The

Hughes H-4 Hercules is a prototype strategic airlift flying boat

designed and built by the ... He teamed with aircraft designer Howard Hughes to create what would become the largest aircraft built at that time. It was designed ..... Seaplanes & Flying Boats: A Timeless Collection from Aviation's Golden Age. New York: BCL ...

Hughes H-4 Hercules

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The

Hughes H-4 Hercules (also known as the "

Spruce Goose";

registration NX37602) is a prototype

strategic airlift flying boat designed and built by the

Hughes Aircraft Company. Intended as a

transatlantic flight transport for use during

World War II,

it was not completed in time to be used in the war. The aircraft made

only one brief flight on November 2, 1947, and the project never

advanced beyond the single example produced. Built from wood because of

wartime restrictions on the use of

aluminium and concerns about weight, it was nicknamed by critics the "Spruce Goose", although it was made almost entirely of

birch.

[2][3] The Hercules is the largest flying boat ever built and has the largest

wingspan of any aircraft in history.

[4] It remains in good condition and is on display at the

Evergreen Aviation & Space Museum in

McMinnville, Oregon,

United States.

[5]

Design and development

In 1942, the

U.S. War Department needed to transport war

materiel and personnel to Britain. Allied shipping in the Atlantic Ocean was

suffering heavy losses to German U-boats,

so a requirement was issued for an aircraft that could cross the

Atlantic with a large payload. Wartime priorities meant the aircraft

could not be made of strategic materials (e.g., aluminum).

[6]

The aircraft was the brainchild of

Henry J. Kaiser, a leading

Liberty ship builder. He teamed with aircraft designer

Howard Hughes

to create what would become the largest aircraft built at that time. It

was designed to carry 150,000 pounds, 750 fully equipped troops or two

30-ton

M4 Sherman tanks.

[7] The original designation "HK-1" reflected the Hughes and Kaiser collaboration.

[8]

The HK-1 contract was issued in 1942 as a development contract

[9] and called for three aircraft to be constructed in two years for the war effort.

[10]

Seven configurations were considered, including twin-hull and

single-hull designs with combinations of four, six, and eight

wing-mounted engines.

[11] The final design chosen was a behemoth, eclipsing any large transport then built.

[9][12][N 1] It would be built mostly of wood to conserve metal (its elevators and rudder were fabric-covered

[13]), and was nicknamed the "Spruce Goose" (a name Hughes hated) or the

Flying Lumberyard.

[14]

While Kaiser had originated the "flying cargo ship" concept, he did

not have an aeronautical background and deferred to Hughes and his

designer,

Glenn Odekirk.

[12] Development dragged on, which frustrated Kaiser, who blamed delays partly on restrictions placed for the acquisition of

strategic materials such as

aluminum, and partly on Hughes' insistence on "perfection".

[15]

Construction of the first HK-1 took place 16 months after the receipt

of the development contract. Kaiser then withdrew from the project.

[14][16]

Rearward view of the Hercules H-4's fuselage

Hughes continued the program on his own under the designation

"H-4 Hercules",

[N 2]

signing a new government contract that now limited production to one

example. Work proceeded slowly, and the H-4 was not completed until well

after the war was over. It was built by the

Hughes Aircraft Company at

Hughes Airport, location of present-day

Playa Vista, Los Angeles, California, employing the

plywood-and-resin "

Duramold" process

[13][N 3] – a form of composite technology – for the laminated wood construction, which was considered a technological

tour de force.

[8] The specialized wood veneer was made by Roddis Manufacturing in

Marshfield, Wisconsin. Hamilton Roddis had teams of young women ironing the (unusually thin) strong birch wood veneer before shipping to California.

[17]

A house moving company transported the airplane on streets to Pier E in

Long Beach, California.

They moved it in three large sections: the fuselage, each wing—and a

fourth, smaller shipment with tail assembly parts and other smaller

assemblies. After Hughes Aircraft completed final assembly, they erected

a hangar around the flying boat, with a ramp to launch the H-4 into the

harbor.

[2]

Howard Hughes was called to testify before the

Senate War Investigating Committee in 1947 over the use of government funds for the aircraft. During a

Senate hearing on August 6, 1947 (the first of a series of appearances), Hughes said:

The Hercules was a monumental undertaking. It is the largest aircraft

ever built. It is over five stories tall with a wingspan longer than a

football field. That's more than a city block. Now, I put the sweat of

my life into this thing. I have my reputation all rolled up in it and I

have stated several times that if it's a failure, I'll probably leave

this country and never come back. And I mean it.[18][N 4]

Operational history

During a break in the Senate hearings, Hughes returned to

California to run taxi tests on the H-4.

[13]

On November 2, 1947, the taxi tests began with Hughes at the controls.

His crew included Dave Grant as copilot, two flight engineers, Don Smith

and Joe Petrali, 16 mechanics, and two other flight crew. In addition,

the H-4 carried seven invited guests from the press corps and an

additional seven industry representatives. Thirty-six were on board.

[19]

After the first two taxi runs, four reporters left to file stories,

but the remaining press stayed for the final test run of the day.

[20]

After picking up speed on the channel facing Cabrillo Beach, the

Hercules lifted off, remaining airborne at 70 ft (21 m) off the water at

a speed of 135 miles per hour (217 km/h) for around a mile (1.6 km).

[21] At this altitude, the aircraft still experienced

ground effect.

[22]

The brief flight proved to detractors that Hughes' (now unneeded)

masterpiece was flight-worthy—thus vindicating the use of government

funds.

[23]

However, the Spruce Goose never flew again. Its lifting capacity and

ceiling were never tested. A full-time crew of 300 workers, all sworn to

secrecy, maintained the aircraft in flying condition in a

climate-controlled hangar. The company reduced the crew to 50 workers in

1962, and then disbanded it after Hughes' death in 1976.

[24]

Display

Hughes H-4 Hercules at Evergreen Aviation & Space Museum

In 1980, the Hercules was acquired by the Aero Club of Southern

California, which put the aircraft on display in a large dome adjacent

to the

Queen Mary exhibit in

Long Beach, California. In 1988,

The Walt Disney Company

acquired both attractions and the associated real estate. Disney

informed the Aero Club of Southern California that it no longer wished

to display the Hercules after its highly ambitious

Port Disney

was scrapped. After a long search for a suitable host, the Aero Club of

Southern California arranged for the Hughes flying boat to be given to

Evergreen Aviation Museum in exchange for payments and a percentage of the museum's profits.

[25] The aircraft was transported by

barge, train, and truck to its current home in

McMinnville, Oregon (about 40 miles (60 km) southwest of

Portland),

where it was reassembled by Contractors Cargo Company and is currently

on display. The aircraft arrived in McMinnville on February 27, 1993,

after a 138-day, 1,055-mile (1,698 km) trip from Long Beach. The dome is

now used by

Carnival Cruise Lines as its Long Beach terminal.

By the mid-1990s, the former Hughes Aircraft hangars at

Hughes Airport, including the one that held the Hercules, were converted into sound stages. Scenes from movies such as

Titanic,

What Women Want and

End of Days have been filmed in the 315,000-square-foot (29,000 m

2)

aircraft hangar where Howard Hughes created the flying boat. The hangar

will be preserved as a structure eligible for listing in the

National Register of Historic Buildings in what is today the large light industry and housing development in the

Playa Vista neighborhood of Los Angeles.

[26]

The

Western Museum of Flight in Torrance, California has a large collection of construction photographs and blueprints of the Hercules.

[citation needed]

Specifications (H-4)

Performance specifications are projected.

General characteristics

Performance

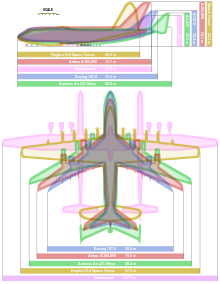

A size comparison between four of the largest aircraft:

Hughes H-4 Hercules (1947)

Notable appearances in media

See also

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Related lists

References

Notes

No comments:

Post a Comment