Lake Baikal

is rich in biodiversity. It hosts more than 1,000 species of plants and

2,500 species of animals based on current knowledge, but the actual

figures for ...

Lake Baikal

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Lake Baikal |

|

|

| Location |

Siberia, Russia |

| Coordinates |

53°30′N 108°0′ECoordinates: 53°30′N 108°0′ECoordinates:  53°30′N 108°0′E 53°30′N 108°0′E |

| Lake type |

Continental rift lake |

| Primary inflows |

Selenge, Barguzin, Upper Angara |

| Primary outflows |

Angara |

| Catchment area |

560,000 km2 (216,000 sq mi) |

| Basin countries |

Russia and Mongolia |

|

| Max. length |

636 km (395 mi) |

| Max. width |

79 km (49 mi) |

| Surface area |

31,722 km2 (12,248 sq mi)[1] |

| Average depth |

744.4 m (2,442 ft)[1] |

| Max. depth |

1,642 m (5,387 ft)[1] |

| Water volume |

23,615.39 km3 (5,700 cu mi)[1] |

| Residence time |

330 years[2] |

| Shore length1 |

2,100 km (1,300 mi) |

| Surface elevation |

455.5 m (1,494 ft) |

|

| Frozen |

January–May |

| Islands |

27 (Olkhon) |

| Settlements |

Irkutsk |

|

|

|

| Type |

Natural |

| Criteria |

vii, viii, ix, x |

| Designated |

1996 (22nd session) |

| Reference no. |

754 |

| State Party |

Russia Russia |

| Region |

Asia |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. |

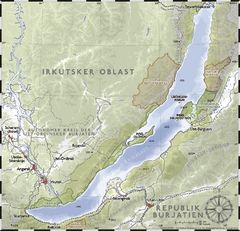

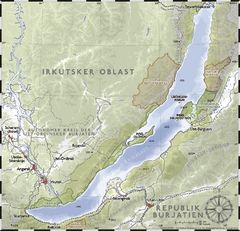

Lake Baikal (

Russian:

о́зеро Байка́л,

tr. Ozero Baykal;

IPA: [ˈozʲɪrə bɐjˈkɑl];

Buryat:

Байгал нуур,

Mongolian:

Байгал нуур,

Baygal nuur, etymologically meaning, in Mongolian, "the Nature Lake"

[3]) is a

rift lake in

Russia, located in southern

Siberia, between

Irkutsk Oblast to the northwest and the

Buryat Republic to the southeast.

Lake Baikal is the largest

freshwater lake by volume in the world, containing roughly 20% of the world's unfrozen surface fresh water.

[4][5] With a maximum depth of 1,642 m (5,387 ft),

[1] Baikal is the world's deepest lake.

[6] It is considered among the world's

clearest[7] lakes and is considered the world's oldest lake

[8] — at 25 million years.

[9] It is the

seventh-largest lake in the world by surface area. With 23,615.39 km

3 (5,700 cu mi) of fresh water,

[1] it contains more water than all the North American

Great Lakes combined.

[10]

Like

Lake Tanganyika, Lake Baikal was formed as an ancient

rift valley, having the typical long crescent shape with a surface area of 31,722 km

2

(12,248 sq mi). Baikal is home to thousands of species of plants and

animals, many of which exist nowhere else in the world. The lake was

declared a

UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996.

[11] It is also home to

Buryat tribes who reside on the eastern side of Lake Baikal,

[12][13] rearing goats, camels, cattle, and sheep,

[13] where the mean temperature varies from a winter minimum of −19 °C (−2 °F) to a summer maximum of 14 °C (57 °F).

[14]

Geography and hydrography

Lake Baikal is in a rift valley, created by the

Baikal Rift Zone, where the Earth's crust is slowly pulling apart.

[5]

At 636 km (395 mi) long and 79 km (49 mi) wide, Lake Baikal has the

largest surface area of any freshwater lake in Asia, at 31,722 km

2

(12,248 sq mi), and is the deepest lake in the world at 1,642 m

(5,387 ft). The bottom of the lake is 1,186.5 m (3,893 ft) below sea

level, but below this lies some 7 km (4.3 mi) of

sediment, placing the rift floor some 8–11 km (5.0–6.8 mi) below the surface: the deepest continental

rift on Earth.

[5]

In geological terms, the rift is young and active—it widens about 2 cm

(0.79 in) per year. The fault zone is also seismically active; hot

springs occur in the area and notable

earthquakes

happen every few years. The lake is divided into three basins: North,

Central, and South, with depths about 900 m (3,000 ft), 1,600 m

(5,200 ft), and 1,400 m (4,600 ft), respectively. Fault-controlled

accommodation zones rising to depths about 300 m (980 ft) separate the

basins. The North and Central basins are separated by

Academician Ridge,

while the area around the Selenga Delta and the Buguldeika Saddle

separates the Central and South basins. The lake drains into the

Angara tributary of the

Yenisei. Notable landforms include

Cape Ryty on Baikal's northwest coast.

Baikal's age is estimated at 25–30 million years, making it one of the most

ancient lakes in

geological history.

[citation needed] It is unique among large, high-latitude lakes, as its

sediments

have not been scoured by overriding continental ice sheets. Russian,

U.S., and Japanese cooperative studies of deep-drilling core sediments

in the 1990s provide a detailed record of climatic variation over the

past 6.7 million years.

[15][16]

Longer and deeper sediment cores are expected in the near future. Lake

Baikal is the only confined freshwater lake in which direct and indirect

evidence of

gas hydrates exists.

[17][18][19]

The lake is completely surrounded by mountains. The

Baikal Mountains on the north shore and the

taiga are technically protected as a national park. It contains 27 islands; the largest,

Olkhon,

is 72 km (45 mi) long and is the third-largest lake-bound island in the

world. The lake is fed by as many as 330 inflowing rivers.

[4] The main ones draining directly into Baikal are the

Selenga River, the

Barguzin River, the

Upper Angara River, the

Turka River, the

Sarma River, and the

Snezhnaya River. It is drained through a single outlet, the

Angara River.

Despite its great depth, the lake's waters are well-mixed and well-oxygenated throughout the water column, compared to the

stratification that occurs in such bodies of water as

Lake Tanganyika and the

Black Sea.

-

Lake Baikal as seen from the

OrbView-2 satellite

-

Spring ice melt underway on Lake Baikal

-

Circle of thin ice, diameter of 4.4 km (2.7 mi) at the lake's southern tip, probably caused by convection

-

-

Mountains seen from the banks of Baikal

Fauna and flora

Lake Baikal is rich in

biodiversity.

It hosts more than 1,000 species of plants and 2,500 species of animals

based on current knowledge, but the actual figures for both groups are

believed to be significantly higher.

[20][21] More than 80% of the animals are

endemic.

[21] The

Baikal seal or nerpa (

Pusa sibirica) is found throughout Lake Baikal.

[22] It is one of only three entirely

freshwater seal populations in the world, the other two being subspecies of

ringed seals.

The watershed of Lake Baikal has numerous floral species represented. The

marsh thistle,

Cirsium palustre, is found here at the eastern limit of its geographic range.

[23]

Fish

Two species of

grayling (

Thymallus baikalensis and

T. brevipinnis) are found only in Baikal and rivers that drain into the lake.

[24][25]

In total, fewer than 60 native fish species are in the lake, but more than half of these are endemic.

[20] The families

Abyssocottidae (deep-water sculpins),

Comephoridae (golomyankas or Baikal oilfish), and

Cottocomephoridae (Baikal sculpins) are entirely restricted to the lake

basin.

[20][26] All these are part of the

Cottoidea. Of particular note are the two species of

golomyanka (

Comephorus baicalensis and

C. dybowskii).

These long-finned, translucent fish typically live in open water in

depths of 100–500 m (330–1,640 ft), but occur both shallower and much

deeper. They are the primary prey of the Baikal seal and represent the

largest fish

biomass in the lake.

[27] Beyond members of Cottoidea, there are few endemic fish species in the lake.

[20]

The most important local species for fisheries is the

omul (

Coregonus migratorius), an endemic

whitefish.

[20] It is caught,

smoked, and then sold widely in markets around the lake. Also, a second endemic whitefish inhabits the lake,

C. baicalensis.

[28] The

Baikal black grayling (

Thymallus baicalensis),

Baikal white grayling (

T. brevipinnis), and

Baikal sturgeon (

Acipenser baerii baicalensis) are other important species with commercial value. They are also endemic to the Lake Baikal basin.

[24][25][29][30]

Invertebrates

The lake hosts a rich endemic fauna of invertebrates.

Epischura baikalensis is endemic to Lake Baikal and the dominating

zooplankton species there, making up 80 to 90% of total

biomass.

[31]

Among the most diverse invertebrate groups are the

turbellarian worms,

freshwater snails, and

amphipod crustaceans.

More than 350 species and subspecies of amphipods are endemic to the lake.

[21] They are exceptionally diverse in

ecology and appearance, ranging from the pelagic

Macrohectopus to the relatively large deep-water

Abyssogammarus and

Garjajewia, the tiny herbivorous

Micruropus, and the parasitic

Pachyschesis (parasitic on other amphipods).

[32]

The "gigantism" of some Baikal amphipods, which has been compared to

that seen in Antarctic amphipods, has been linked to the high level of

dissolved oxygen in the lake.

[33] Among the "giants" are several species of spiny

Acanthogammarus that are found at both shallow and large depths.

[34] These conspicuous and common amphipods are essentially carnivores (will also take

detritus), and can reach a body length up to 7 cm (2.8 in).

[32][34]

As of 2006, almost 150 freshwater snails are known from Lake Baikal, including 117 endemic species from the subfamilies

Baicaliinae (part of

Amnicolidae) and

Benedictiinae (part of

Lithoglyphidae), and the families

Planorbidae and

Valvatidae.

[35] All endemics have been recorded between 20 and 30 m (66 and 98 ft), but the majority mainly live at shallower depths.

[35] About 30 freshwater snail species can be seen deeper than 100 m (330 ft), which represents the approximate limit of the

sunlight zone, but only 10 are truly deepwater species.

[35] In general, Baikal snails are thin-shelled and small. Two of the most common species are

Benedictia baicalensis and

Megalovalvata baicalensis.

[36] Bivalve diversity is lower with more than 30 species; about half of these, all in the families

Euglesidae,

Pisidiidae, and

Sphaeriidae, are endemic (the only other family in the lake is

Unionidae with a single nonendemic species).

[36][37] The endemic bivalves are mainly found in shallows, with few species from deep water.

[38]

With almost 200 described species, including more than 160 endemics, the center of diversity for aquatic freshwater

oligochaetes is Lake Baikal.

[39] A smaller number of other freshwater

annelids are known: 13 species of

Hirudinea (leeches) and four

polychaetes.

[39] Several hundred species of

nematodes are known from the lake, but a large percentage of these are

undescribed.

[39]

At least 18 species of

sponges occur in the lake,

[40] including 14 species from the endemic family

Lubomirskiidae (the remaining are from the nonendemic family

Spongillidae).

[41] In the nearshore regions of Baikal, the largest

benthic biomass is sponges.

[40] Lubomirskia baicalensis,

Baikalospongia bacillifera, and

B. intermedia are unusually large for freshwater sponges and can reach 1 m (3.3 ft) or more.

[40][42] These three are also the most common sponges in the lake.

[40] Most sponges in the lake are typically green when alive because of

symbiotic chlorophytes (

zoochlorella), but can also be brownish or yellowish.

[43]

History

The Baikal area has a long history of human habitation. An early known tribe in the area was the

Kurykans, forefathers of two ethnic groups: the

Buryats; and the

Yakuts.

[citation needed]

Located in the former northern territory of the

Xiongnu confederation, Lake Baikal is one site of the

Han–Xiongnu War, where the armies of the

Han dynasty

pursued and defeated the Xiongnu forces from the 2nd century BC to the

1st century AD. They recorded that the lake was a "huge sea" (

hanhai) and designated it the North Sea (

Běihǎi) of the semimythical

Four Seas.

[44]

The Kurykans, a Siberian tribe who inhabited the area in the sixth

century, gave it a name that translates to "much water". Later on, it

was called "natural lake" (

Baygal nuur) by the

Buryats and "rich lake" (

Bay göl) by the

Yakuts.

[45] Little was known to Europeans about the lake until Russia expanded into the area in the 17th century. The first

Russian explorer to reach Lake Baikal was

Kurbat Ivanov in 1643.

[46]

Russian expansion into the Buryat area around Lake Baikal

[47] in 1628–58 was part of the

Russian conquest of Siberia. It was done first by following the Angara River upstream from

Yeniseysk

(founded 1619) and later by moving south from the Lena River. Russians

first heard of the Buryats in 1609 at Tomsk. According to folktales

related a century after the fact, in 1623,

Demid Pyanda, who may have been the first Russian to reach the Lena, crossed from the upper Lena to the Angara and arrived at Yeniseysk.

[48]

Vikhor Savin (1624) and

Maksim Perfilyev (1626 and 1627–28) explored

Tungus country on the lower Angara. To the west,

Krasnoyarsk on the upper Yenisei was founded in 1627. A number of ill-documented expeditions explored eastward from Krasnoyarsk. In 1628,

Pyotr Beketov first encountered a group of Buryats and collected

yasak from them at the future site of

Bratsk.

In 1629, Yakov Khripunov set off from Tomsk to find a rumored silver

mine. His men soon began plundering both Russians and natives. They were

joined by another band of rioters from Krasnoyarsk, but left the Buryat

country when they ran short of food. This made it difficult for other

Russians to enter the area. In 1631, Maksim Perfilyev built an

ostrog

at Bratsk. The pacification was moderately successful, but in 1634,

Bratsk was destroyed and its garrison killed. In 1635, Bratsk was

restored by a punitive expedition under Radukovskii. In 1638, it was

besieged unsuccessfully.

[citation needed]

In 1638, Perfilyev crossed from the Angara over the Ilim portage to the

Lena River and went downstream as far as

Olyokminsk. Returning, he sailed up the

Vitim River

into the area east of Lake Baikal (1640) where he heard reports of the

Amur country. In 1641, Verkholensk was founded on the upper Lena. In

1643,

Kurbat Ivanov went further up the Lena and became the first Russian to see Lake Baikal and

Olkhon Island. Half his party under Skorokhodov remained on the lake, reached the

Upper Angara at its northern tip, and wintered on the

Barguzin River on the northeast side.

[citation needed]

In 1644, Ivan Pokhabov went up the Angara to Baikal, becoming perhaps

the first Russian to use this route, which is difficult because of the

rapids. He crossed the lake and explored the lower

Selenge River. About 1647, he repeated the trip, obtained guides, and visited a 'Tsetsen Khan' near

Ulan Bator. In 1648, Ivan Galkin built an

ostrog

on the Barguzin River which became a center for eastward expansion. In

1652, Vasily Kolesnikov reported from Barguzin that one could reach the

Amur country by following the Selenga, Uda, and Khilok Rivers to the

future sites of

Chita and

Nerchinsk. In 1653,

Pyotr Beketov

took Kolesnikov's route to Lake Irgen west of Chita, and that winter

his man Urasov founded Nerchinsk. Next spring, he tried to occupy

Nerchensk, but was forced by his men to join

Stephanov on the Amur. Nerchinsk was destroyed by the local Tungus, but restored in 1658.

[citation needed]

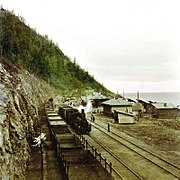

The

Trans-Siberian Railway was built between 1896 and 1902. Construction of the

scenic railway around the southwestern end of Lake Baikal required 200 bridges and 33 tunnels. Until its completion, a

train ferry transported railcars across the lake from

Port Baikal to

Mysovaya for a number of years. The lake became the site of the minor

engagement between the

Czechoslovak legion and the

Red Army

in 1918. At times during winter freezes, the lake could be crossed on

foot—though at risk of frostbite and deadly hypothermia from the cold

wind moving unobstructed across flat expanses of ice. In the winter of

1920, the

Great Siberian Ice March

occurred, when the retreating White Russian Army crossed frozen Lake

Baikal. The wind on the exposed lake was so cold, many people died,

freezing in place until spring thaw. Beginning in 1956, the impounding

of the

Irkutsk Dam on the Angara River raised the level of the lake by 1.4 m (4.6 ft).

[49]

As the railway was built, a large hydrogeographical expedition headed by

F.K. Drizhenko produced the first detailed contour map of the lake bed.

[8]

| Lake Baikal |

|

|

|

Russian map circa 1700, Baikal (not to scale) is at top.

|

|

|

|

Steam locomotive on the circum-Baikal railroad.

|

|

Research

Baikal fishermen fish for 15 commercially used species. The

omul, found only in Baikal, accounts for most of the catch.

[50]

Several organizations are carrying out natural research projects on

Lake Baikal. Most of them are governmental or associated with

governmental organizations. The

Baikalian Research Centre is an independent research organization carrying out environmental educational and research projects at Lake Baikal.

[51]

In July 2008, Russia sent two small

submersibles,

Mir-1 and

Mir-2,

to descend 1,592 m (5,223 ft) to the bottom of Lake Baikal to conduct

geological and biological tests on its unique ecosystem. Although

originally reported as being successful, they did not set a world record

for the deepest freshwater dive, reaching a depth of only 1,580 m

(5,180 ft).

[52] That record is currently held by

Anatoly Sagalevich, at 1,637 m (5,371 ft) (also in Lake Baikal aboard a Pisces submersible in 1990).

[52][53] Russian scientist and federal politician

Artur Chilingarov, the leader of the mission, took part in the Mir dives

[54] as did Russian leader

Vladimir Putin.

Since 1993,

neutrino research has been conducted at the

Baikal Deep Underwater Neutrino Telescope

(BDUNT). The Baikal Neutrino Telescope NT-200 is being deployed in Lake

Baikal, 3.6 km (2.2 mi) from shore at a depth of 1.1 km (0.68 mi). It

consists of 192 optical modules (OMs).

[55]

Economy

The lake, nicknamed "the Pearl of Siberia", drew investors from the

tourist industry as energy revenues sparked an economic boom.

[56] Viktor Grigorov's Grand Baikal in

Irkutsk

is one of the investors, who planned to build three hotels, creating

570 jobs. In 2007, the Russian government declared the Baikal region a

special economic zone. A popular resort in

Listvyanka

is home to the seven-story Hotel Mayak. At the northern part of the

lake, Baikalplan (a German NGO) built together with Russians in 2009 the

Frolikha Adventure Coastline Track, a 100 km (62 mi)-long

long-distance trail as example for a sustainable development of the region. Baikal was also declared a

UNESCO World Heritage site in 1996.

Rosatom plans to build a laboratory near Baikal, in conjunction with an international

uranium plant and to invest $2.5 billion in the region and create 2,000 jobs in the city of

Angarsk.

[56]

| Tourism industry on Lake Baikal |

|

|

|

Recreational boaters on Chivyrkuisky Bay

|

|

|

|

Sportfishing boats on Lake Baikal

|

|

Lake Baikal is a popular destination among tourists from all over the

world. According to Russian Federal State Statistics Service, in 2013

79,179 foreign tourists visited Irkutsk and lake Baikal; in 2014 -

146,937 visitors. The most popular places to stay by the lake are

Listvyanka village,

Olkhon island,

Kotelnikovsky cape, Baykalskiy Priboi and Turka village. The popularity

of lake Baikal is growing from year to year, but there are no developed

infrastructure in the area. For the quality of service and comfort for

the visitors point of view, Lake Baikal still has a long way to go.

Environmental concerns

Baykalsk Pulp and Paper Mill

Baykalsk Pulp and Paper Mill

The

Baykalsk Pulp and Paper Mill was constructed in 1966, directly on the shoreline, bleaching paper with

chlorine and discharging waste into Baikal. After decades of protest, the plant was closed in November 2008 due to unprofitability.

[57][58] In March 2009, the plant owner announced the paper mill would never reopen.

[59] However, on 4 January 2010, the production was resumed. On 13 January 2010,

Vladimir Putin

introduced changes in the legislation legalising the operation of the

mill, which brought about a wave of protests of ecologists and local

residents.

[60]

This was based on Putin's visual verification from a minisubmarine, "I

could see with my own eyes — and scientists can confirm — Baikal is in

good condition and there is practically no pollution".

[61]

In September 2013, the mill underwent a final bankruptcy, with the last

800 workers slated to lose their jobs by 28 December 2013.

[62]

On 28 December 2013 the Russian Government decided to build a Russian

Nature Reserves Expo Center on the place of the paper mill.

[63]

Planned East Siberia-Pacific Ocean oil pipeline

The lake in the winter, as seen from the tourist resort of

Listvyanka: The ice is thick enough to support pedestrians and snowmobiles.

Russian oil pipelines state company

Transneft[64]

was planning to build a trunk pipeline that would have come within

800 m (2,600 ft) of the lake shore in a zone of substantial seismic

activity. Environmental activists in Russia,

[65] Greenpeace, Baikal pipeline opposition

[66] and local citizens

[67]

were strongly opposed to these plans, due to the possibility of an

accidental oil spill that might cause significant damage to the

environment. According to the Transneft's president, numerous meetings

with citizens near the lake were held in towns along the route,

especially in

Irkutsk.

[68] However, it was not until Russian president

Vladimir Putin

ordered the company to consider an alternative route 40 kilometers

(25 mi) to the north to avoid such ecological risks that Transneft

agreed to alter its plans.

[69]

Transneft has since decided to move the pipeline away from Lake Baikal,

so that it will not pass through any federal or republic natural

reserves.

[70][71] Work began on the pipeline, two days after President Putin agreed to changing the route away from Lake Baikal.

[72]

Proposed nuclear plant

In 2006, the Russian government announced plans to build the world's

first International Uranium Enrichment Centre at an existing nuclear

facility in Angarsk, 95 km (59 mi) from the lake's shores. However,

critics and environmentalists argue it would be a disaster for the

region and are urging the government to reconsider.

[73]

After enrichment, only 10% of the uranium-derived radioactive material would be exported to international customers,

[73] leaving 90% near the Lake Baikal region for storage.

Uranium tailings

contain radioactive and toxic materials, which if improperly stored,

are potentially dangerous to humans and can contaminate rivers and

lakes.

[73]

Other pollution sources

According to

The Moscow Times and

Vice_(magazine), an increasing amount of an

invasive species of

algae

thrives in the lake from hundreds of tons of liquid waste, including

fuel and excrement, regularly disposed into the lake by tourist sites,

and up to 25,000 tons of liquid waste disposed every year by local

ships.

[74] [75]

Historical traditions

An 1883 British map using the More Baikal (Baikal Sea) designation, rather than the conventional Ozero Baikal (Lake Baikal)

The first European to reach the lake is said to have been

Kurbat Ivanov in 1643.

[76]

In the past, the Baikal was referred to by many Russians as the "Baikal Sea" (

Russian:

Море Байкал,

More Baikal), rather than merely "Lake Baikal" (

Russian:

Озеро Байкал,

Ozero Baikal).

[77] This usage is attested already in the

Life of

Protopope Avvakum (1621–1682),

[78] and on the late-17th-century maps by

Semyon Remezov.

[79] It is also attested in the famous song, now passed into the tradition, that opens with the words

Славное море, священный Байкал (Glorious sea, [the] sacred Bajkal). To this day, the strait between the western shore of the Lake and the

Olkhon Island is called

Maloye More (Малое Море), i.e. "the

Little Sea".

Lake Baikal is nicknamed "Older sister of Sister Lakes (

Lake Khövsgöl and Lake Baikal)".

[citation needed]

According to 19th-century traveler T. W. Atkinson, locals in the Lake

Baikal Region had the tradition that Christ visited the area:

The people have a tradition in connection with this region which they

implicitly believe. They say "that Christ visited this part of Asia and

ascended this summit, whence he looked down on all the region around.

After blessing the country to the northward, he turned towards the

south, and looking across the Baikal, he waved his hand, exclaiming

'Beyond this there is nothing.'" Thus they account for the sterility of Daouria, where it is said "no corn will grow."[80]

Lake Baikal has been celebrated in several Russian folk songs. Two of

these songs are well known in Russia and its neighboring countries,

such as Japan.

- "The Glorious Sea – Sacred Baikal" (in Russian: Славное Mope, Священный Байкал) is about a katorga fugitive. The lyrics as documented and edited in the 19th century by Dmitriy P. Davydov (1811–1888).[81] See "Barguzin River" for sample lyrics.

- "The Wanderer" (in Russian: Бродяга) is about a convict who had escaped from jail and was attempting to return home from Transbaikal.[82] The lyrics were collected and edited in the 20th century by Ivan Kondratyev.

The latter song was a secondary

theme song for the

Soviet Union's second color film,

Ballad of Siberia (1947; in

Russian:

Сказание о земле Сибирской).

Gallery

-

-

-

Icebound shore of Baikal in early April, at

Listvyanka

-

-

Late 19th-century steam icebreaker Baikal in port

-

-

-

References

Russia

Russia

No comments:

Post a Comment