with Nepal.[207] In other parts of India, the movement was less spontaneous and the protest less intensive, however it lasted sporadically into the summer of 1943. It did not slow down the British war effort or recruiting for the army.[208]

Earlier, Subhas Chandra Bose, who had been a leader of the younger, radical, wing of the Indian National Congress in the late 1920s and 1930s, had risen to become Congress President from 1938 to 1939.[209] However, he was ousted from the Congress in 1939 following differences with the high command,[210] and subsequently placed under house arrest by the British before escaping from India in early 1941.[211] He turned to Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan for help in gaining India's independence by force.[212] With Japanese support, he organised the Indian National Army, composed largely of Indian soldiers of the British Indian army who had been captured by the Japanese in the Battle of Singapore. As the war turned against them, the Japanese came to support a number of puppet and provisional governments in the captured regions, including those in Burma, the Philippines and Vietnam, and in addition, the Provisional Government of Azad Hind, presided by Bose.[212]

Bose's effort, however, was short lived. In mid-1944 the British army first halted and then reversed the Japanese U-Go offensive, beginning the successful part of the Burma Campaign. Bose's Indian National Army largely disintegrated during the subsequent fighting in Burma, with its remaining elements surrendering with the recapture of Singapore in September 1945. Bose died in August from third degree burns received after attempting to escape in an overloaded Japanese plane which crashed in Taiwan,[213] which many Indians believe did not happen.[214][215][216] Although Bose was unsuccessful, he roused patriotic feelings in India.[217]

In January 1946, a number of mutinies broke out in the armed

services, starting with that of RAF servicemen frustrated with their

slow repatriation to Britain.[218] The mutinies came to a head with mutiny of the Royal Indian Navy

in Bombay in February 1946, followed by others in Calcutta, Madras, and

Karachi. Although the mutinies were rapidly suppressed, they had the

effect of spurring the new Labour government in Britain to action, and

leading to the Cabinet Mission to India led by the Secretary of State

for India, Lord Pethick Lawrence, and including Sir Stafford Cripps, who had visited four years before.[218]

Also in early 1946, new elections were called in India. Earlier, at the end of the war in 1945, the colonial government had announced the public trial of three senior officers of Bose's defeated Indian National Army who stood accused of treason. Now as the trials began, the Congress leadership, although ambivalent towards the INA, chose to defend the accused officers.[219] The subsequent convictions of the officers, the public outcry against the convictions, and the eventual remission of the sentences, created positive propaganda for the Congress, which only helped in the party's subsequent electoral victories in eight of the eleven provinces.[220] The negotiations between the Congress and the Muslim League, however, stumbled over the issue of the partition. Jinnah proclaimed 16 August 1946, Direct Action Day, with the stated goal of highlighting, peacefully, the demand for a Muslim homeland in British India. The following day Hindu-Muslim riots broke out in Calcutta and quickly spread throughout British India. Although the Government of India and the Congress were both shaken by the course of events, in September, a Congress-led interim government was installed, with Jawaharlal Nehru as united India's prime minister.[221]

Later that year, the Labour

government in Britain, its exchequer exhausted by the recently

concluded World War II, and conscious that it had neither the mandate at

home, the international support, nor the reliability of native forces for continuing to control an increasingly restless British India,[222]

The great majority of Indians remained in place with independence, but in border areas millions of people (Muslim, Sikh, and Hindu) relocated across the newly drawn borders. In Punjab, where the new border lines divided the Sikh regions in half, there was much bloodshed; in Bengal and Bihar, where Gandhi's presence assuaged communal tempers, the violence was more limited. In all, somewhere between 250,000 and 500,000 people on both sides of the new borders, among both the refugee and resident populations of the three faiths, died in the violence.[227] Other estimates of the number of deaths are as high as 1,500,000.[228]

The only other emperor during this period, Edward VIII, 1938, did not issue any Indian currency under his name.

Interpretation Act 1889 (52 & 53 Vict. c. 63), s. 18.

Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition, 1989: from Skr. rāj: to reign, rule; cognate with L. rēx, rēg-is, OIr. rī, rīg king (see RICH).

Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd edition (June 2008), on-line edition (September 2011): "spec. In full British Raj. Direct rule in India by the British (1858–1947); this period of dominion."

Stein, Burton (2010), A History of India, John Wiley & Sons, p. 107, ISBN 978-1-4443-2351-1 Quote: "When the formal rule of the Company was replaced by the direct rule of the British Crown in 1858, ...."

Lowe, Lisa (2015), The Intimacies of Four Continents, Duke University Press, p. 71, ISBN 978-0-8223-7564-7

Quote: "... Company rule in India lasted effectively from the Battle of

Plassey in 1757 until 1858, when following the 1857 Indian Rebellion,

the British Crown assumed direct colonial rule of India in the new

British Raj."

Wright, Edmund (2015), A Dictionary of World History, Oxford University Press, p. 537, ISBN 978-0-19-968569-1 Quote:"More than 500 Indian kingdoms and principalities ... existed during the "British Raj" period (1858–1947)"

Fair, C. Christine (2014), Fighting to the End: The Pakistan Army's Way of War, Oxford University Press, p. 61, ISBN 978-0-19-989270-9 Quote: "... by 1909 the Government of India, reflecting on 50 years of Crown rule after the rebellion, could boast that ..."

Glanville, Luke (2013), Sovereignty and the Responsibility to Protect: A New History, University of Chicago Press, p. 120, ISBN 978-0-226-07708-6

Quote:"Mill, who was himself employed by the British East India company

from the age of seventeen until the British government assumed direct

rule over India in 1858."

Morefield, Jeanne (2014), Empires Without Imperialism: Anglo-American Decline and the Politics of Deflection, Oxford University Press, p. 189, ISBN 978-0-19-938725-0

Quote: "The 'Indian Empire' was a name given to those areas in the

Indian subcontinent both directly and indirectly ruled by Britain after

the rebellion; the British issued passports after 1876 under that name."

Bowen, H. V.; Mancke, Elizabeth; Reid, John G. (2012), Britain's Oceanic Empire: Atlantic and Indian Ocean Worlds, C.1550–1850, Cambridge University Press, p. 106, ISBN 978-1-107-02014-6 Quote: "British India, meanwhile, was itself the powerful 'metropolis' of its own colonial empire, 'the Indian empire'."