begin quote from:

The Robot Will See You Now

harley lukov didn’t need a miracle. He just needed the right diagnosis. Lukov, a 62-year-old from central New Jersey, had stopped smoking 10 years earlier—fulfilling a promise he’d made to his daughter, after she gave birth to his first grandchild. But decades of cigarettes had taken their toll. Lukov had adenocarcinoma, a common cancer of the lung, and it had spread to his liver. The oncologist ordered a biopsy, testing a surgically removed sample of the tumor to search for particular “driver” mutations. A driver mutation is a specific genetic defect that causes cells to reproduce uncontrollably, interfering with bodily functions and devouring organs. Think of an on/off switch stuck in the “on” direction. With lung cancer, doctors typically test for mutations called EGFR and ALK, in part because those two respond well to specially targeted treatments. But the tests are a long shot: although EGFR and ALK are the two driver mutations doctors typically see with lung cancer, even they are relatively uncommon. When Lukov’s cancer tested negative for both, the oncologist prepared to start a standard chemotherapy regimen—even though it meant the side effects would be worse and the prospects of success slimmer than might be expected using a targeted agent.

This article appears in the March 2013 issue.

Check out the full table of contents and find your next story to read.

But Lukov’s true medical condition wasn’t quite so grim. The tumor did have a driver—a third mutation few oncologists test for in this type of case. It’s called KRAS. Researchers have known about KRAS for a long time, but only recently have they realized that it can be the driver mutation in metastatic lung cancer—and that, in those cases, it responds to the same drugs that turn it off in other tumors. A doctor familiar with both Lukov’s specific medical history and the very latest research might know to make the connection—to add one more biomarker test, for KRAS, and then to find a clinical trial testing the efficacy of KRAS treatments on lung cancer. But the national treatment guidelines for lung cancer don’t recommend such action, and few physicians, however conscientious, would think to do these things.

Did Lukov ultimately get the right treatment? Did his oncologist make the connection between KRAS and his condition, and order the test? He might have, if Lukov were a real patient and the oncologist were a real doctor. They’re not. They are fictional composites developed by researchers at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, in order to help train—and demonstrate the skills of—IBM’s Watson supercomputer. Yes, this is the same Watson that famously went on Jeopardy and beat two previous human champions. But IBM didn’t build Watson to win game shows. The company is developing Watson to help professionals with complex decision making, like the kind that occurs in oncologists’ offices—and to point out clinical nuances that health professionals might miss on their own.

Information technology that helps doctors and patients make decisions has been around for a long time. Crude online tools like WebMD get millions of visitors a day. But Watson is a different beast. According to IBM, it can digest information and make recommendations much more quickly, and more intelligently, than perhaps any machine before it—processing up to 60 million pages of text per second, even when that text is in the form of plain old prose, or what scientists call “natural language.”

That’s no small thing, because something like 80 percent of all information is “unstructured.” In medicine, it consists of physician notes dictated into medical records, long-winded sentences published in academic journals, and raw numbers stored online by public-health departments. At least in theory, Watson can make sense of it all. It can sit in on patient examinations, silently listening. And over time, it can learn. Just as Watson got better at Jeopardy the longer it played, so it gets better at figuring out medical problems and ways of treating them the more it interacts with real cases. Watson even has the ability to convey doubt. When it makes diagnoses and recommends treatments, it usually issues a series of possibilities, each with its own level of confidence attached.

Medicine has never before had a tool quite like this. And at an unofficial coming-out party in Las Vegas last year, during the annual meeting of the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society, more than 1,000 professionals packed a large hotel conference hall, and an overflow room nearby, to hear a presentation by Marty Kohn, an emergency-room physician and a clinical leader of the IBM team training Watson for health care. Standing before a video screen that dwarfed his large frame, Kohn described in his husky voice how Watson could be a game changer—not just in highly specialized fields like oncology but also in primary care, given that all doctors can make mistakes that lead to costly, sometimes dangerous, treatment errors.

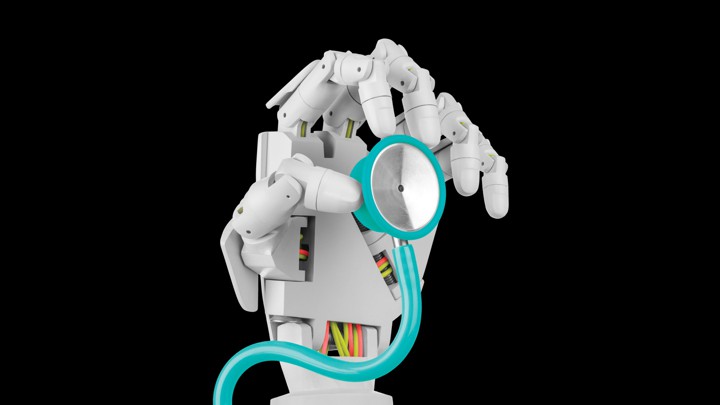

Drawing on his own clinical experience and on academic studies, Kohn explained that about one-third of these errors appear to be products of misdiagnosis, one cause of which is “anchoring bias”: human beings’ tendency to rely too heavily on a single piece of information. This happens all the time in doctors’ offices, clinics, and emergency rooms. A physician hears about two or three symptoms, seizes on a diagnosis consistent with those, and subconsciously discounts evidence that points to something else. Or a physician hits upon the right diagnosis, but fails to realize that it’s incomplete, and ends up treating just one condition when the patient is, in fact, suffering from several. Tools like Watson are less prone to those failings. As such, Kohn believes, they may eventually become as ubiquitous in doctors’ offices as the stethoscope.

“Watson fills in for some human limitations,” Kohn told me in an interview. “Studies show that humans are good at taking a relatively limited list of possibilities and using that list, but are far less adept at using huge volumes of information. That’s where Watson shines: taking a huge list of information and winnowing it down.”

Watson has gotten some media hype already, including articles in Wired and Fast Company. Still, you probably shouldn’t expect to see it the next time you visit your doctor’s office. Before the computer can make real-life clinical recommendations, it must learn to understand and analyze medical information, just as it once learned to ask the right questions on Jeopardy. That’s where Memorial Sloan-Kettering comes in. The famed cancer institute has signed up to be Watson’s tutor, feeding it clinical information extracted from real cases and then teaching it how to make sense of the data. “The process of pulling out two key facts from a Jeopardy clue is totally different from pulling out all the relevant information, and its relationships, from a medical case,” says Ari Caroline, Sloan-Kettering’s director of quantitative analysis and strategic initiatives. “Sometimes there is conflicting information. People phrase things different ways.” But Caroline, who approached IBM about the research collaboration, nonetheless predicts that Watson will prove “very valuable”—particularly in a field like cancer treatment, in which the explosion of knowledge is already overwhelming. “If you’re looking down the road, there are going to be many more clinical options, many more subtleties around biomarkers … There will be nuances not just in interpreting the case but also in treating the case,” Caroline says. “You’re going to need a tool like Watson because the complexity and scale of information will be such that a typical decision tool couldn’t possibly handle it all.”

The Cleveland Clinic is also helping to develop Watson, first as a tool for training young physicians and then, possibly, as a tool at the bedside itself. James Young, the executive dean of the Cleveland Clinic medical school, told The Plain Dealer, “If we can get Watson to give us information in the health-care arena like we’ve seen with more-general sorts of knowledge information, I think it’s going to be an extraordinary tool for clinicians and a huge advancement.” And WellPoint, the insurance company, has already begun testing Watson as a support tool for nurses who make treatment-approval decisions.

Whether these experiments show real, quantifiable improvements in the quality or efficiency of care remains to be seen. If Watson tells physicians only what they already know, or if they end up ordering many more tests for no good reason, Watson could turn out to be more hindrance than help. But plenty of serious people in the fields of medicine, engineering, and business think Watson will work (IBM says that it could be widely available within a few years). And many of these same people believe that this is only the beginning—that whether or not Watson itself succeeds, it is emblematic of a quantum shift in health care that’s just now getting under way.

when we think of breakthroughs in medicine, we conjure up images of new drugs or new surgeries. When we think of changes to the health-care system, byzantine legislation comes to mind. But according to a growing number of observers, the next big thing to hit medical care will be new ways of accumulating, processing, and applying data—revolutionizing medical care the same way Billy Beane and his minions turned baseball into “moneyball.” Many of the people who think this way—entrepreneurs from Silicon Valley, young researchers from prestigious health systems and universities, and salespeople of every possible variety—spoke at the conference in Las Vegas, proselytizing to the tens of thousands of physicians and administrators in attendance. They say a range of innovations, from new software to new devices, will transform the way all of us interact with the health-care system—making it easier for us to stay healthy and, when we do get sick, making it easier for medical professionals to treat us. They also imagine the transformation reverberating through the rest of the economy, in ways that may be even more revolutionary.

Health care already represents one-sixth of America’s gross domestic product. And that share is growing, placing an ever-larger strain on paychecks, corporate profits, and government resources. Figuring out how to manage this cost growth—how to meet the aging population’s medical needs without bankrupting the country—has become the central economic-policy challenge of our time. These technology enthusiasts think they can succeed where generations of politicians, business leaders, and medical professionals have failed.

Specifically, they imagine the application of data as a “disruptive” force, upending health care in the same way it has upended almost every other part of the economy—changing not just how medicine is practiced but who is practicing it. In Silicon Valley and other centers of innovation, investors and engineers talk casually about machines’ taking the place of doctors, serving as diagnosticians and even surgeons—doing the same work, with better results, for a lot less money. The idea, they say, is no more fanciful than the notion of self-driving cars, experimental versions of which are already cruising California streets. “A world mostly without doctors (at least average ones) is not only reasonable, but also more likely than not,” wrote Vinod Khosla, a venture capitalist and co-founder of Sun Microsystems, in a 2012 TechCrunch article titled “Do We Need Doctors or Algorithms?” He even put a number on his prediction: someday, he said, computers and robots would replace four out of five physicians in the United States.

Statements like that provoke skepticism, derision, and anger—and not only from hidebound doctors who curse every time they have to turn on a computer. Bijan Salehizadeh, a trained physician and a venture capitalist, responded to reports of Khosla’s premonition and similar predictions with a tweet: “Getting nauseated reading the anti-doctor rantings of the silicon valley tech crowd.” Physicians, after all, do more than process data. They attend at patients’ bedsides and counsel families. They grasp nuance and learn to master uncertainty. For their part, the innovators at IBM make a point of presenting Watson as a tool that can help health-care professionals, rather than replace them. Think Dr. McCoy using his tricorder to diagnose a phaser injury on Star Trek, not the droid fitting Luke Skywalker with a robotic hand in Star Wars. To most experts, that’s a more realistic picture of what medicine will look like, at least for the foreseeable future.

But even if data technology does nothing more than arm health-care professionals with tablet computers that help them make decisions, the effect could still be profound. Harvey Fineberg, the former dean of the Harvard School of Public Health and now the president of the Institute of Medicine, wrote of IT’s rising promise last year in The New England Journal of Medicine, describing a health-care system that might be transformed by artificial intelligence, robotics, bioinformatics, and other advances. Tools like Watson could enhance the abilities of professionals at every level, from highly specialized surgeons to medical assistants. As a result, physicians wouldn’t need to do as much, and each class of professionals beneath them could take on greater responsibility—creating a financially sustainable way to meet the aging population’s growing need for more health care.

As an incidental benefit, job opportunities for people with no graduate degree, and in some cases no four-year-college degree, would grow substantially. For the past few decades, as IT has disrupted other industries, from manufacturing to banking, millions of well-paying middle-class jobs—those easily routinized—have vanished. In health care, this disruption could have the opposite effect. It wouldn’t be merely a win-win, but a win-win-win. It all sounds far too good to be true—except that a growing number of engineers, investors, and physicians insist that it isn’t.

one of these enthusiasts is Daniel Kraft, age 44, whose career trajectory tracks the way medicine itself is evolving. Kraft is a physician with a traditional educational pedigree: an undergraduate degree from Brown and a medical degree from Stanford. He trained in pediatrics and internal medicine at Harvard-affiliated hospitals in Boston. Then he returned to the West Coast, to Stanford University Hospital, to complete fellowships in hematology and oncology.

But Kraft always had a flair for entrepreneurship and a taste for technology: While in medical school, he started his own online bookstore, selling texts to his classmates at a discount. (He later sold the business, for considerable profit.) At Stanford, Kraft says he used his knowledge of social media to develop a better method for communication among doctors, allowing them to exchange pertinent information while making rounds, for instance, rather than simply texting phone numbers for callbacks. “Here we are at Stanford, heart of Silicon Valley, and all we had were basic SMS text pagers—they could only do phone numbers,” Kraft recalls. “So I hacked into a Yahoo Groups thing, so we could send actual text messages through servers. Then it spread to the rest of the hospital.”

Thus began Kraft’s second, parallel career as an inventor, an entrepreneur, and a professional visionary. He audited classes in bio-design and business, hanging out with computer nerds as much as doctors. Today he holds several patents, including one for the MarrowMiner, a device that allows bone marrow to be harvested faster and less painfully. (Kraft is the chief medical officer for a company that plans to develop it commercially.) Kraft is also the chairman of the medical track at Singularity University, a think tank and educational institution in Silicon Valley. Initially, Kraft’s primary role at Singularity was to offer a few hours of instruction on medicine. But Kraft says he quickly realized that “a lot of people, in gaming, IT, Big Data, devices, virtual reality, psychology—they were all converging on health care, and interested in applying their skills to health care.” That led Singularity to establish FutureMed, an annual conference on medical innovation that brings together financiers, physicians, and engineers from around the world. Kraft is the director.

Exponential improvements in the ability of computers to process more and more data, faster and faster, are part of what has drawn this diverse crew to medicine—a field of such complexity that large parts of it have, until recently, stood outside the reach of advanced information technology. But just as significant, Kraft and his fellow travelers say, is the explosion of data available for these tools to manipulate. The Human Genome Project completed its detailed schematic of human DNA in 2003, and for the past several years, companies have provided personal genetic mapping to people with the means to pay for it. Now the price, once prohibitive, is within reach for most people and insurance plans. Researchers have only just begun figuring out how genes translate into most aspects of health, but they already know a great deal about how certain genetic sequences predispose people to conditions like heart disease and breast cancer. Many experts think we will soon enter an era of “personalized” medicine, in which physicians tailor treatments—not just for cancer, but also for conditions like diabetes and heart disease—to an individual patient’s genetic idiosyncrasies.

A potentially larger—and, in the short run, more consequential—data explosion involves the collection, transmission, and screening of relatively simple medical data on a much more frequent basis, enabling clinicians to make smarter, quicker decisions about their patients. The catalyst is a device most patients already have: the smartphone. Companies are developing, and in some cases already selling, sensors that attach to phones, to collect all sorts of biological data. The companies Withings and iHealth, for example, already offer blood-pressure cuffs that connect to an iPhone; the phone can then send the data to health-care professionals via e‑mail, or in some cases, automatically enter them into online medical records. The Withings device sells for $129; iHealth’s for $99. Other firms sell devices that diabetics can use to measure glucose levels. In the U.K., a consortium has been developing a smartphone app paired with a device that will allow users to test themselves for sexually transmitted diseases. (The test will apparently involve urinating onto a chip attached to the phone.)

AliveCor, a San Francisco–based firm, has developed an app and a thin, unobtrusive smartphone attachment that can take electrocardiogram readings. The FDA approved it for use in the U.S. in December. While the device was still in its trial phase, Eric Topol, the chief academic officer at Scripps Health in San Diego and a well-known technology enthusiast, used a prototype of the device to diagnose an incipient heart attack in a passenger on a transcontinental flight from Washington, D.C., to San Diego. The plane made an emergency landing near Cincinnati and the man survived.

Ari Caroline and his colleagues at Sloan-Kettering are leading Watson's training in cancer care. "You're going to need a tool like Watson," he says, given the rapidly increasing complexity of the field. (Kareem Black)

As sensors shrink and improve, they will increasingly allow health to be tracked constantly and discreetly—helping people to get over illnesses faster and more reliably—and in the best of cases, to avoid getting sick in the first place. One group of researchers, based at Emory University and Georgia Tech, developed a prototype for one such device called StealthVest, which—as the name implies—embeds sensors in a vest that people could wear under their regular clothing. The group designed the vest for teenagers with chronic disease (asthma, diabetes, even sickle-cell anemia) because, by their nature, teenagers are less likely to comply with physician instructions about taking readings or medications. But the same technology can work for everyone. For instance, as Sloan-Kettering’s Ari Caroline notes, right now it’s hard for oncologists to get the detailed patient feedback they need in order to serve their patients best. “Think about prostate surgery,” he says. “You really want to check patients’ urinary and sexual function on a regular basis, and you don’t get that when they come in once every three or four months to the clinic—they’ll just say generally ‘good’ or ‘bad.’ The data will only get collected when people are inputting it on a regular basis and it captures their daily lives.”

As more and more data are captured, and as computers become better and faster at processing them autonomously, the possibilities keep expanding. One medical-data start-up getting some buzz is a company called Predictive Medical Technologies, based in San Francisco. It is developing a program that sucks in all the data generated in a hospital’s intensive-care unit, plugs the information into an algorithm, and then identifies which patients are likely to experience a heart attack or other forms of distress—providing up to 24 hours of warning. A trial is under way at the University of Utah’s hospital in Salt Lake City. The eventual goal is to expand the program’s capabilities, so that it can monitor conditions throughout the hospital. “You don’t just want more data,” Kraft says. “You want actual information in a form you can use. You need to be able to make sense of this stuff. That’s what companies like Predictive Medical do.”

Watson "fills in for some human limitations," says IBM's Marty Kohn, a physician, who emphasizes that Watson is being developed to support doctors, not replace them. (Kareem Black)

so how would all these innovations fit together? How would the health-care system be different—and how, from a patient’s standpoint, would it feel different—from the one we have today? Imagine you’re an adult with a chronic condition like high blood pressure. Today, your contact with the health-care system would be largely episodic: You’d have regular checkups, at which a doctor or maybe a nurse-practitioner would check your blood pressure and ask about recent behavior—diet, exercise, and whatnot. Maybe you’d give an accurate account, maybe you wouldn’t. If you started experiencing pain or had some other sign of trouble, you’d make an appointment and come in—but by then, the symptom might well have subsided, making it hard to figure out what was going on.

In the future as the innovators imagine it—“Health 2.0,” as some people have started calling it—you would be in constant contact with the health-care system, although you’d hardly be aware of it. The goal would be to keep you healthy—and any time you were in danger of becoming unhealthy, to ensure you received attention right away. You might wear a bracelet that monitors your blood pressure, or a pedometer that logs movement and exercise. You could opt for a monitoring system that makes sure you take your prescribed medication, at the prescribed intervals. All of these devices would transmit information back to your provider of basic medical care, dumping data directly into an electronic medical record.

And the provider wouldn’t be one doctor, but rather a team of professionals, available at all hours and heavily armed with technology to guide and assist them as they made decisions. If, say, your blood pressure suddenly spiked, data-processing tools would warn them that you might be in trouble, and some sort of clinician—a nurse, perhaps—would reach out to you immediately, to check on your condition and arrange treatment as necessary. You could reach the team just as easily, with something as simple as a text message or an e-mail. You’d be in touch with them more frequently, most likely, but for much shorter durations—and, for the most part, with less urgency.

Sometimes, of course, office or hospital visits would be necessary, but that experience would be different, too—starting with the hassle of dealing with insurance companies. Watson has a button for submitting treatment proposals to managed-care companies, for near-instant approval, reducing the time and hassle involved in gaining payment authorization. The transformation of the clinical experience could be more profound, although you might not detect it: someone in a white coat or blue scrubs would still examine you, perform tests, prescribe treatment. But that person might have a different background than he’d have today. And as the two of you talked, your exam information would be uploaded and cross-referenced against your medical record (including the data from all those wireless monitors you’ve been toting around), your DNA, and untold pages of clinical literature.

The evolution toward a more connected system of care has already begun at some large organizations that use team models of care. One such institution is the Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, a nonprofit, multi-specialty group practice. Matt Handley, the medical director for quality and informatics, says that about two-thirds of Group Health’s patients now use some form of electronic communication, and that these methods account for about half of all “touches” between patients and the group’s doctors or nurses. “They set up their own appointments … They don’t need to call somebody and ask when I’m free,” Handley says. “They send messages to doctors; look up lab tests and radiology results; and order refills … The fascinating thing is that people of all ages are using it … I have people in their 90s who secure-message me.”

It’s a long way from Group Health to Health 2.0, and Handley is among those who are wary of the hype. Sure, the demos for products like Watson look great. They always do. But can such tools really winnow down information in a way that physicians will find useful? Can they effectively scour new medical literature—some 30,000 articles a month, by Handley’s reckoning—and make appropriate use of new evidence? Will they actually improve medicine? “While Watson could sometimes be helpful, it may actually drive up the cost of care,” Handley says, by introducing more possible diagnoses for each patient—diagnoses that clinicians will inevitably want to investigate with a bevy of expensive tests. A study in the journal Health Affairs, published in March 2012, found that physicians with instant electronic access to test results tended to order more tests—perhaps because they knew they could see and use the results quickly. It’s the same basic principle Handley has identified: if new tools allow providers to process far more information than they do now, providers might respond by trying to gather even more information.

Another reason for skepticism is the widespread lack of good electronic medical records, or EMRs, the foundation on which so many promising innovations rest. Creating EMRs has been a frustratingly slow process, spanning at least the past two decades. And even today the project is a mess: more than 400 separate vendors offer EMRs, and the government is still trying to establish a common language so that they can all “speak” to one another. “Our doctors have state-of-the-art electronic health-record systems,” says Brian Ahier, the health‑IT evangelist (yes, that is his real title) at the Mid-Columbia Medical Center, in northern Oregon, and a widely read writer on medical innovation. “But for clinical communication” outside the medical center, “they have to print it out, fax it, and then scan” what they get back.

But despite these risks and stumbling blocks, there are reasons to think the next wave of innovations might really stick. One is legislation enacted by the Obama administration. The 2009 Recovery Act—the $800 billion stimulus designed to end the economic crisis—set aside funds for the creation of a uniform standard for electronic medical records. It also made changes to Medicare, so reimbursement to doctors and hospitals now depends partly on whether they adopt EMRs and put them to “meaningful use.” The incentives seem to be working: according to a September 2012 survey by the consulting firm CapSite, nearly seven in 10 doctors now use EMRs. The trade publication InformationWeek called this tally a “tipping point.”

Under the Affordable Care Act, a k a “Obamacare,” Medicare will also begin rewarding providers who form integrated organizations, like Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, and groups that accept “bundled” payments, so that they are paid based on the number of patients in their care rather than for each service rendered. In theory, this financing scheme should encourage medical practices and hospitals to keep patients healthier over the long term, even if that means spending money up front on technology in order to reduce the frequency of patient visits or procedures. In other words, the new, digital model for health care should eventually become more economically viable.

one sign that medical care is in the midst of a massive transformation, or at least on the cusp of one, is the extraordinary rise in demand for information-technology workers within the health-care sector. All over the country, hospitals are on a hiring binge, desperate for people who can develop and install new information systems—and then manage them or train existing workers to do so. According to one government survey, online advertisements for health-IT jobs tripled from 2009 to 2010. And the growth is likely to continue. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that in this decade, the health-IT workforce will grow by 20 percent. Most experts believe that such growth still won’t be nearly enough to fill the demand. But it’s the data revolution’s ability to change jobs within health care—to alter the daily workflow of medical assistants, nurses, doctors, and care managers—that might have the most far-reaching effects not just on medicine, but also on the economy.

Economists like to say that health care suffers from a phenomenon called “Baumol’s disease,” or “the Baumol effect,” first described half a century ago by the economist William Baumol, in collaboration with a fellow economist named William Bowen. In most occupations, wages rise only when productivity improves. If factory workers get an extra dollar an hour, it’s because they can produce extra value, thanks to better training or equipment. Baumol and Bowen observed that certain labor-intensive occupations don’t operate by the same principle: job productivity doesn’t rise much, but wages go up anyway, because employers need to keep paying workers more in order to stop them from pursuing other lines of work, in other sectors where productivity is rising quickly. That forces the employers to keep raising prices, just to provide the same level of service.

Over time, industries afflicted with Baumol’s disease tend to consume a larger and larger proportion of a nation’s income, because their cost, relative to everything else, climbs ever upward. The health-care industry has a textbook case of Baumol’s disease, and so far, technology hasn’t made much of an impact. Just as it still takes five string players to play a Mozart quintet (Baumol’s famous example), so it still takes a highly trained surgeon to operate on somebody. “We do now have robots performing surgery, but the robot is under constant supervision of the surgeon during the process,” Baumol told a reporter from The New York Times two years ago. “You haven’t saved labor. You have done other good things, but it isn’t a way of cheapening the process.” Likewise, a doctor in a clinic still sees patients individually, listens to their problems, orders tests, makes diagnoses—in the classic economic sense, the process of an office visit is no more efficient than it was 10, 30, or 50 years ago.

Now technology could actually change that process, not by making the exam faster but by enabling somebody else to conduct it—or to perform the test, or carry out the procedure. The idea of robots performing surgery or more-routine medical tasks with less supervision is something many experts take seriously—in part because, in the developing world, burgeoning demand for care is already pushing medicine in this direction. As part of an experimental program in Tanzania, rural health workers, many of whom have relatively little medical training, have access to a “decision-support tool” that can help them diagnose and treat illness based on symptoms. And thanks to an initiative called the Maternal Health Reporter, similar caregivers in India can submit patient information to a central data bank, then receive regular reminders about care for pregnant women.

“In Brazil and India, machines are already starting to do primary care, because there’s no labor to do it,” says Robert Kocher, an internist, a veteran of McKinsey consulting, and a former adviser to the Obama administration. He’s now a partner at Venrock, a New York venture-capital firm that invests in emerging technologies, including health-care technology. “They may be better than doctors. Mathematically, they will follow evidence—and they’re much more likely to be right.” In the United States, Kocher believes, advanced decision-support tools could quickly find a home in so-called minute clinics—the storefront medical offices that drugstores and other companies are setting up in pharmacies and malls. There, the machines could help nonphysician clinicians take care of routine medical needs, like diagnosing strep throat—and could potentially dispense the diagnoses to patients more or less autonomously. Years from now, he says, other machines could end up doing “vascular surgery, fistulas, eye surgery, microsurgery. Machines can actually be more precise than human hands.”

Nobody (including Kocher) expects American physicians to turn the keys of their practices over to robots. And nobody would expect American patients accustomed to treatment from live human beings to tolerate such a sudden shift for much of their care, mall-based minute clinics notwithstanding. But because of a unique set of circumstances, the health-care workforce could nonetheless undergo enormous change, without threatening the people already working in it.

Between the aging of the population and the expansion of health-insurance coverage under Obamacare, many more people will seek medical attention in the coming years—whether it’s basic primary care or ongoing care for chronic conditions. But we don’t have nearly enough primary-care doctors—in practice today or in training—to provide this care. And even if we trained more, we wouldn’t have enough money to pay them. With the help of decision-support tools and robotics, health-care professionals at every level would be able to handle more-complicated and more-challenging tasks, helping to shoulder part of the load. And finding enough nurses or technicians or assistants would be a lot easier than finding enough doctors. They don’t need as many years to train, and they don’t cost as much to pay once their training is finished. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, doctors’ median annual salary is $166,400, while nurses’ is $64,690 and medical assistants’ is $28,860.

Health professionals at all levels tend to guard their turf ferociously, lobbying state officials to prevent encroachments from other providers. But the severe shortage of professionals to provide primary care means there should be plenty of work to go around. Already today, there’s a push within health-care-policy circles to more consistently allow providers to “practice at the top of their licenses”—that is, to let the people at each level of training do as much as their training could possibly allow them to do. That would enable higher-wage, more-highly-skilled professionals to focus on work that’s truly commensurate with their education. It would also reduce the cost of care. Watson and its ilk could help us take this concept further, by augmenting the capabilities of workers at every skill level. Physicians could lead large teams of mid- and low-level providers, delegating less complicated and more routine tasks. “Having nurses, with the assistance of these artificial-intelligence tools, [do more] frees physicians to perform the higher-level interventions, allowing everyone to practice at the top of their license,” Brian Ahier says.

That model actually isn’t so different from the collaborative approach that institutions like Group Health have been deploying with such success. “We focus on developing teams—teams of several doctors, physician assistants, nurse-practitioners, and/or nurses,” Matt Handley says. “Every day starts with a huddle: the team talks about the day and reviews a couple of topics and cases, figures out who is going to need what, from which provider, and so on.”

The providers with less medical training can be more technologically adept, anyway. “The doctor or clinician of course has the high analytic skills, makes the judgment calls, the diagnoses, prescribes medications,” says Catherine Dower, an associate director at UC San Francisco’s Center for the Health Professions. “But the medical assistants are frequently the ones who can actually use this new technology really well, including tele-health—they can get bio-feeds from patients sitting at home, they can tap insulin and cardiac rates. And then, as this information is fed into a central site, the medical assistant can read and make a decision on which patient should come in and be seen by the doctor, and which one needs some minor modification”—whether that means adjusting medication or scheduling a visit to discuss more-significant changes in treatment or therapy.

For the health-care system as a whole, the efficiencies from the data revolution could amount to substantial savings. One estimate, from the McKinsey Global Institute, suggested that the data revolution could yield onetime heath-care savings of up to $220 billion, followed by a slower rate of growth in health-care costs. Total health-care spending in the U.S. last year was $2.7 trillion, so that would be roughly the equivalent of reducing health-care spending by 7.5 percent up front. That’s the best reason to believe that the data revolution will make a difference, even if it never lives up to the hype of its most enthusiastic proponents. The health-care system is so massive, so full of waste, so full of failure, that even a marginal change for the better could save billions of dollars, not to mention quite a few lives.

And, in a small way, it could help us begin to fill the hole that’s developed in the middle class. David Autor, an economist at MIT, has noted that for the past generation, technological change in the U.S. has tended to favor highly skilled workers at the expense of those with mid-level skills. Routine clerical functions, for instance, have been automated, contributing to the hollowing-out of the middle class. But in the coming years, health care may prove a large and important exception to that general rule—effectively turning the rule on its head. “Look at physician-assistant positions,” Dower says. “After completing a rigorous academic program that's modeled on medical school but takes less time, PAs can provide many primary- and specialty-care services at starting salaries of about $77,000.”* If technological aids allow us to push more care down to people with less training and fewer skills, more middle-class jobs will be created along the way.

“I don’t think physicians will be seeing patients as much in the future,” says David Lee Scher, a former cardiac electrophysiologist and the president of DLS Healthcare Consulting, which advises health-care organizations and developers of digital health-care technologies. “I think they are transitioning into what I see as super-quality-control officers, overseeing physician assistants, nurses, nurse-practitioners, etc., who are really going to be the ones who see the patients.” Scher recognizes the economic logic of this transition, but he’s also deeply ambivalent about it, noting that something may be lost—because there are still some things that technology cannot do, and cannot enable humans to do. “Patients appreciate nonphysician providers because they tend to spend more time with them and get more humanistic hand-holding care. However, while I personally have dealt with some excellent mid-level providers, they generally do not manage complex diseases as well as physicians. Technology-assisted algorithms might contribute to narrowing this divide.”

Even Watson, which has generated so much positive buzz in medicine and engineering, has its doubters. “Watson would be a potent and clever companion as we made our rounds,” wrote Abraham Verghese, a Stanford physician and an author, in The New York Times. “But the complaints I hear from patients, family and friends are never about the dearth of technology but about its excesses.”

Marty Kohn, from the Watson team, understands such skepticism, and frequently warns enthusiasts not to overpromise what the machine can do. “When people say IT can be transformative, I get a little anxious,” he told me. Partly that’s because he thinks technology can’t change an industry, or a culture, if the professionals themselves aren’t committed to such a transformation—Watson won’t change medicine, in other words, if the people who practice medicine don’t want it to change. As a physician, Kohn is careful to describe Watson as a “clinical support” tool rather than a “decision making” tool—to emphasize that it’s a machine that can help health-care professionals, rather than replace them. “Some technologies are truly transforming health care, providing therapies that never existed before. I don’t view IT that way. I view IT as an enabler.”

Still, Kohn has reconciled himself to hearing people talk about Watson as if it were a person—he says he’s now used to answering the question “Who is Watson?” rather than “What is Watson?” He also likes to tell a story about a speech he gave in Canada, one that, like the Las Vegas presentation, attracted more people than the room could hold. That evening he called his wife, to tell her about the enthusiasm. “That’s really great, Marty,” he recalls her saying. “Just remember, they were there to meet Watson, not you.”

No comments:

Post a Comment