However, I don't think this will work in Ukraine for a variety of reasons.

begin quote

First Chechen War

People also ask

First Chechen War

| First Chechen War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Chechen-Russian conflict and post-Soviet conflicts | |||||||||

A Russian Mil Mi-8 helicopter brought down by Chechen fighters near the capital Grozny in 1994. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

Foreign volunteers: |

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

(+1500 mercenaries) | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

Other estimates: 14,000 soldiers killed or missing (CSMR estimate) 1,906[11]–3,000[12] missing | |||||||||

| 30,000–40,000 civilians killed (RFSSS data)[13] 80,000 civilians killed (Human rights groups estimate)[14] At least 161 civilians killed outside Chechnya[15] 500,000+ civilians displaced[16] | |||||||||

The First Chechen War,[17] also known as the First Chechen Campaign[a],[18][19][20] or First Russian-Chechen war was a rebellion by the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria against the Russian Federation, fought from December 1994 to August 1996. The first war was preceded by the Russian Intervention in Ichkeria, in which Russia tried to covertly overthrow the Ichkerian government. After the initial campaign of 1994–1995, culminating in the devastating Battle of Grozny, Russian federal forces attempted to seize control of the mountainous area of Chechnya, but faced heavy resistance from Chechen guerrillas and raids on the flatlands. Despite Russia's overwhelming advantages in firepower, manpower, weaponry, artillery, combat vehicles, airstrikes and air support, the resulting widespread demoralization of federal forces and the almost universal opposition of the Russian public to the conflict led Boris Yeltsin's government to declare a ceasefire with the Chechens in 1996, and finally a peace treaty in 1997.

The official figure for Russian military deaths was 5,732; most estimates put the number between 3,500 and 7,500, but some go as high as 14,000.[21] Although there are no accurate figures for the number of Chechen forces killed, various estimates put the number between approximately 3,000 to 17,391 dead or missing. Various figures estimate the number of civilian deaths at between 30,000 and 100,000 killed and possibly over 200,000 injured, while more than 500,000 people were displaced by the conflict, which left cities and villages across the republic in ruins.[22][16] The conflict led to a significant decrease of non-Chechen population due to violence and discrimination.[23][24][25]

Contents

- 1Origins

- 2Internal conflict in Chechnya and the Grozny–Moscow tensions

- 3Russian military intervention and initial stages

- 4Storming of Grozny

- 5Continued Russian offensive

- 6Spread of the war

- 7Continuation of the Russian offensive

- 8Third Battle of Grozny and the Khasavyurt Accord

- 9Aftermath

- 10Foreign policy implications

- 11See also

- 12Notes

- 13Further reading

- 14External links

Origins[edit]

Chechnya within Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union[edit]

Chechen resistance against Russian imperialism has its origins from 1785 during the time of Sheikh Mansur, the first imam (leader) of the Caucasian peoples. He united various North-Caucasian nations under his command in order to resist the Russian invasions and expansion.

Following long local resistance during the 1817–1864 Caucasian War, Imperial Russian forces defeated the Chechens and annexed their lands and deported thousands to the Middle East in the latter part of the 19th century. The Chechens' subsequent attempts at gaining independence after the 1917 fall of the Russian Empire failed, and in 1922 Chechnya became part of Soviet Russia and in December 1922 part of the newly formed Soviet Union (USSR). In 1936, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin established the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic.

In 1944, on the orders of NKVD chief Lavrentiy Beria, more than half a million Chechens, the Ingush and several other North Caucasian people were ethnically cleansed, and deported to Siberia and to Central Asia. The official pretext was punishment for collaboration with the invading German forces during the 1940–1944 insurgency in Chechnya,[26] despite many Chechens and Ingush being aligned to the Soviet Union and fighting against the Nazis and even receiving the highest military award in the Soviet Union (e.g. Khanpasha Nuradilov, Movlid Visaitov). In March 1944, the Soviet authorities abolished the Chechen-Ingush Republic. Eventually, Soviet first secretary Nikita Khrushchev granted the Vainakh (Chechen and Ingush) peoples the permission to return to their homeland and restored their republic in 1957.[citation needed]

Dissolution of the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation Treaty[edit]

Russia became an independent state after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991. The Russian Federation was widely accepted as the successor state to the USSR, but it lost a significant amount of its military and economic power. Ethnic Russians made up more than 80% of the population of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, but significant ethnic and religious differences posed a threat of political disintegration in some regions. In the Soviet period, some of Russia's approximately 100 nationalities were granted ethnic enclaves that had various formal federal rights attached. Relations of these entities with the federal government and demands for autonomy erupted into a major political issue in the early 1990s. Boris Yeltsin incorporated these demands into his 1990 election campaign by claiming that their resolution was a high priority.

There was an urgent need for a law to clearly define the powers of each federal subject. Such a law was passed on 31 March 1992, when Yeltsin and Ruslan Khasbulatov, then chairman of the Russian Supreme Soviet and an ethnic Chechen himself, signed the Federation Treaty bilaterally with 86 out of 88 federal subjects. In almost all cases, demands for greater autonomy or independence were satisfied by concessions of regional autonomy and tax privileges. The treaty outlined three basic types of federal subjects and the powers that were reserved for local and federal government. The only federal subjects that did not sign the treaty were Chechnya and Tatarstan. Eventually, in early 1994, Yeltsin signed a special political accord with Mintimer Shaeymiev, the president of Tatarstan, granting many of its demands for greater autonomy for the republic within Russia; thus, Chechnya remained the only federal subject that did not sign the treaty. Neither Yeltsin nor the Chechen government attempted any serious negotiations and the situation deteriorated into a full-scale conflict.

Chechen declaration of independence[edit]

Meanwhile, on 6 September 1991, militants of the All-National Congress of the Chechen People (NCChP) party, created by the former Soviet Air Force general Dzhokhar Dudayev, stormed a session of the Chechen-Ingush ASSR Supreme Soviet with the aim of asserting independence. The storming caused the death of the head of Grozny's branch of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Vitaly Kutsenko, who was defenestrated or fell while trying to escape. This effectively dissolved the government of the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Republic of the Soviet Union.[27][28][29]

The elections of president and parliament of Chechnya held on 27 October 1991. A day before, the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union published in local Chechen press that the elections were illegal. With a turnout of 72%, 90.1% voted for Dudayev.[30]

Dudayev won overwhelming popular support[citation needed] (as evidenced by the later presidential elections with high turnout and a clear Dudayev victory) to oust the interim administration that was supported by the central government. He was made president and declared independence from the Soviet Union.

In November 1991, Yeltsin dispatched Internal Troops to Grozny, but they were forced to withdraw when Dudayev's forces surrounded them at the airport. After Chechnya made its initial declaration of sovereignty, the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Republic split in two in June 1992 amidst the Ingush armed conflict against another Russian republic, North Ossetia. The newly created republic of Ingushetia then joined the Russian Federation, while Chechnya declared full independence from Moscow in 1993 as the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria (ChRI).

Internal conflict in Chechnya and the Grozny–Moscow tensions[edit]

From 1991 to 1994, tens of thousands of people of non-Chechen ethnicity left the republic amidst reports of violence and discrimination against the non-Chechen population (mostly Russians, Ukrainians and Armenians).[23][24][25] During the undeclared Chechen civil war, factions both sympathetic and opposed to Dudayev fought for power, sometimes in pitched battles with the use of heavy weapons. In March 1992, the opposition attempted a coup d'état, but their attempt was crushed by force. A month later, Dudayev introduced direct presidential rule, and in June 1993, dissolved the Chechen parliament to avoid a referendum on a vote of non-confidence. In late October 1992, Russian forces dispatched to the zone of the Ossetian-Ingush conflict were ordered to move to the Chechen border; Dudayev, who perceived this as "an act of aggression against the Chechen Republic", declared a state of emergency and threatened general mobilization if the Russian troops did not withdraw from the Chechen border. To prevent the invasion of Chechnya, he did not provoke the Russian troops.

After staging another coup d'état attempt in December 1993, the opposition organized themselves into the Provisional Council of the Chechen Republic as a potential alternative government for Chechnya, calling on Moscow for assistance. In August 1994, the coalition of the opposition factions based in north Chechnya launched a large-scale armed campaign to remove Dudayev's government.

However, the issue of contention was not independence from Russia: even the opposition stated there was no alternative to an international boundary separating Chechnya from Russia. In 1992, Russian newspaper Moscow News noted that, just like most of the other seceding republics, other than Tatarstan, ethnic Chechens universally supported the establishment of an independent Chechen state[31] and, in 1995, during the heat of the First Chechen War, Khalid Delmayev, an anti-Dudayev belonging to an Ichkerian liberal coalition, stated that "Chechnya's statehood may be postponed... but cannot be avoided".[32] Opposition to Dudayev came mainly due to his domestic policy and personality: he once notoriously claimed that Russia intended to destabilize his nation by "artificially creating earthquakes" in Georgia and Armenia. This did not go off well with most Chechens, who came to view him as a national embarrassment at times (if still a patriot at others), but it did not, by any means, dismantle the determination for independence, as most Western commentators note.[33][original research?]

Moscow clandestinely supplied separatist forces with financial support, military equipment and mercenaries. Russia also suspended all civilian flights to Grozny while the aviation and border troops set up a military blockade of the republic, and eventually unmarked Russian aircraft began combat operations over Chechnya. The opposition forces, who were joined by Russian troops, launched a clandestine but badly organized assault on Grozny in mid-October 1994, followed by a second, larger attack on 26–27 November 1994. Despite Russian support, both attempts were unsuccessful. Dudayev loyalists succeeded in capturing some 20 Russian Army regulars and about 50 other Russian citizens who were clandestinely hired by the Russian FSK state security organization to fight for the Provisional Council forces.[34] On 29 November, President Boris Yeltsin issued an ultimatum to all warring factions in Chechnya ordering them to disarm and surrender. When the government in Grozny refused, Yeltsin ordered the Russian army to "restore constitutional order" by force.

Beginning on 1 December, Russian forces openly carried out heavy aerial bombardments of Chechnya. On 11 December 1994, five days after Dudayev and Russian Minister of Defense Gen. Pavel Grachev of Russia had agreed to "avoid the further use of force", Russian forces entered the republic in order to "establish constitutional order in Chechnya and to preserve the territorial integrity of Russia." Grachev boasted he could topple Dudayev in a couple of hours with a single airborne regiment, and proclaimed that it will be "a bloodless blitzkrieg, that would not last any longer than 20 December.".

Russian military intervention and initial stages[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

On 11 December 1994, Russian forces launched a three-pronged ground attack towards Grozny. The main attack was temporarily halted by the deputy commander of the Russian Ground Forces, General Eduard Vorobyov [Wikidata], who then resigned in protest, stating that it is "a crime" to "send the army against its own people."[35] Many in the Russian military and government opposed the war as well. Yeltsin's adviser on nationality affairs, Emil Pain, and Russia's Deputy Minister of Defense General Boris Gromov (esteemed commander of the Afghan War), also resigned in protest of the invasion ("It will be a bloodbath, another Afghanistan", Gromov said on television), as did General Boris Poliakov. More than 800 professional soldiers and officers refused to take part in the operation; of these, 83 were convicted by military courts and the rest were discharged. Later General Lev Rokhlin also refused to be decorated as a Hero of the Russian Federation for his part in the war.

The Chechen Air Force (as well as the republic's civilian aircraft fleet) was completely destroyed in the air strikes that occurred on the very first few hours of the war, while around 500 people took advantage of the mid-December amnesty declared by Yeltsin for members of Dzhokhar Dudayev's armed groups. Nevertheless, Boris Yeltsin's cabinet's expectations of a quick surgical strike, quickly followed by Chechen capitulation and regime change, were misguided. Russia found itself in a quagmire almost instantly. The morale of the Russian troops, poorly prepared and not understanding why and even where they were being sent, was low from the beginning. Some Russian units resisted the order to advance, and in some cases, the troops sabotaged their own equipment. In Ingushetia, civilian protesters stopped the western column and set 30 military vehicles on fire, while about 70 conscripts deserted their units. Advance of the northern column was halted by the unexpected Chechen resistance at Dolinskoye and the Russian forces suffered their first serious losses.[35] Deeper in Chechnya, a group of 50 Russian paratroopers surrendered to the local Chechen militia, having been abandoned after being deployed by helicopters behind enemy lines to capture a Chechen weapons cache.[36]

Yeltsin ordered the Russian Army to show restraint, but it was neither prepared nor trained for this. Civilian losses quickly mounted, alienating the Chechen population and raising the hostility that they showed towards the Russian forces, even among those who initially supported the Russians' attempts to unseat Dudayev. Other problems occurred as Yeltsin sent in freshly trained conscripts from neighboring regions rather than regular soldiers. Highly mobile units of Chechen fighters inflicted severe losses on the ill-prepared and demoralized Russian troops. Although the Russian military command ordered to only attack designated targets, due to the lack of training and experience of Russian forces, they attacked random positions instead, turning into carpet bombing and indiscriminate barrages of rocket artillery, and causing enormous casualties among the Chechen and Russian civilian population.[37] On 29 December, in a rare instance of a Russian outright victory, the Russian airborne forces seized the military airfield next to Grozny and repelled a Chechen armoured counter-attack in the Battle of Khankala; the next objective was the city itself. With the Russians closing in on the capital, the Chechens began to hastily set up defensive fighting positions and grouped their forces in the city.

Storming of Grozny[edit]

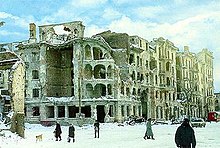

When the Russians besieged the Chechen capital, thousands of civilians died from a week-long series of air raids and artillery bombardments in the heaviest bombing campaign in Europe since the destruction of Dresden.[38] The initial assault on New Year's Eve 1994 ended in a major Russian defeat, resulting in heavy casualties and at first nearly a complete breakdown of morale in the Russian forces. The disaster claimed the lives of an estimated 1,000 to 2,000 Russian soldiers, mostly barely trained and disoriented conscripts; the heaviest losses were inflicted on the 131st 'Maikop' Motor Rifle Brigade, which was completely destroyed in the fighting near the central railway station.[35] Despite the early Chechen defeat of the New Year's assault and the many further casualties that the Russians had sustained, Grozny was eventually conquered by Russian forces amidst bitter urban warfare. After armored assaults failed, the Russian military set out to take the city using air power and artillery. At the same time, the Russian military accused the Chechen fighters of using civilians as human shields by preventing them from leaving the capital as it came under continued bombardment.[39] On 7 January 1995, Russian Major-General Viktor Vorobyov was killed by mortar fire, becoming the first on a long list of Russian generals to be killed in Chechnya. On 19 January, despite heavy casualties, Russian forces seized the ruins of the Chechen presidential palace, which had been heavily contested for more than three weeks as the Chechens finally abandoned their positions in the destroyed downtown area. The battle for the southern part of the city continued until the official end on 6 March 1995.

By the estimates of Yeltsin's human rights adviser Sergei Kovalev, about 27,000 civilians died in the first five weeks of fighting. Russian historian and general Dmitri Volkogonov said the Russian military's bombardment of Grozny killed around 35,000 civilians, including 5,000 children, and that the vast majority of those killed were ethnic Russians. While military casualties are not known, the Russian side admitted to having 2,000 soldiers killed or missing.[40] The bloodbath of Grozny shocked Russia and the outside world, causing severe criticism of the war. International monitors from the OSCE described the scenes as nothing short of an "unimaginable catastrophe", while former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev called the war a "disgraceful, bloody adventure" and German Chancellor Helmut Kohl called it "sheer madness".[41]

Continued Russian offensive[edit]

Following the fall of Grozny, the Russian government slowly but systematically expanded its control over the lowland areas and then into the mountains. In what was dubbed the worst massacre in the war, the OMON and other federal forces killed at least 103 civilians while seizing the border village of Samashki on 7 April (several hundred more were detained and beaten or otherwise tortured).[42] In the southern mountains, the Russians launched an offensive along the entire front on 15 April, advancing in large columns of 200–300 vehicles.[43] The ChRI forces defended the city of Argun, moving their military headquarters first to completely surrounded Shali, then shortly after to Serzhen-Yurt as they were forced into the mountains, and finally to Shamil Basayev's ancestral stronghold of Vedeno. Chechnya's second-largest city of Gudermes was surrendered without a fight, but the village of Shatoy was fought for and defended by the men of Ruslan Gelayev. Eventually, the Chechen command withdrew from the area of Vedeno to the Chechen opposition-aligned village of Dargo, and from there to Benoy.[44] According to an estimate cited in a United States Army analysis report, between January and June 1995, when the Russian forces conquered most of the republic in the conventional campaign, their losses in Chechnya were approximately 2,800 killed, 10,000 wounded and more than 500 missing or captured.[45] However, some Chechen fighters infiltrated already pacified places hiding in crowds of returning refugees.[46]

As the war continued, separatists resorted to mass-hostage takings, attempting to influence the Russian public and leadership. In June 1995, a group led by the maverick field commander Shamil Basayev took more than 1,500 people hostage in southern Russia in the Budyonnovsk hospital hostage crisis; about 120 Russian civilians died before a ceasefire was signed after negotiations between Basayev and the Russian Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin. The raid enforced a temporary stop in Russian military operations, giving the Chechens time to regroup during their greatest crisis and to prepare for the national militant campaign. The full-scale Russian attack led many of Dudayev's opponents to side with his forces and thousands of volunteers to swell the ranks of mobile militant units. Many others formed local self-defence militia units to defend their settlements in the case of federal offensive action, officially numbering 5,000–6,000 armed men in late 1995. Altogether, the ChRI forces fielded some 10,000–12,000 full-time and reserve fighters at a time, according to the Chechen command. According to a UN report, the Chechen separatist forces included a large number of child soldiers, some as young as 11 and including females.[47] As the territory controlled by them shrank, the separatists increasingly resorted to using classic guerrilla warfare tactics, such as setting booby traps and mining roads in enemy-held territory. The successful use of improvised explosive devices was particularly noteworthy; they also effectively exploited a combination of mines and ambushes.

In the fall of 1995, Gen. Anatoliy Romanov, the federal commander in Chechnya at the time, was critically injured and paralyzed in a bomb blast in Grozny. Suspicion of responsibility for the attack fell on rogue elements of the Russian military, as the attack destroyed hopes for a permanent ceasefire based on the developing trust between Gen. Romanov and the ChRI Chief of Staff Aslan Maskhadov, a former colonel in the Soviet Army;[48] in August, the two went to southern Chechnya in an effort to convince the local commanders to release Russian prisoners.[49] In February 1996, the federal and pro-Russian Chechen forces in Grozny opened fire on a massive pro-independence peace march which had involved tens of thousands of people, killing a number of demonstrators.[50] The ruins of the presidential palace, the symbol of Chechen independence, were then demolished two days later.

Human rights and war crimes[edit]

Human rights organizations accused Russian forces of engaging in indiscriminate and disproportionate use of force whenever encountering resistance, resulting in numerous civilian deaths (for example, according to Human Rights Watch, Russian artillery and rocket attacks killed at least 267 civilians during the December 1995 separatist raid on Gudermes[42]). The dominant Russian strategy was to use heavy artillery and air strikes throughout the campaign, leading some Western and Chechen sources to call the air strikes deliberate terror bombing on parts of Russia.[51] Ironically, due to the fact that ethnic Chechens in Grozny were able to seek refuge among their respective teips in the surrounding villages of the countryside, a high proportion of initial civilian casualties were inflicted against ethnic Russians who were unable to procure viable escape routes. The villages, however, were also heavily targeted from the first weeks of the conflict (Russian cluster bombs, for example, killed at least 55 civilians during the 3 January 1995 Shali cluster bomb attack).

Russian soldiers often prevented civilians from evacuating from areas of imminent danger and prevented humanitarian organizations from assisting civilians in need. It was widely alleged that Russian troops, especially those belonging to the MVD, committed numerous and in part systematic acts of torture and summary executions on separatist sympathizers; they were often linked to zachistka ("cleansing" raids, affecting entire town districts and villages suspected of harboring boyeviki – the separatist fighters). Humanitarian and aid groups chronicled persistent patterns of Russian soldiers killing, raping and looting civilians at random, often in disregard of their nationality. Separatist fighters took hostages on a massive scale, kidnapped or killed Chechens considered to be collaborators, and mistreated civilian captives and federal prisoners of war (especially pilots). Both the separatists and the federal forces kidnapped hostages for ransom and used human shields for cover during the fighting and movement of troops (for example, a group of surrounded Russian troops took approximately 500 civilian hostages at Grozny's 9th Municipal Hospital).[52]

The violations committed by members of the Russian forces were usually tolerated by their superiors and were not punished even when investigated (the story of Vladimir Glebov serving as an example of such policy). However, television and newspaper accounts widely reported largely uncensored images of the carnage to the Russian public. As a result, the Russian media coverage partially precipitated a loss of public confidence in the government and a steep decline in President Yeltsin's popularity. Chechnya was one of the heaviest burdens on Yeltsin's 1996 presidential election campaign. In addition, the protracted War in Chechnya, especially many reports of extreme violence against civilians, ignited fear and contempt of Russia among other ethnic groups in the federation. One of the most notable war crimes committed by Russian forces was the Samashki massacre, on which the United Nations Commission on Human Rights had this to say:

It is reported that a massacre of over 100 people, mainly civilians, occurred between 7 and 8 April 1995 in the village of Samashki, in the west of Chechnya. According to the accounts of 128 eye-witnesses, Federal soldiers deliberately and arbitrarily attacked civilians and civilian dwellings in Samashki by shooting residents and burning houses with flame-throwers. The majority of the witnesses reported that many OMON troops were drunk or under the influence of drugs. They wantonly opened fire or threw grenades into basements where residents, mostly women, elderly persons and children, had been hiding.[53]

Spread of the war[edit]

The declaration by Chechnya's Chief Mufti Akhmad Kadyrov that the ChRI was waging a Jihad (struggle) against Russia raised the spectre that Jihadis from other regions and even outside Russia would enter the war. By one estimate, up to 5,000 non-Chechens served as foreign volunteers, motivated by religious and/or nationalistic reasons.

Limited fighting occurred in the neighbouring small Russian republic of Ingushetia, mostly when Russian commanders sent troops over the border in pursuit of Chechen fighters, while as many as 200,000 refugees (from Chechnya and the conflict in North Ossetia) strained Ingushetia's already weak economy. On several occasions, Ingush president Ruslan Aushev protested incursions by Russian soldiers and even threatened to sue the Russian Ministry of Defence for damages inflicted, recalling how the federal forces previously assisted in the expulsion of the Ingush population from North Ossetia.[54] Undisciplined Russian soldiers were also reported to be committing murders, rapes, and looting in Ingushetia (in an incident partially witnessed by visiting Russian Duma deputies, at least nine Ingush civilians and an ethnic Bashkir soldier were murdered by apparently drunk Russian soldiers; earlier, drunken Russian soldiers killed another Russian soldier, five Ingush villagers and even Ingushetia's health minister).[55]

Much larger and more deadly acts of hostility took place in the republic of Dagestan. In particular, the border village of Pervomayskoye was completely destroyed by Russian forces in January 1996 in reaction to the large-scale Chechen hostage taking in Kizlyar in Dagestan (in which more than 2,000 hostages were taken), bringing strong criticism from this hitherto loyal republic and escalating domestic dissatisfaction. The Don Cossacks of southern Russia, originally sympathetic to the Chechen cause,[citation needed] turned hostile as a result of their Russian-esque culture and language, stronger affinity to Moscow than to Grozny, and a history of conflict with indigenous peoples such as the Chechens. The Kuban Cossacks started organising themselves against the Chechens, including manning paramilitary roadblocks against infiltration of their territories.

Meanwhile, the War in Chechnya spawned new forms of separatist activities in the Russian Federation. Resistance to the conscription of men from minority ethnic groups to fight in Chechnya was widespread among other republics, many of which passed laws and decrees on the subject. For example, the government of Chuvashia passed a decree providing legal protection to soldiers from the republic who refused to participate in the Chechen war and imposed limits on the use of the federal army in ethnic or regional conflicts within Russia. Some regional and local legislative bodies called for the prohibition on the use of draftees in quelling internal conflicts, while others demanded a total ban on the use of the armed forces in such situations. Russian government officials feared that a move to end the war short of victory would create a cascade of secession attempts by other ethnic minorities.

On 16 January 1996, a Turkish passenger ship carrying 200 Russian passengers was taken over by what were mostly Turkish gunmen who were seeking to publicize the Chechen cause. On 6 March, a Cypriot passenger jet was hijacked by Chechen sympathisers while flying toward Germany. Both of these incidents were resolved through negotiations, and the hijackers surrendered without any fatalities being inflicted.

Continuation of the Russian offensive[edit]

On 6 March, between 1,500 and 2,000 Chechen fighters infiltrated Grozny and launched a three-day surprise raid on the city, overrunning much of it and capturing caches of weapons and ammunition. Also in March, Chechen fighters attacked Samashki, where hundreds of villagers were killed. A month later, on 16 April, forces of Arab commander Ibn al-Khattab destroyed a large Russian armored column in an ambush near Shatoy, killing at least 76 soldiers; in another one, near Vedeno, at least 28 Russian troops were killed.[56]

As military defeats and growing casualties made the war more and more unpopular in Russia, and as the 1996 presidential elections neared, Yeltsin's government sought a way out of the conflict. Although a Russian guided missile attack assassinated the ChRI President Dzhokhar Dudayev on 21 April 1996, the separatists persisted. Yeltsin even officially declared "victory" in Grozny on 28 May 1996, after a new temporary ceasefire was signed with the ChRI Acting President Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev.[57][58] While the political leaders were discussing the ceasefire and peace negotiations, military forces continued to conduct combat operations. On 6 August 1996, three days before Yeltsin was to be inaugurated for his second term as Russian president and when most of the Russian Army troops were moved south due to what was planned as their final offensive against remaining mountainous separatist strongholds, the Chechens launched another surprise attack on Grozny.

Third Battle of Grozny and the Khasavyurt Accord[edit]

Despite Russian troops in and around Grozny numbering approximately 12,000, more than 1,500 Chechen guerrillas (whose numbers soon swelled) overran the key districts within hours in an operation prepared and led by Maskhadov (who named it Operation Zero) and Basayev (who called it Operation Jihad). The separatists then laid siege to the Russian posts and bases and the government compound in the city centre, while a number of Chechens deemed to be Russian collaborators were rounded up, detained and, in some cases, executed.[59] At the same time, Russian troops in the cities of Argun and Gudermes were also surrounded in their garrisons. Several attempts by the armored columns to rescue the units trapped in Grozny were repelled with heavy Russian casualties (the 276th Motorized Regiment of 900 men suffered 50% casualties in a two-day attempt to reach the city centre). Russian military officials said that more than 200 soldiers had been killed and nearly 800 wounded in five days of fighting, and that an unknown number were missing; Chechens put the number of Russian dead at close to 1,000. Thousands of troops were either taken prisoner or surrounded and largely disarmed, their heavy weapons and ammunition commandeered by the separatists.

On 19 August, despite the presence of 50,000 to 200,000 Chechen civilians and thousands of federal servicemen in Grozny, the Russian commander Konstantin Pulikovsky gave an ultimatum for Chechen fighters to leave the city within 48 hours, or else it would be leveled in a massive aerial and artillery bombardment. He stated that federal forces would use strategic bombers (not used in Chechnya up to this point) and ballistic missiles. This announcement was followed by chaotic scenes of panic as civilians tried to flee before the army carried out its threat, with parts of the city ablaze and falling shells scattering refugee columns.[60] The bombardment was however soon halted by the ceasefire brokered by General Alexander Lebed, Yeltsin's national security adviser, on 22 August. Gen. Lebed called the ultimatum, issued by General Pulikovsky (now replaced), a "bad joke".[61][62]

During eight hours of subsequent talks, Lebed and Maskhadov drafted and signed the Khasavyurt Accord on 31 August 1996. It included: technical aspects of demilitarization, the withdrawal of both sides' forces from Grozny, the creation of joint headquarters to preclude looting in the city, the withdrawal of all federal forces from Chechnya by 31 December 1996, and a stipulation that any agreement on the relations between the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria and the Russian federal government need not be signed until late 2001.

Aftermath[edit]

Casualties[edit]

According to the General staff of the Russian Armed Forces, 3,826 troops were killed, 17,892 were wounded, and 1,906 are missing in action.[11] According to the NVO, the authoritative Russian independent military weekly, at least 5,362 Russian soldiers died during the war, 52,000 were wounded or became diseased and some 3,000 more remained missing by 2005.[12] The estimate of the Committee of Soldiers' Mothers of Russia, however, put the number of the Russian military dead at 14,000,[21] based on information from wounded troops and soldiers' relatives (counting only regular troops, i.e. not the kontraktniki and special service forces).[63] List of names of the dead soldiers, drawn up by the Human Rights Center "Memorial" contains 4393 names.[64] In 2009, the official Russian number of troops still missing from the two wars in Chechnya and presumed dead was some 700, while about 400 remains of the missing servicemen were said to be recovered up to this point.[65]

According to the World Peace Foundation at Tufts University,

Estimates of the number of civilians killed range widely from 20,000 to 100,000, with the latter figure commonly referenced by Chechen sources. Most scholars and human rights organizations generally estimate the number of civilian casualties to be 40,000; this figure is attributed to the research and scholarship of Chechnya expert John Dunlop, who estimates that the total number of civilian casualties is at least 35,000. This range is also consistent with post-war publications by the Russian statistics office estimating 30,000 to 40,000 civilians killed. The Moscow-based human rights organization, Memorial, which actively documented human rights abuses throughout the war, estimates the number of civilian casualties to be a slightly higher at 50,000.[66]

Russian Interior Minister Anatoly Kulikov claimed that fewer than 20,000 civilians were killed.[67] Médecins Sans Frontières estimated a death toll of 50,000 people out of a population of 1,000,000.[68] Sergey Kovalyov's team could offer their conservative, documented estimate of more than 50,000 civilian deaths. Alexander Lebed asserted that 80,000 to 100,000 had been killed and 240,000 had been injured. The number given by the ChRI authorities was about 100,000 killed.[67]

According to claims made by Sergey Govorukhin and published in the Russian newspaper Gazeta, approximately 35,000 ethnic Russian civilians were killed by Russian forces operating in Chechnya, most of them during the bombardment of Grozny.[69]

Various estimates put the number of Chechens dead or missing between 50,000 and 100,000.[67]

Prisoners and missing persons[edit]

In the Khasavyurt Accord, both sides agreed to an "all for all" exchange of prisoners to be carried out at the end of the war. However, despite this commitment, many persons remained forcibly detained. A partial analysis of the list of 1,432 reported missing found that, as of 30 October 1996, at least 139 Chechens were still being forcibly detained by the Russian side; it was entirely unclear how many of these men were alive.[70] As of mid-January 1997, the Chechens still held between 700 and 1,000 Russian soldiers and officers as prisoners of war, according to Human Rights Watch.[70] According to Amnesty International that same month, 1,058 Russian soldiers and officers were being detained by Chechen fighters who were willing to release them in exchange for members of Chechen armed groups.[71] American freelance journalist Andrew Shumack has been missing from the Chechen capital, Grozny since July 1995 and is presumed dead.[72]

Moscow peace treaty[edit]

The Khasavyurt Accord paved the way for the signing of two further agreements between Russia and Chechnya. In mid-November 1996, Yeltsin and Maskhadov signed an agreement on economic relations and reparations to Chechens who had been affected by the 1994–96 war. In February 1997, Russia also approved an amnesty for Russian soldiers and Chechen separatists alike who committed illegal acts in connection with the War in Chechnya between December 1994 and September 1996.[73]

Six months after the Khasavyurt Accord, on 12 May 1997, Chechen-elected president Aslan Maskhadov traveled to Moscow where he and Yeltsin signed a formal treaty "on peace and the principles of Russian-Chechen relations" that Maskhadov predicted would demolish "any basis to create ill-feelings between Moscow and Grozny."[74] Maskhadov's optimism, however, proved misplaced. Little more than two years later, some of Maskhadov's former comrades-in-arms, led by field commanders Shamil Basayev and Ibn al-Khattab, launched an invasion of Dagestan in the summer of 1999 – and soon Russia's forces entered Chechnya again, marking the beginning of the Second Chechen War.

Foreign policy implications[edit]

From the outset of the First Chechen conflict, Russian authorities struggled to reconcile new international expectations with widespread accusations of Soviet-style heaviness in their execution of the war. For example, Foreign minister Kozyrev, who was generally regarded as a Western-leaning liberal, made the following remark when questioned about Russia's conduct during the war; "‘Generally speaking, it is not only our right but our duty not to allow uncontrolled armed formations on our territory. The Foreign Ministry stands on guard over the country's territorial unity. International law says that a country not only can but must use force in such instances ... I say it was the right thing to do ... The way in which it was done is not my business."[75] These attitudes contributed greatly to the growing doubts in the West as to whether Russia was sincere in its stated intentions to implement democratic reforms. The general disdain for Russian behavior in the Western political establishment contrasted heavily with widespread support in the Russian public.[76] Domestic political authorities' arguments emphasizing stability and the restoration of order resonated with the public and quickly became an issue of state identity.

See also[edit]

- begin quote from:

- Second Chechen War

Second Chechen War

| Second Chechen War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Chechen–Russian conflict and Post-Soviet conflicts | |||||||||

Russian artillery shelling Chechen positions near the village of Duba-Yurt in January 2000 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Foreign volunteers: | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

(until 31 December 1999) (after 31 December 1999) | (assassinated in exile) | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 80,000 (in 1999)[10] | Russian claim: ~22,000[11]–30,000[12] (in 1999) | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 3,536–3,635 soldiers killed,[13][14] 2,364–2,572 Interior ministry troops killed,[15][16][17] 1,072 Chechen police officers killed,[18][19] 106 FSB and GRU operatives killed[20] Total killed: 7,217–7,425* | Russian claim: 14,113 militants killed (1999–2002)[21] 2,186 militants killed (2003–2009)[22] Total killed: 16,299 | ||||||||

Civilian casualties: Total killed military/civilian: ~50,000–80,000 Others estimate: ~150,000–250,000 | |||||||||

| *The Committee of Soldiers' Mothers group disputed the official government count of the number of war dead and claimed that 14,000 Russian servicemen were killed during the war from 1999 to 2005.[30] | |||||||||

The Second Chechen War (Russian: Втора́я чече́нская война́, Chechen: ШолгIа оьрсийн-нохчийн тIом, lit. 'Second Russian-Chechen War'[31]) was an armed conflict in Chechnya and the border regions of the North Caucasus between the Russian Federation and the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, fought from August 1999 to April 2000.

In August 1999, Islamist fighters from Chechnya infiltrated Russia's Dagestan region, declaring it an independent state and calling for holy war. During the initial campaign, Russian military and pro-Russian Chechen paramilitary forces faced Chechen separatists in open combat and seized the Chechen capital Grozny after a winter siege that lasted from December 1999 until February 2000. Russia established direct rule over Chechnya in May 2000 although Chechen militant resistance throughout the North Caucasus region continued to inflict heavy Russian casualties and challenge Russian political control over Chechnya for several years. Both sides carried out attacks against civilians. These attacks drew international condemnation.

In mid-2000, the Russian government transferred certain military responsibilities to pro-Russian Chechen forces. The military phase of operations was terminated in April 2002, and the coordination of the field operations was given first to the Federal Security Service and then to the Ministry of Internal Affairs in the summer of 2003.

By 2009, Russia had severely disabled the Chechen separatist movement and large-scale fighting ceased. Russian army and interior ministry troops ceased patrolling. Grozny underwent reconstruction efforts and much of the city and surrounding areas were rebuilt quickly. Sporadic violence continued throughout the North Caucasus; occasional bombings and ambushes targeting federal troops and forces of the regional governments in the area still occur.[32][33]

In April 2009, the government operation in Chechnya officially ended.[9] As the bulk of the army was withdrawn, the responsibility for dealing with the low-level insurgency was shouldered by the local police force. Three months later, the exiled leader of the separatist government, Akhmed Zakayev, called for a halt to armed resistance against the Chechen police force from August and said he hoped that "starting with this day Chechens will never shoot at each other".[34] This marked the complete end of the Chechen conflict.

The exact death toll of the conflict is unknown. Russian casualties are around 7,500 (official Russian casualty figures)[35] or about 14,000 according to the Committee of Soldiers' Mothers.[36] Unofficial sources estimate a range of 25,000 to 50,000 dead or missing, mostly Chechen civilians.[37]

Contents

Names[edit]

The Second Chechen war is also known as the Second Chechen Campaign (Russian: Втора́я чече́нская кампа́ния)[a][38] or the Second Russian invasion of Chechnya from the rebel Chechen point of view.

Historical basis of the conflict[edit]

Russian Empire[edit]

Chechnya is an area in the Northern Caucasus which has constantly fought against foreign rule, including the Ottoman Turks in the 15th century. The Russian Terek Cossack Host was established in lowland Chechnya in 1577 by free Cossacks who were resettled from the Volga to the Terek River. In 1783, Russia and the Georgian kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti signed the Treaty of Georgievsk, under which Kartl-Kakheti became a Russian protectorate.[39] To secure communications with Georgia and other regions of the Transcaucasia, the Russian Empire began spreading its influence into the Caucasus region, starting the Caucasus War in 1817. Russian forces first moved into highland Chechnya in 1830, and the conflict in the area lasted until 1859, when a 250,000-strong army under General Baryatinsky broke down the highlanders' resistance. Frequent uprisings in the Caucasus also occurred during the Russo-Turkish War, 1877–78.

Soviet Union[edit]

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, Chechens established a short-lived Caucasian Imamate which included parts of Chechnya, Dagestan and Ingushetia; there was also the secular pan-Caucasian Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus.[40] The Chechen states were opposed[citation needed] by both sides of the Russian Civil War and most of the resistance was crushed by Bolshevik troops by 1922. Then, months before the creation of the Soviet Union, the Chechen Autonomous Oblast of the Russian SFSR was established. It annexed a part of territory of the former Terek Cossack Host. Chechnya and neighboring Ingushetia formed the Chechen–Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic in 1936. In 1941, during World War II, a Chechen revolt broke out, led by Khasan Israilov. In 1944 Chechens were deported to the Kazakh and Kirghiz SSRs in an act of ethnic cleansing; this was done under the false pretext of Chechen mass collaboration with Nazi Germany. An estimated 1/4 to 1/3 of the Chechen population perished due the harsh conditions.[41][42][43] Many scholars recognize the deportation as an act of genocide, as did the European Parliament in 2004.[44][45][46] In 1992 the separatist government built a memorial dedicated to the victims of the acts of 1944. The Pro-Russian government would later demolish this memorial.[47][48] Tombstones which were an integral part of the memorial were found planted on the Akhmad Kadyrov Place next to granite steles honoring the losses of the local pro-Russian power.[49]

First Chechen War[edit]

During the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Chechnya declared independence. In 1992, Chechen and Ingush leaders signed an agreement splitting the joint Chechen–Ingush republic in two, with Ingushetia joining the Russian Federation and Chechnya remaining independent. The debate over independence ultimately led to a small-scale civil war since 1992, in which the Russians covertly tried to oust the government of Dzhokhar Dudayev. The First Chechen War began in 1994, when Russian forces entered Chechnya to restore constitutional order. Following nearly two years of brutal fighting, with a death toll exceeding one hundred thousand by some estimates, the 1996 Khasavyurt ceasefire agreement was signed and Russian troops were withdrawn from the republic.[50]

Prelude to the Second Chechen War[edit]

Chaos in Chechnya[edit]

Following the first war, the government's grip on the chaotic republic was weak, especially outside the ruined capital Grozny. The areas controlled by separatist groups grew larger and the country became increasingly lawless.[51] The war ravages and lack of economic opportunities left large numbers of heavily armed and brutalized former separatist fighters with no occupation but further violence. The authority of the government in Grozny was opposed by extremist warlords like Arbi Barayev who according to some sources was in cooperation with the FSB.[52] Abductions and raids into other parts of the Northern Caucasus by various Chechen warlords had been steadily increasing.[53] In place of the devastated economic structure, kidnapping emerged as the principal source of income countrywide, procuring over $200 million during the three-year independence of the chaotic fledgling state.[54] It has been estimated that up to 1,300 people were kidnapped in Chechnya between 1996 and 1999,[51] and in 1998 a group of four Western hostages was murdered. In 1998, a state of emergency was declared by the authorities in Grozny. Tensions led to open clashes like the July 1998 confrontation in Gudermes in which some 50 people died in fighting between Chechen National Guard troops and the Islamist militias.

Russian–Chechen relations 1996–1999[edit]

Political tensions were fueled in part by allegedly Chechen or pro-Chechen terrorist and criminal activity in Russia, as well as by border clashes. On 16 November 1996, in Kaspiysk (Dagestan), a bomb destroyed an apartment building housing Russian border guards, killing 68 people. The cause of the blast was never determined, but many in Russia blamed Chechen separatists.[55] Three people died on 23 April 1997, when a bomb exploded in the Russian railway station of Armavir (Krasnodar Krai), and two on 28 May 1997, when another bomb exploded in the Russian railway station of Pyatigorsk (Stavropol Krai). On 22 December 1997, forces of Dagestani militants and Chechnya-based Arab warlord Ibn al-Khattab raided the base of the 136th Motor Rifle Brigade of the Russian Army in Buynaksk, Dagestan, inflicting heavy casualties.[56]

The 1997 election brought to power the separatist president Aslan Maskhadov. In 1998 and 1999, President Maskhadov survived several assassination attempts,[57] blamed on the Russian intelligence services. In March 1999, General Gennady Shpigun, the Kremlin's envoy to Chechnya, was kidnapped at the airport in Grozny and ultimately found dead in 2000 during the war. On 7 March 1999, in response to the abduction of General Shpigun, Interior Minister Sergei Stepashin called for an invasion of Chechnya. However, Stepashin's plan was overridden by the prime minister, Yevgeny Primakov.[58] Stepashin later said:[59]

The decision to invade Chechnya was made in March 1999... I was prepared for an active intervention. We were planning to be on the north side of the Terek River by August–September [of 1999] This [the war] would happen regardless to the bombings in Moscow... Putin did not discover anything new. You can ask him about this. He was the director of FSB at this time and had all the information.[60][61]

According to Robert Bruce Ware, these plans should be regarded as contingency plans. However, Stepashin did actively call for a military campaign against Chechen separatists in August 1999 when he was the prime minister of Russia. But shortly after his televised interview where he talked about plans to restore constitutional order in Chechnya, he was replaced in the PM's position by Vladimir Putin.[62]

In late May 1999, Russia announced that it was closing the Russian-Chechnya border in an attempt to combat attacks and criminal activity; border guards were ordered to shoot suspects on sight. On 18 June 1999, seven servicemen were killed when Russian border guard posts were attacked in Dagestan. On 29 July 1999, the Russian Interior Ministry troops destroyed a Chechen border post and captured an 800-meter section of strategic road. On 22 August 1999, 10 Russian policemen were killed by an anti-tank mine blast in North Ossetia, and, on 9 August 1999, six servicemen were kidnapped in the Ossetian capital Vladikavkaz.

Invasion of Dagestan[edit]

The Invasion of Dagestan was the trigger for the Second Chechen War. On 7 August 1999, Shamil Basayev (in association with the Saudi-born Ibn al-Khattab, Commander of the Mujahedeen) led two armies of up to 2,000 Chechen, Dagestani, Arab and international mujahideen and Wahhabist militants from Chechnya into the neighboring Republic of Dagestan. This war saw the first (unconfirmed) use of aerial-delivered fuel air explosives (FAE) in mountainous areas, notably in the village of Tando.[63] By mid-September 1999, the militants were routed from the villages they had captured and pushed back into Chechnya. At least several hundred militants were killed in the fighting; the Federal side reported 275 servicemen killed and approximately 900 wounded.[64]

Bombings in Russia[edit]

Before the wake of the Dagestani invasion had settled, a series of bombings took place in Russia (in Moscow and in Volgodonsk) and in the Dagestani town of Buynaksk. On 4 September 1999, 62 people died in an apartment building housing members of families of Russian soldiers. Over the next two weeks, the bombs targeted three other apartment buildings and a mall; in total over 350 people were killed. A criminal investigation of the bombings was completed in 2002. The results of the investigation, and the court ruling that followed, concluded that they were organized by Achemez Gochiyaev, who remains at large, and ordered by Khattab and Abu Omar al-Saif (both of whom were later killed), in retaliation for the Russian counteroffensive against their incursion into Dagestan. Six other suspects have been convicted by Russian courts. However, Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) agents were caught by local police for planting one of the bombs, but were later released on orders from Moscow.[65] Many observers, including State Duma deputies Yuri Shchekochikhin, Sergei Kovalev and Sergei Yushenkov, cast doubts on the official version and sought an independent investigation. Some others, including David Satter, Yury Felshtinsky, Vladimir Pribylovsky and Alexander Litvinenko, as well as the secessionist Chechen authorities, claimed that the 1999 bombings were a false flag attack coordinated by the FSB in order to win public support for a new full-scale war in Chechnya, which boosted the popularity of Prime Minister and former FSB Director Vladimir Putin, brought the pro-war Unity Party to the State Duma in the 1999 parliamentary election, and secured Putin as president within a few months.[66][67][68][69][70][71][72]

1999–2000 Russian offensive[edit]

Air war[edit]

In late August and early September 1999, Russia mounted a massive aerial campaign over Chechnya, with the stated aim of wiping out militants who invaded Dagestan earlier in the same month. On 26 August 1999, Russia acknowledged bombing raids in Chechnya.[73] The Russian air strikes were reported to have forced at least 100,000 Chechens to flee their homes to safety; the neighbouring region of Ingushetia was reported to have appealed for United Nations aid to deal with tens of thousands of refugees.[74] On 2 October 1999, Russia's Ministry of Emergency Situations reported that 78,000 people had fled the air strikes in Chechnya; most of them went to Ingushetia, where they were arrived at a rate of 5,000 to 6,000 a day.

As of 22 September 1999, Deputy Interior Minister Igor Zubov said that Russian troops had surrounded Chechnya and were prepared to retake the region, but the military planners were advising against a ground invasion because of the likelihood of heavy Russian casualties.

Land war[edit]

The Chechen conflict entered a new phase on 1 October 1999, when Russia's new Prime Minister Vladimir Putin declared the authority of Chechen President Aslan Maskhadov and his parliament illegitimate.[citation needed] At this time, Putin announced that Russian troops would initiate a land invasion but progress only as far as the Terek River, which cuts the northern third of Chechnya off from the rest of the republic. Putin's stated intention was to take control of Chechnya's northern plain and establish a cordon sanitaire against further Chechen aggression; he later recalled that the cordon alone was "pointless and technically impossible," apparently because of Chechnya's rugged terrain. According to Russian accounts, Putin accelerated a plan for a major crackdown against Chechnya that had been drawn up months earlier.[75]

The Russian army moved with ease in the wide open spaces of northern Chechnya and reached the Terek River on 5 October 1999. On this day, a bus filled with refugees was reportedly hit by a Russian tank shell, killing at least 11 civilians;[76] two days later, Russian Su-24 fighter bombers dropped cluster bombs on the village of Elistanzhi, killing some 35 people.[77] On 10 October 1999, Maskhadov outlined a peace plan offering a crackdown on renegade warlords;[77] the offer was rejected by the Russian side. He also appealed to NATO to help end fighting between his forces and Russian troops, without effect.[78]

On 12 October 1999, the Russian forces crossed the Terek and began a two-pronged advance on the capital Grozny to the south. Hoping to avoid the significant casualties that plagued the first Chechen War, the Russians advanced slowly and in force, making extensive use of artillery and air power in an attempt to soften Chechen defences. Many thousands of civilians fled the Russian advance, leaving Chechnya for neighbouring Russian republics. Their numbers were later estimated to reach 200,000 to 350,000, out of the approximately 800,000 residents of the Chechen Republic. The Russians appeared to be taking no chances with the Chechen population in its rear areas, setting up "filtration camps" in October in northern Chechnya for detaining suspected members of bandformirovaniya militant formations (literally: "bandit formations").

On 15 October 1999, Russian forces took control of a strategic ridge within artillery range of the Chechen capital Grozny after mounting an intense tank and artillery barrage against Chechen fighters. In response, President Maskhadov declared a gazavat (holy war) to confront the approaching Russian army. Martial law was declared in Ichkeria and reservists were called, but no martial law or state of emergency had been declared in Chechnya or Russia by the Russian government.[79] The next day, Russian forces captured the strategic Tersky Heights, within sight of Grozny, dislodging 200 entrenched Chechen fighters. After heavy fighting, Russia seized the Chechen base in the village of Goragorsky, west of the city.[80]

On 21 October 1999, a Russian Scud short-range ballistic missile strike on the central Grozny marketplace killed more than 140 people, including many women and children, and left hundreds more wounded. A Russian spokesman said the busy market was targeted because it was used by separatists as an arms bazaar.[81] Eight days later Russian aircraft carried out a rocket attack on a large convoy of refugees heading into Ingushetia, killing at least 25 civilians including Red Cross workers and journalists.[82] Two days later Russian forces conducted a heavy artillery and rocket attack on Samashki; some claimed that civilians were killed in Samashki in revenge for the heavy casualties suffered there by Russian forces during the first war.[83]

On 12 November 1999, the Russian flag was raised over Chechnya's second largest city, Gudermes, when the local Chechen commanders, the Yamadayev brothers, defected to the federal side; the Russians also entered the bombed-out former Cossack village of Assinovskaya. The fighting in and around Kulary continued until January 2000. On 17 November 1999, Russian soldiers dislodged separatists in Bamut, the symbolic separatist stronghold in the first war; dozens of Chechen fighters and many civilians were reported killed, and the village was levelled in the FAE bombing. Two days later, after a failed attempt five days earlier, Russian forces managed to capture the village of Achkhoy-Martan.

On 26 November 1999, Deputy Army Chief of Staff Valery Manilov said that phase two of the Chechnya campaign was just about complete, and a final third phase was about to begin. According to Manilov, the aim of the third phase was to destroy "bandit groups" in the mountains. A few days later Russia's Defense Minister Igor Sergeyev said Russian forces might need up to three more months to complete their military campaign in Chechnya, while some generals said the offensive could be over by New Year's Day. The next day the Chechens briefly recaptured the town of Novogroznensky.[84]

On 1 December 1999, after weeks of heavy fighting, Russian forces under Major General Vladimir Shamanov took control of Alkhan-Yurt, a village just south of Grozny. The Chechen and foreign fighters inflicted heavy losses on the Russian forces, reportedly killing more than 70 Russian soldiers before retreating,[85] suffering heavy losses of their own.[86] On the same day, Chechen separatist forces began carrying out a series of counter-attacks against federal troops in several villages as well as in the outskirts of Gudermes. Chechen fighters in Argun, a small town five kilometres east of Grozny, put up some of the strongest resistance to federal troops since the start of Moscow's military offensive.[citation needed] The separatists in the town of Urus-Martan also offered fierce resistance, employing guerilla tactics Russia had been anxious to avoid; by 9 December 1999, Russian forces were still bombarding Urus-Martan, although Chechen commanders said their fighters had already pulled out.[citation needed]

On 4 December 1999, the commander of Russian forces in the North Caucasus, General Viktor Kazantsev, claimed that Grozny was fully blockaded by Russian troops. The Russian military's next task was the seizure of the town of Shali, 20 kilometres south-east of the capital, one of the last remaining separatist-held towns apart from Grozny. Russian troops started by capturing two bridges that link Shali to the capital, and by 11 December 1999, Russian troops had encircled Shali and were slowly forcing separatists out. By mid-December the Russian military was concentrating attacks in southern parts of Chechnya and preparing to launch another offensive from Dagestan.

Siege of Grozny[edit]

The Russian assault on Grozny began in early December, accompanied by a struggle for neighbouring settlements. The battle ended when the Russian army seized the city on 2 February 2000. According to official Russian figures, at least 134 federal troops and an unknown number of pro-Russian militiamen died in Grozny. The separatist forces also suffered heavy losses, including losing several top commanders. Russian Defense Minister Igor Sergeyev said that 2,700 separatists were killed trying to leave Grozny. The separatists said they lost at least 500 fighters in the mine field at Alkhan-Kala.[87]

The siege and fighting devastated the capital like no other European city since World War II. In 2003 the United Nations called Grozny the most destroyed city on Earth.[88]

The Russians also suffered heavy losses as they advanced elsewhere, and from Chechen counterattacks and convoy ambushes. On 26 January 2000, the Russian government announced that 1,173 servicemen had been killed in Chechnya since October,[89] more than double the 544 killed reported just 19 days earlier.[90]

Battle for the mountains[edit]

Heavy fighting accompanied by massive shelling and bombing continued through the winter of 2000 in the mountainous south of Chechnya, particularly in the areas around Argun, Vedeno and Shatoy, where fighting involving Russian paratroopers had raged since 1999.

On 9 February 2000, a Russian tactical missile hit a crowd of people who had come to the local administration building in Shali, a town previously declared as one of the "safe areas", to collect their pensions. The attack was a response to a report that a group of fighters had entered the town. The missile is estimated to have killed some 150 civilians, and was followed by an attack by combat helicopters causing further casualties.[91] Human Rights Watch called on the Russian military to stop using FAE, known in Russia as "vacuum bombs", in Chechnya, concerned about the large number of civilian casualties caused by what it called "widespread and often indiscriminate bombing and shelling by Russian forces".[92] On 18 February 2000, a Russian army transport helicopter was shot down in the south, killing 15 men aboard, Russian Interior Minister Vladimir Rushailo announced in a rare admission by Moscow of losses in the war.[93]

On 29 February 2000, United Army Group commander Gennady Troshev said that "the counter-terrorism operation in Chechnya is over. It will take a couple of weeks longer to pick up splinter groups now." Russia's Defense Minister, Marshal of the Russian Federation Igor Sergeyev, evaluated the numerical strength of the separatists at between 2,000 and 2,500 men, "scattered all over Chechnya." On the same day, a Russian VDV paratroop company from Pskov was attacked by Chechen and Arab fighters near the village of Ulus-Kert in Chechnya's southern lowlands; at least 84 Russian soldiers were killed in the especially heavy fighting.[citation needed] The official newspaper of the Russian Ministry of Defense reported that at least 659 separatists were killed, including 200 from the Middle East, figures which they said were based on radio-intercept data, intelligence reports, eyewitnesses, local residents and captured Chechens.[94] On 2 March 2000, an OMON unit from Podolsk opened fire on a unit from Sergiyev Posad in Grozny; at least 24 Russian servicemen were killed in the incident.

In March a large group of more than 1,000 Chechen fighters, led by field commander Ruslan Gelayev, pursued since their withdrawal from Grozny, entered the village of Komsomolskoye in the Chechen foothills and held off a full-scale Russian attack on the town for over two weeks;[citation needed] they suffered hundreds of casualties,[citation needed] while the Russians admitted to more than 50 killed. On 29 March 2000, about 23 Russian soldiers were killed in a separatist ambush on an OMON convoy from Perm in Zhani-Vedeno.

On 23 April 2000, a 22-vehicle convoy carrying ammunition and other supplies to an airborne unit was ambushed near Serzhen-Yurt in the Vedeno Gorge by an estimated 80 to 100 "bandits", according to General Troshev. In the ensuing four-hour battle the federal side lost 15 government soldiers, according to the Russian defence minister. General Troshev told the press that the bodies of four separatist fighters were found. The Russian Airborne Troops headquarters later stated that 20 separatists were killed and two taken prisoner.[95] Soon, the Russian forces seized the last populated centres of the organized resistance. (Another offensive against the remaining mountain strongholds was launched by Russian forces in December 2000.)

Restoration of federal government[edit]

Russian President Vladimir Putin established direct rule of Chechnya in May 2000. The following month, Putin appointed Akhmad Kadyrov interim head of the pro-Moscow government. This development met with early approval in the rest of Russia, but the continued deaths of Russian troops dampened public enthusiasm. On 23 March 2003, a new Chechen constitution was passed in a referendum. The 2003 Constitution granted the Chechen Republic a significant degree of autonomy, but still tied it firmly to Russia and Moscow's rule, and went into force on 2 April 2003. The referendum was strongly supported by the Russian government but met a harsh critical response from Chechen separatists; many citizens chose to boycott the ballot.[citation needed] Akhmad Kadyrov was assassinated by a bomb blast in 2004. Since December 2005, his son Ramzan Kadyrov, leader of the pro-Moscow militia known as kadyrovtsy, has been functioning as the Chechnya's de facto ruler. Kadyrov has become Chechnya's most powerful leader and, in February 2007, with support from Putin, Ramzan Kadyrov replaced Alu Alkhanov as president.

Insurgency[edit]

Guerrilla war in Chechnya[edit]

Although large-scale fighting within Chechnya had ceased, daily attacks continued, particularly in the southern portions of Chechnya and spilling into nearby territories of the Caucasus, especially after the Caucasus Front was established. Typically small separatist units targeted Russian and pro-Russian officials, security forces, and military and police convoys and vehicles. The separatist units employed IEDs and sometimes combined for larger raids. Russian forces retaliated with artillery and air strikes, as well as counter-insurgency operations. Most soldiers in Chechnya were kontraktniki (contract soldiers) as opposed to the earlier conscripts. While Russia continued to maintain a military presence within Chechnya, federal forces played less of a direct role. Pro-Kremlin Chechen forces under the command of the local strongman Ramzan Kadyrov, known as the kadyrovtsy, dominated law enforcement and security operations, with many members (including Kadyrov himself) being former Chechen separatists who had defected since 1999. Since 2004, the Kadyrovtsy were partly incorporated into two Interior Ministry units, North and South (Sever and Yug). Two other units of the Chechen pro-Moscow forces, East and West (Vostok and Zapad), were commanded by Sulim Yamadayev (Vostok) and Said-Magomed Kakiyev (Zapad) and their men.[96]

On 16 April 2009, the head of the Federal Security Service, Alexander Bortnikov, announced that Russia had ended its "anti-terror operation" in Chechnya, claiming that stability had been restored to the territory.[97] "The decision is aimed at creating the conditions for the future normalisation of the situation in the republic, its reconstruction and development of its socio-economic sphere," Bortnikov stated. While Chechnya had largely stabilised, there were still clashes with militants in the nearby regions of Dagestan and Ingushetia.

Suicide attacks[edit]

Between June 2000 and September 2004, Chechen insurgents added suicide attacks to their tactics. During this period, there were 23 Chechen-related suicide attacks in and outside Chechnya, notably the hostage taking at an elementary school in Beslan, in which at least 334 people died.

Assassinations[edit]

Both sides of the war carried out multiple assassinations. The most prominent of these included the 13 February 2004 killing of exiled former separatist Chechen President Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev in Qatar, and the 9 May 2004 killing of pro-Russian Chechen President Akhmad Kadyrov during a parade in Grozny.

Caucasus Front[edit]

While anti-Russian local insurgencies in the North Caucasus started even before the war, in May 2005, two months after Maskahdov's death, Chechen separatists officially announced that they had formed a Caucasus Front within the framework of "reforming the system of military–political power." Along with the Chechen, Dagestani and Ingush "sectors," the Stavropol, Kabardin-Balkar, Krasnodar, Karachai-Circassian, Ossetian and Adyghe jamaats were included. This meant that practically all the regions of Russia's south were involved in the hostilities.

The Chechen separatist movement took on a new role as the official ideological, logistical and, probably, financial hub of the new insurgency in the North Caucasus.[98] Increasingly frequent clashes between federal forces and local militants continued in Dagestan, while sporadic fighting erupted in the other southern Russia regions, such as Ingushetia, and notably in Nalchik on 13 October 2005.

Human rights and terrorism[edit]

Human rights and war crimes[edit]

Russian officials and Chechen separatists have regularly and repeatedly accused the opposing side of committing various war crimes including kidnapping, murder, hostage taking, looting, rape, and assorted other breaches of the laws of war. International and humanitarian organizations, including the Council of Europe and Amnesty International, have criticized both sides of the conflict for "blatant and sustained" violations of international humanitarian law.

Western European rights groups estimate there have been about 5,000 forced disappearances in Chechnya since 1999.[99]

American Secretary of State Madeleine Albright noted in her 24 March 2000 speech to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights:

- We cannot ignore the fact that thousands of Chechen civilians have died and more than 200,000 have been driven from their homes. Together with other delegations, we have expressed our alarm at the persistent, credible reports of human rights violations by Russian forces in Chechnya, including extrajudicial killings. There are also reports that Chechen separatists have committed abuses, including the killing of civilians and prisoners.... The war in Chechnya has greatly damaged Russia's international standing and is isolating Russia from the international community. Russia's work to repair that damage, both at home and abroad, or its choice to risk further isolating itself, is the most immediate and momentous challenge that Russia faces.[100]

According to the 2001 annual report by Amnesty International:

- There were frequent reports that Russian forces indiscriminately bombed and shelled civilian areas. Chechen civilians, including medical personnel, continued to be the target of military attacks by Russian forces. Hundreds of Chechen civilians and prisoners of war were extra judicially executed. Journalists and independent monitors continued to be refused access to Chechnya. According to reports, Chechen fighters frequently threatened, and in some cases killed, members of the Russian-appointe civilian administration and executed Russian captured soldiers.[101]

The Russian government failed to pursue any accountability process for human rights abuses committed during the course of the conflict in Chechnya. Unable to secure justice domestically, hundreds of victims of abuse have filed applications with the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). In March 2005 the court issued the first rulings on Chechnya, finding the Russian government guilty of violating the right to life and even the prohibition of torture with respect to civilians who had died or forcibly disappeared at the hands of Russia's federal troops.[102] Many similar claims were ruled since against Russia.

Dozens of mass graves containing hundreds of corpses have been uncovered since the beginning of the First Chechen War in 1994. As of June 2008, there were 57 registered locations of mass graves in Chechnya.[103] According to Amnesty International, thousands may be buried in unmarked graves including up to 5,000 civilians who disappeared since the beginning of the Second Chechen War in 1999.[104] In 2008, the largest mass grave found to date was uncovered in Grozny, containing some 800 bodies from the First Chechen War in 1995.[103] Russia's general policy to the Chechen mass graves is to not exhume them.[105]

Terrorist attacks[edit]

Between May 2002 and September 2004, the Chechen and Chechen-led militants, mostly answering to Shamil Basayev, launched a campaign of terrorism directed against civilian targets in Russia. About 200 people were killed in a series of bombings (most of them suicide attacks), most of them in the 2003 Stavropol train bombing (46), the 2004 Moscow metro bombing (40), and the 2004 Russian aircraft bombings (89).

Two large-scale hostage takings, the 2002 Moscow theater hostage crisis and the 2004 Beslan school siege, resulted in the deaths of multiple civilians. In the Moscow stand-off, FSB Spetsnaz forces stormed the building on the third day using an unknown incapacitating chemical agent that proved to be lethal without sufficient medical care, resulting in deaths of 133 out of 916 hostages. In Beslan, some 20 hostages had been executed by their captors before the assault, and the ill-prepared assault itself (started hastily after explosions in the gym that had been rigged with explosives by the terrorists) resulted in 294 more casualties among the 1128 hostages, as well as heavy losses among the special forces.

Other issues[edit]

Pankisi crisis[edit]

Russian officials have accused the bordering republic of Georgia of allowing Chechen separatists to operate on Georgian territory and permitting the flow of militants and materiel across the Georgian border with Russia. In February 2002, the United States began offering assistance to Georgia in combating "criminal elements" as well as alleged Arab mujahideen activity in Pankisi Gorge as part of the War on Terrorism. Without resistance, Georgian troops have detained an Arab man and six criminals, and declared the region under control.[106] In August 2002, Georgia accused Russia of a series of secret air strikes on purported separatists havens in the Pankisi Gorge in which a Georgian civilian was reported killed.

On 8 October 2001, a UNOMIG helicopter was shot down in Georgia in Kodori Valley gorge near Abkhazia, amid fighting between Chechens and Abkhazians, killing nine including five UN observers.[107] Georgia denied having troops in the area, and the suspicion fell on the armed group headed by Chechen warlord Ruslan Gelayev, who was speculated to have been hired by the Georgian government to wage proxy war against separatist Abkhazia. On 2 March 2004, following a number of cross-border raids from Georgia into Chechnya, Ingushetia, and Dagestan, Gelayev was killed in a clash with Russian border guards while trying to get back from Dagestan into Georgia.

Unilateral ceasefire of 2005[edit]