This very interesting man coined the word Shamanism based upon Russian Shamans in Siberia. However, all tribes around the world had shamans before they had farms. So, farms created state religions and kings. And shamanism changed as people went from hunter gatherers or herders to farmers. When people were farmers they needed shamans less or maybe kings killed shamans more because they might interfere with Kings psychologically or physically dominating their people. So, as shamans were murdered by kings along with Tribal leaders religions changed and people who didn't worship the Kings then were killed or tortured or imprisoned. This is the history of every major religion in regard to Kings and Emperors pretty much.

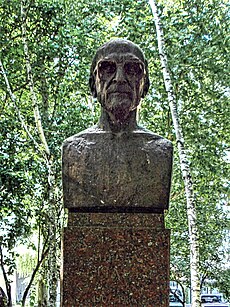

Mircea Eliade

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Eliade" redirects here. For other persons of the same name, see

Eliade (surname).

| Mircea Eliade |

|

| Born |

March 9, 1907

Bucharest, Romania |

| Died |

April 22, 1986 (aged 79)

Chicago, Illinois, United States |

| Occupation |

Historian, philosopher, short story writer, journalist, essayist, novelist |

| Nationality |

Romanian |

| Period |

1921–1986 |

| Genre |

fantasy, autobiography, travel literature |

| Subject |

history of religion, philosophy of religion, cultural history, political history |

| Literary movement |

Modernism

Criterion

Trăirism |

Mircea Eliade (

Romanian: [ˈmirt͡ʃe̯a eliˈade]; March 9 [

O.S. February 24] 1907 – April 22, 1986) was a Romanian historian of religion, fiction writer, philosopher, and professor at the

University of Chicago. He was a leading interpreter of religious experience, who established

paradigms in religious studies that persist to this day. His theory that

hierophanies form the basis of religion, splitting the human experience of reality into

sacred and profane space and time, has proved influential.

[1] One of his most influential contributions to religious studies was his theory of

Eternal Return,

which holds that myths and rituals do not simply commemorate

hierophanies, but, at least to the minds of the religious, actually

participate in them.

[1]

His literary works belong to the

fantastic and

autobiographical genres. The best known are the novels

Maitreyi ("La Nuit

Bengali" or "Bengal Nights"),

Noaptea de Sânziene ("The Forbidden Forest"),

Isabel și apele diavolului ("Isabel and the Devil's Waters") and

Romanul Adolescentului Miop ("Novel of the Nearsighted Adolescent"), the

novellas Domnișoara Christina ("Miss Christina") and

Tinerețe fără tinerețe ("Youth Without Youth"), and the short stories

Secretul doctorului Honigberger ("The Secret of Dr. Honigberger") and

La Țigănci ("With the Gypsy Girls").

Early in his life, Eliade was a journalist and essayist, a disciple of Romanian

far-right philosopher and journalist

Nae Ionescu, and a member of the literary society

Criterion. In the 1940s, he served as cultural attaché to the United Kingdom and Portugal.

Noted for his vast erudition, Eliade had fluent command of five languages (

Romanian, French, German, Italian, and English) and a reading knowledge of three others (

Hebrew,

Persian, and

Sanskrit). He was elected a posthumous member of the

Romanian Academy.

Biography

Childhood

Born in

Bucharest, he was the son of

Romanian Land Forces officer Gheorghe Eliade (whose original surname was Ieremia)

[2][3] and Jeana

née Vasilescu.

[4] An

Orthodox believer, Gheorghe Eliade registered his son's birth four days before the actual date, to coincide with the

liturgical calendar feast of the

Forty Martyrs of Sebaste.

[3] Mircea Eliade had a sister, Corina, the mother of

semiologist Sorin Alexandrescu.

[5][6] His family moved between

Tecuci and Bucharest, ultimately settling in the capital in 1914,

[2] and purchasing a house on Melodiei Street, near

Piața Rosetti, where Mircea Eliade resided until late in his teens.

[6]

Eliade kept a particularly fond memory of his childhood and, later in

life, wrote about the impact various unusual episodes and encounters

had on his mind. In one instance during the

World War I Romanian Campaign, when Eliade was about ten years of age, he witnessed the bombing of Bucharest by

German zeppelins and the

patriotic fervor in the occupied capital at news that Romania was able to stop the

Central Powers' advance into

Moldavia.

[7]

He described this stage in his life as marked by an unrepeatable

epiphany.

[8][9] Recalling his entrance into a drawing room that an "eerie iridescent light" had turned into "a fairy-tale palace", he wrote,

I practiced for many years [the] exercise of recapturing that

epiphanic moment, and I would always find again the same plenitude. I

would slip into it as into a fragment of time devoid of duration—without

beginning, middle, or end. During my last years of lycée, when I

struggled with profound attacks of melancholy,

I still succeeded at times in returning to the golden green light of

that afternoon. [...] But even though the beatitude was the same, it was

now impossible to bear because it aggravated my sadness too much. By

this time I knew the world to which the drawing room belonged [...] was a

world forever lost.[10]

Robert Ellwood, a professor of religion who did his graduate studies under Mircea Eliade,

[11] saw this type of

nostalgia as one of the most characteristic themes in Eliade's life and academic writings.

[9]

Adolescence and literary debut

After completing his primary education at the school on Mântuleasa Street,

[2] Eliade attended the

Spiru Haret National College in the same class as

Arșavir Acterian,

Haig Acterian, and

Petre Viforeanu (and several years the senior of

Nicolae Steinhardt, who eventually became a close friend of Eliade's).

[12] Among his other colleagues was future philosopher

Constantin Noica[3] and Noica's friend, future art historian

Barbu Brezianu.

[13]

As a child, Eliade was fascinated with the natural world, which formed the setting of his very first literary attempts,

[3] as well as with

Romanian folklore and the

Christian faith as expressed by peasants.

[6] Growing up, he aimed to find and record what he believed was the common source of all religious traditions.

[6] The young Eliade's interest in physical exercise and adventure led him to pursue

mountaineering and

sailing,

[6] and he also joined the

Romanian Boy Scouts.

[14]

With a group of friends, he designed and sailed a boat on the

Danube, from

Tulcea to the

Black Sea.

[15]

In parallel, Eliade grew estranged from the educational environment,

becoming disenchanted with the discipline required and obsessed with the

idea that he was uglier and less virile than his colleagues.

[3] In order to cultivate his willpower, he would force himself to swallow insects

[3] and only slept four to five hours a night.

[7] At one point, Eliade was failing four subjects, among which was the study of the

Romanian language.

[3]

Instead, he became interested in

natural science and

chemistry, as well as the

occult,

[3] and wrote short pieces on

entomological subjects.

[7] Despite his father's concern that he was in danger of losing his already weak eyesight, Eliade read passionately.

[3] One of his favorite authors was

Honoré de Balzac, whose work he studied carefully.

[3][7] Eliade also became acquainted with the

modernist short stories of

Giovanni Papini and

social anthropology studies by

James George Frazer.

[7]

His interest in the two writers led him to learn Italian and English in private, and he also began studying

Persian and

Hebrew.

[2][7] At the time, Eliade became acquainted with

Saadi's poems and the ancient

Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh.

[7] He was also interested in philosophy—studying, among others,

Socrates,

Vasile Conta, and the

Stoics Marcus Aurelius and

Epictetus, and read works of history—the two Romanian historians who influenced him from early on were

Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu and

Nicolae Iorga.

[7] His first published work was the 1921

Inamicul viermelui de mătase ("The Silkworm's Enemy"),

[2] followed by

Cum am găsit piatra filosofală ("How I Found the

Philosophers' Stone").

[7] Four years later, Eliade completed work on his debut volume, the autobiographical

"Diary of a Short-Sighted Adolescent" translated into English and published by

Istros Books in 2016.

University studies and Indian sojourn

Between 1925 and 1928, he attended the

University of Bucharest's Faculty of Philosophy and Letters in 1928, earning his diploma with a study on Early Modern Italian philosopher

Tommaso Campanella.

[2] In 1927, Eliade traveled to Italy, where he met Papini

[2] and collaborated with the scholar

Giuseppe Tucci.

It was during his student years that Eliade met

Nae Ionescu, who lectured in

Logic, becoming one of his disciples and friends.

[3][6][16] He was especially attracted to Ionescu's radical ideas and his interest in religion, which signified a break with the

rationalist tradition represented by senior academics such as

Constantin Rădulescu-Motru,

Dimitrie Gusti, and

Tudor Vianu (all of whom owed inspiration to the defunct literary society

Junimea, albeit in varying degrees).

[3]

Eliade's scholarly works began after a long period of study in

British India, at the

University of Calcutta. Finding that the

Maharaja of

Kassimbazar

sponsored European scholars to study in India, Eliade applied and was

granted an allowance for four years, which was later doubled by a

Romanian

scholarship.

[17] In autumn 1928, he sailed for

Calcutta to study

Sanskrit and philosophy under

Surendranath Dasgupta, a

Bengali Cambridge alumnus and professor at Calcutta University, the author of a five volume

History of Indian Philosophy. Before reaching the

Indian subcontinent, Eliade also made a brief visit to Egypt.

[2] Once there, he visited large areas of the region, and spent a short period at a

Himalayan ashram.

[18]

He studied the basics of

Indian philosophy, and, in parallel, learned Sanskrit,

Pali and

Bengali under Dasgupta's direction.

[17] At the time, he also became interested in the actions of

Mahatma Gandhi, whom he met personally,

[19] and the

Satyagraha as a phenomenon; later, Eliade adapted Gandhian ideas in his discourse on spirituality and Romania.

[19]

In 1930, while living with Dasgupta, Eliade fell in love with his host's daughter,

Maitreyi Devi, later writing a barely disguised autobiographical novel

Maitreyi (also known as "La Nuit Bengali" or "Bengal Nights"), in which he claimed that he carried on a physical relationship with her.

[20]

Eliade received his

PhD in 1933, with a thesis on

Yoga practices.

[3][6][21][22] The book, which was translated into French three years later,

[17] had significant impact in academia, both in Romania and abroad.

[6]

He later recalled that the book was an early step for understanding

not just Indian religious practices, but also Romanian spirituality.

[23] During the same period, Eliade began a correspondence with the

Ceylonese-born philosopher

Ananda Coomaraswamy.

[24] In 1936–1937, he functioned as honorary assistant for Ionescu's course, lecturing in

Metaphysics.

[25]

In 1933, Mircea Eliade had a physical relationship with the actress

Sorana Țopa, while falling in love with Nina Mareș, whom he ultimately

married.

[5][6][26] The latter, introduced to him by his new friend

Mihail Sebastian, already had a daughter, Giza, from a man who had divorced her.

[6] Eliade subsequently adopted Giza,

[27] and the three of them moved to an apartment at 141

Dacia Boulevard.

[6] He left his residence in 1936, during a trip he made to the United Kingdom and Germany, when he first visited

London,

Oxford and

Berlin.

[2]

Criterion and Cuvântul

After contributing various and generally polemical pieces in university magazines, Eliade came to the attention of journalist

Pamfil Șeicaru, who invited him to collaborate on the

nationalist paper

Cuvântul, which was noted for its harsh tones.

[3] By then,

Cuvântul was also hosting articles by Ionescu.

[3]

As one of the figures in the

Criterion literary society (1933–1934), Eliade's initial encounter with the traditional

far right was polemical: the group's conferences were stormed by members of

A. C. Cuza's

National-Christian Defense League, who objected to what they viewed as

pacifism and addressed

antisemitic insults to several speakers, including Sebastian;

[28] in 1933, he was among the signers of a manifesto opposing

Nazi Germany's state-enforced

racism.

[29]

In 1934, at a time when Sebastian was publicly insulted by Nae Ionescu, who prefaced his book (

De două mii de ani...)

with thoughts on the "eternal damnation" of Jews, Mircea Eliade spoke

out against this perspective, and commented that Ionescu's references to

the verdict "

Outside the Church there is no salvation" contradicted the notion of God's

omnipotence.

[30][31] However, he contended that Ionescu's text was not evidence of antisemitism.

[32]

In 1936, reflecting on the early history of the

Romanian Kingdom and its

Jewish community, he deplored the expulsion of Jewish savants from Romanian soil, making specific references to

Moses Gaster,

Heimann Hariton Tiktin and

Lazăr Șăineanu.

[33] Eliade's views at the time focused on innovation—in the summer of 1933, he replied to an anti-

modernist critique written by

George Călinescu:

All I wish for is a deep change, a complete transformation. But, for God's sake, in any direction other than spirituality.[34]

He and friends

Emil Cioran and

Constantin Noica were by then under the influence of

Trăirism, a school of thought that was formed around the ideals expressed by Ionescu. A form of

existentialism,

Trăirism was also the synthesis of traditional and newer

right-wing beliefs.

[35] Early on, a public polemic was sparked between Eliade and

Camil Petrescu: the two eventually reconciled and later became good friends.

[27]

Like Mihail Sebastian, who was himself becoming influenced by

Ionescu, he maintained contacts with intellectuals from all sides of the

political spectrum: their entourage included the right-wing

Dan Botta and

Mircea Vulcănescu, the non-political Petrescu and

Ionel Jianu, and

Belu Zilber, who was a member of the illegal

Romanian Communist Party.

[36]

The group also included

Haig Acterian,

Mihail Polihroniade,

Petru Comarnescu,

Marietta Sadova and

Floria Capsali.

[30]

He was also close to

Marcel Avramescu, a former

Surrealist writer whom he introduced to the works of

René Guénon.

[37] A doctor in the

Kabbalah and future

Romanian Orthodox cleric, Avramescu joined Eliade in editing the short-lived

esoteric magazine

Memra (the only one of its kind in Romania).

[38]

Among the intellectuals who attended his lectures were

Mihail Şora (whom he deemed his favorite student),

Eugen Schileru and

Miron Constantinescu—known later as, respectively, a philosopher, an art critic, and a sociologist and political figure of the

communist regime.

[27] Mariana Klein, who became Șora's wife, was one of Eliade's female students, and later authored works on his scholarship.

[27]

Eliade later recounted that he had himself enlisted Zilber as a

Cuvântul contributor, in order for him to provide a

Marxist perspective on the issues discussed by the journal.

[36] Their relation soured in 1935, when the latter publicly accused Eliade of serving as an agent for the secret police,

Siguranța Statului

(Sebastian answered to the statement by alleging that Zilber was

himself a secret agent, and the latter eventually retracted his claim).

[36]

1930s political transition

Eliade's articles before and after his adherence to the principles of the

Iron Guard (or, as it was usually known at the time, the

Legionary Movement), beginning with his

Itinerar spiritual ("Spiritual Itinerary", serialized in

Cuvântul in 1927), center on several political ideals advocated by the far right.

They displayed his rejection of

liberalism and the

modernizing goals of the

1848 Wallachian revolution (perceived as "an abstract apology of Mankind"

[39] and "ape-like imitation of [Western] Europe"),

[40] as well as for

democracy itself (accusing it of "managing to crush all attempts at national renaissance",

[41] and later praising

Benito Mussolini's

Fascist Italy

on the grounds that, according to Eliade, "[in Italy,] he who thinks

for himself is promoted to the highest office in the shortest of

times").

[41] He approved of an

ethnic nationalist state centered on the Orthodox Church (in 1927, despite his still-vivid interest in

Theosophy, he recommended young

intellectuals "the return to the Church"),

[42] which he opposed to, among others, the

secular nationalism of

Constantin Rădulescu-Motru;

[43] referring to this particular ideal as "Romanianism", Eliade was, in 1934, still viewing it as "neither fascism, nor

chauvinism".

[44]

Eliade was especially dissatisfied with the incidence of unemployment

among intellectuals, whose careers in state-financed institutions had

been rendered uncertain by the

Great Depression.

[45]

In 1936, Eliade was the focus of a campaign in the far right press, being targeted for having authored "

pornography" in his

Domnișoara Christina and

Isabel și apele diavolului; similar accusations were aimed at other cultural figures, including

Tudor Arghezi and

Geo Bogza.

[46] Assessments of Eliade's work were in sharp contrast to one another: also in 1936, Eliade accepted an award from the

Romanian Writers' Society, of which he had been a member since 1934.

[47]

In summer 1937, through an official decision which came as a result of

the accusations, and despite student protests, he was stripped of his

position at the University.

[48]

Eliade decided to sue the

Ministry of Education, asking for a symbolic compensation of 1

leu.

[49] He won the trial, and regained his position as Nae Ionescu's assistant.

[49]

Nevertheless, by 1937, he gave his intellectual support to the Iron Guard, in which he saw "a

Christian revolution aimed at creating a new Romania",

[50] and a group able "to reconcile Romania with God".

[50] His articles of the time, published in Iron Guard papers such as

Sfarmă Piatră and

Buna Vestire, contain ample praises of the movement's leaders (

Corneliu Zelea Codreanu,

Ion Moţa,

Vasile Marin, and

Gheorghe Cantacuzino-Grănicerul).

[51][52]

The transition he went through was similar to that of his fellow

generation members and close collaborators—among the notable exceptions

to this rule were

Petru Comarnescu, sociologist

Henri H. Stahl and future dramatist

Eugène Ionesco, as well as Sebastian.

[53]

He eventually enrolled in the

Totul pentru Țară ("Everything for the Fatherland" Party), the political expression of the Iron Guard,

[3][54] and contributed to its

1937 electoral campaign in

Prahova County—as indicated by his inclusion on a list of party members with

county-level responsibilities (published in

Buna Vestire).

[54]

Internment and diplomatic service

The stance taken by Eliade resulted in his arrest on July 14, 1938 after a crackdown on the Iron Guard authorized by

King Carol II. At the time of his arrest, he had just interrupted a column on

Provincia și legionarismul ("The Province and Legionary Ideology") in

Vremea, having been singled out by

Prime Minister Armand Călinescu as an author of Iron Guard

propaganda.

[55]

Eliade was kept for three weeks in a cell at the

Siguranţa Statului Headquarters, in an attempt to have him sign a "declaration of dissociation" with the Iron Guard, but he refused to do so.

[56] In the first week of August he was transferred to a makeshift camp at

Miercurea-Ciuc. When Eliade began coughing blood in October 1938, he was taken to a clinic in

Moroeni.

[56] Eliade was simply released on November 12, and subsequently spent his time writing his play

Iphigenia (also known as

Ifigenia).

[30] In April 1940, with the help of

Alexandru Rosetti, became the Cultural Attaché to the United Kingdom, a posting cut short when Romanian-British foreign relations were broken.

[56]

After leaving London he was assigned the office of Counsel and

Press Officer (later Cultural Attaché) to the Romanian Embassy in Portugal,

[26][57][58][59] where he was kept on as diplomat by the

National Legionary State (the Iron Guard government) and, ultimately, by

Ion Antonescu's regime. His office involved disseminating propaganda in favor of the Romanian state.

[26] In February 1941, weeks after the bloody

Legionary Rebellion was crushed by Antonescu,

Iphigenia was staged by the

National Theater Bucharest—the

play soon raised doubts that it owed inspiration to the Iron Guard's

ideology, and even that its inclusion in the program was a Legionary

attempt at subversion.

[30]

In 1942, Eliade authored a volume in praise of the

Estado Novo, established in Portugal by

António de Oliveira Salazar,

[59][60][61] claiming that "The Salazarian state, a Christian and

totalitarian one, is first and foremost based on love".

[60]

On July 7 of the same year, he was received by Salazar himself, who

assigned Eliade the task of warning Antonescu to withdraw the

Romanian Army from the

Eastern Front ("[In his place], I would not be grinding it in Russia").

[62] Eliade also claimed that such contacts with the leader of a neutral country had made him the target for

Gestapo surveillance, but that he had managed to communicate Salazar's advice to

Mihai Antonescu, Romania's

Foreign Minister.

[19][62]

In autumn 1943, he traveled to

occupied France, where he rejoined

Emil Cioran, also meeting with scholar

Georges Dumézil and the

collaborationist writer

Paul Morand.

[26] At the same time, he applied for a position of lecturer at the

University of Bucharest, but withdrew from the race, leaving

Constantin Noica and

Ion Zamfirescu to dispute the position, in front of a panel of academics comprising

Lucian Blaga and

Dimitrie Gusti (Zamfirescu's eventual selection, going against Blaga's recommendation, was to be the topic of a controversy).

[63]

In his private notes, Eliade wrote that he took no further interest in

the office, because his visits abroad had convinced him that he had

"something great to say", and that he could not function within the

confines of "a minor culture".

[26] Also during the war, Eliade traveled to

Berlin, where he met and conversed with controversial political theorist

Carl Schmitt,

[6][26] and frequently visited

Francoist Spain, where he notably attended the 1944 Lusitano-Spanish scientific congress in

Córdoba.

[26][64][65] It was during his trips to Spain that Eliade met philosophers

José Ortega y Gasset and

Eugeni d'Ors. He maintained a friendship with d'Ors, and met him again on several occasions after the war.

[64]

Nina Eliade fell ill with

uterine cancer and died during their stay in

Lisbon, in late 1944. As the widower later wrote, the disease was probably caused by an

abortion procedure she had undergone at an early stage of their relationship.

[26] He came to suffer from

clinical depression, which increased as Romania and her

Axis allies suffered major defeats on the Eastern Front.

[26][65] Contemplating a return to Romania as a soldier or a

monk,

[26] he was on a continuous search for effective

antidepressants, medicating himself with

passion flower extract, and, eventually, with

methamphetamine.

[65]

This was probably not his first experience with drugs: vague mentions

in his notebooks have been read as indication that Mircea Eliade was

taking

opium during his travels to

Calcutta.

[65] Later, discussing the works of

Aldous Huxley, Eliade wrote that the British author's use of

mescaline

as a source of inspiration had something in common with his own

experience, indicating 1945 as a date of reference and adding that it

was "needless to explain why that is".

[65]

Early exile

At signs that the

Romanian communist regime

was about to take hold, Eliade opted not to return to the country. On

September 16, 1945, he moved to France with his adopted daughter Giza.

[2][26] Once there, he resumed contacts with Dumézil, who helped him recover his position in academia.

[6] On Dumézil's recommendation, he taught at the

École Pratique des Hautes Études in

Paris.

[27] It was estimated that, at the time, it was not uncommon for him to work 15 hours a day.

[22] Eliade married a second time, to the Romanian exile Christinel Cotescu.

[6][66] His second wife, the descendant of

boyars, was the sister-in-law of the conductor

Ionel Perlea.

[66]

Together with

Emil Cioran and other Romanian expatriates, Eliade rallied with the former diplomat

Alexandru Busuioceanu, helping him publicize

anti-communist opinion to the

Western European public.

[67] He was also briefly involved in publishing a Romanian-language magazine, titled

Luceafărul ("The Morning Star"),

[67] and was again in contact with

Mihail Șora, who had been granted a

scholarship to study in France, and with Șora's wife

Mariana.

[27] In 1947, he was facing material constraints, and

Ananda Coomaraswamy found him a job as a

French-language teacher in the United States, at a school in

Arizona; the arrangement ended upon Coomaraswamy's death in September.

[24]

Beginning in 1948, he wrote for the journal

Critique, edited by French philosopher

Georges Bataille.

[2] The following year, he went on a visit to Italy, where he wrote the first 300 pages of his novel

Noaptea de Sânziene (he visited the country a third time in 1952).

[2] He collaborated with

Carl Jung and the

Eranos circle after

Henry Corbin recommended him in 1949,

[24] and wrote for the

Antaios magazine (edited by

Ernst Jünger).

[22] In 1950, Eliade began attending

Eranos conferences, meeting Jung,

Olga Fröbe-Kapteyn,

Gershom Scholem and

Paul Radin.

[68] He described

Eranos as "one of the most creative cultural experiences of the modern Western world."

[69]

In October 1956, he moved to the United States, settling in

Chicago the following year.

[2][6] He had been invited by

Joachim Wach to give a series of lectures at Wach's home institution, the

University of Chicago.

[69]

Eliade and Wach are generally admitted to be the founders of the

"Chicago school" that basically defined the study of religions for the

second half of the 20th century.

[70] Upon Wach's death before the lectures were delivered, Eliade was appointed as his replacement, becoming, in 1964, the

Sewell Avery Distinguished Service Professor of the History of Religions.

[2] Beginning in 1954, with the first edition of his volume on

Eternal Return,

Eliade also enjoyed commercial success: the book went through several

editions under different titles, which sold over 100,000 copies.

[71]

In 1966, Mircea Eliade became a member of the

American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

[2] He also worked as editor-in-chief of

Macmillan Publishers'

Encyclopedia of Religion, and, in 1968, lectured in religious history at the

University of California, Santa Barbara.

[72] It was also during that period that Mircea Eliade completed his voluminous and influential

History of Religious Ideas, which grouped together the overviews of his main original interpretations of religious history.

[6] He occasionally traveled out of the United States, such as attending the Congress for the History of Religions in

Marburg (1960) and visits to Sweden and Norway in 1970.

[2]

Final years and death

Initially, Eliade was attacked with virulence by the

Romanian Communist Party press, chiefly by

România Liberă—which described him as "the Iron Guard's ideologue,

enemy of the working class, apologist of Salazar's dictatorship".

[73] However, the regime also made secretive attempts to enlist his and Cioran's support:

Haig Acterian's widow, theater director

Marietta Sadova, was sent to Paris in order to re-establish contacts with the two.

[74]

Although the move was planned by Romanian officials, her encounters

were to be used as evidence incriminating her at a February 1960 trial

for treason (where

Constantin Noica and

Dinu Pillat were the main defendants).

[74] Romania's secret police, the

Securitate, also portrayed Eliade as a spy for the British

Secret Intelligence Service and a former agent of the Gestapo.

[75]

He was slowly

rehabilitated at home beginning in the early 1960s, under the rule of

Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej.

[76] In the 1970s, Eliade was approached by the

Nicolae Ceaușescu regime in several ways, in order to have him return.

[6] The move was prompted by the officially sanctioned nationalism and Romania's claim to independence from the

Eastern Bloc,

as both phenomena came to see Eliade's prestige as an asset. An

unprecedented event occurred with the interview that was granted by

Mircea Eliade to poet

Adrian Păunescu,

during the latter's 1970 visit to Chicago; Eliade complimented both

Păunescu's activism and his support for official tenets, expressing a

belief that

the youth of Eastern Europe is clearly superior to that of Western

Europe. [...] I am convinced that, within ten years, the young

revolutionary generation shan't be behaving as does today the noisy

minority of Western contesters.

[...] Eastern youth have seen the abolition of traditional

institutions, have accepted it [...] and are not yet content with the

structures enforced, but rather seek to improve them.[77]

Păunescu's visit to Chicago was followed by those of the nationalist official writer

Eugen Barbu and by Eliade's friend Constantin Noica (who had since been released from jail).

[52]

At the time, Eliade contemplated returning to Romania, but was

eventually persuaded by fellow Romanian intellectuals in exile

(including

Radio Free Europe's

Virgil Ierunca and

Monica Lovinescu) to reject Communist proposals.

[52]

In 1977, he joined other exiled Romanian intellectuals in signing a

telegram protesting the repressive measures newly enforced by the

Ceauşescu regime.

[3] Writing in 2007, Romanian anthropologist

Andrei Oișteanu recounted how, around 1984, the Securitate unsuccessfully pressured to become an

agent of influence in Eliade's Chicago circle.

[78]

During his later years, Eliade's fascist past was progressively

exposed publicly, the stress of which probably contributed to the

decline of his health.

[3] By then, his writing career was hampered by severe

arthritis.

[27] The last academic honors bestowed upon him were the

French Academy's

Bordin Prize (1977) and the title of

Doctor Honoris Causa, granted by the

University of Washington (1985).

[2]

Mircea Eliade died at the

Bernard Mitchell Hospital in April 1986. Eight days previously, he suffered a

stroke while reading

Emil Cioran's

Exercises of Admiration, and had subsequently lost his speech function.

[8] Four months before, a fire had destroyed part of his office at the

Meadville Lombard Theological School (an event which he had interpreted as an

omen).

[3][8] Eliade's Romanian disciple

Ioan Petru Culianu, who recalled the scientific community's reaction to the news, described Eliade's death as "a

mahaparanirvana", thus comparing it to the passing of

Gautama Buddha.

[8] His body was

cremated in Chicago, and the funeral ceremony was held on University grounds, at the

Rockefeller Chapel.

[2][8] It was attended by 1,200 people, and included a public reading of Eliade's text in which he recalled the

epiphany of his childhood—the lecture was given by novelist

Saul Bellow, Eliade's colleague at the University.

[8] His grave is located in

Oak Woods Cemetery.

[79]

Work

The general nature of religion

In his work on the history of religion, Eliade is most highly regarded for his writings on

Alchemy,

[80] Shamanism,

Yoga and what he called the

eternal return—the implicit belief, supposedly present in religious thought in general, that

religious behavior

is not only an imitation of, but also a participation in, sacred

events, and thus restores the mythical time of origins. Eliade's

thinking was in part influenced by

Rudolf Otto,

Gerardus van der Leeuw,

Nae Ionescu and the writings of the

Traditionalist School (

René Guénon and

Julius Evola).

[37] For instance, Eliade's

The Sacred and the Profane partially builds on Otto's

The Idea of the Holy to show how religion emerges from the experience of the sacred, and myths of time and nature.

Eliade is known for his attempt to find broad, cross-cultural parallels and unities in religion, particularly in myths.

Wendy Doniger,

Eliade's colleague from 1978 until his death, has observed that "Eliade

argued boldly for universals where he might more safely have argued for

widely prevalent patterns".

[81] His

Treatise on the History of Religions was praised by French philologist

Georges Dumézil for its coherence and ability to synthesize diverse and distinct mythologies.

[82]

Robert Ellwood describes Eliade's approach to religion as follows.

Eliade approaches religion by imagining an ideally "religious" person,

whom he calls

homo religiosus in his writings. Eliade's theories basically describe how this

homo religiosus would view the world.

[83] This does not mean that all religious practitioners actually think and act like

homo religiosus. Instead, it means that religious behavior "says through its own language" that the world is as

homo religiosus would see it, whether or not the real-life participants in religious behavior are aware of it.

[84]

However, Ellwood writes that Eliade "tends to slide over that last

qualification", implying that traditional societies actually thought

like

homo religiosus.

[84]

Sacred and profane

Eliade argues that religious thought in general rests on a sharp distinction between the Sacred and the profane;

[85]

whether it takes the form of God, gods, or mythical Ancestors, the

Sacred contains all "reality", or value, and other things acquire

"reality" only to the extent that they participate in the sacred.

[86]

Eliade's understanding of religion centers on his concept of

hierophany (manifestation of the Sacred)—a concept that includes, but is not limited to, the older and more restrictive concept of

theophany (manifestation of a god).

[87]

From the perspective of religious thought, Eliade argues, hierophanies

give structure and orientation to the world, establishing a sacred

order. The "profane" space of nonreligious experience can only be

divided up geometrically: it has no "qualitative differentiation and,

hence, no orientation [is] given by virtue of its inherent structure".

[88]

Thus, profane space gives man no pattern for his behavior. In contrast

to profane space, the site of a hierophany has a sacred structure to

which religious man conforms himself. A hierophany amounts to a

"revelation of an absolute reality, opposed to the non-reality of the

vast surrounding expanse".

[89] As an example of "

sacred space" demanding a certain response from man, Eliade gives the story of

Moses halting before

Yahweh's manifestation as a

burning bush (

Exodus 3:5) and taking off his shoes.

[90]

Origin myths and sacred time

Eliade notes that, in traditional societies, myth represents the absolute truth about primordial time.

[91]

According to the myths, this was the time when the Sacred first

appeared, establishing the world's structure—myths claim to describe the

primordial events that made society and the natural world be that which

they are. Eliade argues that all myths are, in that sense, origin

myths: "myth, then, is always an account of a

creation".

[92]

Many traditional societies believe that the power of a thing lies in its origin.

[93] If origin is equivalent to power, then "it is the first manifestation of a thing that is significant and valid"

[94] (a thing's reality and value therefore lies only in its first appearance).

According to Eliade's theory, only the Sacred has value, only a

thing's first appearance has value and, therefore, only the Sacred's

first appearance has value. Myth describes the Sacred's first

appearance; therefore, the mythical age is sacred time,

[91] the only time of value: "primitive man was interested only in the

beginnings [...] to him it mattered little what had happened to himself, or to others like him, in more or less distant times".

[95] Eliade postulated this as the reason for the "

nostalgia for origins" that appears in many religions, the desire to return to a primordial

Paradise.

[95]

Eternal return and "Terror of history"

Eliade argues that traditional man attributes no value to the linear

march of historical events: only the events of the mythical age have

value. To give his own life value, traditional man performs myths and

rituals. Because the Sacred's essence lies only in the mythical age,

only in the Sacred's first appearance, any later appearance is actually

the first appearance; by recounting or re-enacting mythical events,

myths and rituals "re-actualize" those events.

[96] Eliade often uses the term "

archetypes"

to refer to the mythical models established by the Sacred, although

Eliade's use of the term should be distinguished from the use of the

term in

Jungian psychology.

[97]

Thus, argues Eliade, religious behavior does not only commemorate, but also participates in, sacred events:

In imitating the exemplary acts of a god or of a mythical

hero, or simply by recounting their adventures, the man of an archaic

society detaches himself from profane time and magically re-enters the

Great Time, the sacred time.[91]

Eliade called this concept the "

eternal return" (distinguished from the

philosophical concept of "eternal return"). Wendy Doniger noted that Eliade's theory of the eternal return "has become a truism in the study of religions".

[1]

Eliade attributes the well-known "cyclic" vision of time in ancient thought to belief in the eternal return. For instance, the

New Year ceremonies among the

Mesopotamians, the

Egyptians, and other

Near Eastern peoples re-enacted their

cosmogonic myths. Therefore, by the logic of the eternal return, each New Year ceremony

was

the beginning of the world for these peoples. According to Eliade,

these peoples felt a need to return to the Beginning at regular

intervals, turning time into a circle.

[98]

Eliade argues that yearning to remain in the mythical age causes a

"terror of history": traditional man desires to escape the linear

succession of events (which, Eliade indicated, he viewed as empty of any

inherent value or sacrality). Eliade suggests that the abandonment of

mythical thought and the full acceptance of linear, historical time,

with its "terror", is one of the reasons for modern man's anxieties.

[99] Traditional societies escape this anxiety to an extent, as they refuse to completely acknowledge historical time.

Coincidentia oppositorum

Eliade claims that many myths, rituals, and mystical experiences involve a "coincidence of opposites", or

coincidentia oppositorum. In fact, he calls the

coincidentia oppositorum "the mythical pattern".

[100] Many myths, Eliade notes, "present us with a twofold revelation":

they express on the one hand the diametrical opposition of two divine

figures sprung from one and the same principle and destined, in many

versions, to be reconciled at some illud tempus of eschatology, and on the other, the coincidentia oppositorum

in the very nature of the divinity, which shows itself, by turns or

even simultaneously, benevolent and terrible, creative and destructive,

solar and serpentine, and so on (in other words, actual and potential).[101]

Eliade argues that "Yahweh is both kind and wrathful; the God of the

Christian mystics and theologians is terrible and gentle at once".

[102]

He also thought that the Indian and Chinese mystic tried to attain "a

state of perfect indifference and neutrality" that resulted in a

coincidence of opposites in which "pleasure and pain, desire and

repulsion, cold and heat [...] are expunged from his awareness".

[102]

According to Eliade, the

coincidentia oppositorum’s appeal lies in "man's deep dissatisfaction with his actual situation, with what is called the human condition".

[103] In many mythologies, the end of the mythical age involves a "fall", a fundamental "

ontological change in the structure of the World".

[104] Because the

coincidentia oppositorum is a contradiction, it represents a denial of the world's current logical structure, a reversal of the "fall".

Also, traditional man's dissatisfaction with the post-mythical age expresses itself as a feeling of being "torn and separate".

[103]

In many mythologies, the lost mythical age was a Paradise, "a

paradoxical state in which the contraries exist side by side without

conflict, and the multiplications form aspects of a mysterious Unity".

[104] The

coincidentia oppositorum

expresses a wish to recover the lost unity of the mythical Paradise,

for it presents a reconciliation of opposites and the unification of

diversity:

On the level of pre-systematic thought, the mystery of totality

embodies man's endeavor to reach a perspective in which the contraries

are abolished, the Spirit of Evil reveals itself as a stimulant of Good,

and Demons appear as the night aspect of the Gods.[104]

Exceptions to the general nature

Eliade acknowledges that not all religious behavior has all the

attributes described in his theory of sacred time and the eternal

return. The

Zoroastrian,

Jewish,

Christian, and

Muslim traditions embrace linear, historical time as sacred or capable of sanctification, while some

Eastern traditions largely reject the notion of sacred time, seeking escape from the

cycles of time.

Because they contain rituals, Judaism and Christianity necessarily—Eliade argues—retain a sense of cyclic time:

by the very fact that it is a religion, Christianity had to keep at least one mythical aspect—liturgical Time, that is, the periodic rediscovery of the illud tempus of the beginnings [and] an imitation of the Christ as exemplary pattern.[105]

However, Judaism and Christianity do not see time as a circle

endlessly turning on itself; nor do they see such a cycle as desirable,

as a way to participate in the Sacred. Instead, these religions embrace

the concept of linear history progressing toward the

Messianic Age or the

Last Judgment, thus initiating the idea of "progress" (humans are to work for a Paradise in the future).

[106] However, Eliade's understanding of Judaeo-Christian

eschatology

can also be understood as cyclical in that the "end of time" is a

return to God: "The final catastrophe will put an end to history, hence

will restore man to eternity and beatitude".

[107]

The pre-

Islamic Persian religion of Zoroastrianism, which made a notable "contribution to the religious formation of the West",

[108]

also has a linear sense of time. According to Eliade, the Hebrews had a

linear sense of time before being influenced by Zoroastrianism.

[108]

In fact, Eliade identifies the Hebrews, not the Zoroastrians, as the

first culture to truly "valorize" historical time, the first to see all

major historical events as episodes in a continuous divine revelation.

[109]

However, Eliade argues, Judaism elaborated its mythology of linear time

by adding elements borrowed from Zoroastrianism—including

ethical dualism, a savior figure, the future resurrection of the body, and the idea of cosmic progress toward "the final triumph of Good".

[108]

The

Indian religions of the East generally retain a cyclic view of time—for instance, the

Hindu doctrine of

kalpas.

According to Eliade, most religions that accept the cyclic view of time

also embrace it: they see it as a way to return to the sacred time.

However, in

Buddhism,

Jainism, and some forms of Hinduism, the Sacred lies outside the flux of the material world (called

maya, or "illusion"), and one can only reach it by escaping from the cycles of time.

[110] Because the Sacred lies outside cyclic time, which conditions humans, people can only reach the Sacred by escaping the

human condition. According to Eliade,

Yoga techniques aim at escaping the limitations of the body, allowing the soul (

atman) to rise above

maya and reach the Sacred (

nirvana,

moksha).

Imagery of "freedom", and of death to one's old body and rebirth with a

new body, occur frequently in Yogic texts, representing escape from the

bondage of the temporal human condition.

[111] Eliade discusses these themes in detail in

Yoga: Immortality and Freedom.

Symbolism of the Center

A recurrent theme in Eliade's myth analysis is the

axis mundi,

the Center of the World. According to Eliade, the Cosmic Center is a

necessary corollary to the division of reality into the Sacred and the

profane. The Sacred contains all value, and the world gains purpose and

meaning only through hierophanies:

In the homogeneous and infinite expanse, in which no point of

reference is possible and hence no orientation is established, the hierophany reveals an absolute fixed point, a center.[89]

Because profane space gives man no orientation for his life, the

Sacred must manifest itself in a hierophany, thereby establishing a

sacred site around which man can orient himself. The site of a

hierophany establishes a "fixed point, a center".

[112] This Center abolishes the "homogeneity and relativity of profane space",

[88] for it becomes "the central axis for all future orientation".

[89]

A manifestation of the Sacred in profane space is, by definition, an

example of something breaking through from one plane of existence to

another. Therefore, the initial hierophany that establishes the Center

must be a point at which there is contact between different planes—this,

Eliade argues, explains the frequent mythical imagery of a

Cosmic Tree or Pillar joining Heaven, Earth, and the

underworld.

[113]

Eliade noted that, when traditional societies found a new territory,

they often perform consecrating rituals that reenact the hierophany that

established the Center and founded the world.

[114] In addition, the designs of traditional buildings, especially temples, usually imitate the mythical image of the

axis mundi joining the different cosmic levels. For instance, the

Babylonian ziggurats were built to resemble cosmic mountains passing through the heavenly spheres, and the rock of the

Temple in Jerusalem was supposed to reach deep into the

tehom, or primordial waters.

[115]

According to the logic of the

eternal return, the site of each such symbolic Center will actually be the Center of the World:

It may be said, in general, that the majority of the sacred and

ritual trees that we meet with in the history of religions are only

replicas, imperfect copies of this exemplary archetype, the Cosmic Tree.

Thus, all these sacred trees are thought of as situated at the Centre

of the World, and all the ritual trees or posts [...] are, as it were,

magically projected into the Centre of the World.[116]

According to Eliade's interpretation, religious man apparently feels the need to live not only near, but

at, the mythical Center as much as possible, given that the Center is the point of communication with the Sacred.

[117]

Thus, Eliade argues, many traditional societies share common outlines in their mythical

geographies. In the middle of the known world is the sacred Center, "a place that is sacred above all";

[118] this Center anchors the established order.

[88]

Around the sacred Center lies the known world, the realm of established

order; and beyond the known world is a chaotic and dangerous realm,

"peopled by ghosts, demons, [and] 'foreigners' (who are [identified

with] demons and the souls of the dead)".

[119]

According to Eliade, traditional societies place their known world at

the Center because (from their perspective) their known world is the

realm that obeys a recognizable order, and it therefore must be the

realm in which the Sacred manifests itself; the regions beyond the known

world, which seem strange and foreign, must lie far from the Center,

outside the order established by the Sacred.

[120]

The High God

According to some "evolutionistic" theories of religion, especially that of

Edward Burnett Tylor, cultures naturally progress from

animism and

polytheism to

monotheism.

[121]

According to this view, more advanced cultures should be more

monotheistic, and more primitive cultures should be more polytheistic.

However, many of the most "primitive", pre-agricultural societies

believe in a supreme

sky-god.

[122] Thus, according to Eliade, post-19th-century scholars have rejected Tylor's theory of evolution from

animism.

[123]

Based on the discovery of supreme sky-gods among "primitives", Eliade

suspects that the earliest humans worshiped a heavenly Supreme Being.

[124] In

Patterns in Comparative Religion,

he writes, "The most popular prayer in the world is addressed to 'Our

Father who art in heaven.' It is possible that man's earliest prayers

were addressed to the same heavenly father."

[125]

However, Eliade disagrees with

Wilhelm Schmidt, who thought the earliest form of religion was a strict monotheism. Eliade dismisses this theory of "primordial monotheism" (

Urmonotheismus) as "rigid" and unworkable.

[126] "At most," he writes, "this schema [Schmidt's theory] renders an account of human [religious] evolution since the

Paleolithic era".

[127] If an

Urmonotheismus

did exist, Eliade adds, it probably differed in many ways from the

conceptions of God in many modern monotheistic faiths: for instance, the

primordial High God could manifest himself as an animal without losing

his status as a celestial Supreme Being.

[128]

According to Eliade, heavenly Supreme Beings are actually less common in more advanced cultures.

[129] Eliade speculates that the discovery of agriculture brought a host of

fertility gods and goddesses into the forefront, causing the celestial Supreme Being to fade away and eventually vanish from many ancient religions.

[130] Even in primitive hunter-gatherer societies, the High God is a vague, distant figure, dwelling high above the world.

[131] Often he has no

cult and receives

prayer only as a last resort, when all else has failed.

[132] Eliade calls the distant High God a

deus otiosus ("idle god").

[133]

In belief systems that involve a

deus otiosus, the distant

High God is believed to have been closer to humans during the mythical

age. After finishing his works of creation, the High God "forsook the

earth and withdrew into the highest heaven".

[134]

This is an example of the Sacred's distance from "profane" life, life

lived after the mythical age: by escaping from the profane condition

through religious behavior, figures such as the

shaman return to the conditions of the mythical age, which include nearness to the High God ("by his

flight or ascension, the shaman [...] meets the God of Heaven face to face and speaks directly to him, as man sometimes did

in illo tempore").

[135] The shamanistic behaviors surrounding the High God are a particularly clear example of the eternal return.

Shamanism

Overview

Eliade's scholarly work includes a study of shamanism,

Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, a survey of shamanistic practices in different areas. His

Myths, Dreams and Mysteries also addresses shamanism in some detail.

In

Shamanism, Eliade argues for a restrictive use of the word

shaman: it should not apply to just any

magician or

medicine man,

as that would make the term redundant; at the same time, he argues

against restricting the term to the practitioners of the sacred of

Siberia and

Central Asia (it is from one of the titles for this function, namely,

šamán, considered by Eliade to be of

Tungusic origin, that the term itself was introduced into Western languages).

[136] Eliade defines a shaman as follows:

he is believed to cure, like all doctors, and to perform miracles of the fakir type, like all magicians [...] But beyond this, he is a psychopomp, and he may also be a priest, mystic, and poet.[137]

If we define shamanism this way, Eliade claims, we find that the term

covers a collection of phenomena that share a common and unique

"structure" and "history".

[137] (When thus defined, shamanism tends to occur in its purest forms in

hunting and

pastoral societies like those of Siberia and Central Asia, which revere a celestial High God "on the way to becoming a

deus otiosus".

[138] Eliade takes the shamanism of those regions as his most representative example.)

In his examinations of shamanism, Eliade emphasizes the shaman's

attribute of regaining man's condition before the "Fall" out of sacred

time: "The most representative mystical experience of the archaic

societies, that of shamanism, betrays the

Nostalgia for Paradise, the desire to recover the state of freedom and beatitude before 'the Fall'."

[135]

This concern—which, by itself, is the concern of almost all religious

behavior, according to Eliade—manifests itself in specific ways in

shamanism.

Death, resurrection and secondary functions

According to Eliade, one of the most common shamanistic themes is the shaman's supposed death and

resurrection. This occurs in particular during his

initiation.

[139]

Often, the procedure is supposed to be performed by spirits who

dismember the shaman and strip the flesh from his bones, then put him

back together and revive him. In more than one way, this death and

resurrection represents the shaman's elevation above human nature.

First, the shaman dies so that he can rise above human nature on a

quite literal level. After he has been dismembered by the initiatory

spirits, they often replace his old organs with new, magical ones (the

shaman dies to his profane self so that he can rise again as a new,

sanctified, being).

[140]

Second, by being reduced to his bones, the shaman experiences rebirth

on a more symbolic level: in many hunting and herding societies, the

bone represents the source of life, so reduction to a skeleton "is

equivalent to re-entering the womb of this primordial life, that is, to a

complete renewal, a mystical rebirth".

[141] Eliade considers this return to the source of life essentially equivalent to the eternal return.

[142]

Third, the shamanistic phenomenon of repeated death and resurrection

also represents a transfiguration in other ways. The shaman dies not

once but many times: having died during initiation and risen again with

new powers, the shaman can send his spirit out of his body on errands;

thus, his whole career consists of repeated deaths and resurrections.

The shaman's new ability to die and return to life shows that he is no

longer bound by the laws of profane time, particularly the law of death:

"the ability to 'die' and come to life again [...] denotes that [the

shaman] has surpassed the human condition".

[143]

Having risen above the human condition, the shaman is not bound by

the flow of history. Therefore, he enjoys the conditions of the mythical

age. In many myths, humans can speak with animals; and, after their

initiations, many shamans claim to be able to communicate with animals.

According to Eliade, this is one manifestation of the shaman's return to

"the

illud tempus described to us by the paradisiac myths".

[144]

The shaman can descend to the underworld or ascend to heaven, often by climbing the

World Tree, the cosmic pillar, the sacred ladder, or some other form of the

axis mundi.

[145]

Often, the shaman will ascend to heaven to speak with the High God.

Because the gods (particularly the High God, according to Eliade's

deus otiosus

concept) were closer to humans during the mythical age, the shaman's

easy communication with the High God represents an abolition of history

and a return to the mythical age.

[135]

Because of his ability to communicate with the gods and descend to the land of the dead, the shaman frequently functions as a

psychopomp and a

medicine man.

[137]

Eliade's philosophy

Early contributions

In

addition to his political essays, the young Mircea Eliade authored

others, philosophical in content. Connected with the ideology of

Trăirism, they were often prophetic in tone, and saw Eliade being hailed as a herald by various representatives of his generation.

[7] When Eliade was 21 years old and publishing his

Itinerar spiritual, literary critic

Şerban Cioculescu described him as "the column leader of the spiritually mystical and

Orthodox youth."

[7]

Cioculescu discussed his "impressive erudition", but argued that it was

"occasionally plethoric, poetically inebriating itself through abuse".

[7] Cioculescu's colleague

Perpessicius

saw the young author and his generation as marked by "the specter of

war", a notion he connected to various essays of the 1920s and 30s in

which Eliade threatened the world with the verdict that a new conflict

was looming (while asking that young people be allowed to manifest their

will and fully experience freedom before perishing).

[7]

One of Eliade's noted contributions in this respect was the 1932

Soliloquii ("Soliloquies"), which explored

existential philosophy.

George Călinescu who saw in it "an echo of

Nae Ionescu's lectures",

[146] traced a parallel with the essays of another of Ionescu's disciples,

Emil Cioran, while noting that Cioran's were "of a more exulted tone and written in the

aphoristic form of

Kierkegaard".

[147] Călinescu recorded Eliade's rejection of

objectivity,

citing the author's stated indifference towards any "naïveté" or

"contradictions" that the reader could possibly reproach him, as well as

his dismissive thoughts of "theoretical data" and mainstream philosophy

in general (Eliade saw the latter as "inert, infertile and

pathogenic").

[146] Eliade thus argued, "a sincere brain is unassailable, for it denies itself to any relationship with outside truths."

[148]

The young writer was however careful to clarify that the existence he

took into consideration was not the life of "instincts and personal

idiosyncrasies", which he believed determined the lives of many humans, but that of a distinct set comprising "personalities".

[148] He described "personalities" as characterized by both "purpose" and "a much more complicated and dangerous alchemy".

[148]

This differentiation, George Călinescu believed, echoed Ionescu's

metaphor of man, seen as "the only animal who can fail at living", and

the duck, who "shall remain a duck no matter what it does".

[149]

According to Eliade, the purpose of personalities is infinity:

"consciously and gloriously bringing [existence] to waste, into as many

skies as possible, continuously fulfilling and polishing oneself,

seeking ascent and not circumference."

[148]

In Eliade's view, two roads await man in this process. One is glory,

determined by either work or procreation, and the other the

asceticism of religion or magic—both, Călinescu believed, where aimed at reaching the

absolute, even in those cases where Eliade described the latter as an "abyssal experience" into which man may take the plunge.

[146]

The critic pointed out that the addition of "a magical solution" to the

options taken into consideration seemed to be Eliade's own original

contributions to his mentor's philosophy, and proposed that it may have

owed inspiration to

Julius Evola and his disciples.

[146]

He also recorded that Eliade applied this concept to human creation,

and specifically to artistic creation, citing him describing the latter

as "a magical joy, the victorious break of the iron circle" (a

reflection of

imitatio dei, having salvation for its ultimate goal).

[146]

Philosopher of religion

Anti-reductionism and the "transconscious"

By

profession, Eliade was a historian of religion. However, his scholarly

works draw heavily on philosophical and psychological terminology. In

addition, they contain a number of philosophical arguments about

religion. In particular, Eliade often implies the existence of a

universal psychological or spiritual "essence" behind all religious

phenomena.

[150] Because of these arguments, some have accused Eliade of over-generalization and "

essentialism",

or even of promoting a theological agenda under the guise of historical

scholarship. However, others argue that Eliade is better understood as a

scholar who is willing to openly discuss sacred experience and its

consequences.

[151]

In studying religion, Eliade rejects certain "

reductionist" approaches.

[152]

Eliade thinks a religious phenomenon cannot be reduced to a product of

culture and history. He insists that, although religion involves "the

social man, the economic man, and so forth", nonetheless "all these

conditioning factors together do not, of themselves, add up to the life

of the spirit".

[153]

Using this anti-reductionist position, Eliade argues against those who accuse him of overgeneralizing, of looking for

universals at the expense of

particulars. Eliade admits that every religious phenomenon is shaped by the particular culture and history that produced it:

When the Son of God incarnated and became the Christ, he had to speak Aramaic;

he could only conduct himself as a Hebrew of his times [...] His

religious message, however universal it might be, was conditioned by the

past and present history of the Hebrew people. If the Son of God had

been born in India, his spoken language would have had to conform itself

to the structure of the Indian languages.[153]

However, Eliade argues against those he calls "

historicist or

existentialist philosophers" who do not recognize "man in general" behind particular men produced by particular situations

[153] (Eliade cites

Immanuel Kant as the likely forerunner of this kind of "historicism").

[154] He adds that human consciousness transcends (is not reducible to) its historical and cultural conditioning,

[155] and even suggests the possibility of a "transconscious".

[156]

By this, Eliade does not necessarily mean anything supernatural or

mystical: within the "transconscious", he places religious motifs,

symbols, images, and nostalgias that are supposedly universal and whose

causes therefore cannot be reduced to historical and cultural

conditioning.

[157]

Platonism and "primitive ontology"

According

to Eliade, traditional man feels that things "acquire their reality,

their identity, only to the extent of their participation in a

transcendent reality".

[86]

To traditional man, the profane world is "meaningless", and a thing

rises out of the profane world only by conforming to an ideal, mythical

model.

[158]

Eliade describes this view of reality as a fundamental part of "primitive

ontology" (the study of "existence" or "reality").

[158] Here he sees a similarity with the philosophy of

Plato, who believed that physical phenomena are pale and transient imitations of eternal models or "Forms" (

see Theory of forms). He argued:

Plato could be regarded as the outstanding philosopher of 'primitive

mentality,' that is, as the thinker who succeeded in giving philosophic

currency and validity to the modes of life and behavior of archaic

humanity.[158]

Eliade thinks the

Platonic Theory of forms is "primitive ontology" persisting in

Greek philosophy. He claims that Platonism is the "most fully elaborated" version of this primitive ontology.

[159]

In

The Structure of Religious Knowing: Encountering the Sacred in Eliade and Lonergan,

John Daniel Dadosky

argues that, by making this statement, Eliade was acknowledging

"indebtedness to Greek philosophy in general, and to Plato's theory of

forms specifically, for his own theory of archetypes and repetition".

[160] However, Dadosky also states that "one should be cautious when trying to assess Eliade's indebtedness to Plato".

[161] Dadosky quotes

Robert Segal,

a professor of religion, who draws a distinction between Platonism and

Eliade's "primitive ontology": for Eliade, the ideal models are patterns

that a person or object may or may not imitate; for Plato, there is a

Form for everything, and everything imitates a Form by the very fact

that it exists.

[162]

Existentialism and secularism

Behind

the diverse cultural forms of different religions, Eliade proposes a

universal: traditional man, he claims, "always believes that there is an

absolute reality,

the sacred, which transcends this world but manifests itself in this world, thereby sanctifying it and making it real".

[163]

Furthermore, traditional man's behavior gains purpose and meaning

through the Sacred: "By imitating divine behavior, man puts and keeps

himself close to the gods—that is, in the real and the significant."

[164]

According to Eliade, "modern nonreligious man assumes a new existential situation".

[163]

For traditional man, historical events gain significance by imitating

sacred, transcendent events. In contrast, nonreligious man lacks sacred

models for how history or human behavior should be, so he must decide on

his own how history should proceed—he "regards himself solely as the

subject and agent of history, and refuses all appeal to transcendence".

[165]

From the standpoint of religious thought, the world has an objective

purpose established by mythical events, to which man should conform

himself: "Myth teaches [religious man] the primordial 'stories' that

have constituted him existentially."

[166] From the standpoint of

secular

thought, any purpose must be invented and imposed on the world by man.

Because of this new "existential situation", Eliade argues, the Sacred

becomes the primary obstacle to nonreligious man's "freedom". In viewing

himself as the proper maker of history, nonreligious man resists all

notions of an externally (for instance, divinely) imposed order or model

he must obey: modern man "

makes himself, and he only makes

himself completely in proportion as he desacralizes himself and the

world. [...] He will not truly be free until he has killed the last

god".

[165]

Religious survivals in the secular world

Eliade

says that secular man cannot escape his bondage to religious thought.

By its very nature, secularism depends on religion for its sense of

identity: by resisting sacred models, by insisting that man make history

on his own, secular man identifies himself only through opposition to

religious thought: "He [secular man] recognizes himself in proportion as

he 'frees' and 'purifies' himself from the '

superstitions' of his ancestors."

[167] Furthermore, modern man "still retains a large stock of camouflaged myths and degenerated rituals".

[168]

For example, modern social events still have similarities to

traditional initiation rituals, and modern novels feature mythical

motifs and themes.

[169]

Finally, secular man still participates in something like the eternal

return: by reading modern literature, "modern man succeeds in obtaining

an 'escape from time' comparable to the 'emergence from time' effected

by myths".

[170]

Eliade sees traces of religious thought even in secular academia. He

thinks modern scientists are motivated by the religious desire to return

to the sacred time of origins:

One could say that the anxious search for the origins of Life and

Mind; the fascination in the 'mysteries of Nature'; the urge to

penetrate and decipher the inner structure of Matter—all these longings

and drives denote a sort of nostalgia for the primordial, for the

original universal matrix. Matter, Substance, represents the absolute origin, the beginning of all things.[171]

Eliade believes the rise of materialism in the 19th century forced

the religious nostalgia for "origins" to express itself in science. He

mentions his own field of History of Religions as one of the fields that

was obsessed with origins during the 19th century:

The new discipline of History of Religions developed rapidly in this

cultural context. And, of course, it followed a like pattern: the positivistic approach to the facts and the search for origins, for the very beginning of religion.

All Western historiography was during that time obsessed with the quest of origins.

[...] This search for the origins of human institutions and cultural

creations prolongs and completes the naturalist's quest for the origin

of species, the biologist's dream of grasping the origin of life, the

geologist's and the astronomer's endeavor to understand the origin of

the Earth and the Universe. From a psychological point of view, one can

decipher here the same nostalgia for the 'primordial' and the

'original'.[172]

In some of his writings, Eliade describes modern political ideologies as secularized mythology. According to Eliade,

Marxism "takes up and carries on one of the great

eschatological

myths of the Middle Eastern and Mediterranean world, namely: the

redemptive part to be played by the Just (the 'elect', the 'anointed',

the 'innocent', the 'missioners', in our own days the

proletariat), whose sufferings are invoked to change the ontological status of the world."

[173] Eliade sees the widespread myth of the

Golden Age, "which, according to a number of traditions, lies at the beginning and the end of History", as the "precedent" for

Karl Marx's vision of a

classless society.

[174] Finally, he sees Marx's belief in the final triumph of the good (the proletariat) over the evil (the

bourgeoisie) as "a truly messianic Judaeo-Christian ideology".

[174]

Despite Marx's hostility toward religion, Eliade implies, his ideology

works within a conceptual framework inherited from religious mythology.

Likewise, Eliade notes that Nazism involved a

pseudo-pagan mysticism based on

ancient Germanic religion.

He suggests that the differences between the Nazis' pseudo-Germanic

mythology and Marx's pseudo-Judaeo-Christian mythology explain their

differing success:

In comparison with the vigorous optimism of the communist myth, the

mythology propagated by the national socialists seems particularly

inept; and this is not only because of the limitations of the racial

myth (how could one imagine that the rest of Europe would voluntarily

accept submission to the master-race?), but above all because of the

fundamental pessimism of the Germanic mythology. [...] For the eschaton

prophesied and expected by the ancient Germans was the ragnarok--that is, a catastrophic end of the world.[174]

Modern man and the "Terror of history"

According

to Eliade, modern man displays "traces" of "mythological behavior"

because he intensely needs sacred time and the eternal return.

[175]

Despite modern man's claims to be nonreligious, he ultimately cannot

find value in the linear progression of historical events; even modern

man feels the "Terror of history": "Here too [...] there is always the

struggle against Time, the hope to be freed from the weight of 'dead

Time,' of the Time that crushes and kills."

[176]

According to Eliade, this "terror of history" becomes especially

acute when violent and threatening historical events confront modern

man—the mere fact that a terrible event has happened, that it is part of

history, is of little comfort to those who suffer from it. Eliade asks

rhetorically how modern man can "tolerate the catastrophes and horrors

of history—from collective deportations and massacres to

atomic bombings—if beyond them he can glimpse no sign, no transhistorical meaning".

[177]

Eliade indicates that, if repetitions of mythical events provided

sacred value and meaning for history in the eyes of ancient man, modern

man has denied the Sacred and must therefore invent value and purpose on

his own. Without the Sacred to confer an absolute, objective value upon

historical events, modern man is left with "a

relativistic or

nihilistic view of history" and a resulting "spiritual aridity".

[178] In chapter 4 ("The Terror of History") of

The Myth of the Eternal Return and chapter 9 ("Religious Symbolism and the Modern Man's Anxiety") of