begin quote from:

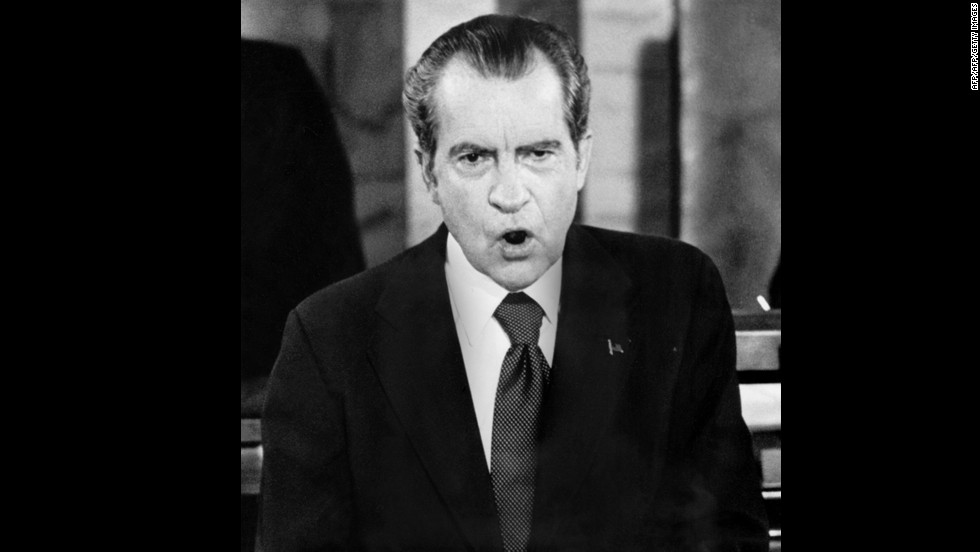

Woodward and Bernstein: Trump's Russia response is 'eerily similar' to Nixon's before the Saturday night massacre

Woodward and Bernstein: Trump's Russia response 'eerily similar' to Nixon's leading up to Saturday Night Massacre

Updated 10:44 AM ET, Sat February 10, 2018

Woodward and Bernstein adapted this piece from their 1976 book, "The Final Days." This excerpt is appearing both in The Washington Post and on CNN.

(CNN)We're

here again. A powerful and determined President is squaring off against

an independent investigator operating inside the Justice Department.

Special counsel Robert Mueller's mission is a comprehensive look at

Russian meddling in the 2016 election -- and any other crimes he

uncovers in the process. President Donald Trump insists it's all a

"witch hunt" and an unfair examination of his family's personal

finances. He constantly complains about the investigation in private and

reportedly asked his White House counsel to have Mueller fired. No

wonder many people are making comparisons to the Saturday Night Massacre

of 1973, when President Richard Nixon fired special prosecutor

Archibald Cox, and Attorney General Elliot Richardson and Deputy

Attorney General William Ruckelshaus resigned.

We

covered that eerily similar confrontation for The Washington Post 45

years ago. Nixon didn't know it at the time, but the Saturday Night

Massacre would become a pivot point in his presidency -- crucial to the

charge that he'd obstructed justice. For him, the consequences were

terminal. A retelling of the episode, adapted from "The Final Days," as

we called our book on the president's last year, can illuminate the

stakes.

• • •

In

April 1973, Nixon persuaded Richardson, his defense secretary, to

switch departments and become the attorney general. The president

invited him to a Camp David meeting that turned out to be part of the

Watergate cover-up: He wanted to ensure that Richardson would be an ally

in a new Watergate investigation.

Richardson's

chilly, formal manner evoked the Eastern, academic establishment that

Nixon despised. The slow, winding rhetoric that weighed down his

conversation drove the president to distraction. Still, he needed

Richardson, with his impeccable reputation, to redeem his Justice

Department and take charge of the Watergate investigation.

Nixon

told him that the investigation must be thorough and complete, though

there might be some areas of national security that would have to be

left alone. "You must pursue this investigation even if it leads to the

president," Nixon said, and his eyes met Richardson's. "I'm innocent.

You've got to believe I'm innocent. If you don't, don't take the job."

Vastly

relieved, Richardson nodded his acceptance: Nixon, he thought, would

never set such an investigation in motion unless he was innocent.

"The important thing is the presidency," Nixon continued. "If need be, save the presidency from the president."

Richardson, writing on a legal pad, paraphrased the thought: "If the monster is me, save the country."

Almost

immediately he appointed his old Harvard law professor, Archibald Cox

-- who had served as President John F. Kennedy's solicitor general -- as

special prosecutor to handle Watergate, promising him full

independence. Cox set about investigating, and three months later he

subpoenaed nine of the White House tapes.

Nixon

did not take kindly to this. White House chief of staff Alexander Haig

warned Richardson that the president might fire Cox if he weren't reined

in, shaking Richardson's faith in the president's innocence. "If we

have to have a confrontation, we will have it," Haig told him.

A

few days later, Haig said he had advised the president to turn over the

tapes, but Nixon had refused. The president would resign first. Haig

told Richardson he didn't know whether the president was hiding

something or whether he was merely concerned about the principle of

confidentiality, but he had never seen Nixon so worked up. "It makes you

wonder what must be on those tapes," said Haig, who himself was only a

few months into the job.

For

now, Richardson decided to give Nixon the benefit of the doubt while he

oversaw his department's investigation of Vice President Spiro Agnew,

who had been accepting illegal cash payoffs from contractors for years,

starting when he was a Maryland official.

In

October, Richardson was leaving an Oval Office briefing about the Agnew

situation when Nixon called after him. "Now that we have disposed of

that matter, we can go ahead and get rid of Cox." Richardson didn't know

how to take the remark. But soon the issue would come to a head.

• • •

On

Monday, October 15, the United States Court of Appeals for the District

of Columbia ruled that the president, who had fought the order to turn

over the nine subpoenaed tapes, must hand them over -- unless the White

House could reach "some agreement with the Special Prosecutor" out of

court. Nixon had until midnight Friday to comply, to appeal to the

Supreme Court or to reach a compromise with Cox. Richardson was doubtful

that the White House and Cox could agree on much of anything in five

days.

After the court decision came

down, Haig and White House lawyer J. Fred Buzhardt summoned Richardson.

They presented the attorney general with a plan: Nixon would personally

listen to the subpoenaed recordings and supervise the preparation of

transcripts that would be turned over to the court as a substitute for

the tapes. Cox -- long a bone in Nixon's throat and a bad idea in the

first place -- would be fired. And there would be no more litigating

over other tapes.

Richardson,

outwardly calm, raised an objection. The plan was contrary to the

agreement he had made with the Senate Judiciary Committee during his

confirmation hearings. He had promised that the special prosecutor could

be removed only for "extraordinary improprieties." If he were ordered

to fire Cox, he might instead have to resign himself.

Haig

and Buzhardt held their ground. Cox would have to go. Richardson left

the White House bewildered and uncertain of what would happen next.

Haig

called him 40 minutes later to suggest a compromise: Sen. John C.

Stennis, the 72-year-old Mississippi Democrat who chaired the Senate

Armed Services Committee, would be asked to make a comparison between

the transcripts and the tapes. His authenticated version would be

submitted to the court. (No mention was made of the fact that the

senator was partially deaf and that the tapes were difficult to hear

under the best of circumstances.) If Richardson accepted, Cox would not

have to be fired, but Richardson would forbid any further demands for

tapes. The president, Haig added, would expect Richardson's support if

it came to a showdown with Cox.

Later

that day, Richardson called Haig back and made it clear that he was

committed only to the Stennis authentication of the nine subpoenaed

tapes. He couldn't make any other promises.

Now

Richardson had to sell the Stennis compromise to Cox, who wanted to see

the terms in writing. Richardson drafted an agreement that said it

would "cover only the tapes heretofore subpoenaed by the Watergate grand

jury at the request of the Special Prosecutor." When he sent it to the

White House on Wednesday morning, October 17, Buzhardt cut that section.

The president, he knew, didn't ever want to hear about future requests

for tapes. The White House also wanted to empower Stennis to "paraphrase

language whose use in its original form would in his judgment be

embarrassing to the President."

Richardson

wanted to avoid a confrontation with Nixon, and he acquiesced. But Cox

flatly rejected the compromise. "The public cannot fairly be asked to

confide so difficult and responsible a task to any one man operating in

secrecy, consulting only with the White House," he wrote to the attorney

general on Thursday afternoon. And Cox wanted an agreement that would

"serve the function of a court decision in establishing the Special

Prosecutor's entitlement to other evidence." A court might want the

actual tapes, the best evidence, for any trial.

Richardson

took Cox's memo to a 6 p.m. meeting at the White House. Haig was

unaccepting. The White House was seeking a compromise, he said, and Cox

was making it impossible. He should be fired, Haig said. Three other

Nixon lawyers in the meeting agreed. They were confident that the

president could convince the public he'd acted reasonably.

Richardson

did not think so. He made it clear that he could live with Cox's

voluntary resignation but that he could not fire him for refusing the

Stennis plan.

Later that night,

Richardson sat in his study in McLean, Virginia. The rush of the Potomac

River was barely audible in the distance. He wrote at the top of a

yellow legal pad: "Why I Must Resign." He was sure that Cox could not be

persuaded to acquiesce, and he knew that the president wanted Cox out.

Richardson's

first reason for resigning was his promise to the Senate to guarantee

the independence of the special prosecutor. Second, he wrote that Cox

was being required to accept less than he had won in two court

decisions. "While Cox has rejected a proposal I consider reasonable, his

rejection of it cannot be regarded" as grounds for his removal. The

next morning Richardson planned to make that clear to the president.

But

that night, Nixon was drawing his own red lines. Even if Richardson was

on his side, the Stennis deal was not sufficient if it didn't block

future demands for tapes. Buzhardt wanted him to leave it alone -- the

Stennis compromise for now would be a giant step toward the end of

Watergate.

Eventually, Nixon blew up at him. "No," the president said. "No, period!"

Buzhardt

had been sure he could maneuver Cox into a position where the special

prosecutor would have to resign, since the White House and Richardson

would be lined up against him. But to do it, he needed some negotiating

room. The president had just denied him exactly that. By asserting that

the special prosecutor could not subpoena additional evidence, they were

laying credible grounds for Cox's defiance -- instead of his

resignation. And they were probably throwing Richardson into Cox's arms.

Now a showdown was inevitable.

• • •

Early

the next morning, Friday, October 19, Richardson had "Why I Must

Resign" typed and put it in his pocket. He called Haig and asked to see

the president. But when Richardson arrived at about 10 a.m., Haig had a

new deal. "Suppose we go ahead with the Stennis plan without firing

Cox," he said. Instead, they would persuade the appeals court to accept

the transcripts instead of the tapes, allowing use of the Stennis

compromise without Cox's assent. Perhaps the Senate Watergate Committee

would also accept transcripts.

Richardson

was taken aback. That would be fine, he said, thinking to himself that

he wouldn't have to resign, either. Haig said he would try to persuade

the president.

Richardson was in

for another surprise when he learned at the meeting that White House

lawyers had asked Cox "not to subpoena any other White House tape, paper

or document." Obviously, the special prosecutor could not accept that,

and this had not been part of the proposal Richardson had submitted to

Cox. Buzhardt said the president had forced them to add this new

condition the previous night.

Haig

left his office and came back soon to announce that Nixon had agreed to

keep Cox. It had been "bloody, bloody," Haig said. "I pushed so hard

that my usefulness to the president may be over."

Richardson

tried to add things up in his own mind. The Stennis compromise had a

new element: no future access. He was willing to accept it -- barely.

Cox could resign or keep his job, as he chose, and Richardson would not

have to fire him. Negotiations could continue. Richardson's reasons for

quitting, neatly typed, stayed folded in his pocket. Now Haig thought he

had Richardson on board.

Buzhardt

said that the next problem was how to contain Cox. Couldn't Richardson

simply order him not to go to court again for tapes? Cox would probably

resign, but nobody appeared particularly concerned by that prospect.

Richardson left the meeting, sure that there would be further discussion

before any such orders were issued to Cox.

Back

at his office, Richardson reviewed the White House meeting with his

aides. They had expected him to resign, and they were not convinced that

he could permit a restriction on Cox's future access without violating

his agreement with the Senate. So Richardson called back Haig and then

Buzhardt, insisting that the question of future access must not be

linked to the Stennis plan. They promised to take up the question with

the president again. Richardson relaxed, sure that he had avoided the

immediate bind.

But the president

was immovable. Whatever solution was arrived at, it had to solve the

problem of the tapes once and for all, he told Buzhardt and Haig.

At

7 p.m., Haig called Richardson to read him a letter from the president

that, he said, was on its way to him: "I am instructing you to direct

Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox of the Watergate Special Prosecution

Force that he is to make no further attempts by judicial process to

obtain tapes, notes or memoranda of Presidential conversations."

Richardson

was distressed that he had not been consulted. Haig said he had done

his best. He had twice tried to make Richardson's position clear to the

president. He had failed. Richardson took care to avoid saying whether

he would issue the order.

But after

Haig hung up, Nixon aides decided to announce the order through a White

House news release, thus eliminating Richardson as intermediary. The

order, in the president's name, was made directly to Cox, "as an

employee of the executive branch."

This

was too much for Richardson. "I will not do what the White House asks

of me," he told another Nixon aide. "I've never been so shabbily treated

in my life." He began drawing up his own press statement.

Haig

called him and persuaded him to calm down. Prominent members of both

parties were favorably disposed toward the compromise, he pointed out.

Richardson

let one more opportunity for confrontation pass. He did not like

bloodletting. He thanked Haig for his call. Richardson had negotiated

Agnew's resignation, and he felt he could once again avert a national

trauma.

But Cox was now faced with

an order from the president to abstain from seeking more tapes. In fact,

Cox was getting no tapes -- merely transcripts. He reasoned that he had

the court, the law and the attorney general on his side. He announced

that he would have a news conference early the next afternoon, Saturday,

October 20.

Buzhardt expected Cox

would announce his resignation. That will be tough, he thought to

himself, but the president can weather it. Yet when Cox stepped before

the cameras, he said he would continue pressing in court for the tapes.

He might be compelled to ask that Nixon be held in contempt if the White

House refused to turn them over.

Still,

Cox acknowledged the obvious: "Now, eventually a president can always

work his will," he said. "You remember when Andrew Jackson wanted to

take the deposits from the Bank of the United States and his secretary

of the treasury wouldn't do it. He fired him and then he appointed a new

secretary of the treasury, and he wouldn't do it, and he fired him. And

finally he got a third who would. That's one way of proceeding."

• • •

To

Nixon, this was the ultimate defiance. He had issued a clear order to

Cox, who was an employee of the executive branch. The president needed

to show that he was in control. He told Haig to have Cox fired.

Haig

called Richardson and ordered him to fire Cox. He was pretty sure

Richardson wouldn't do it. As expected, Richardson replied that he

wanted to see the president, to submit his resignation. In the

midafternoon he went to the White House, and Haig started working him

over: He must not resign now. Fire Cox, wait a week, and then resign.

"What

do you want me to do," Richardson asked sarcastically, "write a letter

of resignation, get it notarized to prove I wrote it today, and let it

surface in a week?"

"That's not a bad idea," Haig replied matter-of-factly.

"I want to see the president," Richardson said.

He

walked into the Oval Office at 4:30 p.m., and immediately Nixon urged

him to delay. Nixon knew that firing Cox would invite a move to impeach.

Richardson

said he could not. He was thinking to himself that this was the worst

moment in all his years of service in government. He was standing there,

refusing an urgent demand of the president of the United States. He had

considered himself a team player.

"I'm

sorry you feel that you have to act on your commitment to Cox and his

independence," the president said, "and not the larger public interest."

There

was a flash of anger. "Maybe," Richardson replied hotly, "your

perception and my perception of the public interest differ."

That was the end.

Deputy

Attorney General William D. Ruckelshaus was now the acting attorney

general. Haig phoned him, painting a picture of cataclysm if Ruckelshaus

did not fire Cox. "As you probably know," he said, "Elliot Richardson

feels he cannot execute the orders of the President."

"That is right, I know that."

"Are you prepared to do so?"

"No."

"Well, you know what it means when an order comes down from the commander in chief and a member of his team cannot execute it."

"That is right."

Haig thought Ruckelshaus was fired. Ruckelshaus presumed he had resigned.

At

about 6 p.m., Solicitor General Robert Bork, the third in command at

the Justice Department, accepted the order and signed the White House

draft of a two-paragraph letter firing Cox. At 8:22 p.m., White House

press secretary Ron Ziegler announced this news, adding that, further,

"the office of the Watergate Special Prosecution Force has been

abolished as of approximately 8 p.m."

After

9 p.m., Haig sent FBI officers to seal off the offices of Richardson,

Ruckelshaus and Cox to prevent any files from being removed.

The

television networks offered hourlong specials. The newspapers carried

banner headlines. Within two days, 150,000 telegrams had arrived in the

capital, the largest concentrated volume in the history of Western

Union. Deans of the most prestigious law schools in the country demanded

that Congress commence an impeachment inquiry.

By

the following Tuesday, 44 separate Watergate-related bills had been

introduced in the House. Twenty-two called for an impeachment

investigation.

• • •

Soon

thereafter, Nixon made two fateful miscalculations: He appointed

another special prosecutor to replace Cox, and he turned over an initial

batch of tapes, including one that vividly incriminated him. The

Trump-Mueller history is yet to be written.

No comments:

Post a Comment