Originally yesterday I looked this up to see if I was spelling this river right and I wasn't. I was trying to spell it Willamet or Wilamet. But, you can see the correct spelling below. We visited Lake Oswego, a suburb of Portland south of there that is also on the Willamette River also. As you can see the Willamette River also travels north through the City of Portland on it's way to the Columbia River. I think it said that 12 to 14 % of the Columbia River is water from the Willamette River. I saw many speedboats and fast fishing boats traveling up and down the Willamette River past Lake Oswego as I visited there yesterday at a beautiful park with a trail and even docking facilities there along the river.

begin quote from:

Willamette River - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willamette_River

The Willamette River

is a major tributary of the Columbia River, accounting for 12 to 15

percent of the Columbia's flow. The Willamette's main stem is 187

miles ...

Johnson Creek (Willamette River) - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johnson_Creek_(Willamette_River)

Willamette River

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Willamette River | |

|

The Willamette passing through Downtown Portland in a photo from the 1980s

|

|

| Name origin: From a Clackamas Native American village name[1] | |

| Country | United States |

|---|---|

| State | Oregon |

| Tributaries | |

| - left | Coast Fork Willamette River, Long Tom River, Marys River, Luckiamute River, Yamhill River, Tualatin River |

| - right | Middle Fork Willamette River, McKenzie River, Calapooia River, Santiam River, Molalla River, Clackamas River |

| Cities | Eugene, OR, Corvallis, OR, Albany, OR, Salem, OR, Newberg, OR, Wilsonville, OR, Portland, OR |

| Source | Confluence of Middle Fork Willamette River and Coast Fork Willamette River |

| - location | near Eugene, Lane County, Oregon |

| - elevation | 438 ft (134 m) [2] |

| - coordinates | 44°01′23″N 123°01′25″W [2] |

| Mouth | Columbia River |

| - location | Portland, Multnomah County, Oregon |

| - elevation | 10 ft (3 m) [2] |

| - coordinates | 45°39′10″N 122°45′53″WCoordinates: 45°39′10″N 122°45′53″W [2] |

| Length | 187 mi (301 km) [3] |

| Basin | 11,478 sq mi (29,730 km2) [4] |

| Discharge | for Morrison Bridge, Portland, 12.8 miles (20.6 km) from mouth [n 1] |

| - average | 33,010 cu ft/s (900 m3/s) |

| - max | 420,000 cu ft/s (11,900 m3/s) |

| - min | 4,200 cu ft/s (100 m3/s) |

|

A map of the Willamette River, its drainage basin, major tributaries and major cities

|

|

| Wikimedia Commons: Willamette River | |

Originally created by plate tectonics about 35 million years ago and subsequently altered by volcanism and erosion, the river's drainage basin was significantly modified by the Missoula Floods at the end of the most recent ice age. Humans began living in the watershed over 10,000 years ago. There were once many tribal villages along the lower river and in the area around its mouth on the Columbia. Indigenous peoples lived throughout the upper reaches of the basin as well.

Rich with sediments deposited by flooding and fed by prolific rainfall on the western side of the Cascades, the Willamette Valley is one of the most fertile agricultural regions in North America, and was thus the destination of many 19th-century pioneers traveling west along the Oregon Trail. The river was an important transportation route in the 19th century, although Willamette Falls, just upstream from Portland, was a major barrier to boat traffic. In the 21st century, major highways follow the river, and roads cross it on more than 50 bridges.

Since 1900, more than 15 large dams and many smaller ones have been built in the Willamette's drainage basin, and 13 of them are operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). The dams are used primarily to produce hydroelectricity, to maintain reservoirs for recreation, and to prevent flooding. The river and its tributaries support 60 fish species, including many species of salmon and trout; this is despite the dams, other alterations, and pollution (especially on the river's lower reaches). Part of the Willamette Floodplain was established as a National Natural Landmark in 1987 and the river was named as one of 14 American Heritage Rivers in 1998.

Contents

Course

Ocean-going cargo ship anchored at the mouth of the Willamette

Proposals have been made for deepening the Multnomah Channel to 43 feet (13 m) in conjunction with roughly 103.5 miles (166.6 km) of tandem-maintained navigation on the Columbia River.[11] Between the 1850s and the 1960s, channel-straightening and flood control projects, as well as agricultural and urban encroachment, cut the length of the river between the McKenzie River confluence and Harrisburg by 65 percent. Similarly, the river was shortened by 40 percent in the stretch between Harrisburg and Albany.[12]

The Multnomah Channel from the Sauvie Island Bridge

Beginning at 438 feet (134 m) above sea level, the main stem descends 428 feet (130 m) between source and mouth, or about 2.3 feet per mile (0.4 m per km).[2] The gradient is slightly steeper from the source to Albany than it is from Albany to Oregon City.[13] At Willamette Falls, between West Linn and Oregon City, the river plunges about 40 feet (12 m).[13] For the rest of its course, the river is extremely low-gradient and is affected by Pacific Ocean tidal effects from the Columbia.[13] The main stem of the Willamette varies in width from about 330 to 660 feet (100 to 200 m).[13]

Discharge

With an average flow at the mouth of about 37,400 cubic feet per second (1,060 m3/s), the Willamette ranks 19th in volume among rivers in the United States[14] and contributes 12 to 15 percent of the total flow of the Columbia River.[15] The Willamette's flow varies considerably season to season, averaging about 8,200 cubic feet per second (230 m3/s) in August to more than 79,000 cubic feet per second (2,200 m3/s) in December.[13]

The Willamette River at Harrisburg

The river below Willamette Falls, 26.5 miles (42.6 km) from the mouth, is affected by semidiurnal tides,[16] and gauges have detected reverse flows (backwards river flows) upstream from Ross Island at RM 15 (RK 24).[17] The National Weather Service issues tide forecasts for the river at the Morrison Bridge.[18]

Geology

The Willamette River basin was created primarily by plate tectonics and volcanism and was altered by erosion and sedimentation, including some related to enormous glacial floods as recent as 13,000 years ago.[19] The initial trough-like configuration was created about 35 million years ago[15] as a forearc basin while the Pacific Plate subducted beneath the North American Plate.[19] Marine deposits on top of older volcanics underlie the valley, which was initially part of the continental shelf, rather than a separate inland sea.[20] About 20 to 16 million years ago, uplift formed the Coast Range and separated the basin from the Pacific Ocean.[19]Basalts of the Columbia River Basalt Group, from eruptions in eastern Oregon, flowed across large parts of the northern half of the basin about 15 million years ago.[19] They covered the Tualatin Mountains (West Hills), most of the Tualatin Valley, and the slopes of hills further south, with up to 1,000 feet (300 m) of lava.[21] Later depositions covered the basalt with up to 1,000 feet (300 m) of silt in the Portland and Tualatin basins.[22] During the Pleistocene, beginning roughly 2.5 million years ago, volcanic activity in the Cascades combined with a cool, moist climate to produce further heavy sedimentation across the basin; braided rivers created alluvial fans spreading down from the east.[19]

The glacial Bellevue Erratic at Erratic Rock State Natural Site. The rock was transported to the Willamette Valley by the Missoula Floods.[23]

The northern part of the watershed is underlain by a network of faults capable of producing earthquakes at any time, and many small quakes have been recorded in the basin since the mid-19th century.[26] In 1993, the Scotts Mills earthquake—the largest recent earthquake in the valley, measuring 5.6 on the Richter scale—was centered near Scotts Mills, about 34 miles (55 km) south of Portland.[27] It caused $30 million in damage, including harm to the Oregon State Capitol in Salem.[28] Evidence suggests that massive quakes of 8 or more on the Richter scale have occurred historically in the Cascadia subduction zone off the Oregon coast, most recently in 1700 CE, and that others as strong as 9 on the Richter scale occur every 500 to 800 years.[29] The basin's high population density, its nearness to this subduction zone, and its loose soils, which tend to amplify shaking, make the Willamette Valley especially vulnerable to damage from strong earthquakes.[26]

Watershed

Willamette Valley map showing main stem and major tributaries

About 2.5 million people lived in the Willamette River basin as of 2010, about 65 percent of the population of Oregon.[31] As of 2009, the basin contained 20 of the 25 most populous cities in Oregon.[7][32] These cities include Springfield, Eugene, Corvallis, Albany, Salem, Keizer, Newberg, Oregon City, West Linn, Milwaukie, Lake Oswego, and Portland.[7][32] The largest is Portland, with more than 500,000 residents.[32] Not all of these cities draw water directly from the Willamette for their municipal water supply.[33][34] Other cities in the watershed (but not on the main-stem river) with populations of 20,000 or more are Gresham, Hillsboro, Beaverton, Tigard, McMinnville, Tualatin, Woodburn, and Forest Grove.[7][32]

Sixty-four percent of the watershed is privately owned, while 36 percent is publicly owned.[35] The U.S. Forest Service manages 30 percent of the watershed, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management 5 percent, and the State of Oregon 1 percent.[35] Sixty-eight percent of the watershed is forested; agriculture, concentrated in the Willamette Valley, makes up 19 percent, and urban areas cover 5 percent.[35] More than 81,000 miles (130,000 km) of roads criss-cross the watershed.[35]

In 1987, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior designated 713 acres (289 ha) of the watershed in Benton County as a National Natural Landmark. This area is the Willamette Floodplain, the largest remaining unplowed native grassland in the North Pacific geologic province, which encompasses most of the Pacific Northwest coast.[36]

History

First inhabitants

The Willamette River near the confluence with the Molalla River

A boulder at Alton Baker Park in Eugene engraved with the Kalapuyan "Whilamut" "Where the river ripples and runs fast"

The indigenous peoples of the Willamette River practiced a variety of life ways. Those on the lower river, slightly closer to the coast, often relied on fishing as their primary economic mainstay. Salmon was the most important fish to Willamette River tribes as well as to the Native Americans of the Columbia River, where white traders traded fish with the Native Americans. Upper-river tribes caught steelhead and salmon, often by building weirs across tributary streams. Tribes of the northern Willamette Valley practiced a generally settled lifestyle. The Chinooks lived in great wooden lodges,[44] practiced slavery, and had a well-defined caste system.[44] People of the south were more nomadic, traveling from place to place with the seasons. They were known for the controlled burning of woodlands to create meadows for hunting and plant gathering (especially camas).[45]

Fur trade

The Willamette River first appears in the records of outsiders in 1792, when it was seen by British Lieutenant William Robert Broughton of the Vancouver Expedition, led by George Vancouver.[46] From the 18th to the mid-19th century, much of the Pacific Northwest and most of its rivers were involved in the fur trade, in which fur trappers (mostly French-Canadians working for the Hudson's Bay Company and the North West Company, which later merged) hunted for beaver and sea otter on rivers, streams, and coastlines. The pelts of these animals commanded substantial prices in either the United States, Canada or eastern Asia, because of their "thick, luxurious and water-repellent" qualities.[47]Fur traders heavily exploited the Willamette River and its tributaries.[48] During this period, the Siskiyou Trail (or California-Oregon Trail) was created. This trading path, over 600 miles (970 km) long, stretched from the mouth of the Willamette River near present-day Portland south through the Willamette Valley, crossing the Cascades and the Siskiyou Mountains, and south through the Sacramento Valley to San Francisco.[49]

19th-century development

In 1805, the Lewis and Clark Expedition traveled thousands of miles across central North America in an attempt to map and explore the Louisiana Territory of the United States and the Oregon Country, which were then occupied mainly by Native Americans and settlers from Great Britain. As the expedition traveled down and back up the Columbia River, it missed the mouth of the Willamette, one of the Columbia's largest tributaries. It was only after receiving directions from natives along the Sandy River that the explorers learned about their oversight. William Clark returned down the Columbia and entered the Willamette River in April 1806.[15] The United States Exploring Expedition passed through the Willamette Valley in 1841 while traveling along the Siskiyou Trail. The expedition members noted extensive salmon fishing by natives at Willamette Falls, much like that at Celilo Falls on the Columbia River.[50]In the middle part of the 19th century, the Willamette Valley's fertile soils, pleasant climate, and abundant water attracted thousands of settlers from the eastern United States, mainly the Upland South borderlands of Missouri, Iowa, and the Ohio Valley.[51] Many of these emigrants followed the Oregon Trail, a 2,170-mile (3,490 km) trail across western North America that began at Independence, Missouri, and ended at various locations near the mouth of the Willamette River. Although people had been traveling to Oregon since 1836, large-scale migration did not begin until 1843, when nearly 1,000 pioneers headed westward. Over the next 25 years, some 500,000 settlers traveled the Oregon Trail, braving the rapids of the Snake and Columbia Rivers to reach the Willamette Valley.[52][53][54]

Oregon City circa 1867, with Willamette Falls in the background

After Portland was incorporated in 1851, quickly growing into Oregon's largest city, Oregon City gradually lost its importance as the economic and political center of the Willamette Valley. Beginning in the 1850s, steamboats began to ply the Willamette, despite the fact that they could not pass Willamette Falls.[59] As a result, navigation on the Willamette River was divided into two stretches: the 27-mile (43 km) lower stretch from Portland to Oregon City—which allowed connection with the rest of the Columbia River system—and the upper reach, which encompassed most of the Willamette's length.[60] Any boats whose owners found it absolutely necessary to get past the falls had to be portaged. This led to competition for business among steam portage companies.[61][62] In 1873, the construction of the Willamette Falls Locks bypassed the falls and allowed easy navigation between the upper and lower river. Each lock chamber measured 210 feet (64 m) long and 40 feet (12 m) wide, and the canal was originally operated manually before it switched to electrical power.[62] Today, the lock system is little used.[63]

As commerce and industry flourished on the lower river, most of the original settlers acquired farms in the upper Willamette Valley. By the late 1850s, farmers had begun to grow crops on most of the available fertile land.[64] The settlers increasingly encroached on Native American lands. Skirmishes between natives and settlers in the Umpqua and Rogue valleys to the southwest of the Willamette River led the Oregon state government to remove the natives by military force.[65] They were first led off their traditional lands to the Willamette Valley, but soon were marched to the Coast Indian Reservation. In 1855, Joel Palmer, an Oregon legislator, negotiated a treaty with the Willamette Valley tribes, who, although unhappy with the treaty, ceded their lands to non-natives.[66][67] The natives were then relocated by the government to a part of the Coast Reservation that later became the Grande Ronde Reservation.[67]

Between 1879 and 1885, the Willamette River was charted by Cleveland S. Rockwell, a topographical engineer and cartographer for the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey. Rockwell surveyed the lower Willamette from the foot of Ross Island through Portland to the Columbia River and then downstream on the Columbia to Bachelor Island.[68] Rockwell's survey was extremely detailed, including 17,782 hydrographic soundings. His work helped open the port of Portland to commerce.[69]

In the second half of the 19th century, the USACE dredged channels and built locks and levees in the Willamette's watershed. Although products such as lumber were often transported on an existing network of railroads in Oregon, these advances in navigation helped businesses deliver more goods to Portland, feeding the city's growing economy. Trade goods from the Columbia basin north of Portland could also be transported southward on the Willamette due to the deeper channels made at the Willamette's mouth.[70]

20th and 21st centuries

Conveyor belt loading debris onto a barge as part of the Big Pipe Project

With development in and near the river came increased pollution. By the late 1930s, efforts to stem the pollution led to formation of a state sanitary board to oversee modest cleanup efforts.[4] In the 1960s, Oregon Governor Tom McCall led a push for stronger pollution controls on the Willamette.[73] In this, he was encouraged by Robert (Bob) Straub—the state treasurer and future Oregon governor (1975)—who first proposed a Willamette Greenway program during his 1966 gubernatorial campaign against McCall.[74] The Oregon State Legislature established the program in 1967. Through it, state and local governments cooperated in creating or improving a system of parks, trails, and wildlife refuges along the river.[46] In 1998, the Willamette became one of 14 rivers designated an American Heritage River by former U.S. President Bill Clinton.[75] By 2007 the Greenway had grown to include more than 170 separate land parcels, including 10 state parks.[46] Public uses of the river and land along its shores include camping, swimming, fishing, boating, hiking, bicycling, and wildlife viewing.[46]

In 2008, government agencies and the non-profit Willamette Riverkeeper organization designated the full length of the river as the Willamette River Water Trail.[76] Four years later, the National Park Service added the Willamette water trail—expanded to 217 miles (349 km) to include some of the major tributaries—to its list of national water trails.[77] The water-trail system is meant to protect and restore waterways in the United States and to enhance recreation on and near them.[78]

A 1991 agreement between the City of Portland and the State of Oregon to dramatically reduce combined sewer overflows (CSOs)[79] led to Portland's Big Pipe Project. The project, part of a related series of Portland CSO projects completed in late 2011 at a cost of $1.44 billion,[80] separates the city's sanitary sewer lines from storm-water inputs that sometimes overwhelmed the combined system during heavy rains. When that occurred, some of the raw sewage in the system flowed into the river instead of into the city's wastewater treatment plant. The Big Pipe project and related work reduces CSO volume on the lower river by about 94 percent.[81][82]

In June 2014, Dean Hall became the first person to swim the entire length of the Willamette River.[83][84] He swam 184 miles (296 km) from Eugene to the river mouth in 25 days.[84]

Dams and bridges

Dams

The weir-type dam at Willamette Falls

The only dam on the Willamette's main stem is the Willamette Falls Dam, a low weir-type structure at Willamette Falls that diverts water into the headraces of the adjacent mills and a power plant.[85] The locks at Willamette Falls were completed in 1873. Elsewhere on the main stem, numerous minor flow-regulation structures force the river into a narrower and deeper channel to facilitate navigation and flood control.[46]

The dams on the Willamette's major tributaries are primarily large flood-control, water storage, and power-generating dams. Thirteen of these dams were built from the 1940s through the 1960s to be operated by the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE),[86][87] and 11 of those produce hydropower.[86] Flood-control dams operated by the USACE are estimated to hold up to 27 percent of the Willamette's runoff. They are used to regulate river flows so as to cut peaks off floods and increase low flows in late summer and autumn, and to divert water into deeper, narrower channels to prevent flooding.[46][71][85][88][89] In addition, a relatively small of amount of the water stored in the reservoirs is used for irrigation.[90]

Detroit Dam, the basin's second tallest

A continuing controversy about these high dams involves Chinook salmon and steelhead blocked from roughly half of their historic habitat and spawning grounds on the Willamette's major tributaries. Unable to survive and reproduce as they once did, they have been "brought to the brink of extinction".[92] Endangered species listings and a subsequent lawsuit by environmental groups led to a recovery plan approved in 2008.[93] Since then, work has proceeded slowly, and the Corps, citing engineering difficulties and cost, may not meet the original agreed-upon deadline of 2023 for a system of effective remedies.[92]

Other major dams in the Willamette watershed are owned by other interests; for example, several hydroelectric facilities on the Clackamas River are owned by Portland General Electric. They include the River Mill Hydroelectric Project, the Oak Grove project, and the dam at Timothy Lake.[94]

Bridges

The Hawthorne Bridge is the oldest remaining highway structure over the Willamette.

The Ross Island Bridge carries U.S. Route 26 (Mount Hood Highway) over the river at RM 14 (RK 23). It is one of 10 highway bridges crossing the river in Portland. The 3,700-foot (1,100 m) bridge is the only cantilevered deck truss in Oregon.[99][100]

The lower deck of the Steel Bridge can be raised independently of the upper deck.

Further downstream is the oldest remaining highway structure over the Willamette, the Hawthorne Bridge, built in 1910.[104] It is the oldest vertical-lift bridge in operation in the United States[105] and the oldest highway bridge in Portland. It is also the busiest bicycle and transit bridge in Oregon, with over 8,000 cyclists[106] and 800 TriMet buses (carrying about 17,400 riders) daily.[105]

The St. Johns Bridge in northwest Portland

The Broadway Bridge, slightly downstream of the Steel Bridge, was the world's longest double-leaf bascule drawbridge at the time of its construction in 1913.[109] Further downstream, the St. Johns Bridge, a steel suspension bridge built in 1931, replaced the last of the Willamette River ferries in Portland.[110] At about RM 6 (RK 10), it carries U.S. Route 30 Bypass.[111] The bridge has two Gothic towers supporting the span.[112] The adjacent park and neighborhood of Cathedral Park are named after the Gothic Cathedral-like appearance of the bridge towers. It is the tallest bridge in Portland, with 408 ft (122 m) tall towers and a 205 ft (62 m) navigational clearance.[113]

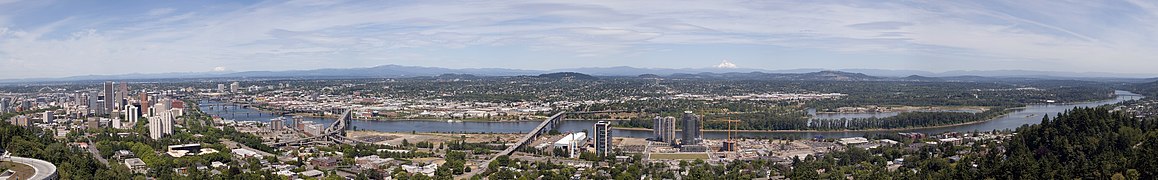

The Willamette as it passes through Portland. The bridges seen, from

left to right, are the Fremont, Steel, Burnside, Morrision, Hawthorne,

Marquam, Ross Island and Sellwood. The Tilikum Crossing bridge was not

built at the time of this 2007 photo.

Flooding

An aerial view of the 1996 flooding

In the summer of 1866, the Willamette was measured at 21 feet (6.4 m) above the "low water mark," and there were more flooding worries. Upstream on the Columbia River, water was also high and the city of The Dalles was nearly flooded.[117]

Flooding returned in the winter of early 1890, when the river first rose very quickly and then fell very quickly.[118][119] Portland's main street was completely submerged, communication over the Cascades was cut off, and many rail lines were forced to shut down.[119] In 1894, another major flood occurred on the Willamette, and although it too caused huge damage, it was not as large as that of 1861.[6]

The remains of Vanport City in June 1948

Although the Willamette was, by mid-century, heavily engineered and controlled by a complex system of dams, channels, and barriers, it experienced severe floods through the end of the century. Storms caused a major flood that swelled the Willamette and other rivers in the Pacific Northwest from December 1964 through January 1965, submerging nearly 153,000 acres (620 km2) of land.[127] Before dawn on December 21, 1964, the Willamette reached 29.4 feet (9.0 m), which was higher than the Portland seawall. By this time, about 15 people had died as a result of the flooding and about 8,000 Oregonians had been forced to evacuate their homes in search of other shelter.[128]

On December 24, President Lyndon B. Johnson ordered federal aid for the flooded areas. Meanwhile, the Willamette continued to rise.[129] In the next couple of days, the river receded, but on December 27, it was at 29.8 feet (9.1 m), which was still nearly 12 feet (3.7 m) above the flood stage.[130] The Willamette continued to pose flooding threats through January 1965,[131] and more stormy weather occurred along the Pacific Coast.[132]

| “ | The river crested at one town after another—at Corvallis 3½ feet above flood stage, Oregon City 18 feet above, Portland 10.5 feet above—much like a meal moving through a boa constrictor. | ” |

| — Associated Press journalist, February 10, 1996, [133] | ||

About 450 concrete flood-protection walls in Portland that had been constructed during the February flood, each weighing about 5,500 pounds (2,500 kg), were removed in April.[136] In October, they were replaced by a larger steel wall that cost the city about $300,000. The new wall had 0.25-inch (6.4 mm) removable steel plates designed to better prevent future flooding.[137]

Pollution

The Tom McCall Waterfront Park is named after an Oregon governor who led a cleanup of the river.

A 1927 City Club of Portland report labeled the waterway "filthy and ugly", and identified the City of Portland as the worst offender. The Oregon Anti-Stream Pollution League brought a pollution-abatement measure before the 39th Oregon Legislative Assembly in 1937. The bill passed, but Governor Charles Martin vetoed it. The Izaak Walton League and the Oregon affiliate of the National Wildlife Federation countered the governor's veto with a ballot initiative, which passed in November 1938.[4]

Shortly after he was elected in 1966, Governor Tom McCall ordered water quality tests on the Willamette, conducted his own research on the water quality, and became head of the Oregon State Sanitary Authority. McCall learned that the river was heavily polluted in Portland. In a television documentary, Pollution in Paradise, he said that "the Willamette River was actually cleaner when the Oregon Sanitary Authority was created in 1938 than it was in 1962."[73] He then discouraged tourism in the state and made it harder for companies to qualify for a permit to operate near the river. He also regulated how much those companies could pollute and closed plants that did not meet state pollution standards.[138][139]

Despite earlier cleanup efforts, state studies in the 1990s identified a wide variety of pollutants in the river bottom, including heavy metals, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and pesticides along the lower 12 miles (19 km) of the river, in Portland.[140] As a result, this section of the river was designated a Superfund site in 2000,[141] involving the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in cleanup of the river bottom.[142] The initial cleanup is focused on the portion between Swan Island and Sauvie Island.[143] Pollution is exacerbated by combined sewer overflows, which the city has greatly reduced through its Big Pipe Project.[144] Further upstream, the pressing environmental issues have mainly been variations in pH and dissolved oxygen.[145] The Willamette is nevertheless clean enough to be used by cities such as Corvallis and Wilsonville for drinking water.[146]

Since pollution concerns are primarily along the lower river, the Willamette in general scores relatively high on the Oregon Water Quality Index (OWQI), which is compiled by the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ). The DEQ considers index scores of less than 60 to be very poor; the other categories are 60–79 (poor); 80–84 (fair); 85–89 (good), and 90–100 (excellent).[147] The Willamette River's water quality is rated excellent near the source, though it gradually declines to fair near the mouth. Between 1998 and 2007, the average score for the upper Willamette at Springfield (RM 185, RK 298) was 93. At Salem (RM 84, RK 135), the score was 89, and good scores continued all the way to the Hawthorne Bridge in Portland (RM 13, RK 21) at 85. Scores were in the "fair" category further downstream; the least favorable reading was at the Swan Island Channel midpoint (RM 0.5, RK 0.8) at 81. By comparison, sites on the Winchuck River, the Clackamas, and the North Santiam all scored 95, and a site at a pump station on Klamath Strait Drain between Upper Klamath Lake and Lower Klamath Lake recorded the lowest score in Oregon at 19.[148]

Flora and fauna

Osprey are among bird species often seen along the Willamette River.

Fish in the Willamette basin include 31 native species, among them cutthroat, bull, and rainbow trout, several species of salmon, sucker, minnow, sculpin, and lamprey, as well as sturgeon, stickleback, and others. Among the 29 non-native species in the basin, there are brook, brown, and lake trout, largemouth and smallmouth bass, walleye, carp, bluegill, and others. In addition to fish, the basin supports 18 species of amphibians, such as the Pacific giant salamander. Beaver and river otter are among 69 mammal species living in the watershed, also frequented by 154 bird species, such as the American dipper, osprey, and harlequin duck. Garter snakes are among the 15 species of reptiles found in the basin.[150]

Species diversity is greatest along the lower river and its tributaries. Threatened, endangered, or sensitive species include spring Chinook salmon, winter steelhead, chum salmon, Coho salmon and Oregon chub.[150] In the central valley, several projects have been done to restore and protect wetlands[151] in order to provide habitat for bald eagles, Fender's blue butterfly (of which 6,000 remain), Oregon chub, Bradshaw's desert parsley, a variety of Willamette fleabane, and Kincaid's lupine.[152][153][154] In the early 21st century, osprey populations are increasing along the river, possibly because of a ban on the pesticide DDT and on the birds' ability to use power poles for nesting.[155] Beaver populations, presumed to be much lower than historic levels, are increasing throughout the basin.[155]

See also

- List of crossings of the Willamette River

- List of longest streams of Oregon

- List of rivers of Oregon

- Steamboats of the Willamette River

Notes

References

- Benke, et al., p. 621

Works cited

- — "Oregon Water Quality Index Summary Report, Water Years 1998–2007" (PDF), May 2008. Oregon Department of Environmental Quality. Retrieved April 10, 2011.

- Benke, Arthur C., ed., and Cushing, Colbert E., ed.; Stanford, Jack A.; Gregory, Stanley V.; Hauer, Richard F.; Snyder, Eric B. (2005). "Chapter 13: Columbia River Basin" in Rivers of North America. Burlington, Massachusetts: Elsevier Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-088253-1. OCLC 59003378.

- Bright, William (2004). Native American Placenames of the United States. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3576-X. OCLC 53019644.

- Campbell, Lyle (1997). American Indian Languages. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1. OCLC 247389024.

- Deur, Douglas; Turner, Nancy J. (2005). Keeping it Living: Traditions of Plant Use and Cultivation on the Northwest Coast of North America. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-7748-1267-2. OCLC 57316620.

- Edwards, G. Thomas; Schwantes, Carlos A. (1986). Experiences in a Promised Land: Essays in Pacific Northwest History. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-96328-X. OCLC 12805717.

- Engeman, Richard H. (2009). The Oregon Companion: A Historical Gazetteer of the Useful, the Curious, and the Arcane. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 0-88192-899-2. OCLC 236142647.

- Gulick, Bill (2004). Steamboats on Northwest Rivers. Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Press. ISBN 0-87004-438-9. OCLC 53000219.

- Holman, Frederick Van Voorhies (1907). Dr. John McLoughlin, the Father of Oregon. Cleveland, Ohio: A. H. Clark Company. ISBN 1-131-13770-1. OCLC 365933029.

- Laenen, Antonius; Dunnette, David A. (1997). River Quality: Dynamics and Restoration. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. ISBN 1-56670-138-4. OCLC 34885999.

- Loy, Willam G.; Allan, Stuart Allan; Buckley, Aileen R.; Meecham, James E. (2001) [1976]. Atlas of Oregon (2nd ed.). Eugene, Oregon: University of Oregon Press. ISBN 0-87114-101-9. OCLC 228223337.

- Mackie, Richard Somerset (1997). Trading Beyond the Mountains: the British Fur Trade on the Pacific, 1793–1843. Vancouver: UBC Press. ISBN 0-7748-0613-3. OCLC 82135549.

- McArthur, Lewis A.; McArthur, Lewis L. (2003) [1928]. Oregon Geographic Names (7th ed.). Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87595-277-1. OCLC 53075956.

- Meinig, D.W. (1998). The Shaping of America: A Geographical Perspective on 500 Years of History, Volume 3: Transcontinental America, 1850–1915. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08290-8. OCLC 60197763.

- Orr, Elizabeth L.; Orr, William N. (1999). Geology of Oregon (5th ed.). Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. ISBN 0-7872-6608-6. OCLC 42944922.

- Ruby, Robert H.; Brown, John A. (1976). The Chinook Indians: Traders of the Lower Columbia River. Civilization of the American Indian. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2107-6. OCLC 1958350.

- Samson, Karl (2010). Frommer's Oregon. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-470-53771-X. OCLC 671277501.

- Smith, Dwight A.; Norman, James B.; Dykman, Pieter T. (1989) [1986]. Historic Highway Bridges of Oregon (2nd ed.). Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87595-205-4. OCLC 20362124.

- Snipp, C. Matthew (1989). American Indians: The First of This Land. New York, New York: Russell Sage Foundation. ISBN 0-87154-822-4. OCLC 19670797.

- Stenzel, Franz (1972). Cleveland Rockwell: Scientist and Artist, 1837–1907. Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society. ISBN 0-87595-037-X. OCLC 333762.

- Thornton, Russell (1990). American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History Since 1492. Civilization of the American Indian. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2220-X. OCLC 263150623.

- Timmen, Fritz (1973). Blow for the Landing. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer. OCLC 38286714.

- U.S. Coast & Geodetic Survey (1887). Report of the Superintendent of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey Showing the Progress of the Work during the Fiscal Year Ending with June 1886. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. OCLC 28937852.

- Wilkes, Charles (1845). Narrative of the United States' Exploring Expedition, During the Years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842: Condensed and abridged. London: Whittaker and Co. OCLC 602918838.

- Williams, Travis (2009). The Willamette River Field Guide. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 0-88192-866-6. OCLC 243601804.

- Wortman, Sharon Wood; Wortman, Ed.; Norman, James B. (2006). The Portland Bridge Book (3rd ed.). Portland, Oregon: Urban Adventure Press. ISBN 0-9787365-1-6. OCLC 76928209.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Willamette River. |

- City of Portland River Renaissance Strategy

- Guiding the Willamette [web archive], Think Out Loud radio program on Oregon Public Broadcasting, April 1, 2009

- Historic river channels between Albany and Monmouth – Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries lidar poster

- Portland Harbor DEQ cleanup – Oregon State Department of Environmental Quality

- Willamette Riverkeeper – Non-profit environmental organization

Categories:

- Willamette River

- American Heritage Rivers

- Ferries of Oregon

- Rivers of Benton County, Oregon

- Rivers of Clackamas County, Oregon

- Rivers of Lane County, Oregon

- Rivers of Linn County, Oregon

- Rivers of Marion County, Oregon

- Rivers of Multnomah County, Oregon

- Rivers of Washington County, Oregon

- Rivers of Yamhill County, Oregon

- Rivers of Columbia County, Oregon

- Rivers of Oregon

- Tributaries of the Columbia River

- Willamette Valley

No comments:

Post a Comment