begin quote from:

Bell-shaped oxygen helmets look like ‘Star Trek’ but help coronavirus patients at Penn’s hospitals

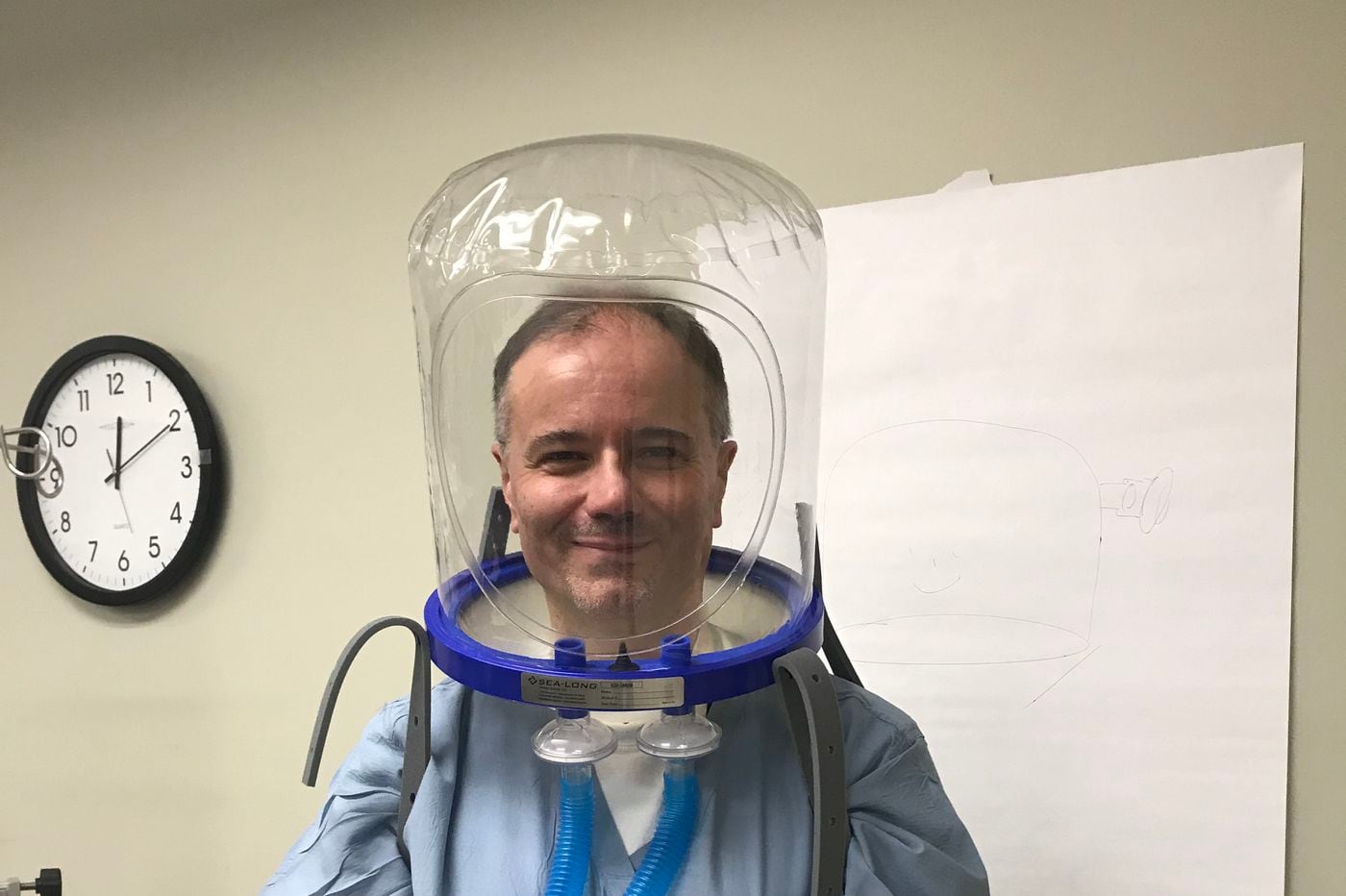

HANDOUT

Editor's Note

News about the coronavirus is changing quickly. The latest information can be found at inquirer.com/coronavirus

At the height of Italy’s pitched battle with the coronavirus, newscast footage from an overwhelmed hospital resembled a science-fiction film. Dozens of patients, in a hallway crowded with beds and wheelchairs, were wearing strange, transparent bell-shaped helmets.

“One of the obstacles to their use is that they’re weird,” said Maurizio Cereda, a proponent of the headgear and an intensive-care specialist at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania and Penn Presbyterian Medical Center. “They look like something Capt. Kirk wears in Star Trek.”

Months after the coronavirus crossed the Atlantic, those odd plastic hoods have appeared as well. And increasingly, thanks in part to the efforts of physicians like Cereda, the devices are being manufactured here and used by U.S. hospitals.

The oxygen hoods, which have been used in Italy for more than 30 years, function as mini-hyperbaric chambers, pumping pressurized oxygen into disease-compromised lungs and filtering out contaminants. They’re leak-free, cheap, and reusable. And because they’re self-contained, they protect hospital staff from the breath of patients.

COVID-19 attacks the lungs and its victims frequently develop serious breathing problems. The most seriously afflicted are intubated — a breathing tube is inserted in the windpipe — and placed on expensive ventilators. Those not as seriously ill often are administered oxygen through cumbersome face masks.

“Those masks create all sorts of problems,” said Cereda, co-director of Penn’s surgical intensive care unit. “Over the years, the design has improved, but you still can’t wear them for 24 hours. You can’t talk. You get sores on the face.”

Prompted by the coronavirus’ arrival here, Cereda and two colleagues — respiratory therapist Michael Frazer and pulmonologist Barry Fuchs — urged Penn’s health-care system to acquire several hundred. So far, Cereda said, about 75 patients have used them successfully at HUP and Presbyterian.

The transparent coverings are placed over the head and sealed at the neck, where a pair of tubes are connected. They can be extremely noisy, but their benefits are causing hospitals to look seriously at them. The helmets can reduce the number of patients requiring ventilators. While a ventilator costs from $25,000 to $50,000, a helmet typically sells for $150 to $175. And with proper cleaning, it can be used over and over again.

“I’m not saying it’s a miracle,” Cereda said. “It doesn’t replace ventilators. But you use it to keep people from needing to use a ventilator. Once you go on a ventilator, because you need sedation and a lot of other things, your chances of survival are already lower. It’s better to get off a ventilator if you can.”

According to a study published in 2016 in the Journal of the American Medical Association, patients using the headgear needed ventilation 18% of the time, while the figure was 62% for traditional oxygen masks. Penn is moving forward on its own study.

The Penn physician first encountered the devices in the early 1990s when he was a medical student in his native Italy. In the Milan hospital where he studied and worked, patients suffering from acute respiratory failure were being fitted with the helmets.

“Over there it was our go-to device for patients who were not sick enough to require a breathing tube or ventilator right away, but needed more than just an oxygen mask,” he said.

Cereda arrived in the United States in 1999, and as far back as 2006 hoped to import the devices. The Food and Drug Administration had approved them for hyperbaric medical uses, but broadening that authorization process proved complex. Cereda eventually dropped his efforts, but continued to tout them to colleagues and hospital administrators.

“I was hoping to be able to use them anywhere, on ambulances, on hospital floors,” he said. “But whenever I talked about them, they thought it sounded weird. People were like, `Oh, that’s not going to work. It’s too uncomfortable.’ But you have to know how to put it on the patient.”

As the coronavirus ravaged Italy, former colleagues were telling Cereda that they had as many 200 patients in helmets. Finally, in March, with the FDA having granted emergency approval, a supply reached Philadelphia. Within two weeks, the staffs at HUP and Presbyterian were trained and using them.

Originally intended to run through ventilators, the design has been modified and the hoods can now be connected to a hospital’s oxygen-supply system. Since the pandemic struck here, facilities in Massachusetts, New York, Illinois, Maryland, and elsewhere have utilized them.

“It’s getting some real traction,” said Cereda.

This sudden demand put a strain on the two FDA-approved manufacturers in the U.S. One, Sea-Long Health Care Systems in Waxahachie, Texas, has had to double its staff and quadruple production.

Sea-Long’s founder, Chris Austin, said that in addition to all the new U.S. business, the company has filled orders for hospitals in Europe, Canada, and Mexico, and is hoping to produce 50,000 a week.

“To say we’ve been overwhelmed would be an understatement,” said Austin.

No comments:

Post a Comment