Augusta

Ada King-Noel, Countess of Lovelace was an English mathematician and

writer, chiefly known for her work on Charles Babbage's proposed

mechanical general-purpose computer, the Analytical Engine. Wikipedia

Born: December 10, 1815, London, United Kingdom

Died: November 27, 1852, Marylebone, United Kingdom

Full name: Augusta Ada King

begin quote from:

Ada Lovelace - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ada_Lovelace

Augusta Ada King-Noel, Countess of Lovelace was an English mathematician and writer, ... Ada Lovelace was the only legitimate child of the poet Lord Byron, and his wife Anne Isabella Milbanke ("Annabella"), Lady Wentworth. All of Byron's ...

Ada Byron, Lady Lovelace - Agnes Scott College

https://www.agnesscott.edu/lriddle/women/love.htm

Jun 14, 2017 - Ada Byron, Lady Lovelace, was one of the most picturesque characters in computer history. Augusta Ada Byron was born December 10, 1815 ...

Ada Lovelace - Computer Programmer, Mathematician - Biography.com

https://www.biography.com/people/ada-lovelace-20825323

| Ada, Countess of Lovelace | |

|---|---|

Ada, Countess of Lovelace, 1840

|

|

| Born | The Hon. Augusta Ada Byron 10 December 1815 London, England |

| Died | 27 November 1852 (aged 36) Marylebone, London, England |

| Resting place | Church of St. Mary Magdalene, Hucknall, Nottingham, England |

| Known for | Mathematics Computing |

| Title | Countess of Lovelace |

| Spouse(s) | William King-Noel, 1st Earl of Lovelace |

| Children | |

| Parent(s) | |

Ada Lovelace was the only legitimate child of the poet Lord Byron, and his wife Anne Isabella Milbanke ("Annabella"), Lady Wentworth.[4] All of Byron's other children were born out of wedlock to other women.[5] Byron separated from his wife a month after Ada was born and left England forever four months later. He died of disease in the Greek War of Independence when Ada was eight years old. Her mother remained bitter and promoted Ada's interest in mathematics and logic in an effort to prevent her from developing her father's perceived insanity. Despite this, Ada remained interested in Byron and was, upon her eventual death, buried next to him at her request. She was often ill in her childhood. Ada married William King in 1835. King was made Earl of Lovelace in 1838, and Ada in turn became Countess of Lovelace.

Her educational and social exploits brought her into contact with scientists such as Andrew Crosse, Sir David Brewster, Charles Wheatstone, Michael Faraday and the author Charles Dickens, which she used to further her education. Ada described her approach as "poetical science"[6] and herself as an "Analyst (& Metaphysician)".[7]

When she was a teenager, her mathematical talents led her to a long working relationship and friendship with fellow British mathematician Charles Babbage, also known as "the father of computers", and in particular, Babbage's work on the Analytical Engine. Lovelace first met him in June 1833, through their mutual friend, and her private tutor, Mary Somerville.

Between 1842 and 1843, Ada translated an article by Italian military engineer Luigi Menabrea on the engine, which she supplemented with an elaborate set of notes, simply called Notes. These notes contain what many consider to be the first computer program—that is, an algorithm designed to be carried out by a machine. Lovelace's notes are important in the early history of computers. She also developed a vision of the capability of computers to go beyond mere calculating or number-crunching, while many others, including Babbage himself, focused only on those capabilities.[8] Her mindset of "poetical science" led her to ask questions about the Analytical Engine (as shown in her notes) examining how individuals and society relate to technology as a collaborative tool.[5]

She died of uterine cancer in 1852 at the age of 36.

Contents

Biography

Early life

Byron expected his baby to be a "glorious boy" and was disappointed when his wife gave birth to a girl.[9] Augusta was named after Byron's half-sister, Augusta Leigh, and was called "Ada" by Byron himself.[10]

Ada, aged four

This set of events made Ada famous in Victorian society. Byron did not have a relationship with his daughter, and never saw her again. He died in 1824 when she was eight years old. Her mother was the only significant parental figure in her life.[15] Ada was not shown the family portrait of her father (covered in green shroud) until her twentieth birthday.[16] Her mother became Baroness Wentworth in her own right in 1856.

Annabella did not have a close relationship with the young Ada and often left her in the care of her own mother Judith, Hon. Lady Milbanke who doted on her grandchild. However, because of societal attitudes of the time—which favoured the husband in any separation, with the welfare of any child acting as mitigation—Annabella had to present herself as a loving mother to the rest of society. This included writing anxious letters to Lady Milbanke about Ada's welfare, with a cover note saying to retain the letters in case she had to use them to show maternal concern.[17] In one letter to Lady Milbanke, she referred to Ada as "it": "I talk to it for your satisfaction, not my own, and shall be very glad when you have it under your own."[18] In her teenage years, several of her mother's close friends watched Ada for any sign of moral deviation. Ada dubbed these observers the "Furies" and later complained they exaggerated and invented stories about her.[19]

Ada, aged seventeen, 1832

In early 1833 Ada had an affair with a tutor and, after being caught, tried to elope with him. The tutor's relatives recognised her and contacted her mother. Annabella and her friends covered the incident up to prevent a public scandal.[20] Ada never met her younger half-sister, Allegra, the daughter of Lord Byron and Claire Clairmont. Allegra died in 1822 at the age of five. Ada did have some contact with Elizabeth Medora Leigh, the daughter of Byron's half-sister Augusta Leigh, who purposely avoided Ada as much as possible when introduced at Court.[21]

Adult years

Lovelace became close friends with her tutor Mary Somerville, who introduced her to Charles Babbage in 1833. She had a strong respect and affection for Somerville,[22] and they corresponded for many years. Other acquaintances included the scientists Andrew Crosse, Sir David Brewster, Charles Wheatstone, Michael Faraday and the author Charles Dickens. She was presented at Court at the age of seventeen "and became a popular belle of the season" in part because of her "brilliant mind."[23] By 1834 Ada was a regular at Court and started attending various events. She danced often and was able to charm many people, and was described by most people as being dainty, although John Hobhouse, Byron's friend, described her as "a large, coarse-skinned young woman but with something of my friend's features, particularly the mouth".[24] This description followed their meeting on 24 February 1834 in which Ada made it clear to Hobhouse that she did not like him, probably because of the influence of her mother, which led her to dislike all of her father's friends. This first impression was not to last, and they later became friends.[25]On 8 July 1835, she married William, 8th Baron King, becoming Lady King.[26] They had three homes: Ockham Park, Surrey, a Scottish estate on Loch Torridon in Ross-shire, and a house in London. They spent their honeymoon at Worthy Manor in Ashley Combe near Porlock Weir, Somerset. The Manor had been built as a hunting lodge in 1799 and was improved by King in preparation for their honeymoon. It later became their summer retreat and was further improved during this time. From 1845 the family's main house was East Horsley Towers, rebuilt in the Victorian Gothic fashion by the architect of the Houses of Parliament, Charles Barry.[27][28]

They had three children: Byron (born 12 May 1836); Anne Isabella (called Annabella; born 22 September 1837); and Ralph Gordon (born 2 July 1839). Immediately after the birth of Annabella, Lady King experienced "a tedious and suffering illness, which took months to cure."[25] Ada was a descendant of the extinct Barons Lovelace and in 1838, her husband was made Earl of Lovelace and Viscount Ockham,[29] meaning Ada became the Countess of Lovelace. In 1843–44, Ada's mother assigned William Benjamin Carpenter to teach Ada's children and to act as a "moral" instructor for Ada.[30] He quickly fell for her and encouraged her to express any frustrated affections, claiming that his marriage meant he would never act in an "unbecoming" manner. When it became clear that Carpenter was trying to start an affair, Ada cut it off.[31]

In 1841 Lovelace and Medora Leigh (the daughter of Lord Byron's half-sister Augusta Leigh) were told by Ada's mother that her father was also Medora's father.[32] On 27 February 1841, Ada wrote to her mother: "I am not in the least astonished. In fact, you merely confirm what I have for years and years felt scarcely a doubt about, but should have considered it most improper in me to hint to you that I in any way suspected."[33] She did not blame the incestuous relationship on Byron, but instead blamed Augusta Leigh: "I fear she is more inherently wicked than he ever was."[34] In the 1840s Ada flirted with scandals: first, from a relaxed relationship with men who were not her husband, which led to rumours of affairs[35]—and secondly, her love of gambling. She apparently lost more than £3,000 on the horses during the later 1840s.[36] The gambling led to her forming a syndicate with male friends, and an ambitious attempt in 1851 to create a mathematical model for successful large bets. This went disastrously wrong, leaving her thousands of pounds in debt to the syndicate, forcing her to admit it all to her husband.[37] She had a shadowy relationship with Andrew Crosse's son John from 1844 onwards. John Crosse destroyed most of their correspondence after her death as part of a legal agreement. She bequeathed him the only heirlooms her father had personally left to her.[38] During her final illness, she would panic at the idea of the younger Crosse being kept from visiting her.[39]

Education

Throughout her illnesses, she continued her education.[40] Her mother's obsession with rooting out any of the insanity of which she accused Byron was one of the reasons that Ada was taught mathematics from an early age. She was privately schooled in mathematics and science by William Frend, William King,[a] and Mary Somerville, the noted researcher and scientific author of the 19th century. One of her later tutors was the mathematician and logician Augustus De Morgan. From 1832, when she was seventeen, her mathematical abilities began to emerge,[23] and her interest in mathematics dominated the majority of her adult life. In a letter to Lady Byron, De Morgan suggested that her daughter's skill in mathematics could lead her to become "an original mathematical investigator, perhaps of first-rate eminence".[41]Lovelace often questioned basic assumptions by integrating poetry and science. While studying differential calculus, she wrote to De Morgan:

I may remark that the curious transformations many formulae can undergo, the unsuspected and to a beginner apparently impossible identity of forms exceedingly dissimilar at first sight, is I think one of the chief difficulties in the early part of mathematical studies. I am often reminded of certain sprites and fairies one reads of, who are at one's elbows in one shape now, and the next minute in a form most dissimilar[42]Lovelace believed that intuition and imagination were critical to effectively applying mathematical and scientific concepts. She valued metaphysics as much as mathematics, viewing both as tools for exploring "the unseen worlds around us".[43]

Death

Painting of Ada Lovelace at a piano in 1852 by Henry Phillips. While she

was in great pain at the time, she sat for the painting as Phillips'

father, Thomas Phillips, had painted Ada's father, Lord Byron.

Work

Throughout her life, Lovelace was strongly interested in scientific developments and fads of the day, including phrenology[48] and mesmerism.[49] After her work with Babbage, Lovelace continued to work on other projects. In 1844 she commented to a friend Woronzow Greig about her desire to create a mathematical model for how the brain gives rise to thoughts and nerves to feelings ("a calculus of the nervous system").[50] She never achieved this, however. In part, her interest in the brain came from a long-running pre-occupation, inherited from her mother, about her 'potential' madness. As part of her research into this project, she visited the electrical engineer Andrew Crosse in 1844 to learn how to carry out electrical experiments.[51] In the same year, she wrote a review of a paper by Baron Karl von Reichenbach, Researches on Magnetism, but this was not published and does not appear to have progressed past the first draft.[52] In 1851, the year before her cancer struck, she wrote to her mother mentioning "certain productions" she was working on regarding the relation of maths and music.[53]

Portrait of Ada by British painter Margaret Sarah Carpenter (1836)

Forget this world and all its troubles and if possible its multitudinous Charlatans—every thing in short but the Enchantress of Number.[55]

One of only two photos of Ada. This daguerreotype was by Antoine Claudet and was made about the time she was creating her Notes[56]

The notes are around three times longer than the article itself and include (in Section G[61]), in complete detail, a method for calculating a sequence of Bernoulli numbers with the Engine, which could have run correctly had Babbage's Analytical Engine been built.[62] (Only his Difference Engine has been built, completed in London in 2002.[63]) Based on this work Lovelace is now widely considered the first computer programmer[1] and her method is recognised as the world's first computer program.[64]

Section G also contains Lovelace's dismissal of artificial intelligence. She wrote that "The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform. It can follow analysis; but it has no power of anticipating any analytical relations or truths." This objection has been the subject of much debate and rebuttal, for example by Alan Turing in his paper "Computing Machinery and Intelligence".[65]

Lovelace and Babbage had a minor falling out when the papers were published when he tried to leave his own statement (a criticism of the government's treatment of his Engine) as an unsigned preface—which would imply that she had written that also. When Taylor's Scientific Memoirs ruled that the statement should be signed, Babbage wrote to Lovelace asking her to withdraw the paper. This was the first that she knew he was leaving it unsigned, and she wrote back refusing to withdraw the paper. The historian Benjamin Woolley theorised that: "His actions suggested he had so enthusiastically sought Ada's involvement, and so happily indulged her ... because of her 'celebrated name'."[66] Their friendship recovered, and they continued to correspond. On 12 August 1851, when she was dying of cancer, Lovelace wrote to him asking him to be her executor, though this letter did not give him the necessary legal authority. Part of the terrace at Worthy Manor was known as Philosopher's Walk, as it was there that Lovelace and Babbage were reputed to have walked while discussing mathematical principles.[60]

First computer program

Lovelace's diagram from Note G, the first published computer algorithm

Ada Lovelace's notes were labelled alphabetically from A to G. In note G, she describes an algorithm for the Analytical Engine to compute Bernoulli numbers. It is considered the first published algorithm ever specifically tailored for implementation on a computer, and Ada Lovelace has often been cited as the first computer programmer for this reason.[67][68] The engine was never completed so her program was never tested.[69]

In 1953, more than a century after her death, Ada Lovelace's notes on Babbage's Analytical Engine were republished. The engine has now been recognised as an early model for a computer and her notes as a description of a computer and software.[62]

Beyond numbers

In her notes, Lovelace emphasised the difference between the Analytical Engine and previous calculating machines, particularly its ability to be programmed to solve problems of any complexity.[70] She realised the potential of the device extended far beyond mere number crunching. In her notes, she wrote:[The Analytical Engine] might act upon other things besides number, were objects found whose mutual fundamental relations could be expressed by those of the abstract science of operations, and which should be also susceptible of adaptations to the action of the operating notation and mechanism of the engine...Supposing, for instance, that the fundamental relations of pitched sounds in the science of harmony and of musical composition were susceptible of such expression and adaptations, the engine might compose elaborate and scientific pieces of music of any degree of complexity or extent.[71][72]This analysis was an important development from previous ideas about the capabilities of computing devices and anticipated the implications of modern computing one hundred years before they were realised. Walter Isaacson ascribes Lovelace's insight regarding the application of computing to any process based on logical symbols to an observation about textiles: "When she saw some mechanical looms that used punchcards to direct the weaving of beautiful patterns, it reminded her of how Babbage's engine used punched cards to make calculations."[73] This insight is seen as significant by writers such as Betty Toole and Benjamin Woolley, as well as the programmer John Graham-Cumming, whose project Plan 28 has the aim of constructing the first complete Analytical Engine.[74][75][76]

According to the historian of computing and Babbage specialist Doron Swade:

Ada saw something that Babbage in some sense failed to see. In Babbage's world his engines were bound by number...What Lovelace saw—what Ada Byron saw—was that number could represent entities other than quantity. So once you had a machine for manipulating numbers, if those numbers represented other things, letters, musical notes, then the machine could manipulate symbols of which number was one instance, according to rules. It is this fundamental transition from a machine which is a number cruncher to a machine for manipulating symbols according to rules that is the fundamental transition from calculation to computation—to general-purpose computation—and looking back from the present high ground of modern computing, if we are looking and sifting history for that transition, then that transition was made explicitly by Ada in that 1843 paper.[1]

Controversy over extent of contributions

Though Lovelace is referred to as the first computer programmer, some biographers and historians of computing claim otherwise.Allan G. Bromley, in the 1990 article Difference and Analytical Engines:

All but one of the programs cited in her notes had been prepared by Babbage from three to seven years earlier. The exception was prepared by Babbage for her, although she did detect a 'bug' in it. Not only is there no evidence that Ada ever prepared a program for the Analytical Engine, but her correspondence with Babbage shows that she did not have the knowledge to do so.[77]Bruce Collier, who later wrote a biography of Babbage, wrote in his 1970 Harvard University PhD thesis that Lovelace "made a considerable contribution to publicizing the Analytical Engine, but there is no evidence that she advanced the design or theory of it in any way".[78]

Eugene Eric Kim and Betty Alexandra Toole consider it "incorrect" to regard Lovelace as the first computer programmer, as Babbage wrote the initial programs for his Analytical Engine, although the majority were never published.[79] Bromley notes several dozen sample programs prepared by Babbage between 1837 and 1840, all substantially predating Lovelace's notes.[80] Dorothy K. Stein regards Lovelace's notes as "more a reflection of the mathematical uncertainty of the author, the political purposes of the inventor, and, above all, of the social and cultural context in which it was written, than a blueprint for a scientific development".[81]

In his book, Idea Makers, Stephen Wolfram defends Lovelace's contributions. While acknowledging that Babbage wrote several unpublished algorithms for the Analytical Engine prior to Lovelace's notes, Wolfram argues that "there's nothing as sophisticated—or as clean—as Ada's computation of the Bernoulli numbers. Babbage certainly helped and commented on Ada's work, but she was definitely the driver of it." Wolfram then suggests that Lovelace's main achievement was to distill from Babbage's correspondence "a clear exposition of the abstract operation of the machine—something which Babbage never did."[82]

Doron Swade, a specialist on history of computing known for his work on Babbage, analyzed four claims about Lovelace during a lecture on Babbage's analytical engine:

- She was a mathematical genius

- She made an influential contribution to the analytical engine

- She was the first computer programmer

- She was a prophet of the computer age

In popular culture

An illustration inspired by the A. E. Chalon portrait created for the Ada Initiative, which supported open technology and women

In Tom Stoppard's 1993 play Arcadia, the precocious teenage genius Thomasina Coverly (a character "apparently based" on Ada Lovelace—the play also involves Lord Byron) comes to understand chaos theory, and theorises the second law of thermodynamics, before either is officially recognised.[88][89] The 2015 play Ada and the Memory Engine by Lauren Gunderson portrays Lovelace and Charles Babbage in unrequited love, and it imagines a post-death meeting between Lovelace and her father.[90][91]

Lovelace and Babbage are the main characters in Sydney Padua's webcomic and graphic novel The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage. The comic features extensive footnotes on the history of Ada Lovelace, and many lines of dialogue are drawn from actual correspondence.[92]

Lovelace and Mary Shelley as teenagers are the central characters in Jordan Stratford's steampunk series, The Wollstonecraft Detective Agency.[93]

In 2017, a Google Doodle honoured her on International Women's Day.[94] Lovelace and Babbage appear as characters in the ITV series Victoria.[95] In September 2017, the Family Coppola launched a gin named after Ada Lovelace.[96]

Commemoration

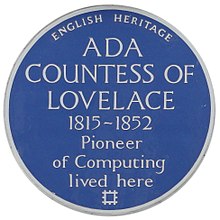

Blue plaque to Lovelace in St. James's Square, London

Since 1998 the British Computer Society (BCS) has awarded the Lovelace Medal,[97] and in 2008 initiated an annual competition for women students.[98] BCSWomen sponsors the Lovelace Colloquium, an annual conference for women undergraduates.[98] Ada College is a further-education college in Tottenham Hale, London focused on digital skills.[99]

Ada Lovelace Day is an annual event celebrated in mid-October[100] whose goal is to "... raise the profile of women in science, technology, engineering, and maths," (see Women in STEM fields) and to "create new role models for girls and women" in these fields. The Ada Initiative was a non-profit organisation dedicated to increasing the involvement of women in the free culture and open source movements.[101]

The Engineering in Computer Science and Telecommunications College building in Zaragoza University is called the Ada Byron Building.[102] The computer centre in the village of Porlock, near where Lovelace lived, is named after her. Ada Lovelace House is a council-owned building in Kirkby-in-Ashfield, Nottinghamshire, near where Lovelace spent her infancy; the building was once an internet centre[103]

She is also the inspiration and influence for the Ada Developers Academy in Seattle, Washington. The academy is a non-profit that seeks to increase diversity in tech by training women, trans and non-binary people to be software engineers.[104]

One of the tunnel boring machines excavating London's Crossrail project is named Ada.[105]

Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology is an "open-access, multi-modal, [open-]peer-reviewed feminist journal concerned with the intersections of gender, new media, and technology" that began in 2012 and is run by the Fembot Collective.[106]

Titles and styles by which she was known

- 10 December 1815 – 8 July 1835: The Honourable Ada Byron

- 8 July 1835 – 30 June 1838: The Right Honourable The Lady King

- 30 June 1838 – 27 November 1852: The Right Honourable The Countess of Lovelace

Ancestry

| [show]Ancestors of Ada Lovelace |

|---|

Bicentenary

The bicentenary of Ada Lovelace's birth was celebrated with a number of events, including:[107]- The Ada Lovelace Bicentenary Lectures on Computability, Israel Institute for Advanced Studies, 20 December 2015 – 31 January 2016.[108][109]

- Ada Lovelace Symposium, University of Oxford, 13–14 October 2015.[110]

Publications

- Menabrea, Luigi Federico; Lovelace, Ada (1843). "Sketch of the Analytical Engine invented by Charles Babbage... with notes by the translator. Translated by Ada Lovelace". In Richard Taylor. Scientific Memoirs. 3. London: Richard and John E. Taylor. pp. 666–731.

See also

- Great Lives (BBC Radio 4) aired on 17 September 2013 was dedicated to the story of Ada Lovelace.[113]

- Code: Debugging the Gender Gap

- List of pioneers in computer science

- Women in computing

Notes

- Some writers give it as "Enchantress of Numbers".

References

Sources

- Baum, Joan (1986), The Calculating Passion of Ada Byron, Archon, ISBN 0-208-02119-1.

- Elwin, Malcolm (1975), Lord Byron's Family, John Murray.

- Essinger, James (2014), Ada's algorithm: How Lord Byron's daughter Ada Lovelace launched the digital age, Melville House Publishing, ISBN 978-1-61219-408-0.

- Fuegi, J; Francis, J (October–December 2003), "Lovelace & Babbage and the creation of the 1843 'notes'", Annals of the History of Computing, IEEE, 25 (4): 16–26, doi:10.1109/MAHC.2003.1253887.

- Hammerman, Robin; Russell, Andrew L. (2015), Ada's Legacy: Cultures of Computing from the Victorian to the Digital Age, Association for Computing Machinery and Morgan & Claypool, ISBN 9781970001518, doi:10.1145/2809523.

- Isaacson, Walter (2014), The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution, Simon & Schuster.

- Kim, Eugene; Toole, Betty Alexandra (1999). "Ada and the First Computer". Scientific American. 280 (5): 76–81. Bibcode:1999SciAm.280e..76E. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0599-76..

- Lewis, Judith S. (July–August 1995). "Princess of Parallelograms and her daughter: Math and gender in the nineteenth century English aristocracy". Women's Studies International Forum. ScienceDirect. 18 (4): 387–394. doi:10.1016/0277-5395(95)80030-S.

- Marchand, Leslie (1971), Byron A Portrait, John Murray.

- Menabrea, Luigi Federico (1843), "Sketch of the Analytical Engine Invented by Charles Babbage", Scientific Memoirs, 3, archived from the original on 15 September 2008, retrieved 29 August 2008 With notes upon the memoir by the translator.

- Moore, Doris Langley (1977), Ada, Countess of Lovelace, John Murray, ISBN 0 7195 3384 8.

- Moore, Doris Langley (1961), The Late Lord Byron, Philadelphia: Lippincott, ISBN 0-06-013013-X, OCLC 358063.

- Stein, Dorothy (1985), Ada: A Life and a Legacy, MIT Press Series in the History of Computing, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, ISBN 0-262-19242-X.

- Toole, Betty Alexandra (1992), Ada, the Enchantress of Numbers: A Selection from the Letters of Ada Lovelace, and her Description of the First Computer, Strawberry Press, ISBN 0912647094.

- Toole, Betty Alexandra (1998), Ada, the Enchantress of Numbers: Prophet of the Computer Age, Strawberry Press, ISBN 0912647183.

- Turney, Catherine (1972), Byron's Daughter: A Biography of Elizabeth Medora Leigh, Scribner, ISBN 0684127539

- Woolley, Benjamin (February 1999), The Bride of Science: Romance, Reason, and Byron's Daughter, AU: Pan Macmillan, ISBN 0-333-72436-4, retrieved 7 April 2013.

- Woolley, Benjamin (February 2002) [1999], The Bride of Science: Romance, Reason, and Byron's Daughter, McGraw-Hill Ryerson, ISBN 978-0-07138860-3, retrieved 7 April 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ada Lovelace. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ada Lovelace |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Ada Lovelace |

- Works by Ada Lovelace at Open Library

- Ada Lovelace at Goodreads

- "Untangling the Tale of Ada Lovelace". StephenWolfram.com. 10 December 2015.

- "Ada Lovelace: Founder of Scientific Computing". Women in Science. SDSC.

- "Ada Byron, Lady Lovelace". Biographies of Women Mathematicians. Agnes Scott College.

- "Papers of the Noel, Byron and Lovelace families". UK: Archives hub.

- "Ada Lovelace & The Analytical Engine". Babbage. Computer History.

- "Ada & the Analytical Engine". Educause.

- "Ada Lovelace, Countess of Controversy". Tech TV vault. G4 TV.

- "Ada Lovelace" (streaming). In Our Time (audio). UK: The BBC (Radio 4). 6 March 2008.

- "Ada Lovelace's Notes and The Ladies Diary". Yale.

- "The fascinating story Ada Lovelace". Sabine Allaeys (Youtube).

- "Ada Lovelace, the World's First Computer Programmer, on Science and Religion". Maria Popova (Brain).

- "How Ada Lovelace, Lord Byron's Daughter, Became the World's First Computer Programmer". Maria Popova (Brain).

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Ada Lovelace", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

Categories:

- 1815 births

- 1852 deaths

- 19th-century English mathematicians

- 19th-century women scientists

- 19th-century British women writers

- 19th-century British writers

- Ada (programming language)

- British computer scientists

- British countesses

- Burials in Nottinghamshire

- Byron family

- Deaths from cancer in England

- Computer designers

- Daughters of barons

- Deaths from uterine cancer

- English computer programmers

- English computer scientists

- English people of Scottish descent

- English scientists

- English women poets

- Lord Byron

- Women computer scientists

- Women in engineering

- Women in technology

- Women mathematicians

- Women of the Victorian era

Horsley Towers is a large house standing in a park of 300 acres, the seat of the Earl of Lovelace. The old house was rebuilt about 1745. The present house was built by Sir Charles Barry for Mr. Currie on a new site, between 1820 and 1829, in Elizabethan style. Mr. Currie, who owned the combined manors, 1784–1829, rebuilt most of the houses in the village and restored the church.

Then, on Sept. 9, Babbage wrote to Ada, expressing his admiration for her and (famously) describing her as 'Enchantress of Number' and 'my dear and much admired Interpreter'. (Yes, despite what's often quoted, he wrote 'Number' not 'Numbers'.)

Participate in an international science photo competition!

Participate in an international science photo competition!

No comments:

Post a Comment