Tara westover was raised by survivalist parents in the mountains of rural Idaho, and didn’t go to school. “Dad said public school was a ploy by the Government to lead children away from God,” she writes in her best-selling 2018 memoir, Educated. Still, she taught herself enough to attend college at Brigham Young University, and later earned a doctorate from Cambridge University. Today, she lives in New York City.

Westover recently spoke with Jeffrey Goldberg about cultural separation and mutual misunderstanding in America.

To hear more feature stories, see our full list or get the Audm iPhone app.

This interview has been shortened and edited for clarity.

Jeffrey Goldberg: You told me once that there is an “experience gap” in our national life—that we no longer share some underlying common experience as Americans.

Tara Westover: Yes, and the experience gap is fast becoming an empathy gap.

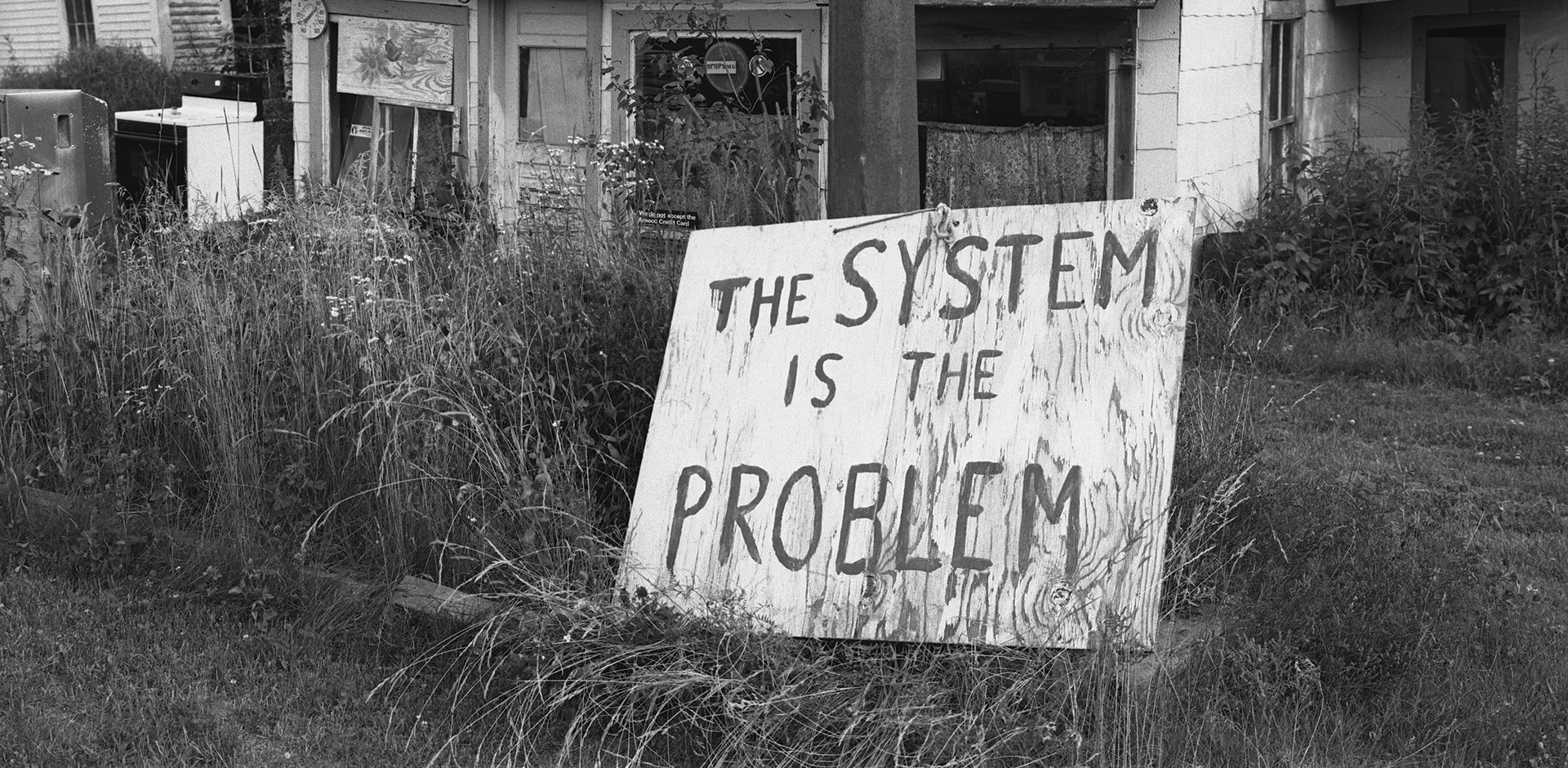

Westover: We have a shared history and shared interests as Americans, that’s true, but it’s also true that Democrats and Republicans increasingly live and work in different places. We have different experiences. As a general rule, I think we focus far too much on Donald Trump. We act like he’s the problem, but he’s not. He’s just a symptom—a sign of poor political hygiene.

Goldberg: Poor political hygiene?

Westover: Social media has flooded our consciousness with caricatures of each other. Human beings are reduced to data, and data nearly always underrepresent reality. The result is this great flattening of human life and human complexity. We think that because we know someone is pro-choice or pro-life, or that they drive a truck or a Prius, we know everything we need to know about them. Human detail gets lost in the algorithm. Thus humanity gives way to ideology.

Goldberg: So good political hygiene includes a respect for human complexity?

Westover: Our political system requires us to have a basic level of respect for each other, of empathy for each other. That loss of empathy is what I call a breaking of charity.

Goldberg: What does that mean?

Westover: It’s a term that’s associated with the Salem witch trials, and it refers to the moment when two members of a tribe disfellowship each other, and become two tribes. That, I think, is the biggest threat to our country, more than any single issue or politician. It’s the fact that the left and the right, the elite and the non-elite, the urban and the rural—however you want to slice it up—they no longer see themselves reflected in the other person. They no longer interpret each other as having charitable intent.

Westover: The fact that Democrats and Republicans now have a different experience of life in this country. Broadly speaking, the modern economy works well for cities and badly for the countryside. In recent years, growth has been hyper-concentrated in our cities, which are hubs of technology and finance. Meanwhile, the hinterlands, which rely on agriculture and manufacturing—what you might call the “old economy”—have sunk into a deep decline. There are places in the United States where the recession never ended. For them, it has been 2009 for 10 years. That does something to people, psychologically.

Goldberg: And that’s what is causing the current political divide?

Westover: That’s what I think. And everyone used to think that. When Trump first won the nomination, it was generally thought that his populism was fueled by economic disparities, but for some reason, after he was elected, that view went out of fashion. I don’t know why, because it is quite obviously the case—although to see it you need to think in terms of ecosystems, rather than individual incomes. Democratic strongholds are thriving. There’s this abundance of tech and professional jobs, and an educated population to fill them. Many Republican districts are experiencing negative growth, left behind by a changing economy. There is no place for them in this future we are making.

You can see this even at the state level. Take the 20 poorest states, by median household income, and you’ll see that 18 of them went for Trump. If you take the 10 richest states, nine went for Hillary Clinton. Our economic divide now tracks almost perfectly with our political divide. The 2016 election was about geospatial inequality. It was about the parts of the country that are suffering under technological change and globalization.

Prejudice is not new in this country. What is new is that, at the moment when we thought we had at last banished it to the fringe, here it is again, displayed openly in our public spaces. My own view is that economic distress activates prejudice. It makes it lethal. Of course, our country struggled with prejudice before Trump, but I don’t think that prejudice had been weaponized to the extent that it is now. Immigration and affirmative action were not the top issues on people’s minds. They probably weren’t even in the top three.

But in a climate of desperation and economic realignment, of uncertainty about the future, people become tribal. They become vulnerable to narratives that demonize those who are not like them. Most rural Americans don’t understand the vast technological and geopolitical shifts that are destroying their way of life. How could they? I don’t understand those shifts, and I’ve been trying pretty hard. It’s very easy for someone to come along and tell them that the problem is immigration. That’s what happened in 2016. Trump told a more convincing story about what was happening in America than the left did.

Goldberg: So who does the Democratic Party represent?

Goldberg: And those Democratic districts look very different from where you’re from?

Westover: Where I’m from is dying. It’s an entire ecosystem in decline. I was with my cousin recently, driving through the county seat where I grew up—a little town of about 5,000 people called Preston, Idaho. We were passing down the main street, and I saw that every single shop we’d gone to as kids was boarded up. But there was a brand-new funeral parlor, bringing the town’s total funeral parlors to two. That means the town now has one grocery store and two funeral parlors. My cousin turned to me and said, “You know what? It’s getting so the only thing there is to do around here is die.”

Goldberg: Do you think of where you grew up as parochial?

Westover: I used to think of Idaho as parochial, and I used to think of cities as sophisticated. And in many ways, I was right. You can get a better education in a city; you can learn more technical skills, and more about certain types of culture. But as I’ve grown older, I’ve come to believe that there are many ways a person can be parochial. Now I define parochial as only knowing people who are just like you—who have the same education that you have, the same political views, the same income. And by that definition, New York City is just about the most parochial place I’ve ever lived. I have become more parochial since I came here.

Goldberg: Do people in Idaho assume that now that you live in New York, you’ve really left Idaho in some important way?

Westover: They do assume that, and they are right. At some point, you have to acknowledge that you can’t embody your origins forever. At some point, you have to surrender your card. I’m more urbanite now than hayseed. I can’t change that, but I certainly feel some grief over it.

Goldberg: So you have not broken charity with your home state?

Westover: I try not to. And a lot of people on the left haven’t either. But from time to time you hear a strong tone of condescension emanating from our urban centers. You hear it in the way people talk about obesity rates in the rural United States, or about the lower number of college graduates from rural areas. These are serious problems that are hitting rural America specifically because of devastating shifts in our economic system, because of underinvestment in education, because people in these areas don’t have access to decent health care or sometimes to any health care at all. You look at where the holes are in Obamacare—they’re in rural areas. You look at where the opioid epidemic hit hard—it’s in rural areas. You look at educational outcomes for rural kids—they’re troubling, every report. These facts should be the foundation of our empathy, not of our contempt.

end quote from:

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/12/tara-westover-trump-rural-america/600916/

No comments:

Post a Comment