- This particular answer says 55 million deaths during the Cold War. However, I have also heard estimates as high a 100 million. The problem is that this was about a 50 year period so those who survived the first part and were wounded likely might not have survived to the second part because it was so very long a time. For example, I was born in 1948, hid under my desk during the 1950s as a child as we were told by our public school teachers, watched people my age die in Viet Nam on TV every night on the news(sickening). And by the time it was over I was over 40 years old in 1990.

- The Cold War was a state of political and military tension after World War II between powers in the Western Bloc (the United States, its NATO allies and others) and ...

For other uses, see Cold War (disambiguation).

Photograph of the Berlin Wall

taken from the West side. The Wall was built in 1961 to prevent East

Germans from fleeing and to stop an economically disastrous drain of

workers. It was a symbol of the Cold War and its fall in 1989 marked the

approaching end of the war.

Historians do not fully agree on the dates, but 1947–91 is common. The term "cold" is used because there was no large-scale fighting directly between the two sides, although there were major regional wars, known as proxy wars, supported by the two sides. The Cold War split the temporary wartime alliance against Nazi Germany, leaving the USSR and the US as two superpowers with profound economic and political differences: the former being a single-party Marxist–Leninist state operating a planned economy and controlled press and owning exclusively the right to establish and govern communities, and the latter being a capitalist state with generally free elections and press, which also granted freedom of expression and freedom of association to its citizens. A self-proclaimed neutral bloc arose with the Non-Aligned Movement founded by Egypt, India, Indonesia and Yugoslavia; this faction rejected association with either the US-led West or the Soviet-led East. The two superpowers never engaged directly in full-scale armed combat, but they were heavily armed in preparation for a possible all-out nuclear world war. Each side had a nuclear deterrent that deterred an attack by the other side, on the basis that such an attack would lead to total destruction of the attacker: the doctrine of mutually assured destruction (MAD). Aside from the development of the two sides' nuclear arsenals, and deployment of conventional military forces, the struggle for dominance was expressed via proxy wars around the globe, psychological warfare, massive propaganda campaigns and espionage, rivalry at sports events, and technological competitions such as the Space Race.

The first phase of the Cold War began in the first two years after the end of the Second World War in 1945. The USSR consolidated its control over the states of the Eastern Bloc, while the United States began a strategy of global containment to challenge Soviet power, extending military and financial aid to the countries of Western Europe (for example, supporting the anti-communist side in the Greek Civil War) and creating the NATO alliance. The Berlin Blockade (1948–49) was the first major crisis of the Cold War. With victory of the communist side in the Chinese Civil War and the outbreak of the Korean War (1950–53), the conflict expanded. The USSR and USA competed for influence in Latin America, and the decolonizing states of Africa, the Middle East and Southeast Asia. Meanwhile, the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 was stopped by the Soviets. The expansion and escalation sparked more crises, such as the Suez Crisis (1956), the Berlin Crisis of 1961, and the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. Following the Cuban missile crisis, a new phase began that saw the Sino-Soviet split complicate relations within the communist sphere, while US allies, particularly France, demonstrated greater independence of action. The USSR crushed the 1968 Prague Spring liberalization program in Czechoslovakia, and the Vietnam War (1955–75) ended with a defeat of the US-backed Republic of South Vietnam, prompting further adjustments.

By the 1970s, both sides had become interested in accommodations to create a more stable and predictable international system, inaugurating a period of détente that saw Strategic Arms Limitation Talks and the US opening relations with the People's Republic of China as a strategic counterweight to the Soviet Union. Détente collapsed at the end of the decade with the Soviet war in Afghanistan beginning in 1979. The early 1980s were another period of elevated tension, with the Soviet downing of Korean Air Lines Flight 007 (1983), and the "Able Archer" NATO military exercises (1983). The United States increased diplomatic, military, and economic pressures on the Soviet Union, at a time when the communist state was already suffering from economic stagnation. In the mid-1980s, the new Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev introduced the liberalizing reforms of perestroika ("reorganization", 1987) and glasnost ("openness", c. 1985) and ended Soviet involvement in Afghanistan. Pressures for national independence grew stronger in Eastern Europe, especially Poland. Gorbachev meanwhile refused to use Soviet troops to bolster the faltering Warsaw Pact regimes as had occurred in the past. The result in 1989 was a wave of revolutions that peacefully (with the exception of the Romanian Revolution) overthrew all of the communist regimes of Central and Eastern Europe. The Communist Party of the Soviet Union itself lost control and was banned following an abortive coup attempt in August 1991. This in turn led to the formal dissolution of the USSR in December 1991 and the collapse of communist regimes in other countries such as Mongolia, Cambodia and South Yemen. The United States remained as the world's only superpower.

The Cold War and its events have left a significant legacy. It is often referred to in popular culture, especially in media featuring themes of espionage (e.g. the internationally successful James Bond movie franchise) and the threat of nuclear warfare.

Contents

- 1 Origins of the term

- 2 Background

- 3 End of World War II (1945–47)

- 4 Beginnings of the Cold War (1947–53)

- 5 Crisis and escalation (1953–62)

- 5.1 Khrushchev, Eisenhower and de-Stalinization

- 5.2 Warsaw Pact and Hungarian Revolution

- 5.3 Berlin Ultimatum and European integration

- 5.4 Competition in the Third World

- 5.5 Sino-Soviet split

- 5.6 Space race

- 5.7 Cuban Revolution and the Bay of Pigs Invasion

- 5.8 Berlin Crisis of 1961

- 5.9 Cuban Missile Crisis and Khrushchev ouster

- 6 Confrontation through détente (1962–79)

- 7 "Second Cold War" (1979–85)

- 8 Final years (1985–91)

- 9 Aftermath

- 10 Historiography

- 11 See also

- 12 Footnotes

- 13 References and further reading

- 14 External links

Origins of the term

At the end of World War II, English writer George Orwell used cold war, as a general term, in his essay "You and the Atomic Bomb", published 19 October 1945 in the British newspaper Tribune. Contemplating a world living in the shadow of the threat of nuclear warfare, Orwell looked at James Burnham's predictions of a polarized world, writing:- Looking at the world as a whole, the drift for many decades has been not towards anarchy but towards the reimposition of slavery....James Burnham's theory has been much discussed, but few people have yet considered its ideological implications—that is, the kind of world-view, the kind of beliefs, and the social structure that would probably prevail in a state which was at once unconquerable and in a permanent state of "cold war" with its neighbours.[1]

The first use of the term to describe the specific post-war geopolitical confrontation between the USSR and the United States came in a speech by Bernard Baruch, an influential advisor to Democratic presidents,[3] on 16 April 1947. The speech, written by journalist Herbert Bayard Swope,[4] proclaimed, "Let us not be deceived: we are today in the midst of a cold war."[5] Newspaper columnist Walter Lippmann gave the term wide currency with his book The Cold War; when asked in 1947 about the source of the term, Lippmann traced it to a French term from the 1930s, la guerre froide.[6]

Background

Main article: Origins of the Cold War

Various events before the Second World War demonstrated the mutual distrust and suspicion between the Western powers and the Soviet Union, apart from the general philosophical challenge the communists made towards capitalism.[10] There was Western support of the anti-Bolshevik White movement in the Russian Civil War,[7] the 1926 Soviet funding of a British general workers strike causing Britain to break relations with the Soviet Union,[11] Stalin's 1927 declaration of peaceful coexistence with capitalist countries "receding into the past,"[12] conspiratorial allegations during the 1928 Shakhty show trial of a planned British- and French-led coup d'état,[13] the American refusal to recognize the Soviet Union until 1933[14] and the Stalinist Moscow Trials of the Great Purge, with allegations of British, French, Japanese and Nazi German espionage.[15] However, both the US and USSR were generally isolationist between the two world wars.[16]

The Soviet Union initially signed a non-aggression pact with Germany. But after the German Army invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941 and the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the Soviet Union and the Allied powers formed an alliance of convenience. Britain signed a formal alliance and the United States made an informal agreement. In wartime, the United States supplied both Britain and the Soviets through its Lend-Lease Program.[17] However, Stalin remained highly suspicious and believed that the British and the Americans had conspired to ensure the Soviets bore the brunt of the fighting against Nazi Germany. According to this view, the Western Allies had deliberately delayed opening a second anti-German front in order to step in at the last moment and shape the peace settlement. Thus, Soviet perceptions of the West left a strong undercurrent of tension and hostility between the Allied powers.[18]

End of World War II (1945–47)

Wartime conferences regarding post-war Europe

Further information: Tehran Conference and Yalta Conference

The "Big Three" at the Yalta Conference: Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin, 1945.

The Soviet Union sought to dominate the internal affairs of countries that bordered it.[19][21] During the war, Stalin had created special training centers for communists from different countries so that they could set up secret police forces loyal to Moscow as soon as the Red Army took control. Soviet agents took control of the media, especially radio; they quickly harassed and then banned all independent civic institutions, from youth groups to schools, churches and rival political parties.[22] Stalin also sought continued peace with Britain and the United States, hoping to focus on internal reconstruction and economic growth.[23]

The Western Allies were divided in their vision of the new post-war world. Roosevelt's goals – military victory in both Europe and Asia, the achievement of global American economic supremacy over the British Empire, and the creation of a world peace organization – were more global than Churchill's, which were mainly centered on securing control over the Mediterranean, ensuring the survival of the British Empire, and the independence of Central and Eastern European countries as a buffer between the Soviets and the United Kingdom.[24]

In the American view, Stalin seemed a potential ally in accomplishing their goals, whereas in the British approach Stalin appeared as the greatest threat to the fulfillment of their agenda. With the Soviets already occupying most of Central and Eastern Europe, Stalin was at an advantage and the two western leaders vied for his favors. The differences between Roosevelt and Churchill led to several separate deals with the Soviets. In October 1944, Churchill traveled to Moscow and agreed to divide the Balkans into respective spheres of influence, and at Yalta Roosevelt signed a separate deal with Stalin in regard of Asia and refused to support Churchill on the issues of Poland and the Reparations.[24]

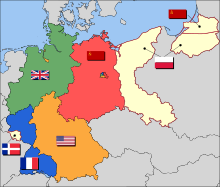

Post-war Allied occupation zones in Germany.

Following the Allies' May 1945 victory, the Soviets effectively occupied Central and Eastern Europe,[25] while strong US and Western allied forces remained in Western Europe. In Allied-occupied Germany, the Soviet Union, United States, Britain and France established zones of occupation and a loose framework for parceled four-power control.[27]

The 1945 Allied conference in San Francisco established the multi-national United Nations (UN) for the maintenance of world peace, but the enforcement capacity of its Security Council was effectively paralyzed by individual members' ability to use veto power.[28] Accordingly, the UN was essentially converted into an inactive forum for exchanging polemical rhetoric, and the Soviets regarded it almost exclusively as a propaganda tribune.[29]

Potsdam Conference and defeat of Japan

Further information: Potsdam Conference and Surrender of Japan

At the Potsdam Conference,

which started in late July after Germany's surrender, serious

differences emerged over the future development of Germany and the rest

of Central and Eastern Europe.[30]

Moreover, the participants' mounting antipathy and bellicose language

served to confirm their suspicions about each other's hostile intentions

and entrench their positions.[31] At this conference Truman informed Stalin that the United States possessed a powerful new weapon.[32]Stalin was aware that the Americans were working on the atomic bomb and, given that the Soviets' own rival program was in place, he reacted to the news calmly. The Soviet leader said he was pleased by the news and expressed the hope that the weapon would be used against Japan.[32] One week after the end of the Potsdam Conference, the US bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Shortly after the attacks, Stalin protested to US officials when Truman offered the Soviets little real influence in occupied Japan.[33]

Beginnings of the Eastern Bloc

Further information: Eastern Bloc

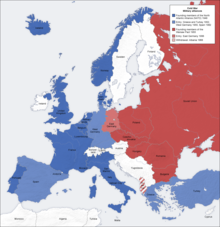

Post-war territorial changes in Europe and the formation of the Eastern Bloc, the so-called 'Iron Curtain'.

The Central and Eastern European territories liberated from the Nazis and occupied by the Soviet armed forces were added to the Eastern Bloc by converting them into satellite states,[39] such as East Germany,[40] the People's Republic of Poland, the People's Republic of Bulgaria, the People's Republic of Hungary,[41] the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic,[42] the People's Republic of Romania and the People's Republic of Albania.[43]

The Soviet-style regimes that arose in the Bloc not only reproduced Soviet command economies, but also adopted the brutal methods employed by Joseph Stalin and Soviet secret police to suppress real and potential opposition.[44] In Asia, the Red Army had overrun Manchuria in the last month of the war, and went on to occupy the large swathe of Korean territory located north of the 38th parallel.[45]

As part of consolidating Stalin's control over the Eastern Bloc, the NKVD, led by Lavrentiy Beriya, supervised the establishment of Soviet-style secret police systems in the Bloc that were supposed to crush anti-communist resistance.[46] When the slightest stirrings of independence emerged in the Bloc, Stalin's strategy matched that of dealing with domestic pre-war rivals: they were removed from power, put on trial, imprisoned, and in several instances, executed.[47]

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was concerned that, given the enormous size of Soviet forces deployed in Europe at the end of the war, and the perception that Soviet leader Joseph Stalin was unreliable, there existed a Soviet threat to Western Europe.[48]

Preparing for a "new war"

In February 1946, George F. Kennan's "Long Telegram" from Moscow helped to articulate the US government's increasingly hard line against the Soviets, and became the basis for US strategy toward the Soviet Union for the duration of the Cold War.[49] That September, the Soviet side produced the Novikov telegram, sent by the Soviet ambassador to the US but commissioned and "co-authored" by Vyacheslav Molotov; it portrayed the US as being in the grip of monopoly capitalists who were building up military capability "to prepare the conditions for winning world supremacy in a new war".[50]On 6 September 1946, James F. Byrnes delivered a speech in Germany repudiating the Morgenthau Plan (a proposal to partition and de-industrialize post-war Germany) and warning the Soviets that the US intended to maintain a military presence in Europe indefinitely.[51] As Byrnes admitted a month later, "The nub of our program was to win the German people ... it was a battle between us and Russia over minds ..."[52]

A few weeks after the release of this "Long Telegram", former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill delivered his famous "Iron Curtain" speech in Fulton, Missouri.[53] The speech called for an Anglo-American alliance against the Soviets, whom he accused of establishing an "iron curtain" from "Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic".[39][54]

Beginnings of the Cold War (1947–53)

Main article: Cold War (1947–1953)

Cominform and the Tito–Stalin split

Further information: Cominform and Tito–Stalin split

In September 1947, the Soviets created Cominform,

the purpose of which was to enforce orthodoxy within the international

communist movement and tighten political control over Soviet satellites through coordination of communist parties in the Eastern Bloc.[55] Cominform faced an embarrassing setback the following June, when the Tito–Stalin split obliged its members to expel Yugoslavia, which remained communist but adopted a non-aligned position.[56]Containment and the Truman Doctrine

Main articles: Containment and Truman Doctrine

European military alliances.

The American government's response to this announcement was the adoption of containment,[58] the goal of which was to stop the spread of communism. Truman delivered a speech that called for the allocation of $400 million to intervene in the war and unveiled the Truman Doctrine, which framed the conflict as a contest between free peoples and totalitarian regimes.[58] Even though the insurgents were helped by Josip Broz Tito's Yugoslavia,[14] US policymakers accused the Soviet Union of conspiring against the Greek royalists in an effort to expand Soviet influence.[59]

Enunciation of the Truman Doctrine marked the beginning of a US bipartisan defense and foreign policy consensus between Republicans and Democrats focused on containment and deterrence that weakened during and after the Vietnam War, but ultimately persisted thereafter.[60][61] Moderate and conservative parties in Europe, as well as social democrats, gave virtually unconditional support to the Western alliance,[62] while European and American communists, paid by the KGB and involved in its intelligence operations,[63] adhered to Moscow's line, although dissent began to appear after 1956. Other critiques of consensus politics came from anti-Vietnam War activists, the CND and the nuclear freeze movement.[64]

Marshall Plan and Czechoslovak coup d'état

Map of Cold-War era Europe and the Near East showing countries that received Marshall Plan aid. The red columns show the relative amount of total aid received per nation.

European economic alliances

The plan's aim was to rebuild the democratic and economic systems of Europe and to counter perceived threats to Europe's balance of power, such as communist parties seizing control through revolutions or elections.[66] The plan also stated that European prosperity was contingent upon German economic recovery.[67] One month later, Truman signed the National Security Act of 1947, creating a unified Department of Defense, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and the National Security Council (NSC). These would become the main bureaucracies for US policy in the Cold War.[68]

Stalin believed that economic integration with the West would allow Eastern Bloc countries to escape Soviet control, and that the US was trying to buy a pro-US re-alignment of Europe.[55] Stalin therefore prevented Eastern Bloc nations from receiving Marshall Plan aid.[55] The Soviet Union's alternative to the Marshall plan, which was purported to involve Soviet subsidies and trade with central and eastern Europe, became known as the Molotov Plan (later institutionalized in January 1949 as the Comecon).[14] Stalin was also fearful of a reconstituted Germany; his vision of a post-war Germany did not include the ability to rearm or pose any kind of threat to the Soviet Union.[69]

In early 1948, following reports of strengthening "reactionary elements", Soviet operatives executed a coup d'état in Czechoslovakia, the only Eastern Bloc state that the Soviets had permitted to retain democratic structures.[70][71] The public brutality of the coup shocked Western powers more than any event up to that point, set in a motion a brief scare that war would occur and swept away the last vestiges of opposition to the Marshall Plan in the United States Congress.[72]

The twin policies of the Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan led to billions in economic and military aid for Western Europe, Greece, and Turkey. With US assistance, the Greek military won its civil war.[68] Under the leadership of Alcide De Gasperi the Italian Christian Democrats defeated the powerful Communist-Socialist alliance in the elections of 1948.[73] At the same time there was increased intelligence and espionage activity, Eastern Bloc defections and diplomatic expulsions.[74]

Berlin Blockade and airlift

C-47s unloading at Tempelhof Airport in Berlin during the Berlin Blockade.

Main article: Berlin Blockade

The United States and Britain merged their western German occupation zones into "Bizonia" (1 January 1947, later "Trizonia" with the addition of France's zone, April 1949).[75]

As part of the economic rebuilding of Germany, in early 1948,

representatives of a number of Western European governments and the

United States announced an agreement for a merger of western German

areas into a federal governmental system.[76] In addition, in accordance with the Marshall Plan, they began to re-industrialize and rebuild the German economy, including the introduction of a new Deutsche Mark currency to replace the old Reichsmark currency that the Soviets had debased.[77]Shortly thereafter, Stalin instituted the Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949), one of the first major crises of the Cold War, preventing food, materials and supplies from arriving in West Berlin.[78] The United States, Britain, France, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and several other countries began the massive "Berlin airlift", supplying West Berlin with food and other provisions.[79]

The Soviets mounted a public relations campaign against the policy change. Once again the East Berlin communists attempted to disrupt the Berlin municipal elections (as they had done in the 1946 elections),[75] which were held on 5 December 1948 and produced a turnout of 86.3% and an overwhelming victory for the non-communist parties.[80] The results effectively divided the city into East and West versions of its former self. 300,000 Berliners demonstrated and urged the international airlift to continue,[81] and US Air Force pilot Gail Halvorsen created "Operation Vittles", which supplied candy to German children.[82] In May 1949, Stalin backed down and lifted the blockade.[46][83]

In 1952, Stalin repeatedly proposed a plan to unify East and West Germany under a single government chosen in elections supervised by the United Nations if the new Germany were to stay out of Western military alliances, but this proposal was turned down by the Western powers. Some sources dispute the sincerity of the proposal.[84]

NATO beginnings and Radio Free Europe

President Truman signs the National Security Act Amendment of 1949 with guests in the Oval Office.

Media in the Eastern Bloc was an organ of the state, completely reliant on and subservient to the communist party, with radio and television organizations being state-owned, while print media was usually owned by political organizations, mostly by the local communist party.[87] Soviet propaganda used Marxist philosophy to attack capitalism, claiming labor exploitation and war-mongering imperialism were inherent in the system.[88]

Along with the broadcasts of the British Broadcasting Corporation and the Voice of America to Central and Eastern Europe,[89] a major propaganda effort begun in 1949 was Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, dedicated to bringing about the peaceful demise of the communist system in the Eastern Bloc.[90] Radio Free Europe attempted to achieve these goals by serving as a surrogate home radio station, an alternative to the controlled and party-dominated domestic press.[90] Radio Free Europe was a product of some of the most prominent architects of America's early Cold War strategy, especially those who believed that the Cold War would eventually be fought by political rather than military means, such as George F. Kennan.[91]

American policymakers, including Kennan and John Foster Dulles, acknowledged that the Cold War was in its essence a war of ideas.[91] The United States, acting through the CIA, funded a long list of projects to counter the communist appeal among intellectuals in Europe and the developing world.[92] The CIA also covertly sponsored a domestic propaganda campaign called Crusade for Freedom.[93]

In the early 1950s, the US worked for the rearmament of West Germany and, in 1955, secured its full membership of NATO.[30] In May 1953, Beria, by then in a government post, had made an unsuccessful proposal to allow the reunification of a neutral Germany to prevent West Germany's incorporation into NATO.[94]

Chinese Civil War and SEATO

Further information: Chinese Civil War and Southeast Asia Treaty Organization

Mao Zedong and Joseph Stalin in Moscow, December 1949

Chiang and his KMT government retreated to the island of Taiwan. Confronted with the communist revolution in China and the end of the American atomic monopoly in 1949, the Truman administration quickly moved to escalate and expand the containment policy.[14] In NSC-68, a secret 1950 document,[97] the National Security Council proposed to reinforce pro-Western alliance systems and quadruple spending on defense.[14]

United States officials moved thereafter to expand containment into Asia, Africa, and Latin America, in order to counter revolutionary nationalist movements, often led by communist parties financed by the USSR, fighting against the restoration of Europe's colonial empires in South-East Asia and elsewhere.[98] In the early 1950s (a period sometimes known as the "Pactomania"), the US formalized a series of alliances with Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Thailand and the Philippines (notably ANZUS in 1951 and SEATO in 1954), thereby guaranteeing the United States a number of long-term military bases.[30]

Korean War

Main article: Korean War

One of the more significant impacts of containment was the outbreak of the Korean War. In June 1950, Kim Il-sung's North Korean People's Army invaded South Korea.[99] Joseph Stalin "planned, prepared, and initiated" the invasion,[100] creating "detailed [war] plans" that were communicated to the North Koreans.[101][102][103][104] To Stalin's surprise,[14] the UN Security Council backed the defense of South Korea, though the Soviets were then boycotting meetings in protest that Taiwan and not Communist China held a permanent seat on the Council.[105] A UN force

of personnel from South Korea, the United States, the United Kingdom,

Turkey, Canada, Colombia, Australia, France, South Africa, the

Philippines, the Netherlands, Belgium, New Zealand and other countries

joined to stop the invasion.[106]

General Douglas MacArthur, UN Command CiC (seated), observes the naval shelling of Incheon from the USS Mt. McKinley, September 15, 1950.

Even though the Chinese and North Koreans were exhausted by the war and were prepared to end it by late 1952, Stalin insisted that they continue fighting, and the Armistice was approved only in July 1953, after Stalin's death.[30] North Korean leader Kim Il Sung created a highly centralized, totalitarian dictatorship – which continues to date – according himself unlimited power and generating a formidable cult of personality.[109][110] In the South, the American-backed strongman Syngman Rhee ran a significantly less brutal but deeply corrupt and authoritarian regime.[111] After Rhee was overthrown in 1960, South Korea fell within a year under a period of military rule that lasted until the re-establishment of a multi-party system in the late 1980s.

Crisis and escalation (1953–62)

Main article: Cold War (1953–1962)

NATO and Warsaw Pact troop strengths in Europe in 1959

Khrushchev, Eisenhower and de-Stalinization

In 1953, changes in political leadership on both sides shifted the dynamic of the Cold War.[112] Dwight D. Eisenhower was inaugurated president that January. During the last 18 months of the Truman administration, the American defense budget had quadrupled, and Eisenhower moved to reduce military spending by a third while continuing to fight the Cold War effectively.[14]After the death of Joseph Stalin, Nikita Khrushchev became the Soviet leader following the deposition and execution of Lavrentiy Beriya and the pushing aside of rivals Georgy Malenkov and Vyacheslav Molotov. On 25 February 1956, Khrushchev shocked delegates to the 20th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party by cataloguing and denouncing Stalin's crimes.[113] As part of a campaign of de-Stalinization, he declared that the only way to reform and move away from Stalin's policies would be to acknowledge errors made in the past.[68]

On 18 November 1956, while addressing Western ambassadors at a reception at the Polish embassy in Moscow, Khrushchev used his famous "Whether you like it or not, history is on our side. We will bury you" expression, shocking everyone present.[114] He later claimed that he had not been talking about nuclear war, but rather about the historically determined victory of communism over capitalism.[115] In 1961, Khrushchev declared that even if the USSR was behind the West, within a decade its housing shortage would disappear, consumer goods would be abundant, and within two decades, the "construction of a communist society" in the USSR would be completed "in the main".[116]

Eisenhower's secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, initiated a "New Look" for the containment strategy, calling for a greater reliance on nuclear weapons against US enemies in wartime.[68] Dulles also enunciated the doctrine of "massive retaliation", threatening a severe US response to any Soviet aggression. Possessing nuclear superiority, for example, allowed Eisenhower to face down Soviet threats to intervene in the Middle East during the 1956 Suez Crisis.[14] U.S. plans for nuclear war in the late 1950s included the "systematic destruction" of 1200 major urban centers in the Eastern Bloc and China, including Moscow, East Berlin and Beijing, with their civilian populations among the primary targets.[117]

Warsaw Pact and Hungarian Revolution

Main articles: Warsaw Pact and Hungarian Revolution of 1956

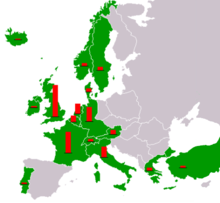

Map of the Warsaw Pact countries

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 occurred shortly after Khrushchev arranged the removal of Hungary's Stalinist leader Mátyás Rákosi.[120] In response to a popular uprising,[121] the new regime formally disbanded the secret police, declared its intention to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact and pledged to re-establish free elections. The Soviet army invaded.[122] Thousands of Hungarians were arrested, imprisoned and deported to the Soviet Union,[123] and approximately 200,000 Hungarians fled Hungary in the chaos.[124] Hungarian leader Imre Nagy and others were executed following secret trials.[125]

From 1957 through 1961, Khrushchev openly and repeatedly threatened the West with nuclear annihilation. He claimed that Soviet missile capabilities were far superior to those of the United States, capable of wiping out any American or European city. However, Khrushchev rejected Stalin's belief in the inevitability of war, and declared his new goal was to be "peaceful coexistence".[126] This formulation modified the Stalin-era Soviet stance, where international class struggle meant the two opposing camps were on an inevitable collision course where communism would triumph through global war; now, peace would allow capitalism to collapse on its own,[127] as well as giving the Soviets time to boost their military capabilities,[128] which remained for decades until Gorbachev's later "new thinking" envisioning peaceful coexistence as an end in itself rather than a form of class struggle.[129]

The events in Hungary produced ideological fractures within the communist parties of the world, particularly in Western Europe, with great decline in membership as many in both western and communist countries felt disillusioned by the brutal Soviet response.[130] The communist parties in the West would never recover from the effect the Hungarian Revolution had on their membership, a fact that was immediately recognized by some, such as the Yugoslavian politician Milovan Đilas who shortly after the revolution was crushed said that "The wound which the Hungarian Revolution inflicted on communism can never be completely healed".[130]

America's pronouncements concentrated on American strength abroad and the success of liberal capitalism.[131] However, by the late 1960s, the "battle for men's minds" between two systems of social organization that Kennedy spoke of in 1961 was largely over, with tensions henceforth based primarily on clashing geopolitical objectives rather than ideology.[132]

Berlin Ultimatum and European integration

Main article: Berlin Crisis of 1961 § Berlin ultimatum

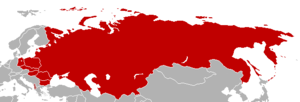

The maximum territorial extent of countries in the world under Soviet influence, after the Cuban Revolution of 1959 and before the official Sino-Soviet split of 1961

More broadly, one hallmark of the 1950s was the beginning of European integration—a fundamental by-product of the Cold War that Truman and Eisenhower promoted politically, economically, and militarily, but which later administrations viewed ambivalently, fearful that an independent Europe would forge a separate détente with the Soviet Union, which would use this to exacerbate Western disunity.[135]

Competition in the Third World

Main articles: 1953 Iranian coup d'état, 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état, Congo Crisis, Decolonization and Wars of national liberation

Nationalist movements in some countries and regions, notably Guatemala, Indonesia and Indochina were often allied with communist groups, or perceived in the West to be allied with communists.[68] In this context, the United States and the Soviet Union increasingly competed for influence by proxy in the Third World as decolonization gained momentum in the 1950s and early 1960s;[136] additionally, the Soviets saw continuing losses by imperial powers as presaging the eventual victory of their ideology.[137] Both sides were selling armaments to gain influence.[138]

1961 Soviet postage stamp demanding freedom for African nations

In Guatemala, a CIA-backed military coup ousted the left-wing President Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán in 1954.[144] The post-Arbenz government—a military junta headed by Carlos Castillo Armas—repealed a progressive land reform law, returned nationalized property belonging to the United Fruit Company, set up a National Committee of Defense Against Communism, and decreed a Preventive Penal Law Against Communism at the request of the United States.[145]

The non-aligned Indonesian government of Sukarno was faced with a major threat to its legitimacy beginning in 1956, when several regional commanders began to demand autonomy from Jakarta. After mediation failed, Sukarno took action to remove the dissident commanders. In February 1958, dissident military commanders in Central Sumatera (Colonel Ahmad Hussein) and North Sulawesi (Colonel Ventje Sumual) declared the Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia-Permesta Movement aimed at overthrowing the Sukarno regime. They were joined by many civilian politicians from the Masyumi Party, such as Sjafruddin Prawiranegara, who were opposed to the growing influence of the communist Partai Komunis Indonesia party. Due to their anti-communist rhetoric, the rebels received arms, funding, and other covert aid from the CIA until Allen Lawrence Pope, an American pilot, was shot down after a bombing raid on government-held Ambon in April 1958. The central government responded by launching airborne and seaborne military invasions of rebel strongholds Padang and Manado. By the end of 1958, the rebels were militarily defeated, and the last remaining rebel guerilla bands surrendered by August 1961.[146]

1961 Soviet stamp commemorating Patrice Lumumba, prime minister of the Republic of the Congo

In British Guiana, the leftist People's Progressive Party (PPP) candidate Cheddi Jagan won the position of chief minister in a colonially administered election in 1953, but was quickly forced to resign from power after Britain's suspension of the still-dependent nation's constitution.[148] Embarrassed by the landslide electoral victory of Jagan's allegedly Marxist party, the British imprisoned the PPP's leadership and maneuvered the organization into a divisive rupture in 1955, engineering a split between Jagan and his PPP colleagues.[149] Jagan again won the colonial elections in 1957 and 1961; despite Britain's shift to a reconsideration of its view of the left-wing Jagan as a Soviet-style communist at this time, the United States pressured the British to withhold Guyana's independence until an alternative to Jagan could be identified, supported, and brought into office.[150]

Worn down by the communist guerrilla war for Vietnamese independence and handed a watershed defeat by communist Viet Minh rebels at the 1954 Battle of Điện Biên Phủ, the French accepted a negotiated abandonment of their colonial stake in Vietnam. In the Geneva Conference, peace accords were signed, leaving Vietnam divided between a pro-Soviet administration in North Vietnam and a pro-Western administration in South Vietnam at the 17th parallel north. Between 1954 and 1961, Eisenhower's United States sent economic aid and military advisers to strengthen South Vietnam's pro-Western regime against communist efforts to destabilize it.[14]

Many emerging nations of Asia, Africa, and Latin America rejected the pressure to choose sides in the East-West competition. In 1955, at the Bandung Conference in Indonesia, dozens of Third World governments resolved to stay out of the Cold War.[151] The consensus reached at Bandung culminated with the creation of the Belgrade-headquartered Non-Aligned Movement in 1961.[68] Meanwhile, Khrushchev broadened Moscow's policy to establish ties with India and other key neutral states. Independence movements in the Third World transformed the post-war order into a more pluralistic world of decolonized African and Middle Eastern nations and of rising nationalism in Asia and Latin America.[14]

Sino-Soviet split

Main articles: Sino-Soviet split and Space Race

The period after 1956 was marked by serious setbacks for the Soviet

Union, most notably the breakdown of the Sino-Soviet alliance, beginning

the Sino-Soviet split.

Mao had defended Stalin when Khrushchev attacked him after his death in

1956, and treated the new Soviet leader as a superficial upstart,

accusing him of having lost his revolutionary edge.[152]

For his part, Khrushchev, disturbed by Mao's glib attitude toward

nuclear war, referred to the Chinese leader as a "lunatic on a throne".[153]After this, Khrushchev made many desperate attempts to reconstitute the Sino-Soviet alliance, but Mao considered it useless and denied any proposal.[152] The Chinese-Soviet animosity spilled out in an intra-communist propaganda war.[154] Further on, the Soviets focused on a bitter rivalry with Mao's China for leadership of the global communist movement.[155]

Historian Lorenz M. Lüthi argues:

- The Sino-Soviet split was one of the key events of the Cold War, equal in importance to the construction of the Berlin Wall, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Second Vietnam War, and Sino-American rapprochement. The split helped to determine the framework of the Second Cold War in general, and influenced the course of the Second Vietnam War in particular.[156]

Space race

Charting the progress of the Space Race in 1957–1975.

Cuban Revolution and the Bay of Pigs Invasion

Main articles: Cuban Revolution and Bay of Pigs Invasion

Flag of the 26 July Movement.

Diplomatic relations between Cuba and the United States continued for some time after Batista's fall, but President Eisenhower deliberately left the capital to avoid meeting Cuba's young revolutionary leader Fidel Castro during the latter's trip to Washington in April, leaving Vice President Richard Nixon to conduct the meeting in his place.[161] Cuba began negotiating arms purchases from the Eastern Bloc in March 1960.[162]

In January 1961, just prior to leaving office, Eisenhower formally severed relations with the Cuban government. In April 1961, the administration of newly elected American President John F. Kennedy mounted an unsuccessful CIA-organized ship-borne invasion of the island at Playa Girón and Playa Larga in Las Villas Province—a failure that publicly humiliated the United States.[163] Castro responded by publicly embracing Marxism–Leninism, and the Soviet Union pledged to provide further support.[163]

Berlin Crisis of 1961

Soviet and American tanks face each other at Checkpoint Charlie, on October 27, during the Berlin Crisis of 1961

The emigration resulted in a massive "brain drain" from East Germany to West Germany of younger educated professionals, such that nearly 20% of East Germany's population had migrated to West Germany by 1961.[166] That June, the Soviet Union issued a new ultimatum demanding the withdrawal of Allied forces from West Berlin.[167] The request was rebuffed, and on 13 August, East Germany erected a barbed-wire barrier that would eventually be expanded through construction into the Berlin Wall, effectively closing the loophole.[168]

Cuban Missile Crisis and Khrushchev ouster

Main articles: Cuban Project and Cuban Missile Crisis

A United States Navy P-2 of VP-18 flying over a Soviet freighter during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

In February 1962, Khrushchev learned of the American plans regarding Cuba: a "Cuban project"—approved by the CIA and stipulating the overthrow of the Cuban government in October, possibly involving the American military—and yet one more Kennedy-ordered operation to assassinate Castro.[169] Preparations to install Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba were undertaken in response.[169]

Alarmed, Kennedy considered various reactions, and ultimately responded to the installation of nuclear missiles in Cuba with a naval blockade and presented an ultimatum to the Soviets. Khrushchev backed down from a confrontation, and the Soviet Union removed the missiles in return for an American pledge not to invade Cuba again.[170] Castro later admitted that "I would have agreed to the use of nuclear weapons. ... we took it for granted that it would become a nuclear war anyway, and that we were going to disappear."[171]

The Cuban Missile Crisis (October–November 1962) brought the world closer to nuclear war than ever before.[172] The aftermath of the crisis led to the first efforts in the nuclear arms race at nuclear disarmament and improving relations,[118] although the Cold War's first arms control agreement, the Antarctic Treaty, had come into force in 1961.[173]

In 1964, Khrushchev's Kremlin colleagues managed to oust him, but allowed him a peaceful retirement.[174] Accused of rudeness and incompetence, he was also credited with ruining Soviet agriculture and bringing the world to the brink of nuclear war.[174] Khrushchev had become an international embarrassment when he authorized construction of the Berlin Wall, a public humiliation for Marxism–Leninism.[174]

Confrontation through détente (1962–79)

Main article: Cold War (1962–1979)

NATO and Warsaw Pact troop strengths in Europe in 1973

United States Navy F-4 Phantom II intercepts a Soviet Tupolev Tu-95 D aircraft in the early 1970s

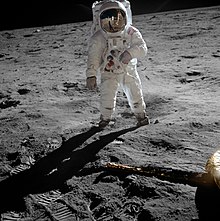

The United States reached the moon in 1969—a milestone in the space race.

As a result of the 1973 oil crisis, combined with the growing influence of Third World alignments such as the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and the Non-Aligned Movement, less-powerful countries had more room to assert their independence and often showed themselves resistant to pressure from either superpower.[98] Meanwhile, Moscow was forced to turn its attention inward to deal with the Soviet Union's deep-seated domestic economic problems.[68] During this period, Soviet leaders such as Leonid Brezhnev and Alexei Kosygin embraced the notion of détente.[68]

French NATO withdrawal

Main article: NATO § French withdrawal from NATO command

The unity of NATO was breached early in its history, with a crisis occurring during Charles de Gaulle's

presidency of France from 1958 onwards. De Gaulle protested at the

United States' strong role in the organization and what he perceived as a

special relationship between the United States and the United Kingdom. In a memorandum sent to President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Prime Minister Harold Macmillan

on 17 September 1958, he argued for the creation of a tripartite

directorate that would put France on an equal footing with the United

States and the United Kingdom, and also for the expansion of NATO's

coverage to include geographical areas of interest to France, most

notably French Algeria, where France was waging a counter-insurgency and sought NATO assistance.[176]Considering the response given to be unsatisfactory, de Gaulle began the development of an independent French nuclear deterrent and in 1966 withdrew from NATO's military structures and expelled NATO troops from French soil.[177]

Czechoslovakia invasion

Main articles: Prague Spring and Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia

In 1968, a period of political liberalization in Czechoslovakia called the Prague Spring took place that included "Action Program" of liberalizations, which described increasing freedom of the press, freedom of speech and freedom of movement, along with an economic emphasis on consumer goods, the possibility of a multiparty government, limiting the power of the secret police[178][179] and potentially withdrawing from the Warsaw Pact.[180]In answer to the Prague Spring, the Soviet army, together with most of their Warsaw Pact allies, invaded Czechoslovakia.[181] The invasion was followed by a wave of emigration, including an estimated 70,000 Czechs and Slovaks initially fleeing, with the total eventually reaching 300,000.[182] The invasion sparked intense protests from Yugoslavia, Romania and China, and from Western European communist parties.[183]

Brezhnev Doctrine

Main article: Brezhnev Doctrine

Leonid Brezhnev and Richard Nixon

during Brezhnev's June 1973 visit to Washington; this was a high-water

mark in détente between the United States and the Soviet Union.

When forces that are hostile to socialism try to turn the development of some socialist country towards capitalism, it becomes not only a problem of the country concerned, but a common problem and concern of all socialist countries.The doctrine found its origins in the failures of Marxism–Leninism in states like Poland, Hungary and East Germany, which were facing a declining standard of living contrasting with the prosperity of West Germany and the rest of Western Europe.[184]

Third World escalations

See also: United States occupation of the Dominican Republic (1965–1966), Indonesian killings of 1965–1966, Vietnam War, 1973 Chilean coup d'état, 1973 Uruguayan coup d'état, 1976 Argentine coup d'état, Operation Condor, Six Day War, Task Force 74, War of Attrition, Yom Kippur War, Ogaden War, Angolan Civil War, Indonesian invasion of East Timor, Reeducation camp, Vietnamese boat people and Stability-instability paradox

Alexei Kosygin (left) next to US President Lyndon B. Johnson (right) during the Glassboro Summit Conference

In Indonesia, the hardline anti-communist General Suharto wrested control of the state from his predecessor Sukarno in an attempt to establish a "New Order". From 1965 to 1966, the military led the mass killing of an estimated half-million members and sympathizers of the Indonesian Communist Party and other leftist organizations.[187]

Escalating the scale of American intervention in the ongoing conflict between Ngô Đình Diệm's South Vietnamese government and the communist National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF) insurgents opposing it, Johnson deployed some 575,000 troops in Southeast Asia to defeat the NLF and their North Vietnamese allies in the Vietnam War, but his costly policy weakened the US economy and, by 1975, ultimately culminated in what most of the world saw as a humiliating defeat of the world's most powerful superpower at the hands of one of the world's poorest nations.[14] North Vietnam received Soviet approval for its war effort in 1959; the Soviet Union sent 15,000 military advisors and annual arms shipments worth $450 million to North Vietnam during the war, while China sent 320,000 troops and annual arms shipments worth $180 million.[188]

In Chile, the Socialist Party candidate Salvador Allende won the presidential election of 1970, becoming the first democratically elected Marxist to become president of a country in the Americas.[189] The CIA targeted Allende for removal and operated to undermine his support domestically, which contributed to a period of unrest culminating in General Augusto Pinochet's coup d'état on 11 September 1973. Pinochet consolidated power as a military dictator, Allende's reforms of the economy were rolled back, and leftist opponents were killed or detained in internment camps under the Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional (DINA).

Henry Kissinger, who was US National Security Advisor and Secretary of State under Presidents Nixon and Ford, was a central figure in the Cold War while in office (1969–1977).

American prisoner of war speaking with a North Vietnamese Army officer, 1973

The 1974 Portuguese Carnation Revolution against the authoritarian Estado Novo returned Portugal to a multi-party system and facilitated the independence of the Portuguese colonies Angola and East Timor. In Africa, where Angolan rebels had waged a multi-faction independence war against Portuguese rule since 1961, a two-decade civil war replaced the anti-colonial struggle as fighting erupted between the communist People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), backed by the Cubans and Soviets, and the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA), backed by the United States, the People's Republic of China, and Mobutu's government in Zaire. The United States, the apartheid government of South Africa, and several other African governments also supported a third faction, the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA). Without bothering to consult the Soviets in advance, the Cuban government sent a number of combat troops to fight alongside the MPLA.[195] Foreign mercenaries and a South African armoured column were deployed to support UNITA, but the MPLA, bolstered by Cuban personnel and Soviet assistance, eventually gained the upper hand.[195]

During the Vietnam War, North Vietnam invaded and occupied parts of Cambodia to use as military bases, which contributed to the violence of the Cambodian Civil War between the pro-American government of Lon Nol and Maoist Khmer Rouge insurgents. Documents uncovered from the Soviet archives reveal that the North Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia in 1970 was launched at the request of the Khmer Rouge after negotiations with Nuon Chea.[199] US and South Vietnamese forces responded to these actions with a bombing campaign and ground incursion, the effects of which are disputed by historians.[200] Under the leadership of Pol Pot, the Khmer Rouge would eventually kill 1–3 million Cambodians in the killing fields, out of a 1975 population of roughly 8 million.[201][202][203] Martin Shaw described these atrocities as "the purest genocide of the Cold War era."[204] Vietnam deposed Pol Pot in 1979 and installed Khmer Rouge defector Heng Samrin, only to be bogged down in a guerilla war and suffer a punitive Chinese attack.

Sino-American rapprochement

Main article: 1972 Nixon visit to China

Richard Nixon meets with Mao Zedong in 1972.

In February 1972, Nixon announced a stunning rapprochement with Mao's China[206] by traveling to Beijing and meeting with Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai. At this time, the USSR achieved rough nuclear parity with the United States; meanwhile, the Vietnam War both weakened America's influence in the Third World and cooled relations with Western Europe.[207] Although indirect conflict between Cold War powers continued through the late 1960s and early 1970s, tensions were beginning to ease.[118]

Nixon, Brezhnev, and détente

Main articles: Strategic Arms Limitation Talks, Vladivostok Summit Meeting on Arms Control, Helsinki Accords and Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe

Following his China visit, Nixon met with Soviet leaders, including Brezhnev in Moscow.[208] These Strategic Arms Limitation Talks resulted in two landmark arms control treaties: SALT I, the first comprehensive limitation pact signed by the two superpowers,[209] and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty,

which banned the development of systems designed to intercept incoming

missiles. These aimed to limit the development of costly anti-ballistic

missiles and nuclear missiles.[68]Nixon and Brezhnev proclaimed a new era of "peaceful coexistence" and established the groundbreaking new policy of détente (or cooperation) between the two superpowers. Meanwhile, Brezhnev attempted to revive the Soviet economy, which was declining in part because of heavy military expenditures.[14] Between 1972 and 1974, the two sides also agreed to strengthen their economic ties,[14] including agreements for increased trade. As a result of their meetings, détente would replace the hostility of the Cold War and the two countries would live mutually.[208]

Meanwhile, these developments coincided with the "Ostpolitik" of West German Chancellor Willy Brandt.[183] Other agreements were concluded to stabilize the situation in Europe, culminating in the Helsinki Accords signed at the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe in 1975.[210]

Late 1970s deterioration of relations

In the 1970s, the KGB, led by Yuri Andropov, continued to persecute distinguished Soviet personalities such as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Andrei Sakharov, who were criticising the Soviet leadership in harsh terms.[211] Indirect conflict between the superpowers continued through this period of détente in the Third World, particularly during political crises in the Middle East, Chile, Ethiopia, and Angola.[212]Although President Jimmy Carter tried to place another limit on the arms race with a SALT II agreement in 1979,[213] his efforts were undermined by the other events that year, including the Iranian Revolution and the KGB-backed[214] Nicaraguan Revolution, which both ousted pro-US regimes, and his retaliation against Soviet intervention in Afghanistan in December.[14]

"Second Cold War" (1979–85)

Main article: Cold War (1979–1985)

The term second Cold War refers to the period of intensive

reawakening of Cold War tensions and conflicts in the late 1970s and

early 1980s. Tensions greatly increased between the major powers with

both sides becoming more militaristic.[10] Diggins says, "Reagan went all out to fight the second cold war, by supporting counterinsurgencies in the third world."[215] Cox says, "The intensity of this 'second' Cold War was as great as its duration was short."[216]Soviet war in Afghanistan

Main articles: War in Afghanistan (1978–present) and Soviet war in Afghanistan

President Reagan publicizes his support by meeting with Afghan Mujahideen leaders in the White House, 1983

In September 1979, Khalqist President Nur Muhammad Taraki was assassinated in a coup within the PDPA orchestrated by fellow Khalq member Hafizullah Amin, who assumed the presidency. Distrusted by the Soviets, Amin was assassinated by Soviet special forces in December 1979. A Soviet-organized government, led by Parcham's Babrak Karmal but inclusive of both factions, filled the vacuum. Soviet troops were deployed to stabilize Afghanistan under Karmal in more substantial numbers, although the Soviet government did not expect to do most of the fighting in Afghanistan. As a result, however, the Soviets were now directly involved in what had been a domestic war in Afghanistan.[221]

Carter responded to the Soviet intervention by withdrawing the SALT II treaty from the Senate, imposing embargoes on grain and technology shipments to the USSR, and demanding a significant increase in military spending, and further announced that the United States would boycott the 1980 Moscow Summer Olympics. He described the Soviet incursion as "the most serious threat to the peace since the Second World War".[222]

Reagan and Thatcher

Further information: Reagan Doctrine and Strategic Defense Initiative

Thatcher's Ministry meets with Reagan's Cabinet at the White House, 1981

By early 1985, Reagan's anti-communist position had developed into a stance known as the new Reagan Doctrine—which, in addition to containment, formulated an additional right to subvert existing communist governments.[226] Besides continuing Carter's policy of supporting the Islamic opponents of the Soviet Union and the Soviet-backed PDPA government in Afghanistan, the CIA also sought to weaken the Soviet Union itself by promoting political Islam in the majority-Muslim Central Asian Soviet Union.[227] Additionally, the CIA encouraged anti-communist Pakistan's ISI to train Muslims from around the world to participate in the jihad against the Soviet Union.[227]

Polish Solidarity movement and martial law

Main articles: Solidarity (Polish trade union) and Martial law in Poland

Further information: Soviet reaction to the Polish crisis of 1980–1981

Pope John Paul II provided a moral focus for anti-communism; a visit to his native Poland in 1979 stimulated a religious and nationalist resurgence centered on the Solidarity movement that galvanized opposition and may have led to his attempted assassination two years later.[228]In December 1981, Poland's Wojciech Jaruzelski reacted to the crisis by imposing a period of martial law. Reagan imposed economic sanctions on Poland in response.[229] Mikhail Suslov, the Kremlin's top ideologist, advised Soviet leaders not to intervene if Poland fell under the control of Solidarity, for fear it might lead to heavy economic sanctions, representing a catastrophe for the Soviet economy.[229]

Soviet and US military and economic issues

Further information: Brezhnev stagnation, Strategic Defense Initiative, RSD-10 Pioneer and MGM-31 Pershing

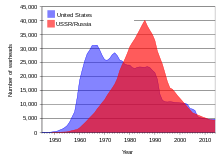

US and USSR/Russian nuclear weapons stockpiles, 1945–2006

Delta 183 launch vehicle lifts off, carrying the Strategic Defense Initiative sensor experiment "Delta Star".

Soviet investment in the defense sector was not driven by military necessity, but in large part by the interests of massive party and state bureaucracies dependent on the sector for their own power and privileges.[232] The Soviet Armed Forces became the largest in the world in terms of the numbers and types of weapons they possessed, in the number of troops in their ranks, and in the sheer size of their military–industrial base.[233] However, the quantitative advantages held by the Soviet military often concealed areas[which?] where the Eastern Bloc dramatically lagged behind the West.[234]

After ten-year-old American Samantha Smith wrote a letter to Yuri Andropov expressing her fear of nuclear war, Andropov invited Smith to the Soviet Union.

Tensions continued intensifying in the early 1980s when Reagan revived the B-1 Lancer program that was canceled by the Carter administration, produced LGM-118 Peacekeepers,[237] installed US cruise missiles in Europe, and announced his experimental Strategic Defense Initiative, dubbed "Star Wars" by the media, a defense program to shoot down missiles in mid-flight.[238]

With the background of a buildup in tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States, and the deployment of Soviet RSD-10 Pioneer ballistic missiles targeting Western Europe, NATO decided, under the impetus of the Carter presidency, to deploy MGM-31 Pershing and cruise missiles in Europe, primarily West Germany.[239] This deployment would have placed missiles just 10 minutes' striking distance from Moscow.[240]

After Reagan's military buildup, the Soviet Union did not respond by further building its military[241] because the enormous military expenses, along with inefficient planned manufacturing and collectivized agriculture, were already a heavy burden for the Soviet economy.[242] At the same time, Saudi Arabia increased oil production,[243] even as other non-OPEC nations were increasing production.[244] These developments contributed to the 1980s oil glut, which affected the Soviet Union, as oil was the main source of Soviet export revenues.[230][242] Issues with command economics,[245] oil price decreases and large military expenditures gradually brought the Soviet economy to stagnation.[242]

On 1 September 1983, the Soviet Union shot down Korean Air Lines Flight 007, a Boeing 747 with 269 people aboard, including sitting Congressman Larry McDonald, when it violated Soviet airspace just past the west coast of Sakhalin Island near Moneron Island—an act which Reagan characterized as a "massacre". This act increased support for military deployment, overseen by Reagan, which stood in place until the later accords between Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev.[246] The Able Archer 83 exercise in November 1983, a realistic simulation of a coordinated NATO nuclear release, has been called the most dangerous moment since the Cuban Missile Crisis, as the Soviet leadership keeping a close watch on it considered a nuclear attack to be imminent.[247]

US domestic public concerns about intervening in foreign conflicts persisted from the end of the Vietnam War.[248] The Reagan administration emphasized the use of quick, low-cost counter-insurgency tactics to intervene in foreign conflicts.[248] In 1983, the Reagan administration intervened in the multisided Lebanese Civil War, invaded Grenada, bombed Libya and backed the Central American Contras, anti-communist paramilitaries seeking to overthrow the Soviet-aligned Sandinista government in Nicaragua.[98] While Reagan's interventions against Grenada and Libya were popular in the United States, his backing of the Contra rebels was mired in controversy.[249]

Meanwhile, the Soviets incurred high costs for their own foreign interventions. Although Brezhnev was convinced in 1979 that the Soviet war in Afghanistan would be brief, Muslim guerrillas, aided by the US, China, Britain, Saudi Arabia and Pakistan,[219] waged a fierce resistance against the invasion.[250] The Kremlin sent nearly 100,000 troops to support its puppet regime in Afghanistan, leading many outside observers to dub the war "the Soviets' Vietnam".[250] However, Moscow's quagmire in Afghanistan was far more disastrous for the Soviets than Vietnam had been for the Americans because the conflict coincided with a period of internal decay and domestic crisis in the Soviet system.

A senior US State Department official predicted such an outcome as early as 1980, positing that the invasion resulted in part from a "domestic crisis within the Soviet system. ... It may be that the thermodynamic law of entropy has ... caught up with the Soviet system, which now seems to expend more energy on simply maintaining its equilibrium than on improving itself. We could be seeing a period of foreign movement at a time of internal decay".[251][252]

Final years (1985–91)

Main article: Cold War (1985–1991)

Further information: Reagan Doctrine

Mikhail Gorbachev and Ronald Reagan sign the INF Treaty at the White House, 1987

Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan in 1988.

The beginning of the 1990s brought a thaw in relations between the superpowers.

Gorbachev reforms

By the time the comparatively youthful Mikhail Gorbachev became General Secretary in 1985,[225] the Soviet economy was stagnant and faced a sharp fall in foreign currency earnings as a result of the downward slide in oil prices in the 1980s.[253] These issues prompted Gorbachev to investigate measures to revive the ailing state.[253]An ineffectual start led to the conclusion that deeper structural changes were necessary and in June 1987 Gorbachev announced an agenda of economic reform called perestroika, or restructuring.[254] Perestroika relaxed the production quota system, allowed private ownership of businesses and paved the way for foreign investment. These measures were intended to redirect the country's resources from costly Cold War military commitments to more productive areas in the civilian sector.[254]

Despite initial skepticism in the West, the new Soviet leader proved to be committed to reversing the Soviet Union's deteriorating economic condition instead of continuing the arms race with the West.[118][255] Partly as a way to fight off internal opposition from party cliques to his reforms, Gorbachev simultaneously introduced glasnost, or openness, which increased freedom of the press and the transparency of state institutions.[256] Glasnost was intended to reduce the corruption at the top of the Communist Party and moderate the abuse of power in the Central Committee.[257] Glasnost also enabled increased contact between Soviet citizens and the western world, particularly with the United States, contributing to the accelerating détente between the two nations.[258]

Thaw in relations

Further information: Reykjavík Summit, Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, START I and Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany

In response to the Kremlin's military and political concessions, Reagan agreed to renew talks on economic issues and the scaling-back of the arms race.[259] The first was held in November 1985 in Geneva, Switzerland.[259]

At one stage the two men, accompanied only by an interpreter, agreed in

principle to reduce each country's nuclear arsenal by 50 percent.[260] A second Reykjavík Summit was held in Iceland.

Talks went well until the focus shifted to Reagan's proposed Strategic

Defense Initiative, which Gorbachev wanted eliminated. Reagan refused.[261] The negotiations failed, but the third summit in 1987 led to a breakthrough with the signing of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty

(INF). The INF treaty eliminated all nuclear-armed, ground-launched

ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges between 500 and

5,500 kilometers (300 to 3,400 miles) and their infrastructure.[262]East–West tensions rapidly subsided through the mid-to-late 1980s, culminating with the final summit in Moscow in 1989, when Gorbachev and George H. W. Bush signed the START I arms control treaty.[263] During the following year it became apparent to the Soviets that oil and gas subsidies, along with the cost of maintaining massive troops levels, represented a substantial economic drain.[264] In addition, the security advantage of a buffer zone was recognised as irrelevant and the Soviets officially declared that they would no longer intervene in the affairs of allied states in Central and Eastern Europe.[265]

In 1989, Soviet forces withdrew from Afghanistan[266] and by 1990 Gorbachev consented to German reunification,[264] the only alternative being a Tiananmen scenario.[267] When the Berlin Wall came down, Gorbachev's "Common European Home" concept began to take shape.[268]

On 3 December 1989, Gorbachev and Reagan's successor, George H. W. Bush, declared the Cold War over at the Malta Summit;[269] a year later, the two former rivals were partners in the Gulf War against Iraq.[270]

East Europe breaks away

Main article: Revolutions of 1989

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

Soviet republics break away

Further information: Economy of the Soviet Union and Baltic Way

In the USSR itself, glasnost weakened the bonds that held the Soviet Union together[265] and by February 1990, with the dissolution of the USSR looming, the Communist Party was forced to surrender its 73-year-old monopoly on state power.[274] At the same time freedom of press and dissent allowed by glasnost

and the festering "nationalities question" increasingly led the Union's

component republics to declare their autonomy from Moscow, with the Baltic states withdrawing from the Union entirely.[275]Soviet dissolution

Further information: January 1991 events in Latvia, 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt, History of the Soviet Union (1982–1991) and Dissolution of the Soviet Union

Commonwealth of Independent States, the official end of the Soviet Union

Aftermath

Main article: Effects of the Cold War

The Cold War continues to influence world affairs. The post–Cold War world is considered to be unipolar, with the United States the sole remaining superpower.[281][282][283] The Cold War defined the political role of the United States after World War II—by 1989 the United States had military alliances with 50 countries, with 526,000 troops stationed abroad,[284] with 326,000 in Europe (two-thirds of which in west Germany)[285] and 130,000 in Asia (mainly Japan and South Korea).[284] The Cold War also marked the zenith of peacetime military-industrial complexes, especially in the United States, and large-scale military funding of science.[286] These complexes, though their origins may be found as early as the 19th century, snowballed considerably during the Cold War.[287]

Cumulative U.S. military expenditures throughout the entire Cold War amounted to an estimated $8 trillion. Further nearly 100,000 Americans lost their lives in the Korean and Vietnam Wars.[288] Although Soviet casualties are difficult to estimate, as a share of their gross national product the financial cost for the Soviet Union was much higher than that incurred by the United States.[289]

Changes in national boundaries after the end of the Cold War

The aftermath of Cold War conflict, however, is not always easily erased, as many of the economic and social tensions that were exploited to fuel Cold War competition in parts of the Third World remain acute. The breakdown of state control in a number of areas formerly ruled by communist governments produced new civil and ethnic conflicts, particularly in the former Yugoslavia. In Central and Eastern Europe, the end of the Cold War has ushered in an era of economic growth and an increase in the number of liberal democracies, while in other parts of the world, such as Afghanistan, independence was accompanied by state failure.[10]

In popular culture

See also: Culture during the Cold War

During the Cold War itself, with the United States and the Soviet

Union invested heavily in propaganda designed to influence the hearts

and minds of people around the world, especially using motion pictures. [292][page needed]The Cold War endures as a popular topic reflected extensively in entertainment media, and continuing to the present with numerous post-1991 Cold War-themed feature films, novels, television, and other media. In 2013, a KGB-sleeper-agents-living-next-door action drama series, The Americans, set in the early 1980s, was ranked #6 on the Metacritic annual Best New TV Shows list and is in its second season.[293] At the same time, movies like Crimson Tide (1995) are shown in their entirety to educate college students about the Cold War.[294]

Historiography

Main article: Historiography of the Cold War

As soon as the term "Cold War" was popularized to refer to post-war

tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, interpreting

the course and origins of the conflict has been a source of heated

controversy among historians, political scientists, and journalists.[295]

In particular, historians have sharply disagreed as to who was

responsible for the breakdown of Soviet–US relations after the Second

World War; and whether the conflict between the two superpowers was

inevitable, or could have been avoided.[296]

Historians have also disagreed on what exactly the Cold War was, what

the sources of the conflict were, and how to disentangle patterns of

action and reaction between the two sides.[10]Although explanations of the origins of the conflict in academic discussions are complex and diverse, several general schools of thought on the subject can be identified. Historians commonly speak of three differing approaches to the study of the Cold War: "orthodox" accounts, "revisionism", and "post-revisionism".[286]

"Orthodox" accounts place responsibility for the Cold War on the Soviet Union and its expansion further into Europe.[286] "Revisionist" writers place more responsibility for the breakdown of post-war peace on the United States, citing a range of US efforts to isolate and confront the Soviet Union well before the end of World War II.[286] "Post-revisionists" see the events of the Cold War as more nuanced, and attempt to be more balanced in determining what occurred during the Cold War.[286] Much of the historiography on the Cold War weaves together two or even all three of these broad categories.[30]

See also

- Canada in the Cold War

- Cold War (TV series)

- Culture during the Cold War

- Danube River Conference of 1948

- Index of Soviet Union-related articles

- List of Soviet Union–United States summits

- McCarthyism

- Mutually assured destruction

- Post–World War II economic expansion

- Soviet Empire

- Soviet espionage in the United States

- Timeline of events in the Cold War

- World War III

- Cold War II

- Category:Cold War by period

Footnotes

- Brinkley, pp. 798–799

References and further reading

Main article: List of primary and secondary sources on the Cold War

- Applebaum, Anne (2012). Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe, 1944–1956. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-51569-3.

- Bronson, Rachel. Thicker than Oil: Oil:America's Uneasy Partnership with Saudi Arabia. Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-19-516743-6

- Davis, Simon, and Joseph Smith. The A to Z of the Cold War (Scarecrow, 2005), encyclopedia focused on military aspects

- Dominguez, Jorge I. (1989). To Make a World Safe for Revolution: Cuba's Foreign Policy. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-89325-2.

- Fedorov, Alexander (2011). Russian Image on the Western Screen: Trends, Stereotypes, Myths, Illusions. Lambert Academic Publishing,. ISBN 978-3-8433-9330-0.

- Friedman, Norman (2007). The Fifty-Year War: Conflict and Strategy in the Cold War. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-287-3.

- Gaddis, John Lewis (1990). Russia, the Soviet Union and the United States. An Interpretative History. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-557258-3.

- Gaddis, John Lewis (1997). We Now Know: Rethinking Cold War History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-878070-2.

- Gaddis, John Lewis (2005). The Cold War: A New History. Penguin Press. ISBN 1-59420-062-9.

- Garthoff, Raymond (1994). Détente and Confrontation: American-Soviet Relations from Nixon to Reagan. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 0-8157-3041-1.

- Halliday, Fred. The Making of the Second Cold War (1983, Verso, London).

- Haslam, Jonathan. Russia's Cold War: From the October Revolution to the Fall of the Wall (Yale University Press; 2011) 512 pages

- Heller, Henry (2006). The Cold War and the New Imperialism: A Global History, 1945–2005. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 1-58367-139-0

- Hoffman, David E. The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and Its Dangerous Legacy (2010)

- House, Jonathan. A Military History of the Cold War, 1944–1962 (2012)

- Hussain, Rizwan (2005). Pakistan And The Emergence Of Islamic Militancy In Afghanistan. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0-7546-4434-0.

- Judge, Edward H. The Cold War: A Global History With Documents (2012)

- Kalinovsky, Artemy M. (2011). A Long Goodbye: The Soviet Withdrawal from Afghanistan. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05866-8.

- Kinsella, Warren (1992). Unholy Alliances. Lester Publishing. ISBN 1895555248.

- LaFeber, Walter (1993). America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945–1992. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-035853-2.

- LaFeber, Walter (2002). America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945–2002. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-284903-7.

- Leffler, Melvyn (1992). A Preponderance of Power: National Security, the Truman Administration, and the Cold War. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2218-8.

- Leffler, Melvyn P. and Odd Arne Westad, eds. The Cambridge History of the Cold War (3 vol, 2010) 2000pp; new essays by leading scholars

- Lewkowicz, Nicolas (2010). The German Question and the International Order, 1943–48. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-24812-0.

- Lundestad, Geir (2005). East, West, North, South: Major Developments in International Politics since 1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 1-4129-0748-9.

- Lüthi, Lorenz M (2008). The Sino-Soviet Split: Cold War in the Communist World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-13590-8.