Perth in Western Australia could become the world’s first ghost metropolis

Perth

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Perth, Western Australia)

This article is about the capital of Western Australia. For the city in Scotland, see Perth, Scotland. For other uses, see Perth (disambiguation).

Not to be confused with Perth (suburb) or City of Perth (local government area).

| Perth Western Australia |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Perth's skyline, viewed from South Perth.

|

|||||||

| Coordinates | 31°57′8″S 115°51′32″ECoordinates: 31°57′8″S 115°51′32″E | ||||||

| Population | 2,021,200 (2014)[1] (4th) | ||||||

| • Density | 310/km2 (800/sq mi) [2] | ||||||

| Established | 1829 | ||||||

| Area | 6,417.9 km2 (2,478.0 sq mi)(GCCSA)[3] | ||||||

| Time zone | AWST (UTC+8) | ||||||

| Location | |||||||

| State electorate(s) | Perth (and 41 others)[8] | ||||||

| Federal Division(s) | Perth (and 10 others) | ||||||

|

|||||||

Perth was originally founded by Captain James Stirling in 1829 as the administrative centre of the Swan River Colony. It gained city status (currently vested in the smaller City of Perth) in 1856, and was promoted to the status of a Lord Mayorality in 1929.[9] The city is named after Perth, Scotland, due to the influence of Sir George Murray, Member of Parliament for Perthshire and Secretary of State for War and the Colonies. The city's population increased substantially as a result of the Western Australian gold rushes in the late 19th century, largely as a result of emigration from the eastern colonies of Australia. During Australia's involvement in World War II, Fremantle served as a base for submarines operating in the Pacific Theatre, and a US Navy Catalina flying boat fleet was based at Matilda Bay.[10] An influx of immigrants after the war, predominantly from Britain, Greece, Italy and Yugoslavia, led to rapid population growth. This was followed by a surge in economic activity flowing from several mining booms in the late 20th and early 21st centuries that saw Perth become the regional headquarters for a number of large mining operations located around the state.

As part of Perth's role as the capital of Western Australia, the state's Parliament and Supreme Court are located within the city, as is Government House, the residence of the Governor of Western Australia. Perth became known worldwide as the "City of Light" when city residents lit their house lights and streetlights as American astronaut John Glenn passed overhead while orbiting the earth on Friendship 7 in 1962.[11][12] The city repeated the act as Glenn passed overhead on the Space Shuttle in 1998.[13][14] Perth came 8th in the Economist Intelligence Unit's August 2015 list of the world's most liveable cities,[15] and was classified by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network in 2010 as a world city.[16]

Contents

History

Main article: History of Perth, Western Australia

Indigenous history

Before European colonisation, the area had been inhabited by the Whadjuk Noongar people for over 40,000 years, as evidenced by archaeological findings on the Upper Swan River.[17] These Noongar people occupied the southwest corner of Western Australia and lived as hunter-gatherers. The wetlands on the Swan Coastal Plain were particularly important to them, both spiritually, featuring in local mythology, and as a source of food. Rottnest, Carnac and Garden Islands were also important to the Noongar people.[citation needed]The area where Perth now stands is also known as Boorloo by the Noongar people. Boorloo formed part of Mooro, the tribal lands of Yellagonga's group, one of several based around the Swan River and known collectively as the Whadjuk. The Whadjuk were part of a larger group of fourteen tribes that formed the south-west socio-linguistic block known as the Noongar (meaning "the people" in their language), also sometimes called the Bibbulmun.[18] On 19 September 2006, the Federal Court of Australia brought down a judgment recognising Noongar native title over the Perth metropolitan area, in the case of Bennell v State of Western Australia [2006] FCA 1243.[19] The judgment was overturned on appeal.[20]

Early European sightings

The first documented sighting of the region was made by the Dutch Captain Willem de Vlamingh and his crew on 10 January 1697.[21] Subsequent sightings between this date and 1829 were made by other Europeans, but as in the case of the sighting and observations made by Vlamingh, the area was considered to be inhospitable and unsuitable for the agriculture that would be needed to sustain a settlement.[22]Swan River Colony

Main article: Swan River Colony

The Foundation of Perth 1829 by George Pitt Morison is a historically accurate reconstruction of the official ceremony by which Perth was founded.

On 4 June 1829, newly arriving British colonists had their first view of the mainland, and Western Australia's founding has since been recognised by a public holiday on the first Monday in June each year. Captain James Stirling, aboard Parmelia, said that Perth was "as beautiful as anything of this kind I had ever witnessed". On 12 August that year, Helen Dance, wife of the captain of the second ship, Sulphur, cut down a tree to mark the founding of the town.

It is clear that Stirling had already selected the name Perth for the capital well before the town was proclaimed, as his proclamation of the colony, read in Fremantle on 18 June 1829, ended "given under my hand and Seal at Perth this 18th Day of June 1829. James Stirling Lieutenant Governor".[24] The only contemporary information on the source of the name comes from Fremantle's diary entry for 12 August, which records that they "named the town Perth according to the wishes of Sir George Murray".[25] Murray was born in Perth, Scotland, and was in 1829 Secretary of State for the Colonies and Member for Perthshire in the British House of Commons. The town was named after the Scottish Perth,[26] in Murray's honour.[27][28][29]

Beginning in 1831, hostile encounters between the British settlers and the Noongar people – both large-scale land users with conflicting land value systems – increased considerably as the colony grew. The hostile encounters between the two groups of people resulted in a number of events, including the execution of the Whadjuk elder Midgegooroo, the death of his son Yagan in 1833, and the Pinjarra massacre in 1834.

The racial relations between the Noongar people and the Europeans were strained due to these happenings. Because of the large amount of building in and around Boorloo, the local Whadjuk Noongar people were slowly dispossessed of their country. They were forced to camp around prescribed areas, including the swamps and lakes north of the settlement area including Third Swamp, known to them as Boodjamooling. Boodjamooling continued to be a main camp-site for the remaining Noongar people in the Perth region, and was also used by travellers, itinerants, and homeless people. By the gold-rush days of the 1890s they were joined by miners who were en route to the goldfields.[30]

In 1850, Western Australia was opened to convicts at the request of farming and business people looking for cheap labour.[31] Queen Victoria announced the city status of Perth in 1856.[32]

Federation and beyond

Perth looking across the Perth train station c. 1955

In 1933, Western Australia voted in a referendum to leave the Australian Federation, with a majority of two to one in favour of secession.[33] However, an election held shortly before the referendum had voted out the incumbent "pro-independence" government, replacing it with a government that did not support the independence movement. Respecting the result of the referendum, the new government nonetheless petitioned the Agent General of the United Kingdom for independence, where the request was simply ignored.[35]

City skyline from Kings Park

Geography

Central business district

Main article: Perth (suburb)

The central business district of Perth is bounded by the Swan River to the south and east, with Kings Park on the western end, while the railway reserve formed a northern border. A state and federally funded project named Perth City Link sunk a section of the railway line, to link Northbridge and the CBD for the first time in 100 years. The Perth Arena is a building in the city link area that has received a number of architecture awards.[which?] St Georges Terrace is the prominent street of the area with 1.3 million m2 of office space in the CBD.[39] Hay Street and Murray Street have most of the retail and entertainment facilities. The tallest building in the city is Central Park, which is the seventh tallest building in Australia.[40]

The CBD has recently been the centre of a mining-induced boom, with

several commercial and residential projects being built, including Brookfield Place, a 244 m (801 ft) office building for Anglo-Australian mining company BHP Billiton.

Perth skyline, viewed from Mill Point

Geology and landforms

Perth is set on the Swan River, named for the native black swans by Willem de Vlamingh, captain of a Dutch expedition and namer of WA's Rottnest Island who discovered the birds while exploring the area in 1697.[41] Traditionally, this water body had been known by Aboriginal inhabitants as Derbarl Yerrigan.[42] The city centre and most of the suburbs are located on the sandy and relatively flat Swan Coastal Plain, which lies between the Darling Scarp and the Indian Ocean. The soils of this area are quite infertile. The metropolitan area extends along the coast to Two Rocks in the north and Singleton to the south,[43] a total distance of approximately 125 kilometres (78 mi).[44] From the coast in the west to Mundaring in the east is a total distance of approximately 50 kilometres (31 mi). The Perth metropolitan area covers 6,418 square kilometres (2,478 sq mi).[3]

Satellite image of Perth

To the east, the city is bordered by a low escarpment called the Darling Scarp. Perth is on generally flat, rolling land – largely due to the high amount of sandy soils and deep bedrock. The Perth metropolitan area has two major river systems: the first is made up of the Swan and Canning Rivers; the second is that of the Serpentine and Murray Rivers, which discharge into the Peel Inlet at Mandurah.

Climate

Perth receives moderate though highly seasonal rainfall, making it the fourth wettest Australian capital city after Darwin, Sydney and Brisbane. Summers are generally very hot and dry, lasting from December to late March, with February generally being the hottest month of the year. Winters are relatively mild and wet, making Perth a classic example of a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa).[46][47] Perth is a particularly sunny city for this type of climate; it has an average of 8.8 hours of sunshine per day, which equates to around 3200 hours of annual sunshine, and 138.7 clear days annually, making it the sunniest capital city in Australia.[48]Summer is not completely devoid of rain and humidity, with sporadic rainfall in the form of short-lived thunderstorms, weak cold fronts and on occasions decaying tropical cyclones from Western Australia's north-west, which can bring significant rainfall. Winters are also known to be clear and sunny. The highest temperature recorded in Perth was 46.2 °C (115.2 °F) on 23 February 1991, although Perth Airport recorded 46.7 °C (116.1 °F) on the same day.[48][49] On most summer afternoons a sea breeze, known locally as the "Fremantle Doctor", blows from the southwest, providing relief from the hot north-easterly winds. Temperatures often fall below 30 °C (86 °F) a few hours after the arrival of the wind change.[50] In the summer, the 3 pm dewpoint averages at around 12 °C (54 °F).[48]

Winters are wet but mild, with most of Perth's annual rainfall being between May and September. The lowest temperature recorded in Perth was −0.7 °C (30.7 °F) on 17 June 2006.[49] The lowest temperature within the Perth metropolitan area was −3.4 °C (25.9 °F) on the same day at Jandakot Airport. However, temperatures at or below zero are very rare occurrences and it seldom gets cold enough for frost to form.[51]

The rainfall pattern has changed in Perth and southwest Western Australia since the mid-1970s. A significant reduction in winter rainfall has been observed with a greater number of extreme rainfall events in the summer months,[52] such as the slow-moving storms on 8 February 1992 that brought 120.6 millimetres (4.75 in) of rain, the highest recorded in Perth,[49][50] and a severe thunderstorm on 22 March 2010, which brought 40.2 millimetres (1.58 in) of rain and caused significant damage in the metropolitan area.[53]

| [hide]Climate data for Perth, Western Australia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 45.8 (114.4) |

46.2 (115.2) |

42.4 (108.3) |

37.6 (99.7) |

34.3 (93.7) |

28.1 (82.6) |

26.3 (79.3) |

27.8 (82) |

34.2 (93.6) |

37.3 (99.1) |

40.3 (104.5) |

44.2 (111.6) |

46.2 (115.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 31.3 (88.3) |

31.7 (89.1) |

29.6 (85.3) |

25.9 (78.6) |

22.3 (72.1) |

19.4 (66.9) |

18.4 (65.1) |

19.1 (66.4) |

20.4 (68.7) |

23.4 (74.1) |

26.6 (79.9) |

29.1 (84.4) |

24.8 (76.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 24.8 (76.6) |

25.1 (77.2) |

23.1 (73.6) |

19.9 (67.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

14.0 (57.2) |

13.1 (55.6) |

13.7 (56.7) |

15.0 (59) |

17.5 (63.5) |

20.5 (68.9) |

22.8 (73) |

18.8 (65.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 18.2 (64.8) |

18.4 (65.1) |

16.6 (61.9) |

13.8 (56.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

8.6 (47.5) |

7.7 (45.9) |

8.3 (46.9) |

9.6 (49.3) |

11.5 (52.7) |

14.3 (57.7) |

16.4 (61.5) |

12.8 (55) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 8.9 (48) |

8.7 (47.7) |

6.3 (43.3) |

4.1 (39.4) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

0.0 (32) |

1.3 (34.3) |

1.0 (33.8) |

2.2 (36) |

5.0 (41) |

7.9 (46.2) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 15.4 (0.606) |

8.8 (0.346) |

20.5 (0.807) |

36.5 (1.437) |

90.2 (3.551) |

126.7 (4.988) |

144.7 (5.697) |

122.4 (4.819) |

88.0 (3.465) |

38.6 (1.52) |

23.7 (0.933) |

9.9 (0.39) |

730.5 (28.76) |

| Average precipitation days | 2.4 | 2.1 | 4.1 | 6.7 | 11.1 | 15.2 | 16.9 | 15.7 | 15.3 | 8.7 | 6.3 | 3.9 | 108.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 39 | 38 | 39 | 46 | 50 | 56 | 57 | 54 | 53 | 46 | 44 | 41 | 47 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 360.6 | 314.9 | 295.5 | 246.0 | 211.7 | 180.6 | 188.4 | 219.8 | 232.4 | 299.8 | 320.4 | 359.4 | 3,229.5 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 11.5 | 11.0 | 9.6 | 8.3 | 6.9 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 7.2 | 7.7 | 9.6 | 10.6 | 11.5 | 8.8 |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology[54][55][56] Temperatures: 1993–2015; Extremes: 1897–2015; Rain data: 1876–2012 |

|||||||||||||

| [show]Climate data for Fremantle |

|---|

| [show]Climate data for Kalamunda |

|---|

| [show]Climate data for Jandakot Airport |

|---|

Isolation

Perth is one of the most isolated major cities in the world. The nearest city with a population of more than 100,000 is Adelaide, 2,104 kilometres (1,307 mi) away. Only Honolulu (population 953,000), 3,841 kilometres (2,387 mi) from San Francisco, is more isolated.Perth is geographically closer to both Dili, East Timor (2,785 kilometres (1,731 mi)), and Jakarta, Indonesia (3,002 kilometres (1,865 mi)), than to Sydney (3,291 kilometres (2,045 mi)), Brisbane (3,604 kilometres (2,239 mi)), or Canberra (3,106 kilometres (1,930 mi)).

Demographics

| [show]Historical populations |

|---|

Ethnic groups

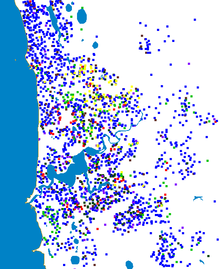

One dot represents 100 persons born in:

United Kingdom (dark blue),

China (red),

Italy (light green),

Malaysia (dark green),

South Africa (brown),

Singapore (purple) and

Vietnam (yellow), based on 2006 Census.

United Kingdom (dark blue),

China (red),

Italy (light green),

Malaysia (dark green),

South Africa (brown),

Singapore (purple) and

Vietnam (yellow), based on 2006 Census.

Perth's population is notable for the high proportion of British and Irish born residents. At the 2006 Census, 142,424 England-born Perth residents were counted,[64] narrowly behind Sydney (145,261),[65] despite the fact that Perth had just 35% of the overall population of Sydney.

The ethnic make-up of Perth changed in the second part of the 20th century, when significant numbers of continental European immigrants arrived in the city. Prior to this, Perth's population had been almost completely Anglo-Celtic in ethnic origin. As Fremantle was the first landfall in Australia for many migrant ships coming from Europe in the 1950s and 1960s, Perth started to experience a diverse influx of people, including Italians, Greeks, Dutch, Germans, Croats. The Italian influence in the Perth and Fremantle area has been substantial, evident in places like the "Cappuccino strip" in Fremantle featuring many Italian eateries and shops. In Fremantle the traditional Italian blessing of the fleet festival is held every year at the start of the fishing season. In Northbridge every December is the San Nicola (Saint Nicholas) Festival, which involves a pageant followed by a concert, predominantly in Italian. Suburbs surrounding the Fremantle area, such as Spearwood and Hamilton Hill, also contain high concentrations of Italians, Croatians and Portuguese. Perth also has a small Jewish community – numbering 5,082 in 2006[62] – who have emigrated primarily from Eastern Europe and more recently from South Africa.

Another more recent wave of arrivals includes white minorities from Southern Africa. South African residents overtook those born in Italy as the fourth largest foreign group in 2001. By 2006, there were 18,825 South Africans residing in Perth, accounting for 1.3% of the city's population.[64] Many Afrikaners and Anglo-Africans emigrated to Perth during the 1980s and 1990s, with the phrase "packing for Perth" becoming associated with South Africans who choose to emigrate abroad, sometimes regardless of the destination.[66] As a result, the city has been described as "the Australian capital of South Africans in exile".[67] The reason for Perth being so popular among white South Africans has often been the location, the vast amount of land, and the slightly warmer climate compared to other large Australian cities – Perth has a Mediterranean climate reminiscent of Cape Town.

Since the late 1970s, Southeast Asia has become an increasingly important source of migrants, with communities from Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore, Hong Kong, Mainland China, and India all now well-established. There were 53,390 persons of Chinese descent in Perth in 2006 – 2.9% of the city's population.[68] These are supported by the Australian Eurasian Association of Western Australia,[69] which also serves a community of Portuguese-Malacca Eurasian or Kristang immigrants.[70]

The Indian community includes a substantial number of Parsees who emigrated from Bombay – Perth being the closest Australian city to India – and the India-born population of the city at the time of the 2006 census was 14,094 or 0.8%.[68] Perth is also home to the largest population of Anglo-Burmese in the world; many settled here following the independence of Burma in 1948 and the city is now the cultural hub for Anglo-Burmese worldwide.[citation needed] There is also a substantial Anglo-Indian population in Perth, who also settled in the city following the independence of India.

Religion

Protestants, predominantly Anglican, make up approximately 28% of the population.[71][72] Perth is the seat of the Anglican Diocese of Perth[73] and of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Perth.[74] Roman Catholics make up about 23% of the population,[71] and Catholicism is the most common single denomination.[71] Perth is also home to 12,000 Latter-day Saints[75] and the Perth Australia Temple of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Perth is also home of the seat of the Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of the Southern Cross as the Church of St Ninian and St Chad in Perth was named the principal church of the ordinariate.[76]Buddhism and Islam each claim more than 20,000 adherents.[71] Perth has the third largest Jewish populations in Australia,[77] numbering approximately 20,000,[71] with both Orthodox and Progressive synagogues and a Jewish Day School.[78] The Bahá'í community in Perth numbers around 1,500.[71] Hinduism has over 20,000 adherents in Perth;[71] the Diwali (festival of lights) celebration in 2009 attracted over 20,000 visitors. There are Hindu temples in Canning Vale, Anketell and a Swaminarayan temple north of the Swan River.[79] Hinduism is the fastest growing religion in Australia.[80]

Approximately one in five people from Perth profess to having no religion, with 11% of people not specific as to their beliefs.[81] One hundred years ago this figure was one in 250 (0.4%).[81] Internationally this is not an isolated occurrence as other countries such as New Zealand and Great Britain are reporting similar increases.[81]

Governance

Supreme Court of Western Australia

Government House, Western Australia

Parliament House, Perth

The state's highest court, the Supreme Court, is located in Perth,[82] along with the District[83] and Family[84] Courts. The Magistrates' Court has six metropolitan locations.[85] The Federal Court of Australia and the Federal Circuit Court of Australia (previously the Federal Magistrates Court)[86][87] occupy the Commonwealth Law Courts building on Victoria Avenue,[88] which is also the location for annual Perth sittings of Australia's High Court.[89]

The administrative region of Perth includes 30 local governments, with the outer extent being the City of Wanneroo and the City of Swan to the north, the Shire of Mundaring, Shire of Kalamunda and the City of Armadale to the east, the Shire of Serpentine-Jarrahdale to the southeast and the City of Rockingham to the southwest, and including the islands of Rottnest Island and Garden Island off the west coast;[90] this also correlates with the Metropolitan Region Scheme. Perth can also be defined by its wider extent of Greater Perth.[91][92]

Economy

See also: Economy of Western Australia

By virtue of its population and role as the administrative centre for

business and government, Perth dominates the Western Australian

economy, despite the major mining, petroleum, and agricultural export

industries located elsewhere in the state.[93]

Perth's function as the state's capital city, its economic base and

population size have also created development opportunities for many

other businesses oriented to local or more diversified markets.Perth's economy has been changing in favour of the service industries since the 1950s. Although one of the major sets of services it provides is related to the resources industry and, to a lesser extent, agriculture, most people in Perth are not connected to either; they have jobs that provide services to other people in Perth.[94]

As a result of Perth's relative geographical isolation, it has never had the necessary conditions to develop significant manufacturing industries other than those serving the immediate needs of its residents, mining, agriculture and some specialised areas, such as, in recent times, niche ship building and maintenance. It was simply cheaper to import all the needed manufactured goods from either the eastern states or overseas.

Industrial employment influenced the economic geography of Perth. After WWII, Perth experienced suburban expansion aided by high levels of car ownership. Workforce decentralisation and transport improvements made it possible for the establishment of small-scale manufacturing in the suburbs. Many firms took advantage of relatively cheap land to build spacious, single-storey plants in suburban locations with plentiful parking, easy access and minimal traffic congestion. "The former close ties of manufacturing with near-central and/or rail-side locations were loosened."[93]

Industrial estates such as Kwinana, Welshpool and Kewdale were post-war additions contributing to the growth of manufacturing south of the river. The establishment of the Kwinana industrial area was supported by standardisation of the east-west rail gauge linking Perth with eastern Australia. Since the 1950s the area has been dominated by heavy industry, including an oil refinery, steel-rolling mill with a blast furnace, alumina refinery, power station and a nickel refinery. Another development, also linked with rail standardisation, was in 1968 when the Kewdale Freight Terminal was developed adjacent to the Welshpool industrial area, replacing the former Perth railway yards.[93]

With significant population growth post-WWII,[95] employment growth occurred not in manufacturing but in retail and wholesale trade, business services, health, education, community and personal services and in public administration. Increasingly it was these services sectors, concentrated around the Perth metropolitan area, that provided jobs.[93]

Education

See also: Education in Western Australia

Education is compulsory in Western Australia between the ages of six

and seventeen, corresponding to primary and secondary school.[96] Tertiary education is available through a number of universities and technical and further education (TAFE) colleges.Primary and secondary education

Students may attend either public schools, run by the state government's Department of Education, or private schools, usually associated with a religion.The Western Australian Certificate of Education (WACE) is the credential given to students who have completed Years 11 and 12 of their secondary schooling.[97]

In 2012 the minimum requirements for students to receive their WACE changed[how?].[98]

Tertiary education

The University of Western Australia, located in Crawley

The University of Western Australia, which was founded in 1911,[99] is renowned as one of Australia's leading research institutions.[100] The university's monumental neo-classical architecture, most of which is carved from white limestone, is a notable tourist destination in the city. It is the only university in the state to be a member of the Group of Eight, as well as the Sandstone universities. It is also the state's only university to have produced a Nobel Laureate[101] – Barry Marshall who graduated with a Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery in 1975 and was awarded a joint Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine in 2005, together with Robin Warren.

Curtin University (previously known as Western Australian Institute of Technology (1966-1986) and Curtin University of Technology (1986-2010) is Western Australia's largest university by student population.

Murdoch University was founded in the 1973, and incorporates Western Australia's only veterinary school.

Edith Cowan University was established in the early 1990s from the existing Western Australian College of Advanced Education (WACAE) which itself was formed in the 1970s from the existing Teachers Colleges at Claremont, Churchlands, and Mount Lawley. It incorporates the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts (WAAPA).

The University of Notre Dame Australia was established in 1990. Notre Dame was established as a Catholic university with its lead campus in Fremantle and a large campus in Sydney. Its campus is set in the west end of Fremantle, using historic port buildings built in the 1890s, giving Notre Dame a distinct European university atmosphere. Though Notre Dame shares its name with the University of Notre Dame in Indiana USA, it is a separate institution, claiming only "strong ties" with its American namesake.[citation needed]

Colleges of TAFE provide trade and vocational training, including certificate- and diploma-level courses. TAFE began as a system of technical colleges and schools under the Education Department, from which they were separated in the 1980s and ultimately formed into regional colleges. Four exist in the Perth metropolitan area: Central Institute of Technology (formerly Central TAFE); West Coast Institute of Training (northern suburbs); Polytechnic West (eastern and south-eastern suburbs; formerly Swan TAFE); and Challenger Institute of Technology (Fremantle/Peel).

Media

ABC Perth studios in East Perth, home of 720 ABC Perth radio and ABC television in Western Australia

- ABC

- ABC2/KIDS

- ABC3

- ABC News 24

- SBS

- SBS HD (SBS broadcast in HD)

- SBS2

- Food Network

- NITV

- Seven

- 7HD (Seven broadcast in HD)

- 7Two

- 7mate

- 7flix

- TV4ME

- Racing.com

- Nine

- 9HD (Nine broadcast in HD)

- 9Gem

- 9Go!

- 9Life

- eXtra

- Ten

- Ten HD (Ten broadcast in HD)

- One

- Eleven

- TVSN

- Spree TV

- West TV (Perth's community TV station)

Foxtel provides a subscription-based satellite and cable television service. Perth has its own local newsreaders on ABC (James McHale), Seven (Rick Ardon, Susannah Carr), Nine (Emmy Kubainski, Tim McMillan) and Ten (Narelda Jacobs).

Television shows produced in Perth include local editions of the current affair program Today Tonight, and other types of programming such as The Force. An annual telethon has been broadcast since 1968 to raise funds for charities including Princess Margaret Hospital for Children. The 24-hour Perth Telethon claims to be "the most successful fundraising event per capita in the world"[103] and raised more than A$20 million in 2013, with a combined total of over A$153 million since 1968.[104]

The main newspapers for Perth are The West Australian and The Sunday Times. Localised free community papers cater for each local government area. There are also many advertising newspapers, such as The Quokka. The local business paper is Western Australian Business News.

Radio stations are on AM, FM and DAB+ frequencies. ABC stations include News Radio (585AM), 720 ABC Perth, Radio National (810AM), Classic FM (97.7FM) and Triple J (99.3FM). The six local commercial stations are: 92.9, Nova 93.7, Mix 94.5, 96fm, on FM and 882 6PR and 1080 6IX on AM. DAB+ has mostly the same as both FM and AM plus national stations from the ABC/SBS, Radar Radio and Novanation, along with local stations My Perth Digital and HotCountry Perth. Major community radio stations include RTRFM (92.1FM), Sonshine FM (98.5FM),[105] SportFM (91.3FM)[106] and Curtin FM (100.1FM).[107]

Online news media covering the Perth area include TheWest.com.au backed by The West Australian, Perth Now from the newsroom of The Sunday Times, WAToday from Fairfax Media and other outlets like TweetPerth[108] on social media.

Culture

Arts and entertainment

See also: Music of Perth; List of musical acts from Western Australia; and People from Perth, Western Australia

Public art by artist Akio Makigawa outside the State Library of Western Australia

Perth is also home to the internationally regarded Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts at Edith Cowan University, from which many successful actors and broadcasters have launched their careers.[116][117] The city's main performance venues include the Riverside Theatre within the Perth Convention Exhibition Centre,[118] the Perth Concert Hall,[119] the historic His Majesty's Theatre,[120] the Regal Theatre in Subiaco[121] and the Astor Theatre in Mount Lawley.[122] Perth Arena can be configured as an entertainment or sporting arena, and concerts are also hosted at other sporting venues, including Subiaco Oval, HBF Stadium, and nib Stadium. Outdoor concert venues include Quarry Amphitheatre, Supreme Court Gardens, Kings Park and Russell Square.

Soundwave Perth in 2010

Annual events

A number of annual events are held in Perth. The Perth International Arts Festival is a large cultural festival that has been held annually since 1953, and has since been joined by the Winter Arts festival, Perth Fringe Festival, and Perth Writers Festival. Perth also hosts annual music festivals including Future Music, Stereosonic and Soundwave. The Perth International Comedy Festival features a variety of local and international comedic talent, with performances held at the Astor Theatre and nearby venues in Mount Lawley, and regular night food markets throughout the summer months across Perth and its surrounding suburbs. Sculpture by the Sea showcases a range of local and international sculptors' creations along Cottesloe Beach. There is also a wide variety of public art and sculptures on display across the city, throughout the year.

The Noodle Night Markets in March at the Perth Cultural Centre

Artistic mediums

Perth has featured in a variety of artistic works in various mediums. An early novel, Moondyne, set in the Swan River Colony, was written by a former Fenian convict, John Boyle O'Reilly, and a A Faithful Picture, edited by Peter Cowan, gives a good idea of the early days of the colony. Songs that refer to the city include "I Love Perth" (1996) by Pavement, and "Perth" (2011) by Bon Iver, while a number of films feature Perth: Last Train to Freo, Two Fists, One Heart, Thunderstruck, Bran Nue Dae, Japanese Story and Nickel Queen. The industrial metal band Fear Factory recorded the video for their single "Cyberwaste" in South Fremantle.Famous people

Because of Perth's relative isolation from other Australian cities, overseas artists often exclude it from their Australian tour schedules. This isolation, however, has developed a strong local music scene, and the development of local music groups such as John Butler Trio, The Triffids, Pendulum, Eskimo Joe, Pond, Tame Impala, Karnivool, Gyroscope, Jebediah, Little Birdy, The Panics and Birds of Tokyo. Celebrity musical performers from Perth have included the late AC/DC lead singer Bon Scott, who has been remembered with a statue in Fremantle, and veteran performer and artist Rolf Harris, given the nickname "The Boy From Bassendean". The largest performance area within the State Theatre Centre, the Heath Ledger Theatre, is named in honour of Perth-born film actor Heath Ledger.Tourism and recreation

Main article: Tourism in Perth

Fremantle is known for its well-preserved architectural heritage.

The Murray Street mall, at the corner of Forrest Place

Kings Park, located in central Perth between the CBD and the University of Western Australia, is one of the world's largest inner-city parks,[128] at 400.6 hectares (990 acres).[129] There are many landmarks and attractions within Kings Park, including the State War Memorial Precinct on Mount Eliza, Western Australian Botanic Garden, and children's playgrounds. Other features include DNA Tower, a 15m high double helix staircase that resembles the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) molecule,[130] and Jacob's Ladder, comprising 242 steps that lead down to Mounts Bay Road. Hyde Park is another inner-city park located 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) north of the CBD. It was gazetted as a public park in 1897, created from 15 hectares (37 acres) of a chain of wetlands known as Third Swamp.[131] Avon Valley, John Forrest and Yanchep national parks are areas of protected bushland at the northern and eastern edges of the metropolitan area. Within the city's northern suburbs is Whiteman Park, a 4,000-hectare (9,900-acre) bushland area, with bushwalking trails, bike paths, sports facilities, playgrounds, a vintage tramway, a light railway on a 6-kilometre (3.7 mi) track, motor and tractor museums, and Caversham Wildlife Park.

Perth Zoo, located in South Perth, houses a variety of Australian and exotic animals from around the globe. The zoo is home to highly successful breeding programs for orangutans and giraffes, and participates in captive breeding and reintroduction efforts for a number of Western Australian species, including the numbat, the dibbler, the chuditch, and the western swamp tortoise.[132] More wildlife can be observed at the Aquarium of Western Australia in Hillarys, which is Australia's largest aquarium, specialising in marine animals that inhabit the 12,000-kilometre-long (7,500 mi) western coast of Australia. The northern Perth section of the coastline is known as Sunset Coast; it includes numerous beaches and the Marmion Marine Park, a protected area inhabited by tropical fish, Australian sea lions and bottlenose dolphins, and traversed by humpback whales. Tourist Drive 204, also known as Sunset Coast Tourist Drive, is a designated route from North Fremantle to Iluka along coastal roads.

Sport

Main article: Sport in Western Australia

Domain Stadium, the home stadium of Australian rules football and many other sports in Perth

Western Australian Basketball League

The Western Australian Basketball League is WA's elite junior basketball competition.[135] Twelve clubs from around Perth and the South West compete in a 16 week season in addition to 4 weeks of finals; beginning in April it finishes by the end of September.[135] The twelve clubs are split into two conferences: the north includes the East Perth Eagles, Kalamunda Eastern Suns, Perth Redbacks, Perry Lakes Hawks, Stirling Senators and Wanneroo Wolves; the south includes the Cockburn Cougars, Lakeside Lightning, Mandurah Magic, Rockingham Flames, Southwest Slammers and Wiletton Tigers.[135] The competition is open to the following age groups: U12, U14, U16, U18, U20 (men) and open (D-League).[135]Current sport teams

The exterior of Perth Arena

The WACA Ground opened in the 1890s and has hosted Test cricket since 1970. The Western Australian Athletics Stadium opened in 2009.

Infrastructure

Health

See also: List of hospitals in Western Australia

Royal Perth Hospital, on either side of Wellington Street in the centre of Perth

New hospitals are under construction to replace ageing facilities. A new children's hospital, due to open in 2015, is being constructed next to Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, and will replace Princess Margaret Hospital.[138] Midland Health Campus, a public and a private hospital, is under construction in Midland. St John of God Health Care will build and operate the new hospitals under a public-private partnership with the state government. Midland Health Campus will open in late 2015, and replace the nearby Swan District Hospital.[139]

A number of other public and private hospitals operate in Perth.[140]

Transport

Main article: Transport in Perth, Western Australia

Further information: Transperth

The Kwinana Freeway links Perth and its surrounding suburbs to the city of Mandurah

Perth has a road network with three freeways and nine metropolitan highways. The Northbridge tunnel, part of the Graham Farmer Freeway, is the only significant road tunnel in Perth.

Perth metropolitan public transport, including trains, buses and ferries, are provided by Transperth, with links to rural areas provided by Transwa. There are 70 railway stations and 15 bus stations in the metropolitan area.

Perth Underground Train Station

The Indian Pacific passenger rail service connects Perth with Adelaide and Sydney once per week in each direction. The Prospector passenger rail service connects Perth with Kalgoorlie via several Wheatbelt towns, while the Australind connects to Bunbury, and the AvonLink connects to Northam.

Rail freight terminates at the Kewdale Rail Terminal, 15 km (9 mi) south-east of the city centre.

Perth's main container and passenger port is at Fremantle, 19 km (12 mi) south west at the mouth of the Swan River.[141] A second port complex is planned to be developed in Cockburn Sound primarily for the export of bulk commodities.

Utilities

Perth's electricity is generated, supplied, and retailed by three Western Australian Government corporations. Verve Energy operates coal and gas power generation stations, as well as wind farms and other power sources.[142] The physical network is maintained by Western Power,[143] while Synergy, the state's largest energy retailer, sells electricity to residential and business customers.[144]Alinta Energy, which was previously a government owned company, had a monopoly in the domestic gas market since the 1990s. However, in 2013 Kleenheat Gas began operating in the market, allowing consumers to choose their gas retailer.[145]

The Water Corporation is the dominant supplier of water, as well as wastewater and drainage services, in Perth and throughout the Western Australia. It is also owned by the state government.[146]

Water supply

Reduced rainfall in the region in recent years has lowered inflow to reservoirs by two-thirds over the last 30 years, and affected groundwater levels. Coupled with the city's relatively high growth rate, this had led to concerns that Perth could run out of water in the near future.[147] The Western Australian State Government responded by introducing mandatory household sprinkler restrictions in the city. The Kwinana Desalination Plant was opened in November 2006, able to supply over 45 gigalitres (10 billion imperial or 12 billion US gallons) of potable water per year;[148][149] its power requirements were met by the construction of the Emu Downs Wind Farm near Cervantes.[150] Consideration was given to piping water from the Kimberley region, but the idea was rejected in May 2006 due primarily to its high cost.[151] Other proposals under consideration included the controversial extraction of an extra 45 gigalitres of water a year from the Yarragadee Aquifer in the south-west of the state. However, in May 2007, the state government announced that a second desalination plant will be built at Binningup, on the coast between Mandurah and Bunbury.[152] A trial winter (1 June – 31 August) sprinkler ban was introduced in 2009 by the State Government, a move which the Government later announced would be made permanent.[153] In September 2009 Western Australia's dams reached 50% overall capacity for the first time since 2000.[154]See also

References

- "Dams at record levels". ABC News. 15 September 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Perth. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Perth (Australia). |

- Watch historical footage of Perth and Western Australia from the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia's collection.

- Historical photos of Perth from the State Library of Western Australia

- Tourism Australia Page

|

||

|

||

|

|||

|

||

|

• In 2006 the estimated resident Aboriginal population of Western Australia was 77,900 persons, an increase of 18% from the 2001 Census • In 2006 34% of Aboriginal people in Western Australia lived in and around the Perth metropolitan arealine feed character in

|quote= at position 87 (help)The University of Western Australia has helped to shape the careers of more than 75,000 graduates since it was established in 1911.

A document dated 12 January obtained by The West Australian under Freedom of Information laws shows that the Water Corporation fears Perth will begin running out of water by late 2008 without one of the two developments.

When fully operational it will produce on average 130 million litres per day and supply 17 per cent of Perth's needs.

Ghost town

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For settlements that never existed, see Phantom settlement. For other uses, see Ghost town (disambiguation).

Plymouth, Montserrat, is the only ghost town which is the capital of a political territory.

Some ghost towns, especially those that preserve period-specific architecture, have become tourist attractions. Some examples are Bannack, Montana; Calico, California; Centralia, Pennsylvania; Oatman, Arizona; and South Pass City, Wyoming in the United States; Barkerville, British Columbia in Canada; Craco in Italy; Elizabeth Bay and Kolmanskop in Namibia; Pripyat in Ukraine; and Danushkodi in India. Visiting, writing about, and photographing ghost towns is a minor industry.

The town of Plymouth on the Caribbean island of Montserrat is a ghost town which is the de jure capital of Montserrat.

Contents

Definition

The definition of a ghost town varies between individuals, and between cultures. Some writers discount settlements that were abandoned as a result of a natural or human-made disaster or other causes using the term only to describe settlements which were deserted because they were no longer economically viable; T. Lindsey Baker, author of Ghost Towns of Texas, defines a ghost town as "a town for which the reason for being no longer exists".[1] Some believe that any settlement with visible tangible remains should not be called a ghost town;[2] others say, conversely, that a ghost town should contain the tangible remains of buildings.[3] Whether or not the settlement must be completely deserted, or may contain a small population, is also a matter for debate.[2] Generally, though, the term is used in a looser sense, encompassing any and all of these definitions. The American author Lambert Florin's preferred definition of a ghost town was simply "a shadowy semblance of a former self".[4]Reasons for abandonment

Factors leading to abandonment of towns include depleted natural resources, economic activity shifting elsewhere, railroads and roads bypassing or no longer accessing the town, human intervention, disasters, massacres, wars, and the shifting of politics or fall of empires.[5] A town can also be abandoned when it is part of an exclusion zone due to natural or man-made causes.Economic activity shifting elsewhere

As farms industrialize, smaller farms are no longer economically viable, leading to rural decay.

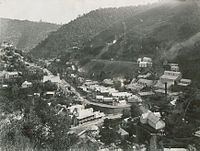

The dismantling of a boomtown can often occur on a planned basis. Mining companies nowadays will create a temporary community to service a mine site, building all the accommodation shops and services required, and then removing them once the resource has been extracted. Modular buildings can be used to facilitate the process. A gold rush would often bring intensive but short-lived economic activity to a remote village, only to leave a ghost town once the resource was depleted.

In some cases, multiple factors may remove the economic basis for a community; some former mining towns on U.S. Route 66 suffered both mine closures when the resources were depleted and loss of highway traffic as US 66 was diverted away from places like Oatman, Arizona onto a more direct path.

The Middle East has many ghost towns that were created when the shifting of politics or the fall of empires caused capital cities to be socially or economically unviable, such as Ctesiphon.

The rise of condo investment caused for real estate bubbles also leads to a ghost town, as real estate prices rise and affordable housing become less available. Such examples include China and Canada, where housing is often used as an investment rather than for habitation.

Human intervention

Prior to the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974, Varosha, now falling into ruin, once was a modern tourist area.

River re-routing is another factor, one example being the towns along the Aral Sea.

Ghost towns may be created when land is expropriated by a government and residents are required to relocate. One example is the village of Tyneham in Dorset, England, acquired during World War II to build an artillery range.

A similar situation occurred in the U.S. when NASA acquired land to construct the John C. Stennis Space Center (SSC), a rocket testing facility in Hancock County, Mississippi (on the Mississippi side of the Pearl River, which is the Mississippi–Louisiana state line). This required NASA to acquire a large (approximately 34-square-mile (88 km2)) buffer zone because of the loud noise and potential dangers associated with testing such rockets. Five thinly populated rural Mississippi communities (Gainesville, Logtown, Napoleon, Santa Rosa, and Westonia), plus the northern portion of a sixth (Pearlington), along with 700 families in residence, had to be completely relocated off the facility.

Sometimes the town might cease to officially exist, but the physical infrastructure remains. For example, the five Mississippi communities that had to be abandoned to build SSC still have remnants of those communities within the facility itself. These include city streets, now overgrown with forest flora and fauna, and a one-room school house. Another example of infrastructure remaining is the former town of Weston, Illinois, which voted itself out of existence and turned the land over for construction of the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. Many houses and even a few barns remain, used for housing visiting scientists and storing maintenance equipment, while roads that used to cross through the site have been blocked off at the edges of the property, with gatehouses or simply barricades to prevent unsupervised access.

Flooding by dams

Construction of dams has produced ghost towns that have been left underwater. Examples include the settlement of Loyston, Tennessee, U.S., inundated by the creation of Norris Dam. The town was reorganised and reconstructed on nearby higher ground. Other examples are The Lost Villages of Ontario flooded by Saint Lawrence Seaway construction in 1958, the hamlets of Nether Hambleton and Middle Hambleton in Rutland, England, which were flooded to create Rutland Water, and the villages of Ashopton and Derwent, England, flooded during the construction of the Ladybower Reservoir. Mologa in Russia was flooded by the creation of Rybinsk reservoir, and in France the Tignes Dam flooded the village of Tignes, displacing 78 families. Many ancient villages had to be abandoned during construction of the Three Gorges Dam in China, leading to displacement of many rural people. In the Costa Rican province of Guanacaste, the town of Arenal was rebuilt to make room for the man-made Lake Arenal. The old town now lies submerged below the lake. Old Adaminaby was flooded by a dam of the Snowy River Scheme. Construction of the Aswan High Dam on the Nile River in Egypt submerged archaeological sites and ancient settlements such as Buhen under Lake Nasser.Massacres

Some towns become deserted when their populations are massacred. The original French village at Oradour-sur-Glane was destroyed on 10 June 1944 when 642 of its 663 inhabitants, including women and children, were killed by a German Waffen-SS company. A new village was built after the war on a nearby site, and the ruins of the original have been maintained as a memorial.Disasters, actual and anticipated

Craco, Italy, was abandoned due to a landslide in 1963. Now it is a popular film set.

Craco, a medieval village in the Italian region of Basilicata, was evacuated after a landslide in 1963. Nowadays it is a famous filming location for many movies, including The Passion of The Christ by Mel Gibson, Christ Stopped at Eboli by Francesco Rosi, The Nativity Story by Catherine Hardwicke and Quantum of Solace by Marc Forster.[6]

In 1984, Centralia, Pennsylvania was abandoned due to an uncontainable mine fire, which began in 1962 and still rages to this day; eventually the fire reached an abandoned mine underneath the nearby town of Byrnesville, Pennsylvania, which caused that mine to catch on fire too and forced the evacuation of that town as well.

Pripyat, Ukraine, was abandoned after the Chernobyl disaster.

Following the Chernobyl disaster of 1986, dangerously high levels of nuclear radiation escaped into the surrounding area, and nearly 200 towns and villages in Ukraine and neighbouring Belarus were evacuated, including the city of Pripyat. The area was, and still is, so contaminated with nuclear radiation that many of the evacuees were never permitted to return to their homes. Pripyat is the most famous of these abandoned towns; it was built for the workers of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant and had a population of almost 50,000 at the time of the disaster.[7] A similarly large-scale evacuation followed the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan, and some towns within the exclusion zone, such as Tomioka, remain abandoned.

Disease and contamination

Ghost town Rerik-West in Mecklenburg, Germany. Abandoned by the Red Army after 1992, and turned into a restricted area due to ammunition contamination.

Catastrophic environmental damage caused by long-term contamination can also create a ghost town. Some notable examples are Times Beach, Missouri, whose residents were exposed to a high level of dioxins, and Wittenoom, Western Australia, which was once Australia's largest source of blue asbestos, but was shut down in 1966 due to health concerns. Treece and Picher, twin communities straddling the Kansas–Oklahoma border, were once one of the United States' largest sources of zinc and lead, but over a century of unregulated disposal of mine tailings led to groundwater contamination and lead poisoning in the town's children, eventually resulting in a mandatory Environmental Protection Agency buyout and evacuation. Contamination due to ammunition caused by military use may also lead to the development of ghost towns.

Revived ghost towns

Walhalla, Victoria was almost abandoned after being mined for gold, but is now becoming repopulated.

| This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Alexandria, the second largest city of Egypt, was a flourishing city in the Ancient era, but declined during the Middle Ages. It underwent a dramatic revival during the 19th century; from a population of 5,000 in 1806, it grew into a city of over 200,000 inhabitants by 1882,[11] and is now home to over four million people.[12]

In Algeria, many cities became hamlets after the end of Late Antiquity. They were revived with shifts in population during and after French colonization of Algeria. Oran, currently the nation's second largest city with 1 million people, was a village of only a few thousand people before colonization.

Foncebadón, a village in León, Spain that was mostly abandoned and only inhabited by a mother and son, is slowly being revived owing to the ever-increasing stream of pilgrims on the road to Santiago de Compostela.

Around the world

See also: List of ghost towns by country

Africa

Kolmanskop, Namibia

Many of the ghost towns in mineral-rich Africa are former mining towns. Shortly after the start of the 1908 diamond rush in German South-West Africa, now known as Namibia, the German Imperial government claimed sole mining rights by creating the Sperrgebiet (forbidden zone),[16] effectively criminalizing new settlement. The small mining towns of this area, among them Pomona, Elizabeth Bay and Kolmanskop, were exempt from this ban, but the denial of new land claims soon rendered all of them ghost towns.

Asia

Remnants of the Dhanushkodi Railway Station in India

The town of Dhanushkodi, India is a ghost town.

Many abandoned towns and settlements in the former Soviet Union were established near Gulag concentration camps to supply necessary services. Since most of these camps were abandoned in the 1950s, the towns were abandoned as well. One such town is located near the former Gulag camp called Butugychag (also called Lower Butugychag). Other towns were deserted due to deindustrialisation and the economic crises of the early 1990s attributed to post-Soviet conflicts.

A recent example of a ghost town is Ōkuma, Fukushima in Japan after the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami.

Antarctica

The derelict British base in Whalers Bay, Deception Island, destroyed by a volcanic eruption

The Antarctic island of South Georgia used to have several thriving whaling settlements during the first half of the 20th century, with a combined population exceeding 2,000 in some years. These included Grytviken (operating 1904-64), Leith Harbour (1909–65), Ocean Harbour (1909–20), Husvik (1910–60), Stromness (1912–61) and Prince Olav Harbour (1917–34). The abandoned settlements have become increasingly dilapidated, and remain uninhabited nowadays except for the Museum curator's family at Grytviken. The jetty, the church, and dwelling and industrial buildings at Grytviken have recently been renovated by the South Georgian Government, becoming a popular tourist destination. Some historical buildings in the other settlements are being restored as well.

Europe

Main street of Oradour-sur-Glane, France, unchanged since the German massacre.

In Spain, large zones of the mountainous Iberian System and the Pyrenees have undergone heavy depopulation since the early 20th century, leaving a string of ghost towns in areas such as the Solana Valley. Traditional agricultural practices such as sheep and goat rearing, on which the mountain village economy was based, were not taken over by the local youth, especially after the lifestyle changes that swept over rural Spain during the second half of the 20th century.[20]

In the United Kingdom, thousands of villages were abandoned during the Middle Ages, as a result of Black Death, climate change, revolts, and enclosure, the process by which vast amounts of farmland became privately owned. Since there are rarely any visible remains of these settlements, they are not generally considered ghost towns; instead, they are referred to in archaeological circles as deserted medieval villages.

Sometimes, wars and genocide end a town's life. In 1944, occupying German Waffen-SS troops murdered the population of the French village Oradour-sur-Glane. A new settlement was built nearby after the war, but the old town was left depopulated on the orders of President Charles de Gaulle, as a permanent memorial. In Germany, numerous smaller towns and villages in the former eastern territories were completely destroyed in the last two years of the war. These territories later became part of Poland and the Soviet Union, and many of the smaller settlements were never rebuilt or repopulated, for example Kłomino (Westfalenhof), Pstrąże (Pstransse), and Janowa Góra (Johannesberg). Some villages in England were also abandoned during the war, but for different reasons. Imber and Tyneham, along with several villages in the Stanford Battle Area, were commandeered by the War Office for use as training grounds for British and US troops. Although this was intended to be a temporary measure, the residents were never allowed to return, and the villages have been used for military training ever since.

Disasters have played a part in the abandonment of settlements within Europe. After the Chernobyl disaster of 1986, the city of Pripyat in Ukraine was evacuated due to dangerous radiation levels within the area. As of today, Pripyat remains completely abandoned, and has no remaining inhabitants.

North America

Robsart Hospital, one of many abandoned buildings in Robsart, Saskatchewan

Canada

See also: Lists of ghost towns in Canada

There are ghost towns in parts of British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, Saskatchewan, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Quebec. Some were logging towns or dual mining and logging sites, often developed at the behest of the company.

In Alberta and Saskatchewan, most ghost towns were once farming

communities that have since died off due to the removal of the railway

through the town or the bypass of a highway. The ghost towns in British

Columbia were predominantly mining towns and prospecting camps as well

as canneries and, in one or two cases, large smelter and pulp mill

towns. British Columbia has more ghost towns than any other jurisdiction

on the North American continent, with one estimate at the number of

abandoned and semi-abandoned towns and localities upwards of 1500.[21] Among the most notable are Anyox, Kitsault, and Ocean Falls.Some ghost towns have revived their economies and populations due to historical and eco-tourism, such as Barkerville. Barkerville, once the largest town north of Kamloops, is now a year-round Provincial Museum. In Québec, Val-Jalbert is a well-known tourist ghost town; founded in 1901 around a mechanical pulp mill which became obsolete when paper mills began to break down wood fibre by chemical means, it was abandoned when the mill closed in 1927 and re-opened as a park in 1960.

United States

Bannack, Montana, a well-preserved ghost town that is now a state park.

See also: List of ghost towns in the United States

There are many ghost towns or abandoned communities in the American Great Plains,

the rural areas of which have lost a third of their population since

1920. Thousands of communities in the northern plains states of Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota and South Dakota became railroad ghost towns when a rail line failed to materialize. Hundreds more towns were abandoned when the US Highway System replaced the railroads as the favored mode of travel. Ghost towns are common in mining or mill towns

in all the western states, and many eastern and southern states as

well. Residents are compelled to leave in search of more productive

areas when the resources that had created an employment boom in these

towns were eventually consumed. Some unincorporated towns become ghost

towns due to flooding caused by dam projects that created man–made

lakes, such as Oketeyeconne.

Cook Bank building in Rhyolite, Nevada

1881 Assay building in what was once Vulture City, a mining town in Wickenburg, Arizona

Starting in 2002, an attempt to declare an "official ghost town" in California stalled when the adherents of the town of Bodie, in Northern California, and those of Calico, in Southern California, could not agree on the most deserving settlement for the recognition. A compromise was eventually reached – Bodie became the "official state gold rush ghost town", while Calico was named the "official state silver rush ghost town".[24]

On April 10, 2015, at the West Texas Historical Association's 92nd annual meeting, at Amarillo College in Amarillo, presented a program on ghost towns in Texas. Scheduled participants were James B. Hays of Brownwood, "Walthall and the Early Settlement of Southern Runnels County"; Mildred Sentell of Snyder, "Black Gold and the Ghost Town of Burnham, Garza County", and Christena Stephens of Nazareth, Texas, "How Mortality Records Can Provide a Historical Picture of a German Community."[25]

Latin America

| This section does not cite any sources. (September 2015) |

A number of ghost towns throughout Latin America were once mining camps or lumber mills, such as the many saltpeter mining camps that prospered in Chile from the end of the Saltpeter War until the invention of synthetic saltpeter during World War I. Some of these towns, such as the Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works in the Atacama Desert, have been declared UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Another former mining town, Real de Catorce in Mexico, has been used as a backdrop for Hollywood movies such as The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), The Mexican (2001), and Bandidas (2006).

See also

References

- "Ghost Towns and Cemeteries: The Eclipsing of Life for West Texans and Their Settlements" (PDF). West Texas Historical Association. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

Bibliography

- Baker, T. Lindsay (1991). Ghost Towns of Texas (2nd ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2189-0.

- McIntyre, Tobi; Politis, Paul (September–October 2005). "Standing legacy: Ghost towns preserve the Ottawa Valley's rich history". Canadian Geographic.

- Steinhilber, Berthold (2003). Ghost Towns of the American West. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0810945088.

- Wolle, Muriel Sibell (1977). Timberline Tailings: Tales of Colorado's Ghost Towns and Mining Camps (1st ed.). Athens, Ohio: Swallow Press/Ohio University Press. ISBN 0-8040-0963-5.

- Wolle, Muriel Sibell (1991). Stampede to Timberline: The Ghost Towns and Mining Camps of Colorado (2nd ed.). Athens, OH: Swallow Press/Ohio University Press. ISBN 0-8040-0946-5.

Further reading

- Curtis, Daniel R. "Pre-industrial societies and strategies for the exploitation of resources. A theoretical framework for understanding why some settlements are resilient and some settlements are vulnerable to crisis.". Academica.edu.

External links

|

|

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (November 2014) |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ghost towns. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Ghost towns. |

- Ghost Towns and History of the American and Canadian West

- Russian journalist explores the lives of illegal residents in the ghost town in the far-flung Russian Arctic

- Ten classic ghost towns worldwide

- Ghost Town Gallery (with about 200 ghost towns throughout the American west)

- Ghosts of North Dakota (an extensive collection of prairie ghost towns)

- Abandoned towns, villages and other communities in Great Britain

- Satellite images of ghost towns in China

- Ghost towns in Italy and worldwide (Italian)

- Ontario Abandoned Places (ghost towns in Canada)

- Ghost towns and historic locations in Colorado

- Ghost towns of Arizona and surrounding states

- New Day - Any Ghost Towns or abandoned structures from 1800s or earlier near where you live?, blog on DailyKos, 18 July 2013.

- Yahoo Travel article on ghost towns and other abandoned places

No comments:

Post a Comment