Unmanned aerial vehicle

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"UAV" redirects here. For other uses, see UAV (disambiguation).

An MQ-9 Reaper, a hunter-killer surveillance UAV

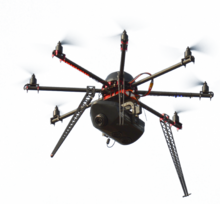

AltiGator civil drone OnyxStar Fox-C8 XT in flight.

UAV launch from an air-powered catapult

- Autonomous aircraft – currently considered unsuitable for regulation due to legal and liability issues

- Remotely piloted aircraft – subject to civil regulation under ICAO and under the relevant national aviation authority

In the past, unmanned aerial vehicles have mostly found military and special operation applications, but also are increasingly finding uses in civil applications,[3] such as policing and firefighting, and nonmilitary security work, such as inspection of power or pipelines. UAVs are often preferred for missions that are too "dull, dirty or dangerous"[4] for manned aircraft.

Contents

- 1 Definition and terminology

- 2 History

- 3 Regulation

- 4 Classification

- 5 Uses

- 5.1 Commercial aerial surveillance

- 5.2 Professional aerial surveying

- 5.3 Commercial and motion picture filmmaking

- 5.4 Journalism

- 5.5 Law enforcement

- 5.6 Search and rescue

- 5.7 Demining

- 5.8 Scientific research

- 5.9 Military Uses

- 5.10 Conservation

- 5.11 Animal rights

- 5.12 Maritime patrol

- 5.13 Surveying

- 5.14 Cargo transport

- 5.15 Farms

- 5.16 Future potential

- 6 Design and development considerations

- 7 Existing UAV systems

- 8 Historical events involving UAVs

- 9 Aircraft near-miss incidents

- 10 Accidents and incidents

- 11 UAVs in the US military

- 12 UAVs in popular culture

- 13 UAE Drones for Good Award

- 14 See also

- 15 References

- 16 External links

Definition and terminology

There are several names in use for unmanned aerial vehicles, which generally refer to the same concept. The term unmanned aircraft system (UAS) was adopted by the United States Department of Defense (DoD) and the United States Federal Aviation Administration in 2005 according to their Unmanned Aircraft System Roadmap 2005–2030.[5] The International Civil Aviation Organization and the British Civil Aviation Authority have also adopted the term. Unmanned aircraft system emphasizes the importance of other elements beyond an aircraft itself. It includes elements such as the ground control stations, data links and other related support equipment. A similar term is an unmanned-aircraft vehicle system (UAVS) remotely piloted aerial vehicle (RPAV), remotely piloted aircraft (RPA) and similar terms are also in use.Some incorrectly refer to unmanned aerial vehicles lacking autopilots as drones. Although this term is more widely used and recoginsed by the public, it has seen strong opposition from aviation professionals and government regulators familiar with correct use of language.[6]

To distinguish UAVs from missiles, a UAV is defined as a "powered, aerial vehicle that does not carry a human operator, uses aerodynamic forces to provide vehicle lift, can fly autonomously or be piloted remotely, can be expendable or recoverable, and can carry a lethal or nonlethal payload".[7] Therefore, cruise missiles are not considered UAVs because, like many other guided missiles, the vehicle itself is a weapon that is not reused, though it is also unmanned and in some cases remotely guided.

The definition of UAVs with respect to smaller smaller remote controlled model aircraft is unclear[citation needed]. According to various definitions UAVs may or may not include model aircraft[citation needed]. Some jurisdictions base this definition on size or weight, however, the US Federal Aviation Administration defines any unmanned flying craft as a UAV regardless of size. A radio-controlled aircraft becomes a drone with the addition of an autopilot AI, and ceases to be a drone when the AI is removed.[8][9]

History

Main article: History of unmanned aerial vehicles

Ryan Firebee was a series of target drones/unpiloted aerial vehicles.

In 1959, the U.S. Air Force, concerned about losing pilots over hostile territory, began planning for the use of unmanned aircraft.[13] Planning intensified after the Soviet Union shot down a U-2 in 1960. Within days, the highly classified UAV program started under the code name of "Red Wagon".[14] The August 1964 clash in the Tonkin Gulf between naval units of the U.S. and North Vietnamese Navy initiated America's highly classified UAVs (Ryan Model 147, Ryan AQM-91 Firefly, Lockheed D-21) into their first combat missions of the Vietnam War.[15] When the "Red Chinese"[16] showed photographs of downed U.S. UAVs via Wide World Photos,[17] the official U.S. response was "no comment".

The War of Attrition (1967-1970) saw the introduction of UAVs with reconnaissance cameras into combat in the Middle East.[18] In the 1973 Yom Kippur War Israel used drones as decoys to spur opposing forces into wasting expensive anti-aircraft missiles.[19]

The Israeli Tadiran Mastiff, which first flew in 1973, is seen[by whom?] as the first modern battlefield UAV, due to its data-link system, endurance-loitering, and live video-streaming.[20]

During the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Soviet-supplied surface-to-air missile batteries in Egypt and Syria caused heavy damage to Israeli fighter jets. As a result, Israel developed the first UAV with real-time surveillance.[24][25][26] The images and radar decoying provided by these UAVs helped Israel to completely neutralize the Syrian air defenses at the start of the 1982 Lebanon War, resulting in no pilots downed.[27] The first time UAVs were used as proof-of-concept of super-agility post-stall controlled flight in combat-flight simulations involved tailless, stealth technology-based, three-dimensional thrust vectoring flight control, jet-steering UAVs in Israel in 1987.[28]

With the maturing and miniaturization of applicable technologies in the 1980s and 1990s, interest in UAVs grew within the higher echelons of the U.S. military. In the 1990s, the U.S. DoD gave a contract to AAI Corporation along with Israeli company Malat. The U.S. Navy bought the AAI Pioneer UAV which AAI and Malat developed jointly. Many of these Pioneer and newly-developed U.S. UAVs saw service in the 1991 Gulf War. UAVs demonstrated the possibility of cheaper, more capable fighting machines, deployable without risk to aircrews. Initial generations primarily involved surveillance aircraft, but some carried armaments, such as the General Atomics MQ-1 Predator, which used AGM-114 Hellfire air-to-ground missiles.

As of 2012, the USAF employed 7,494 UAVs - almost one in three USAF aircraft.[29][30] The Central Intelligence Agency has also operated UAVs.[31]

In 2013, it was reported[by whom?] that at least 50 countries used UAVs. Several countries made their own: for example, Iran, Israel, and China.[32]

Regulation

Main article: Regulation of unmanned aerial vehicles

To operate a UAV for nonrecreational purposes in the United States, according to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), users must obtain a Certificate of Authorization.[33]

The use of UAVs for law-enforcement purposes is also regulated at a

state level. For commercial use in the United States, the FAA mandates

that operators must first petition for an exemption under Section 333 to

be approved for commercial use cases. [34]The Irish Aviation Authority policy is that unmanned aerial systems may not be flown without the operator receiving a specific permission from the IAA.[35]

In April 2014, the South African Civil Aviation Authority announced that it would clamp down on the illegal flying of UAVs in South African airspace.[36]

In Oct 2015, the US Department of Transportation and FAA indicated a task force would be formed to determine the requirements for registering commercial drones.[37]

Classification

| This section does not cite any references (sources). (February 2013) |

Although most UAVs are fixed-wing aircraft, rotorcraft designs (i.e., RUAVs) such as this MQ-8B Fire Scout are also used.

- Target and decoy – providing ground and aerial gunnery a target that simulates an enemy aircraft or missile

- Reconnaissance – providing battlefield intelligence

- Combat – providing attack capability for high-risk missions (see Unmanned combat air vehicle)

- Logistics – UAVs specifically designed for cargo and logistics operation

- Research and development – used to further develop UAV technologies to be integrated into field-deployed UAV aircraft

- Civil and commercial UAVs – specifically designed for civil and commercial applications

Schiebel S-100 fitted with a Lightweight Multirole Missile

- Hand-held 2,000 ft (600 m) altitude, about 2 km range

- Close 5,000 ft (1,500 m) altitude, up to 10 km range

- NATO type 10,000 ft (3,000 m) altitude, up to 50 km range

- Tactical 18,000 ft (5,500 m) altitude, about 160 km range

- MALE (medium altitude, long endurance) up to 30,000 ft (9,000 m) and range over 200 km

- HALE (high altitude, long endurance) over 30,000 ft (9,100 m) and indefinite range

- HYPERSONIC high-speed, supersonic (Mach 1–5) or hypersonic (Mach 5+) 50,000 ft (15,200 m) or suborbital altitude, range over 200 km

- ORBITAL low earth orbit (Mach 25+)

- CIS Lunar Earth-Moon transfer

- CACGS Computer Assisted Carrier Guidance System for UAVs

U.S. UAV demonstrators in 2005

Uses

In 2013, the DHL parcel service tested a "microdrones md4-1000" for delivery of medicine.

Interspect UAS B 3.1 octocopter for commercial aerial cartographic purposes and 3D mapping

Civil Drone FOX-C8-HD AltiGator

IAI Heron, an unmanned aerial vehicle developed by the Malat (UAV) division of Israel Aerospace Industries

A Hydra Technologies Ehécatl taking-off for a surveillance mission

UAVs have been used by military forces, civilian government agencies, businesses, and private individuals. In the United States, for example, government agencies use UAVs such as the RQ-9 Reaper to patrol the nation's borders, scout property, and locate fugitives.[51] One of the first authorized for domestic use was the ShadowHawk UAV in service in Montgomery County, Texas, and is being used by their SWAT and emergency management offices.[52]

Private citizens and media organizations use UAVs for surveillance, recreation, news-gathering, or personal land assessment. Occupy Wall Street journalist Tim Pool uses what he calls an "occucopter" for live feed coverage of Occupy movement events.[53] The "occucopter" is an inexpensive radio-controlled quadcopter with cameras attached and controllable by Android devices or iOS. In February 2012, an animal rights group used a MikroKopter hexacopter to film hunters shooting pigeons in South Carolina. The hunters then shot the UAV down.[54] UAVs also have been shown to have many other civilian uses, such as in agriculture, movies, and the construction industry.[55] In 2014, a drone was used in search and rescue operations to successfully located an elderly gentleman with dementia who went missing for 3 days.[56] In March 2015, the SXSW music festival in Austin, Texas banned drones, citing Wi-Fi bandwidth congestion and safety concerns.[57][58]

Commercial aerial surveillance

Aerial surveillance of large areas is made possible with low-cost UAV systems. Surveillance applications include livestock monitoring, wildfire mapping, pipeline security, home security, road patrol, and antipiracy. The trend for the use of UAV technology in commercial aerial surveillance is expanding rapidly with increased development of automated object detection approaches.[59]Professional aerial surveying

UAS technologies are used worldwide as aerial photogrammetry and LiDAR platforms.Commercial and motion picture filmmaking

In the United States, FAA regulations generally permit hobbyist drone use when they are flown below 400 feet, and within the UAV operator’s line of sight. For commercial drone camerawork inside the United States, industry sources state that usage is largely at the de facto consent – or benign neglect – of local law enforcement. Use of UAVs for filmmaking is generally easier on large private lots or in rural and exurban areas with fewer space concerns. In certain localities such as Los Angeles and New York, authorities have actively interceded to shut down drone filmmaking efforts due to concerns driven by safety or terrorism.[60][61][62]In June 2014, the FAA said it had received a petition from the Motion Picture Association of America seeking approval for the use of drones in video and filmmaking. Seven companies behind the petition argued that low-cost drones could be used for shots that would otherwise require a helicopter or a manned aircraft, which would reduce costs.[citation needed] Drones are already used by movie makers and media in other parts of the world.

Drones were used in the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi for filming skiing and snowboarding events. Some advantages of using unmanned aerial vehicles in sports are that they allow video to get closer to the athletes, and they are more flexible than cable-suspended camera systems.[63]

In the United States, Falkor Systems has targeted extreme sports photography and video for drone use, focusing on skiing and base-jumping activities.[64]

Journalism

Some journalists in the United States are interested in using drones for newsgathering. The College of Journalism and Mass Communications at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln has established the Drone Journalism Lab.[65] The University of Missouri also has created the Missouri Drone Journalism Program.[66] The Professional Society of Drone Journalists was established in 2011 and describes itself as "the first international organization dedicated to establishing the ethical, educational, and technological framework for the emerging field of drone journalism."[67] Drones have been especially useful in covering disasters such as typhoons.[68] A coalition of 11 news organizations is working with the Mid-Atlantic Aviation Partnership at Virginia Tech on how reporters could use unmanned aircraft to gather news.[69]Law enforcement

Main article: Use of UAVs in law enforcement

Many police departments in India have procured drones for law and order and aerial surveillance.[70][71][72][73]UAVs have been used for domestic police work in Canada and the United States;[60][61] a dozen US police forces had applied for UAV permits by March 2013.[32] In 2013, the Seattle Police Department’s plan to deploy UAVs was scrapped after protests.[74] UAVs have been used by U.S. Customs and Border Protection since 2005.[75] with plans to use armed drones.[76] The FBI stated in 2013 that they own and use UAVs for the purposes of "surveillance".[77]

In 2014, it was reported that five English police forces had obtained or operated unmanned aerial vehicles for observation.[78] Merseyside Police caught a car thief with a UAV in 2010, but the UAV was later lost during a training exercise[79] and the police stated the UAV would not be replaced due to operational limitations and the cost of staff training.[79]

In August 2013, the Italian defence company Selex ES provided an unarmed surveillance drone to be deployed in the Democratic Republic of Congo to monitor movements of armed groups in the region and to protect the civilian population more effectively.[80]

Search and rescue

Aeryon Scout in flight

UAVs have been tested as airborne lifeguards, locating distressed swimmers using thermal cameras and dropping life preservers to swimmers.[84][85]

Demining

The Space Assets for Demining Assistance program from the European Space Agency aims to improve the socioeconomic impact of land release activities in mine action.[86] It is developing and has tested UAV technology for demining in Bosnia-Herzegovina.[87] [88]Scientific research

See also: Research balloon

Unmanned aircraft are especially useful in penetrating areas that may be too dangerous for manned aircraft. The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration began using the Aerosonde unmanned aircraft system in 2006 as a hurricane hunter. The 35-pound system can fly into a hurricane and communicate near-real-time data directly to the National Hurricane Center.

Beyond the standard barometric pressure and temperature data typically

culled from manned hurricane hunters, the Aerosonde system provides

measurements from closer to the water’s surface than previously

captured. NASA later began using the Northrop Grumman RQ-4 Global Hawk for extended hurricane measurements.Military Uses

Reconnaissance

See also: Battlefield UAV and reconnaissance aircraft

The Tu-141 "Swift" reusable Soviet operational and tactical reconnaissance drone is intended for reconnaissance to a depth of several hundred kilometers from the front line at supersonic speeds.[89] The Tu-123

"Hawk" is a supersonic long-range reconnaissance drone (UAV) intended

for conducting photographic and signals intelligence to a distance of

3200 km; it was produced since 1964.[90] The La-17P (UAV) is a reconnaissance UAV produced since 1963.[91] Since 1945, the Soviet Union also produced "doodlebug".[92] There are 43 known Soviet UAV models.[93]In 2013, the U.S. Navy launched a UAV from a submerged submarine, the first step to “providing mission intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities to the U.S. Navy’s submarine force.”[94]

Armed attacks

Predator launching a Hellfire missile

MQ-1 Predator UAVs armed with Hellfire missiles have been used by the U.S. as platforms for hitting ground targets. Armed Predators were first used in late 2001 from bases in Pakistan and Uzbekistan, mostly aimed at assassinating high-profile individuals (terrorist leaders, etc.) inside Afghanistan. Since then, many cases of such attacks have been reported taking place in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia.[96] The advantage of using an unmanned vehicle rather than a manned aircraft in such cases is to avoid a diplomatic embarrassment should the aircraft be shot down and the pilots captured, since the bombings take place in countries deemed friendly and without the official permission of those countries.[97][98][99][100]

The “unmanned” aspect of UAVs has raised moral concerns. Some believe that the asymmetry of fighting humans with machines that are controlled from a safe distance lacks integrity and honor that was once valued during warfare. Others feel that if such technology is available, then a moral duty exists to employ it to save as many lives as possible.[101]

Defense against UAVs

The United States armed forces currently have no defense against low-level drone attack, but the Joint Integrated Air and Missile Defense Organization is working to repurpose existing systems to defend American forces.[102] Two German companies are developing 40-kW lasers to damage UAVs.[103] Three British companies have jointly developed a system to track and disrupt the control mechanism for small UAVs.[104]Civilian casualties

In March 2009, The Guardian reported allegations that Israeli UAVs armed with missiles killed 48 Palestinian civilians in the Gaza Strip, including two small children in a field and a group of women and girls in an otherwise empty street.[105] In June, Human Rights Watch investigated six UAV attacks that were reported to have resulted in civilian casualties and alleged that Israeli forces either failed to take all feasible precautions to verify that the targets were combatants or failed to distinguish between combatants and civilians.[106][107][108]

In 2009, Brookings Institution reported that in the United States-led drone attacks in Pakistan, ten civilians died for every militant killed.[109][110] A former ambassador of Pakistan said that American UAV attacks were turning Pakistani opinion against the United States.[111] The website PakistanBodyCount.Org shows 1,065 civilian deaths between 2004 and 2010.[112] According to a 2010 analysis by the New America Foundation 114 UAV-based missile strikes in northwest Pakistan from 2004 killed between 830 and 1,210 individuals, around 550 to 850 of whom were militants.[113] In October 2013 the Pakistani government revealed that since 2008 there had been 317 drone strikes that killed 2,160 Islamic militants and 67 civilians - far less than previous government and independent organization calculations.[114]

Targets for military training

Main article: Target drone

Since 1997, the U.S. military has used more than 80 F-4 Phantoms converted into robotic planes for use as aerial targets for combat training of human pilots.[115] The F-4s were supplemented in September 2013 with F-16s as more realistically maneuverable targets.[115]Conservation

ShadowView Eco Ranger

In June 2012, World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) announced it will begin using UAVs in Nepal to aid conservation efforts following a successful trial of two aircraft in Chitwan National Park, with ambitions to expand to other countries, such as Tanzania and Malaysia. The global wildlife organization plans to train ten personnel to use the UAVs, with operational use beginning in the fall.[117][118] In August 2012, UAVs were used by members of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society in Namibia to document the annual seal cull.[119] In December 2013, the Falcon UAV was selected by the Namibian Govt and WWF to help combat rhino poaching.[120] The drones will be monitoring rhino populations in Etosha National Park and will use RFID sensors.[121]

In 2012, the WWFund supplied two FPV Raptor 1.6 UAVs[122] to the Nepal National Parks. These UAVs were used to monitor rhinos, tigers, and elephants and deter poachers.[123] The UAVs were equipped with time-lapse cameras and could fly for 18 miles at 650 feet.[124]

In December 2012, the Kruger National Park started using a Seeker II UAV against rhino poachers. The UAV was loaned to the South African National Parks authority by its manufacturer, Denel Dynamics of South Africa.[125][126]

Animal rights

Anti-whaling activists used an Osprey UAV (made by Kansas-based Hangar 18) in 2012 to monitor Japanese whaling ships in the Antarctic.[127]In 2012, the Ulster Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals used a quadcopter UAV to deter badger baiters in Northern Ireland.[128] In March 2013, the British League Against Cruel Sports announced they had carried out trial flights with UAVs and planned to use a fixed-wing OpenRanger and an "octocopter" to gather evidence to make private prosecutions against illegal hunting of foxes and other animals.[125] The UAVs were supplied by ShadowView. A spokesman for Privacy International said that "licencing and permission for drones is only on the basis of health and safety, without considering whether privacy rights are violated."[125] CAA rules prohibit flying a UAV within 50 m of a person or vehicle.[125][129]

In Pennsylvania, Showing Animals Respect and Kindness used drones to monitor people shooting at pigeons for sport.[130] One of their octocopter drones was shot down by hunters.[131]

In March 2013, the Times published a controversial story that UAV conservation nonprofit ShadowView, founded by former members of Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, had been working for several months with antihunting charity the League Against Cruel Sports to expose illegal fox hunting in the UK.[132] Hunt supporters have argued that using UAVs to film hunting is an invasion of privacy.[133]

In 2014, Will Potter proposed using drones to monitor conditions on factory farms. The idea is to circumvent ag-gag prohibitions by keeping the drones on public property, but equipping them with cameras sensitive enough to monitor activities on the farms.[134] Potter raised nearly $23,000 in 2 days for this project on Kickstarter.[134]

Maritime patrol

Japan is studying how to deal with the UAVs China is starting to use to enforce their claims on unmanned islands.[135]Surveying

Oil, gas, and mineral exploration and production

Camclone T21 UAV fitted with CSIRO guidance system used to inspect power lines (2009)

Disaster relief

Drones can help in disaster relief by gathering information from across an affected area to build a picture of the situation and give recommendations to direct resources.[138]T-Hawk[139] and Global Hawk[140] drones were used to gather information about the damaged Fukushima Number 1 nuclear plant and disaster-stricken areas of the Tōhoku region after the March 2011 tsunami.

Archaeology

In Peru, archaeologists use drones to speed up survey work and protect sites from squatters, builders, and miners. Small drones helped researchers produce three-dimensional models of Peruvian sites instead of the usual flat maps – and in days and weeks instead of months and years.[141]Drones have replaced expensive and clumsy small planes, kites, and helium balloons. Drones costing as little as £650 have proven useful. In 2013, drones flew over at least six Peruvian archaeological sites, including the colonial Andean town Machu Llacta 4,000 m (13,000 ft) above sea level. The drones continue to have altitude problems in the Andes, leading to plans to make a drone blimp.[141]

An archaeologist said, "You can go up three metres and photograph a room, 300 metres and photograph a site, or you can go up 3,000 metres and photograph the entire valley."[141]

In September 2014, drones weighing about 0.5 kg were used for 3D mapping of the above-ground ruins of the Greek city of Aphrodisias.[142]

Venezuela

In 2012, Cavim, the state-run arms manufacturer of Venezuela, claimed to be producing its own UAV as part of a system to survey and monitor pipelines, dams, and other rural infrastructure. The UAV had a range of 100 km, a maximum altitude of 3,000 m, could fly for 90 minutes, and measured 3 by 4 m.[143][144]Cargo transport

Main article: Delivery drone

The RQ-7 Shadow can deliver a "Quick-MEDS" canister to front-line troops.

Initial attempts at commercial use of UAVs, such as the Tacocopter company for food delivery, were blocked by FAA regulation.[145] A 2013 announcement that Amazon was planning deliveries using UAVs was met with skepticism.[146]

In 2013, in a research project of DHL, a small quantity of medicine was delivered via a UAV.[147][148]

In 2014, the prime minister of the United Arab Emirates announced that the UAE planned to launch a fleet of UAVs[149] to deliver official documents and supply emergency services at accidents.[150]

Google revealed in 2014 it had been testing UAVs for two years. The Google X program aims to produce drones that can deliver items.[151]

July 16, 2015, A NASA Langley fixed-wing Cirrus SR22 aircraft, flown remotely from the ground, operated by NASA's Langley Research Center in Hampton and a hexacopter drone delivered pharmaceuticals and other medical supplies to an outdoor free clinic at the Wise County Fairgrounds, Virginia. The aircraft picked up 10 pounds of pharmaceuticals and supplies from an airport in Tazewell County in southwest Virginia and delivered the medicine to the Lonesome Pine Airport in Wise County. The aircraft had a pilot on board for safety. The supplies went to a crew, which separated the supplies into 24 smaller packages to be delivered by small, unmanned drone to the free clinic, during a number of flights over two hours. A company pilot controlled the hexacopter, which lowered the pharmaceuticals to the ground by tether. Health care professionals received the packages, then distributed the medications to the appropriate patients.[152]

Farms

A Yamaha R-MAX, a UAV that has been used for aerial application in Japan

UAV is also now becoming the invaluable tool by farmers in other aspect of farming, such as monitoring livestock, crops and water levels. Farmers also use it for fast data gathering on crop health, improving yield plus reducing input cost. Sophisticated UAV has also been used to create 3D image of the landscape to plan for future expansions and upgrading [155]

Future potential

Krossblade SkyProwler transformer UAV for research into vertical take-off and landing technologies for aircraft

Solar-powered atmospheric satellites ("atmosats") designed for operating at altitudes exceeding 20 km (12 miles, or 60,000 feet) for as long as five years can perform duties more economically and with more versatility than low earth orbit satellites.[159] Likely applications include weather monitoring, disaster recovery, earth imaging, and communications.[159]

The European Union says drone market share could be up to 10% of aviation in 10 years, and the EU suggests streamlining research and development efforts.[160]

Drones, as low-cost flying machines, make great rescue tools. They can look and go places people cannot, or at least not safely; with infrared cameras, they can sometimes see beyond what human eyes can. In Houston, the World Animal Awareness Society plans to use them to track stray dogs, combining a drone's utility as a mapping device with its rescue abilities.[161]

In 2015, the US Navy is testing swarm behaviour with 9 small Coyote drones.[162][163][164]

Design and development considerations

UAV design and production is a global activity with manufacturers all across the world. The United States and Israel were initial pioneers in this technology, and U.S. manufacturers had a market share of over 60% in 2006, with U.S. market share due to increase by 5–10% through 2016.[165] Northrop Grumman and General Atomics are the dominant manufacturers in this industry on the strength of the Global Hawk and Predator/Mariner systems.[165] According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Israeli companies were behind 41% of all UAVs exported in 2001-2011.[166] The European market share represented 4% of global revenue in 2006.[165]In December 2013, the Federal Aviation Administration announced its selections six states that will host test sites emphasizing respective research goals: Alaska (sites with a wide variety of climates), Nevada (formulating standards for air traffic control and UAV operators), New York (integrating UAVs into congested airspace), North Dakota (human impact; use in temperate climates), Texas (safety requirements and airworthiness testing), and Virginia (assessing operational and technical risk).[167][168]

Some universities offer UAS research and training programs or academic degrees.[39]

On October 12, 2014, the Linux Foundation and leading technology companies launched the open source Dronecode Project. The Dronecode Project goal is to help meet the needs of the growing UAV community with a neutral governance structure and coordination of funding for resources and tools which the community needs.[169]

Degree of autonomy

UAV monitoring and control at U.S. Customs and Border Protection

The development of air-vehicle autonomy has largely been driven by the military.[171]

Autonomy technology that is important to UAV development falls under the following categories:

- Sensor fusion: Combining information from different sensors for use on board the vehicle including the automatic interpretation of ground imagery [172][173]

- Communications: Handling communication and coordination between multiple agents in the presence of incomplete and imperfect information

- Path planning: Determining an optimal path for vehicle to follow while meeting certain objectives and mission constraints, such as obstacles or fuel requirements

- Trajectory generation (motion planning): Determining an optimal control maneuver to take in order to follow a given path or to go from one location to another

- Trajectory regulation: The specific control strategies required to constrain a vehicle within some tolerance to a trajectory

- Task allocation and scheduling: Determining the optimal distribution of tasks amongst a group of agents within time and equipment constraints

- Cooperative tactics: Formulating an optimal sequence and spatial distribution of activities between agents in order to maximize the chance of success in any given mission scenario

To some extent, the ultimate goal in the development of autonomy technology is to replace the human pilot. It remains to be seen whether future developments of autonomy technology, the perception of the technology, and, most importantly, the political climate surrounding the use of such technology will limit the development and utility of autonomy for UAV applications. Also as a result of this, synthetic vision for piloting has not caught on in the UAV arena as it did with manned aircraft. NASA utilized synthetic vision for test pilots on the HiMAT program in the early 1980s, but the advent of more autonomous UAV autopilots greatly reduced the need for this technology.[citation needed]

Interoperable UAV technologies became essential as systems proved their mettle in military operations, taking on tasks too challenging or dangerous for troops. NATO addressed the need for commonality through STANAG 4586. According to a NATO press release, the agreement began the ratification process in 1992. Its goal was to allow allied nations to easily share information obtained from unmanned aircraft through common ground control station technology.[citation needed]

Military analysts, policy makers, and academics debate the benefits and risks of lethal autonomous robots (LARs), which would be able to select targets and fire without approval of a human. Some contend that LAR drones would be more precise, less likely to kill civilians, and less prone to being hacked.[175] Heather Roff replies that LARs may not be appropriate for complex conflicts, and targeted populations would likely react angrily against them.[175] Will McCants argues that the public would be more outraged by machine failures than human error, making LARs politically implausible.[175] According to Mark Gubrud, claims that drones can be hacked are overblown and misleading, and moreover, drones are more likely to be hacked if they're autonomous, because otherwise the human operator would take control: "Giving weapon systems autonomous capabilities is a good way to lose control of them, either due to a programming error, unanticipated circumstances, malfunction, or hack, and then not be able to regain control short of blowing them up, hopefully before they've blown up too many other things and people."[176]

Autopilot systems for UAVs include:

- Ardupilot (Open-source autopilot hardware and software)

- Paparazzi Project (Open-source autopilot hardware and software)

Endurance

The endurance of a UAV is not constrained by the physiological limitations of a human pilot. The maximum flight duration of unmanned aerial vehicles varies widely.

UEL UAV-741 Wankel engine for UAV operations

Solar-electric UAVs, a concept originally championed by the AstroFlight Sunrise in 1974, have achieved endurance of several weeks.[180][181][182][183][184] Electric UAVs powered by microwave power transmission[185] or laser power beaming[186] are other proposed solutions to the endurance challenge.

In 2012, the US Air Force was promoting research into an aerial refueling capability for UAVs.[187] A UAV-UAV simulated refuelling flight using two Global Hawks was achieved in 2012.[188]

One of the uses for a high endurance UAV would be to "stare" at the battlefield for a long period of time (ARGUS-IS, Gorgon Stare, Integrated Sensor Is Structure) to produce a record of events that could then be played backwards to track where improvised explosive devices (IEDs) came from.

| UAV | Flight time | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boeing Condor | 58 hours 11 minutes | 1989 | The aircraft is currently in the Hiller Aviation Museum.

[189] |

| GNAT-750 | 40 hours | 1992 | [190][191] |

| TAM-5 | 38 hours 52 minutes | 11 August 2003 | Smallest UAV to cross the Atlantic

[192] |

| QinetiQ Zephyr Solar Electric | 54 hours | September 2007 | [193][194] |

| RQ-4 Global Hawk | 33.1 hours | 22 March 2008 | Set an endurance record for a full-scale, operational unmanned aircraft.[195] |

| QinetiQ Zephyr Solar Electric | 82 hours 37 minutes | 28–31 July 2008 | [196] |

| QinetiQ Zephyr Solar Electric | 336 hours 22 minutes | 9–23 July 2010 | [184] |

Existing UAV systems

| This section is outdated. (September 2013) |

The export of UAVs or technology capable of carrying a 500 kg payload at least 300 km is restricted in many countries by the Missile Technology Control Regime.

China has exhibited some UAV designs, but its ability to operate them is limited by the lack of high endurance domestic engines, satellite infrastructure, and operational experience.[198]

Historical events involving UAVs

- In 1981, the Israeli IAI Scout drone, is operated in combat missions by the South African Defence Force against Angola during Operation Protea.[199]

- In 1982, UAVs operated by the Israeli Air Force are instrumental during Operation Mole Cricket 19, where both IAI Scout and Tadiran Mastiff are used to identity SAM sites, while Samson decoy UAVs are used to activate and confuse Syrian radar.[199][200]

- During the Persian Gulf War, Iraqi Army forces surrendered to the UAVs of the USS Wisconsin.[201][202]

- In October 2002, a few days before the U.S. Senate vote on the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution, about 75 senators were told in closed session that Saddam Hussein had the means of delivering biological and chemical weapons of mass destruction by UAVs that could be launched from ships off the Atlantic coast to attack U.S. eastern seaboard cities. Colin Powell suggested in his presentation to the United Nations that they had been transported out of Iraq and could be launched against the U.S.[203] It was later revealed that Iraq's UAV fleet consisted of only a few outdated Czech training drones.[204] At the time, there was a vigorous dispute within the intelligence community as to whether CIA's conclusions about Iraqi UAVs were accurate. The U.S. Air Force, the agency most familiar with UAVs, denied outright that Iraq possessed any offensive UAV capability.[205]

- The first US targeted UAV killing outside the conventional battlefield took place on 3 November 2002, in the Marib district of Yemen. Six alleged terrorists were killed in their SUV by a UAV-fired missile.[206] The command centre was in Tampa, Florida, USA.

- In December 2002, the first ever dogfight involving a UAV occurred when an Iraqi MiG-25 and a U.S. RQ-1 Predator fired missiles at each other. The MiG's missile destroyed the Predator.[207]

- The U.S. deployed UAVs in Yemen to search for and kill Anwar al-Awlaki,[208] an American and Yemeni imam, firing at and failing to kill him at least once[209] before he was killed in a UAV-launched missile attack in Yemen on 30 September 2011. The targeted killing of an American citizen was unprecedented. However, nearly nine years earlier in 2002, U.S. citizen Kemal Darwish was one of six men killed by the first UAV strike outside a war zone, in Yemen.[210]

- In December 2011, Iran captured a United States' RQ-170 unmanned aerial vehicle that flew over Iran and rejected President Barack Obama's request to return it to the US.[211][212] Iranian officials claim to have recovered data from the U.S. surveillance aircraft. However, it is not clear how Iran brought it down.[213] There have also been claims that Iran spoofed the GPS signal used by the UAV[32] and hijacked it into landing on an Iranian runway.

Aircraft near-miss incidents

Canada

In March 2014, a remote-controlled helicopter was reported by the crew of a Boeing 777 flying 30 metres from their craft at Vancouver International Airport.[214]In April 2014, video taken from a camera on board a UAV showed it flying close to an airliner as it landed at the same airport.[214] A Transport Canada spokesman said his department and the RCMP were investigating.[214]

Poland

On 21 July 2015, a Lufthansa plane landing at Warsaw Chopin Airport nearly collided with a drone. The drone came in within 100 m of the plane, at an altitude of 760 m, 5 km away from the airport, near Piaseczno.[215][216][217]United Kingdom

In October 2014 it was reported that a UAV had flown within 25 metres of an ATR 72 passenger airliner on 30 May 2014.[218][219][220] The aircraft was approaching London Southend Airport and about to intercept the ILS glide slope when the copilot reported seeing a small craft flying about 100 m to the right of the aircraft.[218][219][220] The copilot and Air Traffic Controller agreed it was probably a quadcopter - it was seen flying as close as 25 m to the aircraft.[218][219][220] Southend ATC couldn't detect the craft on radar - subsequent examination of radar from other sites produced several brief but inconclusive radar signals.[220] Police were contacted, but the operator of the UAV could not be found.[218][219][220]In December 2014, investigators confirmed that they were investigating claims that a UAV came about 20 feet of an Airbus A320 landing at Heathrow on 22 July.[221] The A320 was 700 feet from landing when the craft passed 20 feet over the left wing of the aircraft - they did not collide.[221] Despite an investigation and cooperation of remote-control model aircraft club members, the operator of the aircraft could not be identified.[221] The incident was given an A rating, meaning that there had been a serious risk of collision.[221]

United States

In March 2013, an Alitalia pilot on final approach to runway 31 right at John F. Kennedy International Airport reported seeing a small UAV near his aircraft.[222][223][224][225] Both the FAA and FBI were reported to be investigating.[222][223][224][225]On March 22, 2014, US Airways Flight 4650 nearly collided with a drone while landing at Tallahassee Regional Airport. The plane, a Bombardier CRJ200, was at an altitude of 2,300 feet (700 m) when it came dangerously close to the drone, described by one of the pilots "as a camouflaged F-4 fixed-wing aircraft that was quite small". Jim Williams, head of the UAV office at the Federal Aviation Administration, said: "The risk for a small [drone] to be ingested into a passenger airline engine is very real." The Federal Bureau of Investigation was investigating the incident, which was the first known instance of a large airliner nearly colliding with a drone in the U.S.[226]

Accidents and incidents

UAVs have historically had a much higher loss rate than manned military aircraft. In addition to anti-aircraft weapons, UAVs are vulnerable to power and communications link losses.[227]Australia

In October 2013, a UAV collided with Sydney Harbour Bridge.[228] The Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) started an investigation.[228] The police returned the craft to its owner.[229]In April 2014, a triathlete was injured in an incident involving a drone that was filming a race.[230] She claimed that the drone collided with her and said "the ambulance crew took a piece of propeller from my head".[230] The owner of the UAV claimed that the athlete had been injured when she was frightened by the falling UAV and tripped.[230] Timing equipment caused interference with the operation of the UAV while it was close to people on the ground.[231] In November 2014, the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions stated that the evidence showed that the drone had crashed into the triathlete who sustained head injuries as a result. However taking into account the young age and antacedents of the drone operator the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions chose not to proceed with a charge against the operator and handed the matter back to CASA. CASA subsequently fined the operator $1,700 for flying the drone within 30 metres of people.[232]

France

In October 2013 a tourist was arrested in Paris[233] and fined 400 euro for “operating an aircraft non-compliant with safety laws”.[233]In October and November 2014 unidentified UAVs were seen flying near 13 nuclear power plants.[234] The Secretariat-General for National Defence and Security issued a statement that the flights were an "organized provocation".[234]

India

In May 2014 Francescos' Pizza of Mumbai made a test delivery from a branch in Lower Parel to the roof of a building in Worli.[235] Police in Mumbai began an investigation on the grounds that security clearances had not been sought.[236]Republic of Ireland

In 2012, a theatre group flew Parrot AR.Drones in Dublin[237] to film video for an exhibit.[237] The Irish Aviation Authority stated that this was prohibited as Dublin city is classed as a restricted area.[238]South Africa

In June 2013, police officers apprehended a man who flew a multicopter outside the hospital that Nelson Mandela was in.[239] The equipment and footage were confiscated by the police.[240]United Kingdom

In April 2014, a man pleaded guilty of flying a small UAV within 50 m of a submarine testing facility.[241][241] He claimed that he had been flying a mile from the base but had lost radio contact with the craft.[241] He was fined £800 and ordered to pay legal costs of £3,500.[241] The CAA claimed that the case raised safety issues related to flying unmanned aircraft.[241]United States

In August 2013, a UAV filming events at the Virginia Bull Run in Dinwiddie County, Virginia crashed into the crowd, causing minor injuries.[242][243]Ice hockey fans were celebrating a victory outside the Staples Center in 2014 when a UAV was seen flying over the crowd.[244][245][246] The crowd threw objects at the UAV, bringing it close enough to the ground for members of the crowd to grab it.[244][245] Claims were made that the UAV belonged to the Los Angeles Police Department, but the LAPD denied this.[244][245]

In January 2015, a DJI Phantom crashed in the grounds of the White House.[247] The operator had flown it while drunk and lost control of it.[247]

In July 2015 firefighting aircraft were grounded for 26 minutes in Southern California because of fears of collisions with five UAVs that had been seen in the area.[248] It was the fourth time in as many weeks that drones had hampered firefighters in Southern California.[248]

In September 2015 a drone crashed into empty seating at the US Open at Louis Armstrong Stadium, causing no injuries according to the USTA.[249] It happened during a match between Flavia Pennetta and Monica Niculescu.[249] A teacher named Daniel Verley was arrested on charges of reckless endangerment, reckless operation of a drone and operating a drone outside of a prescribed area in a New York city park.[249] He was released and ordered to attend court at a later date.[249] It is expressly forbidden to bring drones onto the grounds of the National Tennis Center.[249]

In October 2015 Daniel Verley was sentenced to community service, involving tutoring disenfranchised students.[250] He had cooperated fully with the investigation.[250]

UAVs in the US military

Main article: UAVs in the U.S. military

As of January 2014, the U.S. military operates a large number of unmanned aerial systems: 7,362 RQ-11B Ravens; 145 AeroVironment RQ-12A Wasps; 1,137 AeroVironment RQ-20A Pumas; and 306 RQ-16 T-Hawk Small UAS systems and 246 Predators and MQ-1C Grey Eagles; 126 MQ-9 Reapers; 491 RQ-7 Shadows; and 33 RQ-4 Global Hawk large systems.[251]

The use of drones in the military is expected to increase in coming

years because UAVs curb defense spending. The MQ-9 Reaper costs $12

million while an F-22 costs over $120 million.[252]UAVs in popular culture

Main article: List of films featuring drones

- Toys (1992) depicts unwitting child soldiers in training to fly UAVs.

- UAVs were used[clarification needed] in episodes of the science-fiction television series, Stargate SG-1 (1997-2007) and Dark Angel (2000-2002).

- A UCAV AI, called EDI, was central to the sci-fi action film Stealth (2005).

- UAVs also feature in video games, such as Tom Clancy's Ghost Recon (2001-), Battlefield (2002-), Call of Duty (2003-), F.E.A.R. (2005), and inFamous (2009).[253]

- An MQ-9 reaper controlled by a rogue supercomputer appears in the film Eagle Eye (2008).

- The hapless would-be terrorists in the film Four Lions (2010) are targeted by and attempt to shoot down an RQ-1 Predator.

- The Bourne Legacy (2012 film) features a Predator UAV pursuing the protagonists.

- An episode of the TV show Castle, first broadcast in May 2013, featured a UAV hacked by terrorists.[254]

- The British movie Hummingbird (2013) ends with ambiguity as to whether the main protagonist is taken down by a drone or not.

- 24: Live Another Day, the ninth season of "24", revolves around the usage of UAVs resembling the BAE Systems Taranis by terrorists who have created a device to override control from a military base.

UAE Drones for Good Award

In 2014, the government of the United Arab Emirates announced an annual international competition and $1 million award, UAE Drones for Good, aiming to encourage useful and positive applications for UAV technology in applications such as in search and rescue, civil defence and conservation. The 2015 award was won by Swiss company Flyability.See also

- List of unmanned aerial vehicles

- Micro air vehicle

- Miniature UAV

- Radio-controlled aircraft

- Satellite Sentinel Project

- Quadcopter

- International Aerial Robotics Competition

- ParcAberporth

References

- "Happiness is a warm TV - What to Watch on Monday: A drone strike on 'Castle' - newsobserver.com blogs". Blogs.newsobserver.com. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Unmanned aerial vehicles. |

- History of WWI-era UAVs – Remote Piloted Aerial Vehicles : The "Aerial Target" and "Aerial Torpedo" in the USA

- Center for Unmanned Aircraft Systems, a National Science Foundation Industry & University Cooperative Research Center

- Defense Update reports about UAV employment in Persistent Surveillance

- Breaking news for professional RPAS operators

- Drones in Domestic Surveillance Operations: Fourth Amendment Implications and Legislative Responses Congressional Research Service, 6 September 2012.

- Integration of Civil Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) in the National Airspace System Roadmap

- Unmanned Systems Technology, Directory of UAV technical components

- UVS International Non Profit Organization representing manufacturers of unmanned vehicle systems (UVS), subsystems and critical components for UVS and associated equipment, as well as companies supplying services with or for UVS, research organizations and academia.

- List of organizations approved to fly non-recreational drones in the United States, as of June 19, 2014

- DoD UAS Roadmap 2005–2030

- DoD Unmanned Systems Integrated Roadmap 2009

- The Remote Control Aerial Platform Association, commercial UAS operators

- [13], the most important stories about UAV's

- Impact of drones in our daily life

|

||

|

|||

|

When used, UAVs should generally perform missions characterized by the three Ds: dull, dirty, and dangerous.

The War of Attrition was also notable for the first use of UAVs, or unmanned aerial vehicles, carrying reconnaissance cameras in combat.

During the Yom Kippur War the Israelis used Teledyne Ryan 124 R RPVs along with the home-grown Scout and Mastif UAVs for reconnaissance, surveillance and as decoys to draw fire from Arab SAMs. This resulted in Arab forces expending costly and scarce missiles on inappropriate targets [...].

Tim Pool, an Occupy Wall Street protester, has acquired a Parrot AR.Drone he amusingly calls the "occucopter"

FBI Director Robert Mueller said today the bureau was surveiling the United States with drones. The revelation was during an FBI oversight hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee and comes as the bureau, along with the National Security Agency, are on the defensive about revelations that they are obtaining metadata on Americans’ phone records and Americans’ private data from companies like Google, Facebook, Microsoft, and others. The FBI is not alone in monitoring the U.S. with drones.

Although they malfunction less often than they used to, they still crash at a higher rate than other military aircraft. Of the 269 Predators acquired by the Air Force over the past two decades, more than half have wrecked in major accidents, records show.

- Unmanned aerial vehicle (redirect from Drone aircraft)commonly known as a drone and also referred by several other names is an aircraft without a human pilot aboard. The flight of UAVs may be controlled134 KB (13,774 words) - 19:19, 30 October 2015

No comments:

Post a Comment