For most of the year, Iceberg Alley is gray and cold. The largest city on its shores, St. John’s, is known as “Canada’s Weather Champion.” Among major Canadian cities, the capital of Newfoundland and Labrador is the snowiest, windiest, wettest, and cloudiest, enjoying fewer than 1,500 hours of sunshine each year. Seattle, for comparison, gets 2,200 hours of sun annually. St. John’s is so overcast, the difference between it and Seattle is greater than that between Seattle and Tampa. But for a few months, from May to August, the sun breaks through the clouds and warms the freezing waves swirling off the coast.

In this brief window, when Newfoundland relishes nearly half of the sunshine it will absorb for the entire year, icebergs fill the Labrador Sea. The Arctic ice pack undergoes its seasonal melt and Baffin Bay thaws, allowing the frozen mountains to continue their journey toward the Atlantic. Most break off of glaciers on the west coast of Greenland—what glaciologists call “calving.” Speakers of a variety of languages, from Afrikaans to Uzbek, use the same word to define the process, as if the icy masses are the living offspring of glaciers. In Albanian, Farsi, and Italian, it is even more explicit: Glaciers “give birth.” Across cultures and languages, icebergs are conceptualized like wild cattle or horses roaming the maritime frontier in our rhetorical imagination. It is no wonder, then, that the International Ice Patrol and Canadian Ice Service describe the summertime influx of icebergs as an annual “migration.”

The final stage of an iceberg’s life is especially volatile and difficult to predict.

This is when iceberg cowboys head to sea. These rough-and-tumble mariners earn their living wrangling icebergs—sometimes to subdue and capture the leviathans, other times to herd the ice in new directions. They are undaunted by warnings issued by the International Ice Patrol. To that end, the brave seafarers make bad role models for academics interested in icebergs and ship captains navigating the North Atlantic. The iceberg cowboys, however, give us a hint of what it will take to harvest icebergs if we are ever going to use them to save the planet. They show us that these frozen beasts are not entirely unapproachable.

One million years ago, when mastodons roamed the Atlantic Coastal Plain in what is today New London, Connecticut, it was snowing in Greenland. We know this because glaciologists have taken ice cores from the center of the country. Using a drill that cuts a circle around a central point, they extract long, skinny tubes of ice. The process can take years, especially in a place like Greenland, where the ice sheet is more than 2 miles thick and drilling can only be done during the summer. Back in the lab, the glaciologists then analyze the ice to identify the particulates and chemicals captured by the falling snow. Using this information, they are able to reconstruct past climates and determine local temperature, greenhouse gas concentrations, and volcanic and solar activity.

The Greenland ice sheet was likely first formed some 3 million years ago, but it has grown and shrunk as the planet has warmed and cooled. It currently stretches 1,500 miles long by 680 miles wide and covers 80 percent of Greenland. Because most of the ice sheet is ringed by mountains, glaciers that lie along the coast like Sermeq Kujalleq function as outlets through which ice and water from the ice sheet come gushing out. Like rivers, glaciers are constantly flowing, pushed forward by the weight of their own ice. Sermeq Kujalleq, also known as Jakobshavn Glacier, travels an average of 130 feet in 24 hours and calves more than 11 cubic miles of icebergs each year into the Ilulissat Icefjord. Owing to this constant growth and shrinking, the oldest remaining known ice in the Greenlandic ice sheet today dates from the Pleistocene epoch, 1 million years ago.

Glaciers form when snow builds up and is buried each year by more and more snow. To understand the process, it helps to think of the snowball fights you might have had as a child. At normal atmospheric pressure, ice melts at 32 degrees Fahrenheit. Adding pressure, however, can lower the temperature at which this transformation, or solid-to-liquid phase change as we’re taught in chemistry class, occurs. Imagine squeezing a fistful of powdery snow. The force of your clasp manages to melt the snow just a bit. When you open your fingers and release the pressure, the snow refreezes into a harder, more solid lump. During a snowball fight, you might repeat this process a few times, adding a bit more fresh snow to the ball in your hand each time, until you create the perfect ammunition. In Greenland during the Pleistocene epoch, as more and more snow piled up, the ice crystals were compressed and recrystallized over centuries, forming rock-hard, crystal-clear glaciers.

To get to this ancient ice, we don’t always have to rely on glaciologists and their specialized drills. Instead, we can wait for icebergs to calve from glaciers and come to us; after all, they can travel thousands of miles before melting. For this reason, the famed Scottish geologist Charles Lyell believed icebergs transported boulders around the world. His dear friend Charles Darwin agreed, further suggesting that icebergs were responsible for the dispersion of species. While this theory has since been debunked, the 19th-century naturalists were correct that icebergs can act as transport vessels, bringing artifacts and stories from the past with them. In addition to chemicals and air bubbles trapped in snow, plants and animals can get caught on top of glaciers and become part of the historical record. Sometimes the findings are unbelievable. In the 19th century, several people reported seeing wooly mammoths frozen inside icebergs. Their shaggy hair and long, curled tusks were purportedly cryogenically preserved inside the ice. Another legend tells of a fully clad Viking encased in an iceberg, still gripping his spear and shield. Every time an iceberg floats by, an ancient piece of the past is carried along with it.

Glaciologists talk about “singing” icebergs, too.

Iceberg ice is not just primeval; it is also pristine. As snowflakes cascade through the atmosphere, they can catch sundry gaseous and particulate matter thanks to their latticework structures. Snow falling today, for instance, might absorb black carbon, mercury, formaldehyde, pesticides, and vehicle exhaust. Some scientists consequently advise children not to eat snow in urban areas. Thousands of years ago, however, the same pollutants were not floating around our atmosphere, so ancient glacial ice is comparatively immaculate. It has far fewer parts per million of impurities than most tap waters contain today. When glaciers calve, this unpolluted ice is packaged in a tidy parcel and launched into the salty sea.

Once an Arctic iceberg calves, it will typically live for three to six years, depending on its size and the journey it takes. An iceberg headed to the equator will melt faster than one grounded near the poles. Cycles of thawing and refreezing further create crevasses within the iceberg that can cause a berg to crumble or explode and spawn further icebergs. The final stage of an iceberg’s life is especially volatile and difficult to predict. Scientists struggle to precisely foresee the path an iceberg might follow since the shape and size of an iceberg, ocean currents, winds, and waves affect a berg’s velocity. In Iceberg Alley, the average drift speed is about 0.5 mph, though some bergs zip along at more than 2 mph. At this point in their lives, Arctic icebergs are prone to capsizing since increased erosion over time results in a loss of stability. In an iceberg’s death throes, as some glaciologists describe it, the blocks are also noisy. Icebergs groan and sputter as they break up over open water. Glaciologists talk about “singing” icebergs, too. When bergs scrape the seabed or rub against each other they can vibrate and emit chilling harmonic tremors, like running a finger around the rim of a wine glass. Perhaps it is to be expected that we talk about icebergs like they are alive. Iceberg cowboys try to capture these creatures as they migrate through Iceberg Alley, before they die and all that unspoiled freshwater mixes with the ocean.

Ed Kean is a fifth-generation fisherman known abroad as “Captain Ahab of the Ice.” To my ears, his speech sounds like the mix of a cheery Irishman and a grunting whaler too busy or too weary to open his mouth any wider. Despite Kean’s easygoing attitude, he is acutely aware of the danger posed by icebergs that float in the waters off the coast of Newfoundland. Many calved from the very same glacier, Sermeq Kujalleq, that produced the frozen torpedo that sank the Titanic just 320 nautical miles away. But the risk is worth it to continue living off the sea. As the iceberg cowboy tells it, his family used to harvest ice from icebergs to cool fish that they brought up to the plants in Labrador. In the 1970s they had the ice tested at Memorial University of Newfoundland to ensure it was safe. In the process, they learned that it was exceptionally pure. In the 1990s Kean began harvesting ice commercially, and he has been at it ever since.

Icebergs “taste like water should taste,” he explains. That’s why they are worth wrangling. According to Kean, he and his wife drink several liters of iceberg water a day and his mother “will only drink iceberg water.” In St. John’s, when I tell people I’m interested in iceberg harvesting, they almost instantly reference Ed Kean, who is something of a celebrity here. The global COVID-19 pandemic spoiled my plan to sail with Kean, so I chat with him about icebergs while we’re both standing on solid land. Proudly, the fisherman also directs me to videos online that document his work. By all accounts, it is arduous labor. Some years, Kean sells more than 1 million liters of the specialty water.

On days he harvests icebergs, which is almost every day in the short migration season, Kean is awake by dawn with a small crew. Using a satellite map, Kean identifies icebergs and motors his large fishing boat toward them. Once he sees the ice, he can select his approach. If the berg is grounded and sufficiently stable, he can carefully maneuver his accompanying barge, outfitted with a crane, near the ice. Then, using a hydraulic clamp attachment, he and his crew scoop up the ice and feed it into a large grinder on the ship. The ice is shredded and piped into storage tanks.

More commonly, the iceberg cowboy cannot get so close to the ice and harvesting looks a lot more like battling a wild animal. Because the ice can flip and roll unpredictably, Kean must approach cautiously. Plus, icebergs have treacherous underwater projections or “legs” Kean names them, that could damage his ship. Occasionally, his first move is to whip out a rifle. He shoots icebergs in hopes of splintering off a chunk. “Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t.” Kean tells me that he is moving away from firearms now, though. The crew next leaves the big rusty rig behind and hops into a small motorboat to come near the ice. They circle the iceberg looking for smaller pieces that have broken off. Even these chunks can weigh more than a ton.

The frozen surface is not a static island, but an enormous, peripatetic rock-hard reef.

The next part comes right out of a rodeo. The cowboys use long wooden poles tipped with metal hooks to prod and jostle the ice closer to the boat. Once the iceberg is well positioned, the men fling a net over the ice and wrap it tight. The brute is then dragged back to the vessel, where a crane is lowered to affix a hook to the net. The ice is winched aboard and dropped onto the deck. The ice is rinsed, and now the backbreaking work begins. Using axes, the crew hacks into the ice, chipping it into smaller chunks. These are then shoveled into 1,000-liter plastic storage containers where they will melt. Kean says he has difficulty maintaining a crew for many seasons since the work is so difficult. Maybe I should be grateful that I don’t have to participate in this rodeo.

Since I don’t get the opportunity to play cowboy in St. John’s, I decide to be a tourist instead. I board a ship from St. John’s Port Authority to see an iceberg. If harvesting icebergs is like herding cattle, sightseeing for icebergs is itself a bit like being on safari. My tour operator even describes “hunting” for icebergs on the open sea. Our target is dangerous and unpredictable, capable of lashing out at any moment. For that reason, the provincial government of Newfoundland and Labrador has published viewing guidelines. We should keep a distance equal to the length of an iceberg or twice its height, whichever is greater. Anything within this perimeter is considered the “danger zone,” in which viewers are exposed to falling ice, large waves, and submerged hazards.

As with lions and leopards, it can also be hard to tell where or when our mark might appear. “Who knows what nature is going to give us,” my guide explains. Luckily, I get to see icebergs. The first we encounter rises out of the ocean like a smooth boulder. A cotillion of terns is settled at the peak of the dome’s gentle curves, and for a moment, the ice seems passive and gentle. Then a wave crashes into the mass and I am reminded that the frozen surface is not a static island, but an enormous, peripatetic rock-hard reef. As the boat inches closer, I can see the slippery surface continue below the waves, stretching into the dark ocean. I am transported by the alien sight up close. The floating orb is like a puffy white flying saucer cutting through the water.

The next iceberg we spy is more spectacular, sparkling like a crystal castle in the bright sun. Two pinnacles, like turret-adored towers, loom 50 feet over our ship. They are connected with a low ice wall that reminds me of a crenelated parapet. I ask one of the guides if she thinks we can sail nearer. “That’s up to the captain,” she answers, “but he probably won’t get closer because this berg isn’t grounded.” Salt water lashes the ice from every angle, like the ocean is a great artist carving a magnificent sculpture from a giant block. The ice dwarfs our boat even from our safe distance. When I finally look down, I am mesmerized by the aquamarine hue radiating from the submarine foundation. Intellectually, I know that around 90 percent of an iceberg’s mass is hidden. But there is so much ice bobbing on the waves, I cannot fathom the true size of this creature.

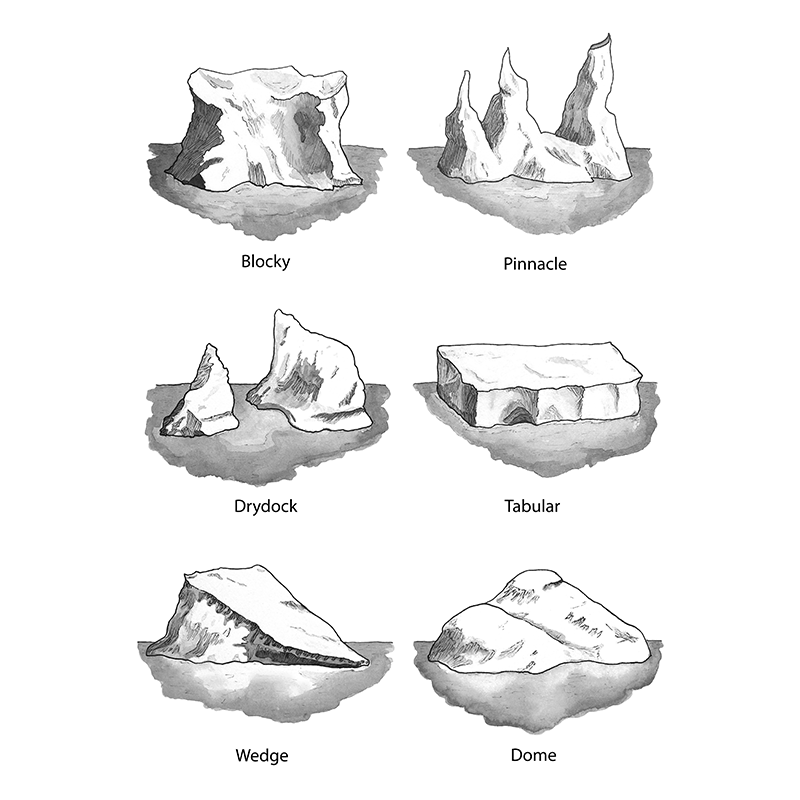

Technically, I’ve seen a domed and a pinnacled iceberg. Glaciologists distinguish between six different types. The categories are helpful because different shaped bergs have greater or lesser height-to-drift ratios and drift speed as a percentage of wind speed. Some varieties are also more attractive for harvesting, depending on whom you ask. Domed icebergs are smooth and rounded on top. A blocky iceberg has a mostly flat top and steep vertical sides. Like the name implies, wedge icebergs have one thick end that tapers to a thin edge that disappears beneath the water. Pinnacled icebergs can be shaped like pyramids or consist of several spires that soar above the bulk of the mass. Similarly, dry-dock icebergs have two points like a giant letter U, the base of which is at water level so a boat could float on top of the berg between the towers. Lastly, a tabular iceberg has a flat surface because it usually calves from an ice sheet or shelf glacier. Most come from Antarctica, though some originate from Greenland and the ice caps of Arctic islands. These bergs can be many kilometers in length and width—far greater than the powerful ice I witness in Newfoundland.

Back on land, I head to raucous George Street to be “screeched-in.” The cheeky local tradition begins with a supplication. I introduce myself and say I’d like to be a Newfoundlander. Next, I am meant to recite a vow. It is impenetrable to my daft ears, so I mumble along and jump to the next step, taking a shot of rum. It goes down easier than the final act: kissing a cod. I am again grateful the pandemic has changed my plans, since I get to peck the fish through a mask. I smooch the frozen cod and quickly order an Iceberg beer. Brewed up the street at Quidi Vidi Brewery, the smooth lager advertises itself as being “made with pure 20,000-year-old iceberg water.” The beer is refreshing, but I cannot notice anything special about it. Admittedly, I am no connoisseur, and I’ve just had a fish in my face.

While I drink the beer, I think of Ed Kean. His sobriquet, Captain Ahab of the Ice, is unfitting. At the end of Moby-Dick,

Herman Melville’s fictional captain is drowned in his monomaniacal

attempt to subdue the white whale. In St. John’s, the lager in my hand

is a sign of Kean’s success. He has vanquished icebergs and lived to

tell about it. ![]()

Matthew Birkhold is an associate professor in the department of Germanic languages and literatures at The Ohio State University, and the author of Chasing Icebergs: How Frozen Freshwater Can Save the Planet. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, Foreign Affairs, The Washington Post, The Paris Review, and Indian Country Today.

Excerpted from Chasing Icebergs: How Frozen Freshwater Can Save the Planet by Matthew Birkhold. Published by Pegasus Books, 2023 .

Lead image: Bparsons98 / Shutterstock

No comments:

Post a Comment