Since I and 100 of my friends have been given the Dzogchen initiation and empowerment in Mt. Shasta by Lama Wangdor who I met in Rewalsar, India in early 1986 I thought I would start with Dzogchen.

begin quote from:

Dzogchen

Dzogchen

Dzogchen Tibetan name Tibetan རྫོགས་ཆེན་

showTranscriptions

Chinese name Traditional Chinese 大究竟、

大圓滿、

大成就 Simplified Chinese 大究竟、

大圆满、

大成就

showTranscriptions

Part of a series on Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism portal

Tibetan Buddhism portal

Part of a series on Bon

Part of a series on Vajrayana Buddhism

Vajrayana Buddhism portal

Vajrayana Buddhism portal

Part of a series on Mahāyāna Buddhism

Mahayana Buddhism

Mahayana Buddhism

Part of a series on Buddhism

Dzogchen (Wylie: rdzogs chen) or "Great Perfection", Sanskrit: अतियोग, is a tradition of teachings in Tibetan Buddhismaimed at discovering and continuing in the natural primordial state of being.[1] It is a central teaching of the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism and of Bon.[quote 1] In these traditions, Dzogchen is the highest and most definitive path of the nine vehicles to liberation.[2]

| Dzogchen | |||

| Tibetan name | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tibetan | རྫོགས་ཆེན་ | ||

| |||

| Chinese name | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 大究竟、 大圓滿、 大成就 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 大究竟、 大圆满、 大成就 | ||

| |||

| Part of a series on |

| Tibetan Buddhism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Bon |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Vajrayana Buddhism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Mahāyāna Buddhism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

Dzogchen (Wylie: rdzogs chen) or "Great Perfection", Sanskrit: अतियोग, is a tradition of teachings in Tibetan Buddhismaimed at discovering and continuing in the natural primordial state of being.[1] It is a central teaching of the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism and of Bon.[quote 1] In these traditions, Dzogchen is the highest and most definitive path of the nine vehicles to liberation.[2]

CONTENTS

[hide]

- 1Etymology

- 2Origins and history

- 2.1Traditional accounts

- 2.2Historical origins and development

- 2.2.1Tibetan Empire (7th–9th century)

- 2.2.2Traditional classification of Dzogchen texts (9th–14th century)

- 2.2.3Origins and Dunhuan texts (8th–10th century)

- 2.2.4Early Dzogchen – the Mind series (9–10th century)

- 2.2.5Transformation – the Space and Instruction series (11th–14th century)

- 2.2.6Longchenpa's Seven Treasuries (14th century)

- 2.2.7Later termas

- 2.2.8Modern times

- 2.3Kagyu and Gelugpa

- 3Conceptual background

- 4Teachings and practice

- 5See also

- 6Notes

- 7Quotes

- 8References

- 9Sources

- 10Further reading

- 11External links

[hide]

- 1Etymology

- 2Origins and history

- 2.1Traditional accounts

- 2.2Historical origins and development

- 2.2.1Tibetan Empire (7th–9th century)

- 2.2.2Traditional classification of Dzogchen texts (9th–14th century)

- 2.2.3Origins and Dunhuan texts (8th–10th century)

- 2.2.4Early Dzogchen – the Mind series (9–10th century)

- 2.2.5Transformation – the Space and Instruction series (11th–14th century)

- 2.2.6Longchenpa's Seven Treasuries (14th century)

- 2.2.7Later termas

- 2.2.8Modern times

- 2.3Kagyu and Gelugpa

- 3Conceptual background

- 4Teachings and practice

- 5See also

- 6Notes

- 7Quotes

- 8References

- 9Sources

- 10Further reading

- 11External links

ETYMOLOGY[EDIT]

Dzogchen is composed of two terms:

The term initially referred to the "highest perfection" of deity visualisation, after the visualisation has been dissolved and one rests in the natural state of the innately luminous and pure mind.[3][web 1] In the 10th and 11th century, Dzogchen emerged as a separate tantric vehicle in the Nyingma tradition,[web 1] used synonymously with the Sanskrit term ati yoga (primordial yoga).[4]

According to van Schaik, in the 8th-century tantra Sarvabuddhasamāyoga

According to the 14th Dalai Lama, the term dzogchen may be a rendering of the Sanskrit term mahāsandhi.[5]

According to Anyen Rinpoche, the true meaning is that the student must take the entire path as an interconnected entity of equal importance. Dzogchen is perfect because it is an all-inclusive totality that leads to middle way realization, in avoiding the two extremes of nihilism and eternalism. It classifies outer, inner and secret teachings, which are only separated by the cognitive construct of words and completely encompasses Tibetan Buddhist wisdom.[6] It can be as easy as taking Bodhicittaas the method, and failing this is missing an essential element to accomplishment.[7]

Dzogchen is composed of two terms:

The term initially referred to the "highest perfection" of deity visualisation, after the visualisation has been dissolved and one rests in the natural state of the innately luminous and pure mind.[3][web 1] In the 10th and 11th century, Dzogchen emerged as a separate tantric vehicle in the Nyingma tradition,[web 1] used synonymously with the Sanskrit term ati yoga (primordial yoga).[4]

According to van Schaik, in the 8th-century tantra Sarvabuddhasamāyoga

According to the 14th Dalai Lama, the term dzogchen may be a rendering of the Sanskrit term mahāsandhi.[5]

According to Anyen Rinpoche, the true meaning is that the student must take the entire path as an interconnected entity of equal importance. Dzogchen is perfect because it is an all-inclusive totality that leads to middle way realization, in avoiding the two extremes of nihilism and eternalism. It classifies outer, inner and secret teachings, which are only separated by the cognitive construct of words and completely encompasses Tibetan Buddhist wisdom.[6] It can be as easy as taking Bodhicittaas the method, and failing this is missing an essential element to accomplishment.[7]

ORIGINS AND HISTORY[EDIT]

Traditional accounts[edit]

Nyingma tradition[edit]

According to the Nyingma tradition,[8] the primordial Buddha Samantabhadra taught Dzogchen to the Buddha Vajrasattva, who transmitted it to the first human lineage holder, the Indian Garab Dorje (fl. 55 CE).[3][8] According to tradition, the Dzogchen teachings were brought to Tibet by Padmasambhava in the late 8th and early 9th centuries. He was aided by two Indian masters, Vimalamitra and Vairocana.[9] According to the Nyingma tradition, they transmitted the Dzogchen teachings in three distinct series, namely the Mind Series (sem-de), Space series (long-de), and Secret Instruction Series (men-ngak-de).[8] According to tradition, these teachings were concealed shortly afterward, during the 9th century, when the Tibetan empire disintegrated.[9] From the 10th century forward, innovations in the Nyingma tradition were largely introduced historically as revelations of these concealed scriptures, known as terma.[9]

According to the Nyingma tradition,[8] the primordial Buddha Samantabhadra taught Dzogchen to the Buddha Vajrasattva, who transmitted it to the first human lineage holder, the Indian Garab Dorje (fl. 55 CE).[3][8] According to tradition, the Dzogchen teachings were brought to Tibet by Padmasambhava in the late 8th and early 9th centuries. He was aided by two Indian masters, Vimalamitra and Vairocana.[9] According to the Nyingma tradition, they transmitted the Dzogchen teachings in three distinct series, namely the Mind Series (sem-de), Space series (long-de), and Secret Instruction Series (men-ngak-de).[8] According to tradition, these teachings were concealed shortly afterward, during the 9th century, when the Tibetan empire disintegrated.[9] From the 10th century forward, innovations in the Nyingma tradition were largely introduced historically as revelations of these concealed scriptures, known as terma.[9]

Bon tradition[edit]

In the fourteenth century, Loden Nyingpo revealed a terma containing the story of Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche.[10] According to this terma, Dzogchen originated with the founder of the Bon tradition, Tonpa Shenrab, who lived 18,000 years ago, ruling the kingdom of Tazik, which supposedly lay west of Tibet.[8] He transmitted these teachings to the region of Zhang-zhung, the far western part of the Tibetan cultural world.[8][9] The earliest Bon literature only exists in Tibetan manuscripts, the earliest of which can be dated to the 11th century.[11] The Bon tradition also has a threefold classification, namely Dzogchen, A-tri, and the "Zhang-zhung Aural Lineage (zhang-zhung nyen-gyu).[8]

In the fourteenth century, Loden Nyingpo revealed a terma containing the story of Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche.[10] According to this terma, Dzogchen originated with the founder of the Bon tradition, Tonpa Shenrab, who lived 18,000 years ago, ruling the kingdom of Tazik, which supposedly lay west of Tibet.[8] He transmitted these teachings to the region of Zhang-zhung, the far western part of the Tibetan cultural world.[8][9] The earliest Bon literature only exists in Tibetan manuscripts, the earliest of which can be dated to the 11th century.[11] The Bon tradition also has a threefold classification, namely Dzogchen, A-tri, and the "Zhang-zhung Aural Lineage (zhang-zhung nyen-gyu).[8]

Historical origins and development[edit]

Tibetan Empire (7th–9th century)[edit]

The written history of Tibet begins in the early 7th century, when the Tibetan kingdoms were united, and Tibet expanded throughout large parts of Central Asia.[12] Songtsen Gampo (reign ca.617-649/50) conquered the kingdom of Zhangzhung in western Tibet, dominated Nepal, and threatened the Chinese dominance in strategically important areas of the Silk Road.[13] He is also credited with the adoption of a writing system, the establishment of a legal code, and the introduction of Buddhism, though it probably only played a minor role.[13] Tri Songdetsen (742-ca.797) adopted Buddhism, but also maintained the martial traditions of the Tibetan empire.[13] The Tibetans controlled Dunhuang, a major Buddhist center, from the 780s until the mid-ninth century.[14] Halfway through the 9th century the Tibetan empire collapsed.[15] Royal patronage of Buddhism was lost, leading to a decline of Buddhism in Tibet,[15][16] only to recover with the renaissance of Tibetan culture occurring from the late 10th century to the early 12th century,[11] known as the later dissemination of Buddhism.[11]

The written history of Tibet begins in the early 7th century, when the Tibetan kingdoms were united, and Tibet expanded throughout large parts of Central Asia.[12] Songtsen Gampo (reign ca.617-649/50) conquered the kingdom of Zhangzhung in western Tibet, dominated Nepal, and threatened the Chinese dominance in strategically important areas of the Silk Road.[13] He is also credited with the adoption of a writing system, the establishment of a legal code, and the introduction of Buddhism, though it probably only played a minor role.[13] Tri Songdetsen (742-ca.797) adopted Buddhism, but also maintained the martial traditions of the Tibetan empire.[13] The Tibetans controlled Dunhuang, a major Buddhist center, from the 780s until the mid-ninth century.[14] Halfway through the 9th century the Tibetan empire collapsed.[15] Royal patronage of Buddhism was lost, leading to a decline of Buddhism in Tibet,[15][16] only to recover with the renaissance of Tibetan culture occurring from the late 10th century to the early 12th century,[11] known as the later dissemination of Buddhism.[11]

Traditional classification of Dzogchen texts (9th–14th century)[edit]

Traditionally, the early Dzogchen literature is categorized into three categories,[3] which more or less reflect the historical development of Dzogchen:

- Semde (Wylie: sems sde; Skt: cittavarga), the "Mind series"; this category contains the earliest (proto) Dzogchen teachings.[17]Tradition attributes them to Padmasmabhava and his consorts, and dates them to the 8th century,[9] but they first appeared in the 9th century, written by Tibetans;[11]

- Longde (Wylie: klong sde; Skt: abhyantaravarga), the series of Space; this series reflects the developments of the 11th-14th centuries, when new Buddhist techniques and doctrines were introduced into Tibet;[3]

- Menngagde (Wylie: man ngag sde, Skt: upadeshavarga), the series of secret Oral Instructions, also known as Seminal Heart or Nyingthik (snying thig), also reflects the developments of the 11th-14th centuries; this series has overshadowed the other two. This division focuses on two aspects of practice: kadag trekchö, "the cutting through of primordial purity", and lhündrub tögal, "the direct crossing of spontaneous presence".[18]

Traditionally, the early Dzogchen literature is categorized into three categories,[3] which more or less reflect the historical development of Dzogchen:

- Semde (Wylie: sems sde; Skt: cittavarga), the "Mind series"; this category contains the earliest (proto) Dzogchen teachings.[17]Tradition attributes them to Padmasmabhava and his consorts, and dates them to the 8th century,[9] but they first appeared in the 9th century, written by Tibetans;[11]

- Longde (Wylie: klong sde; Skt: abhyantaravarga), the series of Space; this series reflects the developments of the 11th-14th centuries, when new Buddhist techniques and doctrines were introduced into Tibet;[3]

- Menngagde (Wylie: man ngag sde, Skt: upadeshavarga), the series of secret Oral Instructions, also known as Seminal Heart or Nyingthik (snying thig), also reflects the developments of the 11th-14th centuries; this series has overshadowed the other two. This division focuses on two aspects of practice: kadag trekchö, "the cutting through of primordial purity", and lhündrub tögal, "the direct crossing of spontaneous presence".[18]

Origins and Dunhuan texts (8th–10th century)[edit]

According to Sam van Schaik, who studies early Dzogchen manuscripts from the Dunhuang caves, the Dzogchen texts are influenced by earlier Mahayana sources such as the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra and Indian Buddhist Tantras with their teaching of emptiness and luminosity, which in Dzogchen texts are presented as 'ever-purity' (ka-dag) and 'spontaneous presence' (lhun-grub).[19]

Sam van Schaik also notes that there is a discrepancy between the histories as presented by the traditions, and the picture that emerges from those manuscripts.[17][web 1]

There is no record of Dzogchen as a separate tradition or vehicle prior to the 10th century,[8] although the terms atiyoga (as a higher practice than Tantra) and dzogchen do appear in 8th and 9th century Indian tantric texts.[11] There is also no independent attestation of the existence of any separate traditions or lineages under the name of Dzogchen outside of Tibet,[11] and it may be a unique Tibetan teaching,[8][3] drawing on multiple influences, including both native Tibetan non-Buddhist beliefs and Chinese and Indian Buddhist teachings.[3]

According to van Schaik, the term atiyoga first appeared in the 8th century, in an Indian tantra called Sarvabuddhasamāyoga.[note 1] In this text, Anuyoga is the stage of yogic bliss, while Atiyoga is the stage of the realization of the "nature of reality."[web 1] According to van Schaik, this fits with the three stages of deity yoga as described in a work attributed to Padmasambhava: development (kye), perfection (dzog) and great perfection (dzogchen).[web 1] Atiyoga here is not a vehicle, but a stage or aspect of yogic practice.[web 1] In Tibetan sources, until the 10th century Atiyoga is characterized as a "mode" (tshul) or a "view" (lta ba), which is to be applied within deity yoga.[web 1]

According to van Schaik, the concept of dzogchen, "great perfection," first appeared as the culmination of the meditative practice of deity yoga[note 2] around the 8th century.[web 1] The term dzogchen was likely taken from the Guhyagarbhatantra. This tantra describes, as other tantras, how in the creation stage one generates a visualisation of a deity and its mandala. This is followed by the completion stage, in which one dissolves the deity and the mandala into oneself, merging oneself with the deity. In the Guhyagarbhatantra and some other tantras, there follows a stage called rdzogs chen, in which one rests in the natural state of the innately luminous and pure mind.[3]

In the 9th and 10th centuries deity yoga was contextualized in Dzogchen in terms of nonconceptuality, nonduality and the spontaneous presence of the enlightened state.[web 1] Some Dunhuang texts dated at the 10th century show the first signs of a developing nine vehicles system. Nevertheless, Anuyoga and Atiyoga are still regarded then as modes of Mahāyoga practice.[web 1] Only in the 11th century came Atiyoga to be threatened as a separate vehicle, at least in the newly emerging Nyingma tradition.[web 1] Nevertheless, even in the 13th century (and later) the idea of Atiyoga as a vehicle was controversial in other Buddhist schools.[web 1] Van Schaik quotes Sakya Pandita as writing, in his Distinguishing the Three Vows:

According to Sam van Schaik, who studies early Dzogchen manuscripts from the Dunhuang caves, the Dzogchen texts are influenced by earlier Mahayana sources such as the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra and Indian Buddhist Tantras with their teaching of emptiness and luminosity, which in Dzogchen texts are presented as 'ever-purity' (ka-dag) and 'spontaneous presence' (lhun-grub).[19]

Sam van Schaik also notes that there is a discrepancy between the histories as presented by the traditions, and the picture that emerges from those manuscripts.[17][web 1]

There is no record of Dzogchen as a separate tradition or vehicle prior to the 10th century,[8] although the terms atiyoga (as a higher practice than Tantra) and dzogchen do appear in 8th and 9th century Indian tantric texts.[11] There is also no independent attestation of the existence of any separate traditions or lineages under the name of Dzogchen outside of Tibet,[11] and it may be a unique Tibetan teaching,[8][3] drawing on multiple influences, including both native Tibetan non-Buddhist beliefs and Chinese and Indian Buddhist teachings.[3]

According to van Schaik, the term atiyoga first appeared in the 8th century, in an Indian tantra called Sarvabuddhasamāyoga.[note 1] In this text, Anuyoga is the stage of yogic bliss, while Atiyoga is the stage of the realization of the "nature of reality."[web 1] According to van Schaik, this fits with the three stages of deity yoga as described in a work attributed to Padmasambhava: development (kye), perfection (dzog) and great perfection (dzogchen).[web 1] Atiyoga here is not a vehicle, but a stage or aspect of yogic practice.[web 1] In Tibetan sources, until the 10th century Atiyoga is characterized as a "mode" (tshul) or a "view" (lta ba), which is to be applied within deity yoga.[web 1]

According to van Schaik, the concept of dzogchen, "great perfection," first appeared as the culmination of the meditative practice of deity yoga[note 2] around the 8th century.[web 1] The term dzogchen was likely taken from the Guhyagarbhatantra. This tantra describes, as other tantras, how in the creation stage one generates a visualisation of a deity and its mandala. This is followed by the completion stage, in which one dissolves the deity and the mandala into oneself, merging oneself with the deity. In the Guhyagarbhatantra and some other tantras, there follows a stage called rdzogs chen, in which one rests in the natural state of the innately luminous and pure mind.[3]

In the 9th and 10th centuries deity yoga was contextualized in Dzogchen in terms of nonconceptuality, nonduality and the spontaneous presence of the enlightened state.[web 1] Some Dunhuang texts dated at the 10th century show the first signs of a developing nine vehicles system. Nevertheless, Anuyoga and Atiyoga are still regarded then as modes of Mahāyoga practice.[web 1] Only in the 11th century came Atiyoga to be threatened as a separate vehicle, at least in the newly emerging Nyingma tradition.[web 1] Nevertheless, even in the 13th century (and later) the idea of Atiyoga as a vehicle was controversial in other Buddhist schools.[web 1] Van Schaik quotes Sakya Pandita as writing, in his Distinguishing the Three Vows:

Early Dzogchen – the Mind series (9–10th century)[edit]

Most of the early Dzogchen literature, which are claimed to be "translations", are original compositions from a much later date than the 8th century.[11] According to Germano, the Dzogchen-tradition first appeared in the first half of the 9th century, with a series of short texts attributed to Indian saints.[11] They were codified into a canon of eighteen texts which were referred to as "mind oriented" (sems phyogs), and later became known as "mind series" (sems de). [11]

The mind series reflect the teachings of early Dzogchen, which rejected all forms of practice, and asserted that striving for liberation would simply create more delusion.[3][11] One has simply to recognize the nature of one's own mind, which is naturally empty (stong pa), luminous ('od gsal ba), and pure.[3] According to Germano, its characteristic language, which is marked by naturalism and negation, is already pronounced in some Indian tantras.[11] Nevertheless, these texts are still inextricably bound up with tantric Mahayoga, with its visualisations of deities and mandals, and complex initiations.[11]

During the 9th and 10th centuries these texts, which represent the dominant form of the tradition in the 9th and 10th centuries,[11] were gradually transformed into full-fledged tantras, culminating in the Kulayarāja Tantra (kun byed rgyal po, "The All-Creating King"[11]), in the last half of the 10th or the first half of the 11th century.[11]According to Germano, this tantra was historically perhaps the most important and widely quoted of all Dzogchen scriptures.[11]

Most of the early Dzogchen literature, which are claimed to be "translations", are original compositions from a much later date than the 8th century.[11] According to Germano, the Dzogchen-tradition first appeared in the first half of the 9th century, with a series of short texts attributed to Indian saints.[11] They were codified into a canon of eighteen texts which were referred to as "mind oriented" (sems phyogs), and later became known as "mind series" (sems de). [11]

The mind series reflect the teachings of early Dzogchen, which rejected all forms of practice, and asserted that striving for liberation would simply create more delusion.[3][11] One has simply to recognize the nature of one's own mind, which is naturally empty (stong pa), luminous ('od gsal ba), and pure.[3] According to Germano, its characteristic language, which is marked by naturalism and negation, is already pronounced in some Indian tantras.[11] Nevertheless, these texts are still inextricably bound up with tantric Mahayoga, with its visualisations of deities and mandals, and complex initiations.[11]

During the 9th and 10th centuries these texts, which represent the dominant form of the tradition in the 9th and 10th centuries,[11] were gradually transformed into full-fledged tantras, culminating in the Kulayarāja Tantra (kun byed rgyal po, "The All-Creating King"[11]), in the last half of the 10th or the first half of the 11th century.[11]According to Germano, this tantra was historically perhaps the most important and widely quoted of all Dzogchen scriptures.[11]

Transformation – the Space and Instruction series (11th–14th century)[edit]

Early Dzogchen was completely transformed in the 11th century,[11] with the renaissance of Tibetan culture occurring from the late 10th century to the early 12th century,[11]known as the later dissemination of Buddhism.[11] New techniques and doctrines were introduced from India, resulting in new schools of Tibetan Buddhism,[3][11]and radical new developments in Dzogchen doctrine and practice, with a growing emphasis on meditative practice.[3] The older Bon and Nyingma traditions incorporated these new influences through the process of Treasure revelation.[11] Especially the yogini tantras were influential, involving horrific imagery and violent rituals, erotic imagery, and sexual and somatic practices.[11] These influences are reflected in the rise of subtle body representations and practices, new pantheons of wrathful and erotic Buddhas, increasingly antinomium rhetorics, and a focus on death-motifs.[20]

These influences were incorporated in several movements such as the "Secret Cycle" (gsang skor),[21] "Ultra Pith" (yang tig),[21] "Brahmin's tradition" (bram ze'i lugs),[21][21] the "Space Class Series,"[3] and especially the "Instruction Class series",[3] which culminated in the "Seminal Heart" (snying thig), which emerged in the late 11th and early 12th century.[21]

The "Seminal Heart" belongs to the "Instruction series."[21] The main texts of the instruction series are the so-called seventeen tantras and the two "seminal heart" collections, namely the bi ma snying thig (Vima Nyingthig,[22] "Seminal Heart of Vimalamitra") and the mkha' 'gro snying thig (Khandro nyingthig,[22] "Seminal Heart of the Dakini").[3] The "Seminal Heart of Vimalamitra" is attributed to Vimalamitra, but was largely composed by their discoverers, in the 11th and 12th century.[23] The "Seminal Heart of the Dakini" was produced by Tsultrim Dorje (Tshul khrims rdo rje)(1291-1315/17).[23]

The Seminal Heart teachings became the dominant Dzogchen-teachings,[24] but was also criticized by conservative strands within the Nyingma-school.[24] The most important Nyingma of the 12th century, Nyangrel Nyingma Özer (Nyang ral nyi ma 'od zer, 1136-1204[note 3] ) developed his "Crown Pith" (spyi ti) to reassert the older traditions in a new form.[24] His writings, which were also presented as revelations, are marked by a relative absence of yogini tantra influence, and transcend the prescriptions of specific practices, as well as the rhetoric of violence, sexuality and transgression.[24]

Early Dzogchen was completely transformed in the 11th century,[11] with the renaissance of Tibetan culture occurring from the late 10th century to the early 12th century,[11]known as the later dissemination of Buddhism.[11] New techniques and doctrines were introduced from India, resulting in new schools of Tibetan Buddhism,[3][11]and radical new developments in Dzogchen doctrine and practice, with a growing emphasis on meditative practice.[3] The older Bon and Nyingma traditions incorporated these new influences through the process of Treasure revelation.[11] Especially the yogini tantras were influential, involving horrific imagery and violent rituals, erotic imagery, and sexual and somatic practices.[11] These influences are reflected in the rise of subtle body representations and practices, new pantheons of wrathful and erotic Buddhas, increasingly antinomium rhetorics, and a focus on death-motifs.[20]

These influences were incorporated in several movements such as the "Secret Cycle" (gsang skor),[21] "Ultra Pith" (yang tig),[21] "Brahmin's tradition" (bram ze'i lugs),[21][21] the "Space Class Series,"[3] and especially the "Instruction Class series",[3] which culminated in the "Seminal Heart" (snying thig), which emerged in the late 11th and early 12th century.[21]

The "Seminal Heart" belongs to the "Instruction series."[21] The main texts of the instruction series are the so-called seventeen tantras and the two "seminal heart" collections, namely the bi ma snying thig (Vima Nyingthig,[22] "Seminal Heart of Vimalamitra") and the mkha' 'gro snying thig (Khandro nyingthig,[22] "Seminal Heart of the Dakini").[3] The "Seminal Heart of Vimalamitra" is attributed to Vimalamitra, but was largely composed by their discoverers, in the 11th and 12th century.[23] The "Seminal Heart of the Dakini" was produced by Tsultrim Dorje (Tshul khrims rdo rje)(1291-1315/17).[23]

The Seminal Heart teachings became the dominant Dzogchen-teachings,[24] but was also criticized by conservative strands within the Nyingma-school.[24] The most important Nyingma of the 12th century, Nyangrel Nyingma Özer (Nyang ral nyi ma 'od zer, 1136-1204[note 3] ) developed his "Crown Pith" (spyi ti) to reassert the older traditions in a new form.[24] His writings, which were also presented as revelations, are marked by a relative absence of yogini tantra influence, and transcend the prescriptions of specific practices, as well as the rhetoric of violence, sexuality and transgression.[24]

Longchenpa's Seven Treasuries (14th century)[edit]

A pivotal figure in the history of Dzogchen was Longchenpa Rabjampa (1308-1364, possibly 1369). He systematized the Seminal Heart teachings[24] and other collections of texts that were circulating at the time in Tibet,[28] in the Seven Treasuries (mdzod bdun), the "Trilogy of Natural Freedom" (rang grol skor gsum), and the Trilogy of Natural Ease (ngal gso skor gsum).[3][24] Longchenpa refined the terminology and interpretations, and integrated the Seminal Heart teachings with broader Mahayana literature.[24]

Malcolm Smith notes that Longchenpa's Tshig don mdzod, the "Treasury of Subjects,"[web 2] was preceded by several other texts by other authors dealing with the same topics.[web 2] Smith mentions the 12th century text "The Eleven Subjects of The Great Perfection"[note 4] by Nyi 'bum. This itself was derived from the eighth and final chapter of the commentary to The String of Pearls Tantra.[web 2]

Nyi 'bum's "Eleven Subjects" is the basis for Longchenpa's "Treasury of Subjects" as well as Rigzin Godem's "The Aural Lineage of Vimalamitra"[note 5][web 2] from the Gongpa Zangthal.[web 2]

According to Smith, Nyi 'bum's "Eleven Subjects" provided the outline upon which Longchenpa's "Treasury of Subjects" was based, using the general sequence of citations, and even copying or reworking entire passages.[web 2] According to Smith, Nyi 'bum's "Eleven Subjects" was transmitted in a close circle of disciples, with very little outside contact, whereas Longchenpa's "Treasury of Subjects" contains responses to 14th century scholastic objections to Dzogchen.[web 2]

A pivotal figure in the history of Dzogchen was Longchenpa Rabjampa (1308-1364, possibly 1369). He systematized the Seminal Heart teachings[24] and other collections of texts that were circulating at the time in Tibet,[28] in the Seven Treasuries (mdzod bdun), the "Trilogy of Natural Freedom" (rang grol skor gsum), and the Trilogy of Natural Ease (ngal gso skor gsum).[3][24] Longchenpa refined the terminology and interpretations, and integrated the Seminal Heart teachings with broader Mahayana literature.[24]

Malcolm Smith notes that Longchenpa's Tshig don mdzod, the "Treasury of Subjects,"[web 2] was preceded by several other texts by other authors dealing with the same topics.[web 2] Smith mentions the 12th century text "The Eleven Subjects of The Great Perfection"[note 4] by Nyi 'bum. This itself was derived from the eighth and final chapter of the commentary to The String of Pearls Tantra.[web 2]

Nyi 'bum's "Eleven Subjects" is the basis for Longchenpa's "Treasury of Subjects" as well as Rigzin Godem's "The Aural Lineage of Vimalamitra"[note 5][web 2] from the Gongpa Zangthal.[web 2]

According to Smith, Nyi 'bum's "Eleven Subjects" provided the outline upon which Longchenpa's "Treasury of Subjects" was based, using the general sequence of citations, and even copying or reworking entire passages.[web 2] According to Smith, Nyi 'bum's "Eleven Subjects" was transmitted in a close circle of disciples, with very little outside contact, whereas Longchenpa's "Treasury of Subjects" contains responses to 14th century scholastic objections to Dzogchen.[web 2]

Later termas[edit]

In subsequent centuries more additions followed, including the "Profound Dharma of Self-Liberation through the Intention of the Peaceful and Wrathful Ones"[29] (kar-gling zhi-khro)[note 6] by Karma Lingpa,[30] (1326–1386), popularly known as "Karma Lingpa's Peaceful and Wrathful Ones",[29] which includes the two texts of the bar-do thos-grol, the "Tibetan Book of the Dead".[31][note 7]

Other important termas are "The Penetrating Wisdom" (dgongs pa zang thal), revealed by Rinzin Gödem (rig 'dzin rgod ldem, 1337-1409);[24] and "The Nucleus of Ati's Profound Meaning" (rDzogs pa chen po a ti zab don snying po) by Terdak Lingpa (gter bdag gling pa, 1646-1714).[24]

Particularly influential of these later revelations are the works of Jigme Lingpa (1730–1798).[24] His Longchen Nyingthig (klong chen snying thig), "The Heart-essence of the Vast Expanse"[33] or "The Seminal Heart of the Great Matrix",[24] is a hidden teaching from Padmasambhava which was revealed by Jigme Lingpa.[3][24] The Longchen Nyingthig is said to be the essence of the Vima Nyingthig and Khandro Nyingthig, the "Early Nyingthig,",[22] and has become known as the "later Nyingthig".[22] It is one of the most widely practiced teachings in the Nyingmapa school.[34] Patrul Rinpoche (1808–1887) wrote down Jigme Lingpa's pre-liminary practices into a book called The Words of My Perfect Teacher.[35]

In subsequent centuries more additions followed, including the "Profound Dharma of Self-Liberation through the Intention of the Peaceful and Wrathful Ones"[29] (kar-gling zhi-khro)[note 6] by Karma Lingpa,[30] (1326–1386), popularly known as "Karma Lingpa's Peaceful and Wrathful Ones",[29] which includes the two texts of the bar-do thos-grol, the "Tibetan Book of the Dead".[31][note 7]

Other important termas are "The Penetrating Wisdom" (dgongs pa zang thal), revealed by Rinzin Gödem (rig 'dzin rgod ldem, 1337-1409);[24] and "The Nucleus of Ati's Profound Meaning" (rDzogs pa chen po a ti zab don snying po) by Terdak Lingpa (gter bdag gling pa, 1646-1714).[24]

Particularly influential of these later revelations are the works of Jigme Lingpa (1730–1798).[24] His Longchen Nyingthig (klong chen snying thig), "The Heart-essence of the Vast Expanse"[33] or "The Seminal Heart of the Great Matrix",[24] is a hidden teaching from Padmasambhava which was revealed by Jigme Lingpa.[3][24] The Longchen Nyingthig is said to be the essence of the Vima Nyingthig and Khandro Nyingthig, the "Early Nyingthig,",[22] and has become known as the "later Nyingthig".[22] It is one of the most widely practiced teachings in the Nyingmapa school.[34] Patrul Rinpoche (1808–1887) wrote down Jigme Lingpa's pre-liminary practices into a book called The Words of My Perfect Teacher.[35]

Modern times[edit]

In the early 20th century the first publications on Tibetan Buddhism appeared in the west. An early publication on Dzogchen was the so-called "Tibetan Book of the Dead," edited by W.Y. Evans-Wentz, which became highly popular, but contains many mistakes in translation and interpretation.[32] Dzogchen has been popularized in the western world by the Tibetan diaspora, starting with the exile of 1959. Well-known teachers include Sogyal Rinpoche and Namkhai Norbu. The 14th Dalai Lama is also a qualified Dzogchen teacher.[web 3]

Chögyam Trungpa coined the term Maha Ati for Dzogchen,[36] a master of the Kagyu and Nyingma lineages of Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism. He generally preferred to introduce Sanskrit rather than Tibetan terms to his students and felt "Maha Ati" was the closest equivalent for Dzogchen, although he acknowledged it was an unorthodox choice. The coinage does not follow the sandhi rules which would be rendered as mahāti. This serves as an indication of its pedigree as a calque.

In the early 20th century the first publications on Tibetan Buddhism appeared in the west. An early publication on Dzogchen was the so-called "Tibetan Book of the Dead," edited by W.Y. Evans-Wentz, which became highly popular, but contains many mistakes in translation and interpretation.[32] Dzogchen has been popularized in the western world by the Tibetan diaspora, starting with the exile of 1959. Well-known teachers include Sogyal Rinpoche and Namkhai Norbu. The 14th Dalai Lama is also a qualified Dzogchen teacher.[web 3]

Chögyam Trungpa coined the term Maha Ati for Dzogchen,[36] a master of the Kagyu and Nyingma lineages of Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism. He generally preferred to introduce Sanskrit rather than Tibetan terms to his students and felt "Maha Ati" was the closest equivalent for Dzogchen, although he acknowledged it was an unorthodox choice. The coinage does not follow the sandhi rules which would be rendered as mahāti. This serves as an indication of its pedigree as a calque.

Kagyu and Gelugpa[edit]

Dzogchen has also been taught and practiced in the Kagyu[note 8] lineage,[28] beginning with the Third Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje (1284–1339).[note 9]

Lozang Gyatso, 5th Dalai Lama (1617–1682), Thubten Gyatso, 13th Dalai Lama ( 1876–1933), and Tenzin Gyatso, 14th Dalai Lama (present), all Gelugpas, are also noted Dzogchen masters, although their adoption of the practice of Dzogchen has been a source of controversy among more conservative members of the Gelug tradition.[web 3]

Dzogchen has also been taught and practiced in the Kagyu[note 8] lineage,[28] beginning with the Third Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje (1284–1339).[note 9]

Lozang Gyatso, 5th Dalai Lama (1617–1682), Thubten Gyatso, 13th Dalai Lama ( 1876–1933), and Tenzin Gyatso, 14th Dalai Lama (present), all Gelugpas, are also noted Dzogchen masters, although their adoption of the practice of Dzogchen has been a source of controversy among more conservative members of the Gelug tradition.[web 3]

CONCEPTUAL BACKGROUND[EDIT]

Tibetan Buddhism developed five main schools. The Madhyamika philosophy obtained a central position in the Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya and Gelugpa schools. The Jonang school, which until recently was thought to be extinct, developed a different interpretation of ultimate truth. Dzogchen texts use unique terminology to describe the Dzogchen view. Some of these terms deal with the different elements and features of the mind. The generic term for consciousness is shes pa, and includes the six sense consciousnesses. Different forms of shes pa include ye shes (Jñāna, 'pristine consciousness') and shes rab (prajñā, wisdom).[38]According to Sam van Schaik, two significant terms used in Dzogchen literature is the Ground (gzhi) and Gnosis (rig pa), which represent the "ontological and gnoseological aspects of the nirvanic state" respectively.[39] Dzogchen literature also describes nirvana as the "expanse" (klong or dbyings) or the "true expanse" (chos dbyings, Sanskrit: Dharmadhatu). The term Dharmakayais also often associated with these terms in Dzogchen,[40] as explained by Tulku Urgyen:

According to Malcolm Smith, the Dzogchen view is also based on the Indian Buddhist Buddha-nature doctrine of the Tathāgatagarbha sūtras.[42] According to the 14th Dalai Lama the Ground is the Buddha-nature, the nature of mind which is emptiness.[43] According to Rinpoche Thrangu, Rangjung Dorje (1284–1339), the third Karmapa Lama (head of the Karma Kagyu) and Nyingma lineage holder, also stated that the Ground is Buddha-nature.[note 10] According to Rinpoche Thrangu, "whether one does Mahamudra or Dzogchen practice, buddha nature is the foundation from which both of these meditations develop."[45]

Tibetan Buddhism developed five main schools. The Madhyamika philosophy obtained a central position in the Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya and Gelugpa schools. The Jonang school, which until recently was thought to be extinct, developed a different interpretation of ultimate truth. Dzogchen texts use unique terminology to describe the Dzogchen view. Some of these terms deal with the different elements and features of the mind. The generic term for consciousness is shes pa, and includes the six sense consciousnesses. Different forms of shes pa include ye shes (Jñāna, 'pristine consciousness') and shes rab (prajñā, wisdom).[38]According to Sam van Schaik, two significant terms used in Dzogchen literature is the Ground (gzhi) and Gnosis (rig pa), which represent the "ontological and gnoseological aspects of the nirvanic state" respectively.[39] Dzogchen literature also describes nirvana as the "expanse" (klong or dbyings) or the "true expanse" (chos dbyings, Sanskrit: Dharmadhatu). The term Dharmakayais also often associated with these terms in Dzogchen,[40] as explained by Tulku Urgyen:

According to Malcolm Smith, the Dzogchen view is also based on the Indian Buddhist Buddha-nature doctrine of the Tathāgatagarbha sūtras.[42] According to the 14th Dalai Lama the Ground is the Buddha-nature, the nature of mind which is emptiness.[43] According to Rinpoche Thrangu, Rangjung Dorje (1284–1339), the third Karmapa Lama (head of the Karma Kagyu) and Nyingma lineage holder, also stated that the Ground is Buddha-nature.[note 10] According to Rinpoche Thrangu, "whether one does Mahamudra or Dzogchen practice, buddha nature is the foundation from which both of these meditations develop."[45]

Basis[edit]

A key concept in Dzogchen is the 'basis', 'ground' or 'primordial state' (Tibetan: gzhi, Sanskrit: sthana), also called the general ground (spyi gzhi) or the original ground (gdod ma'i gzhi). The basis is the original state "before realization produced buddhas and nonrealization produced sentient beings". It is atemporal and unchanging and yet it is "noetically potent", giving rise to mind, delusion and wisdom.[47]The basis is also associated with the term Dharmata.[48]

- Essence - purity, which refers to emptiness (shunyata, stong pa nyid)

- Nature - Natural perfection (lhun grub), also translated "spontaneous presence",[51] which also refers to luminosity or clarity (gsal).

- Compassion (karuṇā, thugs rje), the "immanent presence of the ground in all appearances".[52]

The text, "An Aspirational prayer for the Ground, Path and Result" defines the three aspects of the basis thus:[53]

-

- Because its essence is empty, it is free from the limit of eternalism

- Because its nature is luminous, it is free from the extreme of nihilism

- Because its compassion is unobstructed, it is the ground of the manifold manifestations

Moreover, the basis is associated with the primordial or original Buddhahood, also called Samantabhadra, which is said to be beyond time itself and hence Buddhahood is not something to be gained, but an act of recognizing what is already immanent in all sentient beings.[54] Likewise, this view of the basis stems from the Indian Buddha-nature theory.[55] Other terms used to describe the basis include unobstructed (ma 'gags pa), universal (kun khyab) and omnipresent.[56]

A key concept in Dzogchen is the 'basis', 'ground' or 'primordial state' (Tibetan: gzhi, Sanskrit: sthana), also called the general ground (spyi gzhi) or the original ground (gdod ma'i gzhi). The basis is the original state "before realization produced buddhas and nonrealization produced sentient beings". It is atemporal and unchanging and yet it is "noetically potent", giving rise to mind, delusion and wisdom.[47]The basis is also associated with the term Dharmata.[48]

- Essence - purity, which refers to emptiness (shunyata, stong pa nyid)

- Nature - Natural perfection (lhun grub), also translated "spontaneous presence",[51] which also refers to luminosity or clarity (gsal).

- Compassion (karuṇā, thugs rje), the "immanent presence of the ground in all appearances".[52]

The text, "An Aspirational prayer for the Ground, Path and Result" defines the three aspects of the basis thus:[53]

-

- Because its essence is empty, it is free from the limit of eternalism

- Because its nature is luminous, it is free from the extreme of nihilism

- Because its compassion is unobstructed, it is the ground of the manifold manifestations

Moreover, the basis is associated with the primordial or original Buddhahood, also called Samantabhadra, which is said to be beyond time itself and hence Buddhahood is not something to be gained, but an act of recognizing what is already immanent in all sentient beings.[54] Likewise, this view of the basis stems from the Indian Buddha-nature theory.[55] Other terms used to describe the basis include unobstructed (ma 'gags pa), universal (kun khyab) and omnipresent.[56]

Rigpa[edit]

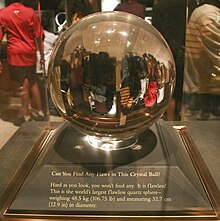

Rigpa (Sk: Vidya, "knowledge") is a central concept in Dzogchen which means "unconfused knowledge of the basis that is its own state".[57] It is "reflexively self-aware primordial wisdom,"[58] which is self-reflexively aware of itself as unbounded wholeness.[59][quote 2] The analogy given by Dzogchen masters is that one's true nature is like a mirror which reflects with complete openness, but is not affected by the reflections; or like a crystal ball that takes on the colour of the material on which it is placed without itself being changed. The knowledge that ensues from recognizing this mirror-like clarity (which cannot be found by searching nor identified)[60] is called rigpa.[61]

According to Alexander Berzin, there are three aspects of rigpa:[web 4]

- The essential nature of rigpa: primal purity (ka-dag). Rigpa is primordially without stains, both being self-void (rang-stong) and other-void (gzhan-stong);

- The influencing nature of rigpa: the manner in which rigpa influences others. Rigpa is responsiveness (thugs-rje, compassion). It responds effortlessly and spontaneously to others with compassion;

- The functional nature of rigpa: rigpa effortlessly and spontaneously establishes "appearances" (lhun-grub).

As Berzin notes, all of the good qualities (yon-tan) of a Buddha are already "are innate (lhan-skyes) to rigpa, which means that they arise simultaneously with each moment of rigpa, and primordial (gnyugs-ma), in the sense of having no beginning.[web 4]

Sam van Schaik translates rigpa as "gnosis" which he glosses as "a form of awareness aligned to the nirvanic state".[62] He notes that other definitions of rigpa include "free from elaborations" (srpos bral), "non conceptual" (rtog med) and "transcendent of the intellect" (blo 'das). It is also often paired with emptiness, as in the contraction rig stong (gnosis-emptiness).[63]

John W. Pettit notes that rigpa is seen as beyond affirmation and negation, acceptance and rejection, and therefore it is known as "natural" (ma bcos pa) and "effortless" (rtsol med) once recognized.[64] Because of this, Dzogchen is also known as the pinnacle and final destination of all paths.

Rigpa (Sk: Vidya, "knowledge") is a central concept in Dzogchen which means "unconfused knowledge of the basis that is its own state".[57] It is "reflexively self-aware primordial wisdom,"[58] which is self-reflexively aware of itself as unbounded wholeness.[59][quote 2] The analogy given by Dzogchen masters is that one's true nature is like a mirror which reflects with complete openness, but is not affected by the reflections; or like a crystal ball that takes on the colour of the material on which it is placed without itself being changed. The knowledge that ensues from recognizing this mirror-like clarity (which cannot be found by searching nor identified)[60] is called rigpa.[61]

According to Alexander Berzin, there are three aspects of rigpa:[web 4]

- The essential nature of rigpa: primal purity (ka-dag). Rigpa is primordially without stains, both being self-void (rang-stong) and other-void (gzhan-stong);

- The influencing nature of rigpa: the manner in which rigpa influences others. Rigpa is responsiveness (thugs-rje, compassion). It responds effortlessly and spontaneously to others with compassion;

- The functional nature of rigpa: rigpa effortlessly and spontaneously establishes "appearances" (lhun-grub).

As Berzin notes, all of the good qualities (yon-tan) of a Buddha are already "are innate (lhan-skyes) to rigpa, which means that they arise simultaneously with each moment of rigpa, and primordial (gnyugs-ma), in the sense of having no beginning.[web 4]

Sam van Schaik translates rigpa as "gnosis" which he glosses as "a form of awareness aligned to the nirvanic state".[62] He notes that other definitions of rigpa include "free from elaborations" (srpos bral), "non conceptual" (rtog med) and "transcendent of the intellect" (blo 'das). It is also often paired with emptiness, as in the contraction rig stong (gnosis-emptiness).[63]

John W. Pettit notes that rigpa is seen as beyond affirmation and negation, acceptance and rejection, and therefore it is known as "natural" (ma bcos pa) and "effortless" (rtsol med) once recognized.[64] Because of this, Dzogchen is also known as the pinnacle and final destination of all paths.

Ma Rigpa[edit]

Ma Rigpa (avidyā) is the opposite of rigpa or knowledge. Ma rigpa is ignorance or unawareness, the failure to recognize the nature of the basis. An important theme in Dzogchen texts is explaining how ignorance arises from the basis or Dharmata, which is associated with ye shes or 'pristine consciousness'.[65] Automatically arising unawareness (lhan-skyes ma-rigpa) exists because the basis is seen having a natural cognitive potentiality and luminosity (gdangs), which is the ground for samsara and nirvana. When consciousness fails to recognize that all phenomena arise as the creativity (rtsal) of the nature of mind and misses its own luminescence or does not "recognize its own face", sentient beings arise instead of Buddhas. As explained by Tulku Urgyen:

According to Vimalamitra's Illuminating Lamp, delusion arises because sentient beings "lapse towards external mentally apprehended objects". This external grasping is then said to produce sentient beings out of dependent origination.[67] This dualistic conceptualizing process which leads to samsara is termed manas as well as "awareness moving away from the ground".[68]

Ma Rigpa (avidyā) is the opposite of rigpa or knowledge. Ma rigpa is ignorance or unawareness, the failure to recognize the nature of the basis. An important theme in Dzogchen texts is explaining how ignorance arises from the basis or Dharmata, which is associated with ye shes or 'pristine consciousness'.[65] Automatically arising unawareness (lhan-skyes ma-rigpa) exists because the basis is seen having a natural cognitive potentiality and luminosity (gdangs), which is the ground for samsara and nirvana. When consciousness fails to recognize that all phenomena arise as the creativity (rtsal) of the nature of mind and misses its own luminescence or does not "recognize its own face", sentient beings arise instead of Buddhas. As explained by Tulku Urgyen:

According to Vimalamitra's Illuminating Lamp, delusion arises because sentient beings "lapse towards external mentally apprehended objects". This external grasping is then said to produce sentient beings out of dependent origination.[67] This dualistic conceptualizing process which leads to samsara is termed manas as well as "awareness moving away from the ground".[68]

Immanence and Distinction[edit]

According to Sam van Schaik, there is a certain tension in Dzogchen thought (as in other forms of Buddhism) between the idea that samsara and nirvana are immanent within each other and yet are still different. In texts such as the Longchen Nyingtig for example, the basis and rigpa are presented as being "intrinsically innate to the individual mind".[70] The Great Perfection Tantra of the Expanse of Samantabhadra’s Wisdom states:

Likewise, Longchenpa (12th century), writes in his Illuminating Sunlight:

This lack of difference between these two states, their non-dual (advaya) nature, corresponds with the idea that change from one to another doesn't happen due to an ordinary process of causation but is an instantaneous and perfect 'self-recognition' (rang ngo sprod) of what is already innately (lhan-skyes) there.[73] According to John W. Pettit, this idea has its roots in Indian texts such as Nagarjuna's Mulamadhyamakakarika, which states that samsara and nirvana are not separate and that there is no difference between the "doer", the "going" and the "going to" (i.e. the ground, path and fruit).[74]

In spite of this emphasis on immanence, Dzogchen texts do indicate a subtle difference between terms associated with delusion (kun gzhi or alaya, sems or mind) and terms associated with full enlightenment (dharmakaya and rigpa).[75] The Alaya and Ālayavijñāna are associated with karmic imprints (vasana) of the mind and with mental afflictions (klesa). The "alaya for habits" is the basis (gzhi) along with ignorance (marigpa) which includes all sorts of obscuring habits and grasping tendencies.[web 4]

According to Sam van Schaik, there is a certain tension in Dzogchen thought (as in other forms of Buddhism) between the idea that samsara and nirvana are immanent within each other and yet are still different. In texts such as the Longchen Nyingtig for example, the basis and rigpa are presented as being "intrinsically innate to the individual mind".[70] The Great Perfection Tantra of the Expanse of Samantabhadra’s Wisdom states:

Likewise, Longchenpa (12th century), writes in his Illuminating Sunlight:

This lack of difference between these two states, their non-dual (advaya) nature, corresponds with the idea that change from one to another doesn't happen due to an ordinary process of causation but is an instantaneous and perfect 'self-recognition' (rang ngo sprod) of what is already innately (lhan-skyes) there.[73] According to John W. Pettit, this idea has its roots in Indian texts such as Nagarjuna's Mulamadhyamakakarika, which states that samsara and nirvana are not separate and that there is no difference between the "doer", the "going" and the "going to" (i.e. the ground, path and fruit).[74]

In spite of this emphasis on immanence, Dzogchen texts do indicate a subtle difference between terms associated with delusion (kun gzhi or alaya, sems or mind) and terms associated with full enlightenment (dharmakaya and rigpa).[75] The Alaya and Ālayavijñāna are associated with karmic imprints (vasana) of the mind and with mental afflictions (klesa). The "alaya for habits" is the basis (gzhi) along with ignorance (marigpa) which includes all sorts of obscuring habits and grasping tendencies.[web 4]

Harmonisation with Madhyamaka[edit]

Koppl notes that although later Nyingma authors such as Mipham attempted to harmonize the view of Dzogchen with Madhyamaka, the earlier Nyingma author Rongzom Chokyi Zangpo did not.[77][quote 3] Rongzom held that the views of sutra such as Madhyamaka were inferior to that of tantra.[78][quote 4] In contrast, the 14th Dalai Lama, in his book Dzogchen, [79] concludes that Madhyamaka and Dzogchen come down to the same point. The view of reality obtained through Madhyamaka philosophy and the Dzogchen view of Rigpa can be regarded as identical. With regard to the practice in these traditions, however, at the initial stages there do seem certain differences in practice and emphasis.

Koppl notes that although later Nyingma authors such as Mipham attempted to harmonize the view of Dzogchen with Madhyamaka, the earlier Nyingma author Rongzom Chokyi Zangpo did not.[77][quote 3] Rongzom held that the views of sutra such as Madhyamaka were inferior to that of tantra.[78][quote 4] In contrast, the 14th Dalai Lama, in his book Dzogchen, [79] concludes that Madhyamaka and Dzogchen come down to the same point. The view of reality obtained through Madhyamaka philosophy and the Dzogchen view of Rigpa can be regarded as identical. With regard to the practice in these traditions, however, at the initial stages there do seem certain differences in practice and emphasis.

TEACHINGS AND PRACTICE[EDIT]

Dzogchen is a secret teaching emphasizing the rigpa view. It is a secret from those who are incapable of receiving it. The student can properly receive it with direct in-person realization under a guru's instruction. It is accessible to all; however, it is generally considered an advanced practice because safety from generating an incorrect view necessitates preliminary practices with a teacher's empowerment. [80]

Dzogchen teachings emphasize naturalness, spontaneity and simplicity.[9] Although Dzogchen is portrayed as being distinct from tantra, it has incorporated many concepts and practices from tantric Buddhism.[9] It embraces a widely varied array of traditions, that range from a systematic rejection of all tantric practices, to a full incorporation of tantric practices.[9]

Dzogchen is a secret teaching emphasizing the rigpa view. It is a secret from those who are incapable of receiving it. The student can properly receive it with direct in-person realization under a guru's instruction. It is accessible to all; however, it is generally considered an advanced practice because safety from generating an incorrect view necessitates preliminary practices with a teacher's empowerment. [80]

Dzogchen teachings emphasize naturalness, spontaneity and simplicity.[9] Although Dzogchen is portrayed as being distinct from tantra, it has incorporated many concepts and practices from tantric Buddhism.[9] It embraces a widely varied array of traditions, that range from a systematic rejection of all tantric practices, to a full incorporation of tantric practices.[9]

Three principles[edit]

The "Seminal Heart of Vimalamitra" epitomized the Dzogchen teaching in three principles, known as the Three Statements of Garab Dorje (Tsik Sum Né Dek). They give in short the development a student has to undergo:

- Direct introduction to one's own nature (Tib. ngo rang thog tu sprod pa), namely rigpa;

- Not remaining in doubt concerning this unique state (Tib. thag gcig thog tu bcad pa);

- Continuing to remain in this state (Tib. gdeng grol thog tu bca' pa).

In subsequent centuries these teachings were expanded, most notably in the Longchen Nyingthig by Jigme Lingpa (1730-1798).[3] His systematisation is the most widely used Dzogchen-teaching nowadays.[3]

The "Seminal Heart of Vimalamitra" epitomized the Dzogchen teaching in three principles, known as the Three Statements of Garab Dorje (Tsik Sum Né Dek). They give in short the development a student has to undergo:

- Direct introduction to one's own nature (Tib. ngo rang thog tu sprod pa), namely rigpa;

- Not remaining in doubt concerning this unique state (Tib. thag gcig thog tu bcad pa);

- Continuing to remain in this state (Tib. gdeng grol thog tu bca' pa).

In subsequent centuries these teachings were expanded, most notably in the Longchen Nyingthig by Jigme Lingpa (1730-1798).[3] His systematisation is the most widely used Dzogchen-teaching nowadays.[3]

Structure of practice[edit]

Anthology of practices[edit]

The dzogchen teachings consist of vast anthologies of practices presented as preliminary and auxiliary contemplative techniques, including standard Buddhist meditation techniques and tantra practices which have been integrated into Dzogchen.[81]

Longchenpa, in "Finding Comfort and Ease in Meditation" (bsam gtan ngal gso), the second text of the Trilogy of Natural Ease(ngal gso skor gsum),[82] and its auto-commentary the Shing rta rnam dag,[83] uses the standard triad of meditative experiences (nyams) to structure the text and the practices: bliss (bde ba), radiance/clarity (gsal ba), and non-conceptuality (mi rtog pa).[82]This triad is also presented as preliminaries, main practice, and concluding phase.[83] The preliminaries are further divided into:

- the general preliminaries on impermanence and renunciation of cyclic existence, which corresponds to the Therevada;

- the special preliminaries on compassion and the engendering of compassionate motivation, which corresponds with the Mahayana;

- the supreme preliminaries, consisting of the generation phase, perfection phase and Guru yoga.[83]

The dzogchen teachings consist of vast anthologies of practices presented as preliminary and auxiliary contemplative techniques, including standard Buddhist meditation techniques and tantra practices which have been integrated into Dzogchen.[81]

Longchenpa, in "Finding Comfort and Ease in Meditation" (bsam gtan ngal gso), the second text of the Trilogy of Natural Ease(ngal gso skor gsum),[82] and its auto-commentary the Shing rta rnam dag,[83] uses the standard triad of meditative experiences (nyams) to structure the text and the practices: bliss (bde ba), radiance/clarity (gsal ba), and non-conceptuality (mi rtog pa).[82]This triad is also presented as preliminaries, main practice, and concluding phase.[83] The preliminaries are further divided into:

- the general preliminaries on impermanence and renunciation of cyclic existence, which corresponds to the Therevada;

- the special preliminaries on compassion and the engendering of compassionate motivation, which corresponds with the Mahayana;

- the supreme preliminaries, consisting of the generation phase, perfection phase and Guru yoga.[83]

General overview[edit]

A general overview gives the following:

- Preliminary practices:

- Great Perfection practice:

- Further empowerment: receiving an empowerment (dbang, initiation) and keeping the vows conferred at that time. This activates our Buddha-mind, by consciously generating a state of mind that is accompanied by understanding;

- Supreme preliminary practices: Jigme Lingpa's ru shan and sbyong ba; practice of the three samadhis;[note 11]

- Main practice, which consists of:[web 4][quote 5]

- Concluding phase

A general overview gives the following:

- Preliminary practices:

- Great Perfection practice:

- Further empowerment: receiving an empowerment (dbang, initiation) and keeping the vows conferred at that time. This activates our Buddha-mind, by consciously generating a state of mind that is accompanied by understanding;

- Supreme preliminary practices: Jigme Lingpa's ru shan and sbyong ba; practice of the three samadhis;[note 11]

- Main practice, which consists of:[web 4][quote 5]

- Concluding phase

Preliminary practices[edit]

Initial empowerment[edit]

According to Tsoknyi Rinpoche, before one starts with the Dzogchen-practices empowerment is necessary. This plants the "seeds of realization" within the present body, speech and mind.[87] Empowerment "invests us with the ability to be liberated into the already present ground."[91] The practices bring the seeds to maturation, resulting in the qualities of enlightened body, speech and mind.[92]

According to Tsoknyi Rinpoche, before one starts with the Dzogchen-practices empowerment is necessary. This plants the "seeds of realization" within the present body, speech and mind.[87] Empowerment "invests us with the ability to be liberated into the already present ground."[91] The practices bring the seeds to maturation, resulting in the qualities of enlightened body, speech and mind.[92]

General or outer preliminaries[edit]

The outer preliminaries are as follows:[web 4]

- appreciating our precious human rebirths;

- contemplating death and impermanence;

- contemplating the faults of samsara;

- contemplating karmic cause and effect and the possibility of gaining liberation from it;

- contemplating the benefits of liberation;

- building and maintaining a good relation with a spiritual teacher;

The outer preliminaries are as follows:[web 4]

- appreciating our precious human rebirths;

- contemplating death and impermanence;

- contemplating the faults of samsara;

- contemplating karmic cause and effect and the possibility of gaining liberation from it;

- contemplating the benefits of liberation;

- building and maintaining a good relation with a spiritual teacher;

Special or inner preliminaries[edit]

The inner preliminaries are as follows:[web 4]

- taking refuge;

- cultivating bodhichitta and the "far-reaching attitudes" (Tib. phar-byin, Skt. paramita);

- practicing Vajrasattva recitation, for purification of the gross obstacles;

- practicing mandala offerings, in which we develop generosity and strengthen our enlightenment-building network of positive force;

- making kusali offerings of chöd, in which we imagine cutting up and giving away our ordinary bodies;

- practicing Guru Yoga, in which we recognize and focus on Buddha-nature in our spiritual mentors and in ourselves;

The inner preliminaries are as follows:[web 4]

- taking refuge;

- cultivating bodhichitta and the "far-reaching attitudes" (Tib. phar-byin, Skt. paramita);

- practicing Vajrasattva recitation, for purification of the gross obstacles;

- practicing mandala offerings, in which we develop generosity and strengthen our enlightenment-building network of positive force;

- making kusali offerings of chöd, in which we imagine cutting up and giving away our ordinary bodies;

- practicing Guru Yoga, in which we recognize and focus on Buddha-nature in our spiritual mentors and in ourselves;

Great perfection practices[edit]

Empowerment[edit]

According to Berzin, receiving empowerment (dbang, initiation) and keeping the vows conferred at that time is a necessary step to move on to the main practice. This activates our Buddha-mind, by consciously generating a state of mind that is accompanied by understanding. Alexander Berzin further notes:[web 4]

- "In Gelug, the conscious experience is some level of blissful awareness of voidness."

- "In the non-Gelug systems, it is focus on Buddha-nature in our tantric masters and in us, with some level of understanding of Buddha-nature."

- "In dzogchen, it is focus specifically on the basis three aspects of rigpa as Buddha-nature factors in our tantric masters and in us."

According to Berzin, receiving empowerment (dbang, initiation) and keeping the vows conferred at that time is a necessary step to move on to the main practice. This activates our Buddha-mind, by consciously generating a state of mind that is accompanied by understanding. Alexander Berzin further notes:[web 4]

- "In Gelug, the conscious experience is some level of blissful awareness of voidness."

- "In the non-Gelug systems, it is focus on Buddha-nature in our tantric masters and in us, with some level of understanding of Buddha-nature."

- "In dzogchen, it is focus specifically on the basis three aspects of rigpa as Buddha-nature factors in our tantric masters and in us."

Supreme preliminary practices[edit]

With the influence of tantra, and the systematisations of Longchenpa, the main Dzogchen practices came to be preceded by preliminary (meditative) practices.[93]

In the text "Finding Comfort and Ease in the Nature of Mind" (sems nyid ngal gso), which is part of the Trilogy of Natural Ease (ngal gso skor gsum), Longchenpa arranges 141 contemplative practices, split into three sections: exoteric Buddhism (92), tantra (92), and the Great Perfection (27).[94] Most of these practices are "technique-free."[82]The typical Buddhist meditations are relegated to the preliminary phase, while the main meditative practices are typical "direct" approaches.[95]

Longchenpa includes the perfection phase techniques of channels, winds and nuclei into the main and concluding phases.[96] The "concluding phase" includes discussions of new contemplative techniques, which aid the practice of the main phase.[97]

The Great Perfection practices as described by Jigme Lingpa consist of preliminary practices, specific for the Great Perfection practice, and the main practice.[98]

With the influence of tantra, and the systematisations of Longchenpa, the main Dzogchen practices came to be preceded by preliminary (meditative) practices.[93]

In the text "Finding Comfort and Ease in the Nature of Mind" (sems nyid ngal gso), which is part of the Trilogy of Natural Ease (ngal gso skor gsum), Longchenpa arranges 141 contemplative practices, split into three sections: exoteric Buddhism (92), tantra (92), and the Great Perfection (27).[94] Most of these practices are "technique-free."[82]The typical Buddhist meditations are relegated to the preliminary phase, while the main meditative practices are typical "direct" approaches.[95]

Longchenpa includes the perfection phase techniques of channels, winds and nuclei into the main and concluding phases.[96] The "concluding phase" includes discussions of new contemplative techniques, which aid the practice of the main phase.[97]

The Great Perfection practices as described by Jigme Lingpa consist of preliminary practices, specific for the Great Perfection practice, and the main practice.[98]

Jigme Lingpa – ru shan and sbyong ba[edit]

Jigme Lingpa mentions two kinds of preliminary practices, 'khor 'das ru shan dbye ba,[note 12] "making a gap between samsara and nirvana,"[99][86] and sbyong ba.[99]

Ru shan is a series of visualisation and recitation exercises,[99] derived from the Seminal Heart tradition.[95] The name reflects the dualism of the distinctions between mind and insight, ālaya and dharmakāya.[99] Longchenpa places this practice in the "enhancement" (bogs dbyung) section of his concluding phase. It describes a practice "involving going to a solitary spot and acting out whatever comes to your mind."[95][note 13][quote 6]

Sbyong ba is a variety of teachings for training (sbyong ba) the body, speech and mind. The training of the body entails instructions for physical posture. The training of speech mainly entails recitation, especially of the syllable hūm. The training of the mind is a Madhyamaka-like analysis of the concept of the mind, to make clear that mind cannot arise from anywhere, reside anywhere,or go anywhere. They are in effect an establishment of emptiness by means of the intellect.[100]

Jigme Lingpa mentions two kinds of preliminary practices, 'khor 'das ru shan dbye ba,[note 12] "making a gap between samsara and nirvana,"[99][86] and sbyong ba.[99]

Ru shan is a series of visualisation and recitation exercises,[99] derived from the Seminal Heart tradition.[95] The name reflects the dualism of the distinctions between mind and insight, ālaya and dharmakāya.[99] Longchenpa places this practice in the "enhancement" (bogs dbyung) section of his concluding phase. It describes a practice "involving going to a solitary spot and acting out whatever comes to your mind."[95][note 13][quote 6]

Sbyong ba is a variety of teachings for training (sbyong ba) the body, speech and mind. The training of the body entails instructions for physical posture. The training of speech mainly entails recitation, especially of the syllable hūm. The training of the mind is a Madhyamaka-like analysis of the concept of the mind, to make clear that mind cannot arise from anywhere, reside anywhere,or go anywhere. They are in effect an establishment of emptiness by means of the intellect.[100]

Meditative practices[edit]

According to Alexander Berzin, after the preliminary practices follow meditative practices, in which the practitioners works with the three aspects of rigpa.[web 4][note 14]

The three samadhis (ting-nge-’dzin gsum) are practiced, in which the practitioners works, in the imagination, with the three aspects of rigpa:

- "Basis samadhi" on the authentic nature (gzhi de-bzhin-nyid-kyi ting-nge-’dzin, de-ting): the meditator is absorbed in an approximation of rigpa’s primal purity. It is a state of open receptiveness (klong), which is the basis for being able to help others as a Buddha;

- "Path samadhi illuminating everywhere" (lam kun-snang-ba’i ting-nge-’dzin, snang-ting): being moved by compassion, the meditator is absorbed in an approximation of rigpa’s responsiveness;

- "Resultant samadhi on the cause" (‘bras-bu-rgyu’i-ting-nge-’dzin, rgyu-ting): the meditator is absorbed in the visualization of a seed-syllable, which brings the result of actually helping limited beings.

According to Alexander Berzin, after the preliminary practices follow meditative practices, in which the practitioners works with the three aspects of rigpa.[web 4][note 14]

The three samadhis (ting-nge-’dzin gsum) are practiced, in which the practitioners works, in the imagination, with the three aspects of rigpa:

- "Basis samadhi" on the authentic nature (gzhi de-bzhin-nyid-kyi ting-nge-’dzin, de-ting): the meditator is absorbed in an approximation of rigpa’s primal purity. It is a state of open receptiveness (klong), which is the basis for being able to help others as a Buddha;

- "Path samadhi illuminating everywhere" (lam kun-snang-ba’i ting-nge-’dzin, snang-ting): being moved by compassion, the meditator is absorbed in an approximation of rigpa’s responsiveness;

- "Resultant samadhi on the cause" (‘bras-bu-rgyu’i-ting-nge-’dzin, rgyu-ting): the meditator is absorbed in the visualization of a seed-syllable, which brings the result of actually helping limited beings.

Semdzin[edit]

The Dzogchen meditation practices also include a series of exercises known as Semdzin (sems dzin),[101] which literally means "to hold the mind" or "to fix mind."[101] They include a whole range of methods, including fixation, breathing, and different body postures, all aiming to bring one into the state of contemplation.[102][note 15]

The Dzogchen meditation practices also include a series of exercises known as Semdzin (sems dzin),[101] which literally means "to hold the mind" or "to fix mind."[101] They include a whole range of methods, including fixation, breathing, and different body postures, all aiming to bring one into the state of contemplation.[102][note 15]

Main practice[edit]

Trekchö[edit]

The practice of Trekchö (khregs chod), "cutting through solidity",[88] reflects the earliest developments of Dzogchen, with its admonition against practice.[3][note 16] In this practice one first identifies, and then sustains recognition of, one's own innately pure, empty awareness.[105][106][quote 7] Students receive pointing-out instruction (sems khrid, ngos sprod) in which a teacher introduces the student to the nature of his or her mind.[3] According to Tsoknyi Rinpoche, these instructions are received after the preliminary practices, though there's also a tradition to give them before the preliminary practices.[109][quote 8][quote 9][note 17]

Jigme Lingpa divides the trekchö practice into ordinary and extraordinary instructions.[112] The ordinary section comprises the rejection of the all is mind – mind is empty approach, which is a conceptual establishment of emptiness.[112] Jigme Lingpa's extraordinary instructions give the instructions on the breakthrough proper, which consist of the setting out of the view (lta ba), the doubts and errors that may occur in practice, and some general instructions thematized as "the four ways of being at leisure" (cog bzhag).[112] The "setting out of the view" tries to point the reader toward a direct recognition of rigpa, insisting upon the immanence of rigpa, and dismissive of meditation and effort.).[113] Insight leads to nyamshag, "being present in the state of clarity and emptiness".[114]

The practice of Trekchö (khregs chod), "cutting through solidity",[88] reflects the earliest developments of Dzogchen, with its admonition against practice.[3][note 16] In this practice one first identifies, and then sustains recognition of, one's own innately pure, empty awareness.[105][106][quote 7] Students receive pointing-out instruction (sems khrid, ngos sprod) in which a teacher introduces the student to the nature of his or her mind.[3] According to Tsoknyi Rinpoche, these instructions are received after the preliminary practices, though there's also a tradition to give them before the preliminary practices.[109][quote 8][quote 9][note 17]

Jigme Lingpa divides the trekchö practice into ordinary and extraordinary instructions.[112] The ordinary section comprises the rejection of the all is mind – mind is empty approach, which is a conceptual establishment of emptiness.[112] Jigme Lingpa's extraordinary instructions give the instructions on the breakthrough proper, which consist of the setting out of the view (lta ba), the doubts and errors that may occur in practice, and some general instructions thematized as "the four ways of being at leisure" (cog bzhag).[112] The "setting out of the view" tries to point the reader toward a direct recognition of rigpa, insisting upon the immanence of rigpa, and dismissive of meditation and effort.).[113] Insight leads to nyamshag, "being present in the state of clarity and emptiness".[114]

Tögal[edit]

Tögal (thod rgal) means "spontaneous presence",[89][90] "direct crossing",[115] "direct crossing of spontaneous presence",[116] or "direct transcendence.[21] The literal meaning is "to proceed directly to the goal without having to go through intermediate steps."[117]

Tögal is also called "the practice of vision",[web 6] or "the practice of the Clear Light (od-gsal)".[web 6] It entails progressing through the Four Visions.[118] The practices engage the subtle body of psychic channels, winds and drops (rtsa rlung thig le).[3] The practices aim at generating a spontaneous flow of luminous, rainbow-colored images that gradually expand in extent and complexity.[24]

Tögal is an innovative practice,[24] and reflects the innovations of the Manngede cycles in Dzogchen, and the incorporation of complex tantric techniques and doctrines.[3]They are an adaptation of Tantric "perfection phase" techniques (rdzogs rim),[24] as outlined in the early-eleventh-century Indian Tantric Kalachakra cycle, "The Wheel of Time",[24] which was probably a direct inspiration for the Seminal Heart.[24]

Tögal (thod rgal) means "spontaneous presence",[89][90] "direct crossing",[115] "direct crossing of spontaneous presence",[116] or "direct transcendence.[21] The literal meaning is "to proceed directly to the goal without having to go through intermediate steps."[117]

Tögal is also called "the practice of vision",[web 6] or "the practice of the Clear Light (od-gsal)".[web 6] It entails progressing through the Four Visions.[118] The practices engage the subtle body of psychic channels, winds and drops (rtsa rlung thig le).[3] The practices aim at generating a spontaneous flow of luminous, rainbow-colored images that gradually expand in extent and complexity.[24]