Scott Heins/Getty Images

Can Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Save the Planet?

Democrats lack an organized plan to stop global warming. Climate scientists say the newcomer has the beginnings of a good one.

Progressives have been practically leaping for joy since 28-year-old self-described democratic socialist Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez won her primary election for Congress last week, an outcome that CNN called “the most shocking upset of a rollicking political season.” But perhaps no group has been more excited than environmentalists. In a political environment where even her fellow Democrats often stay vague on climate change, Ocasio-Cortez has been specific and blunt in talking about the global warming crisis. She also has a plan to fight that crisis—one to transition the United States to a 100-percent renewable energy system by 2035.

To achieve this ambitious goal, she has proposed implementing what she calls a “Green New Deal,” a Franklin Delano Roosevelt–like plan to spur “the investment of trillions of dollars and the creation of millions of high-wage jobs,” according to her official website. “The Green New Deal we are proposing will be similar in scale to the mobilization efforts seen in World War II or the Marshall Plan,” she told HuffPost last week. “We must again invest in the development, manufacturing, deployment, and distribution of energy, but this time green energy.”

These positions have earned Ocasio-Cortez significant positive press. HuffPost called her “The Leading Democrat On Climate Change;” Vice called her “the Climate Change Hardliner the Planet Needs.” But those stories also note the political obstacles in Ocasio-Cortez’s way. There’s the climate-denying Republican Party, of course, but there are also Democrats, who have largely ignored climate change this election season and lack an organized plan to tackle it. How can a plan like Ocasio-Cortez’s see the light of day when her own party seems likely to bury it?

But an equally important question is whether such a plan would, from the scientific perspective, work. Very few plans politicians have floated recently have even come close to the level of drastic change researchers say the world would need in order to halt global warming before it reaches dangerous levels. How does this one stack up?

If and when Democrats do decide to mobilize on global warming, climate scientists tell me their plan should look at least something like Ocasio-Cortez’s. “A plan of the magnitude and pace proposed by Ms. Ocasio-Cortez would be a critically important step in the right direction, albeit long overdue,” said Jennifer Francis, a research professor at Rutgers University’s Institute of Marine and Coastal Sciences. Michael Mann, director of the Earth System Science Center at Penn State, agreed. “This is just the sort of audacious and bold thinking we will need if we are going to avert a climate crisis,” he said.

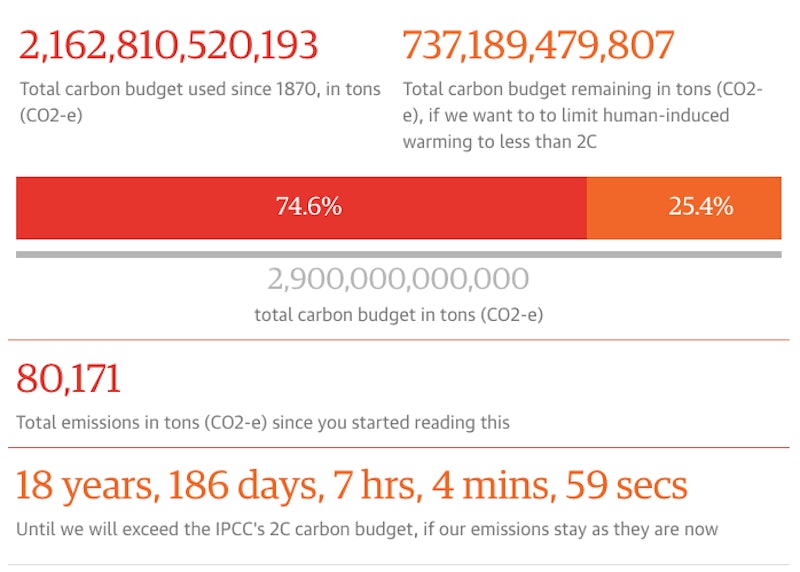

Climate scientists overwhelmingly agree that aggressive action is needed to stave off the violent storms, rising seas, and debilitating droughts projected to worsen as the climate warms. Avoiding that means the earth’s average temperature can’t rise more than 2 degrees Celsius above where it was in the year 1880. Unfortunately, we’re already nearly there; as The Guardian’s Carbon Countdown Clock shows, humans can only emit greenhouse gases at our current rate for another 18 years before we reach the 2-degree mark. We can buy more time, however, if we stop emitting so much greenhouse gas. “The science is pretty clear—we want to reduce emissions, to near zero, as fast as possible, if we want to minimize climate change,” Texas A&M University climate scientist Andrew Dessler told me. That means rapidly decarbonizing the U.S. economy—much like Ocasio-Cortez has proposed.

But for most of the the climate scientists I spoke to, their alignment with Ocasio-Cortez’s plan stops there. That’s not because they don’t want a 100-percent renewable energy system by 2035, but because the Green New Deal lacks some important details. “How will energy be stored as an economical cost if only using wind and solar? What is the role for nuclear power in such a plan? Who will fund this transition?” said Penn State climate scientist David Titley, also the former chief operating officer of NOAA. “I’m very skeptical such a transition can be done in a period less than 20 years from what is basically a standing start.”

How the Green New Deal would be paid for was a common point of contention—after all, Roosevelt’s New Deal was paid for by massive cuts in government spending, tax hikes, and decreased pay for government workers. “This would, I think, not be something that Republicans would support,” Dessler said, stating the obvious. Kevin Trenberth, a distinguished senior climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, said he believed a gradually implemented carbon tax would be the only way to garner support for the plan. “This provides all kinds of incentives, gets the private sector engaged, and implements it in a way that is not a shock to the system but which allows good planning to occur,” he said.

The climate scientists I spoke to also noted that quickly transitioning to renewable energy wouldn’t be enough to completely solve the climate crisis, because we’ve already emitted so much carbon dioxide and will continue to inevitably for at least two decades. (You can’t take all the cars off the road at once.) “The heat-trapping greenhouse gases already in the atmosphere will remain there for at least a century and cause additional impacts,” Francis said. “For this reason, the plan to convert to renewable energy sources must be accompanied by efforts and resources to develop technology that can remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, along with a carbon fee to discourage further extraction and burning of fossil fuels.” A comprehensive climate change plan must also account for adaptation to those inevitable impacts. After all, “Climate change is already with us and costing billions per year,” Trenberth noted.

Ocasio-Cortez’s plan to fight climate change may raise important and difficult questions, but they’re questions that establishment Democratic Party leaders should have answered long ago—not just for the planet’s sake, but for the sake of the party’s political future. In the wake of devastating hurricane and wildfire seasons fueled by global warming, Democratic voters are more motivated by climate change than ever before. Ocasio-Cortez was perhaps more keenly aware of that than others: Her mostly-Latino constituency is more worried about climate change than other demographic groups, and her own grandfather died in Hurricane Maria. But if the party is still searching for lessons from her shocking win, she’s made one pretty clear: an aggressive, full thought-out, party-wide climate plan is long overdue.

No comments:

Post a Comment